Zois Report 6/2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanian Political Science Review Vol. XXI, No. 1 2021

Romanian Political Science Review vol. XXI, no. 1 2021 The end of the Cold War, and the extinction of communism both as an ideology and a practice of government, not only have made possible an unparalleled experiment in building a democratic order in Central and Eastern Europe, but have opened up a most extraordinary intellectual opportunity: to understand, compare and eventually appraise what had previously been neither understandable nor comparable. Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review was established in the realization that the problems and concerns of both new and old democracies are beginning to converge. The journal fosters the work of the first generations of Romanian political scientists permeated by a sense of critical engagement with European and American intellectual and political traditions that inspired and explained the modern notions of democracy, pluralism, political liberty, individual freedom, and civil rights. Believing that ideas do matter, the Editors share a common commitment as intellectuals and scholars to try to shed light on the major political problems facing Romania, a country that has recently undergone unprecedented political and social changes. They think of Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review as a challenge and a mandate to be involved in scholarly issues of fundamental importance, related not only to the democratization of Romanian polity and politics, to the “great transformation” that is taking place in Central and Eastern Europe, but also to the make-over of the assumptions and prospects of their discipline. They hope to be joined in by those scholars in other countries who feel that the demise of communism calls for a new political science able to reassess the very foundations of democratic ideals and procedures. -

Belarus – the Unfulfilled Phenomena: the Prospects of Social Mobilization

14 Jovita Pranevičiūtė* Institute of International Relations and Political Science, University of Vilnius Belarus – the Unfulfilled Phenomena: The Prospects of Social Mobilization For more than ten years Belarus has be under authoritarian rule and it has been difficult to explain this phenomenon. The rhetoric of the Belarusian elites – governing and oppositional – is analyzed as the main tool of the struggle to mobilize society for collec- tive action in the political fight. The rhetoric of the ruling elite, and also the opposition, is analyzed in three dimensions: how competing elites are talking about the glorious past; the degraded present; and the utopian future. Through collective action, the nation will reverse the conditions that have caused its present degradation and recover its original harmonious essence. The main aim of this study is to demonstrate that in short - and perhaps even in the medium-run - the Belarusian president Alexander Lukahenko will remain in power due to the successful employment of the trinomial rhetorical structure. The conclusions can be shocking meaning that the ruling elite has been able to persuade society that the glorious past has been realized in the times of Soviet Union and at the moment Belarus is living in the conditions of utopian future, i.e. future is a reality, nonetheless the short period of the opposition ruin rule in the nineties and negative actions of opposition in nowadays. While the utopian reality is based at least on the ideas of economical survival and believes that all the aims of society have been reached already, the opposition has no chance to mobilize a critical part of society to ensure the support to its own ideas and to get in to power. -

Russian Federation State Actors of Protection

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Russian Federation State Actors of Protection March 2017 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Russian Federation State Actors of Protection March 2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Free phone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Print ISBN 978-92-9494-372-9 doi: 10.2847/502403 BZ-04-17-273-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9494-373-6 doi: 10.2847/265043 BZ-04-17-273-EN-C © European Asylum Support Office 2017 Cover photo credit: JessAerons – Istockphoto.com Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO Country of Origin Report: Russian Federation – State Actors of Protection — 3 Acknowledgments EASO would like to acknowledge the following national COI units and asylum and migration departments as the co-authors of this report: Belgium, Cedoca (Center for Documentation and Research), Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons Poland, Country of Origin Information Unit, Department for Refugee Procedures, Office for Foreigners Sweden, Lifos, Centre for Country of Origin Information and Analysis, Swedish Migration Agency Norway, Landinfo, Country of -

Яюm I C R O S O F T W O R

Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS 2004 ANNUAL REPORT Minsk 2005 C O N T E N T S INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW /2 STATISTICAL BACKGROUND /3 CHANGES IN THE LEGISLATION /5 INFRINGEMENTS OF RIGHTS OF MASS-MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS, CONFLICTS IN THE SPHERE OF MASS-MEDIA Criminal cases for publications in mass-media /13 Encroachments on journalists and media /16 Termination or suspension of mass-media by authorities /21 Detentions of journalists, summoning journalists to law enforcement bodies. Warnings of the Office of Public Prosecutor /29 Censorship. Interference in professional independence of editions /35 Infringements related to access to information (refusals in granting information, restrictive use of institute of accreditation) /40 The conflicts related to reception and dissemination of foreign information or activity of foreign mass-media /47 Economic policy in the sphere of mass-media /53 Restriction of the right on founding mass-media /57 Interference with production of mass-media /59 Hindrance to distribution of mass-media production /62 SENSATIONAL CASES The most significant litigations with participation of mass-media and journalists /70 Dmitry Zavadsky's case /79 Belarusian periodic printed editions mentioned in the monitoring /81 1 INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW The year 2004 for Belarus was the year of parliamentary elections and the referendum. As usual during significant political campaigns, the pressure on mass-media has increased in 2004. The deterioration of the media situation was not a temporary deviation after which everything usually comes back to normal, but represented strengthening of systematic and regular pressure upon mass- media, which continued after the election campaign. -

Policing in Federal States

NEPAL STEPSTONES PROJECTS Policing in Federal States Philipp Fluri and Marlene Urscheler (Eds.) Policing in Federal States Edited by Philipp Fluri and Marlene Urscheler Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) www.dcaf.ch The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces is one of the world’s leading institutions in the areas of security sector reform (SSR) and security sector governance (SSG). DCAF provides in-country advisory support and practical assis- tance programmes, develops and promotes appropriate democratic norms at the international and national levels, advocates good practices and makes policy recommendations to ensure effective democratic governance of the security sector. DCAF’s partners include governments, parliaments, civil society, international organisations and the range of security sector actors such as police, judiciary, intelligence agencies, border security ser- vices and the military. 2011 Policing in Federal States Edited by Philipp Fluri and Marlene Urscheler Geneva, 2011 Philipp Fluri and Marlene Urscheler, eds., Policing in Federal States, Nepal Stepstones Projects Series # 2 (Geneva: Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces, 2011). Nepal Stepstones Projects Series no. 2 © Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces, 2011 Executive publisher: Procon Ltd., <www.procon.bg> Cover design: Angel Nedelchev ISBN 978-92-9222-149-2 PREFACE In this book we will be looking at specimens of federative police or- ganisations. As can be expected, the federative organisation of such states as Germany, Switzerland, the USA, India and Russia will be reflected in their police organisation, though the extremely decentralised approach of Switzerland with hardly any central man- agement structures can hardly serve as a paradigm of ‘the’ federal police organisation. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

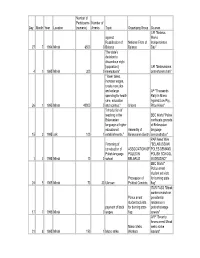

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Download Book

84 823 65 Special thanks to the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies for assistance in getting access to archival data. The author also expresses sincere thanks to the International Consortium "EuroBelarus" and the Belarusian Association of Journalists for information support in preparing this book. Photos by ByMedia.Net and from family albums. Aliaksandr Tamkovich Contemporary History in Faces / Aliaksandr Tamkovich. — 2014. — ... pages. The book contains political essays about people who are well known in Belarus and abroad and who had the most direct relevance to the contemporary history of Belarus over the last 15 to 20 years. The author not only recalls some biographical data but also analyses the role of each of them in the development of Belarus. And there is another very important point. The articles collected in this book were written at different times, so today some changes can be introduced to dates, facts and opinions but the author did not do this INTENTIONALLY. People are not less interested in what we thought yesterday than in what we think today. Information and Op-Ed Publication 84 823 © Aliaksandr Tamkovich, 2014 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE Probably, it is already known to many of those who talked to the author "on tape" but I will reiterate this idea. I have two encyclopedias on my bookshelves. One was published before 1995 when many people were not in the position yet to take their place in the contemporary history of Belarus. The other one was made recently. The fi rst book was very modest and the second book was printed on classy coated paper and richly decorated with photos. -

Gibbs Umd 0117E 12639.Pdf

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LEGITIMACY, TERRORIST ATTACKS AND POLICE Jennifer Catherine Gibbs Doctor of Philosophy, 2011 Directed By: Professor Laura Dugan Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice Scholars often suggest that terrorism – “the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence to attain a political, economic, religious or social goal through fear, coercion or intimidation” (LaFree & Dugan, 2007, 184) – is a battle of legitimacy. As the most ubiquitous representatives of the government’s coercive force, the police should be most susceptible to terrorism stemming from perceptions of illegitimacy. Police are attractive symbolic and strategic targets, and they were victimized in over 12% of terrorist attacks worldwide since 1970. However, empirical research assessing the influence of legitimacy on terrorist attacks, generally, and scholarly attention to terrorist attacks on police are scant. The purpose of this dissertation is to examine the influence of state and police legitimacy and alternative explanations on the proportion of all and only fatal terrorist attacks on police in 82 countries between 1999 and 2008. Data were drawn from several sources, including the Global Terrorism Database and the World Values Survey. Surprisingly, results of Tobit analyses indicate that police legitimacy, measured by the percentage of the population who have at least some confidence in police, is not significantly related to the proportion of all terrorist attacks on police or the proportion of fatal terrorist attacks on police. State legitimacy was measured by four indicators; only the percentage of the population who would never protest reached significance, lending limited support for this hypothesis. Greater societal schism, the presence of a foreign military and greater economic inequality were consistently significant predictors of higher proportions of terrorist attacks on police. -

Fr Fr Communication Aux Membres

Parlement européen 2019-2024 Commission des affaires étrangères Commission du développement Sous-commission «Droits de l’homme» 23.9.2020 COMMUNICATION AUX MEMBRES Objet: PRIX SAKHAROV POUR LA LIBERTÉ DE L’ESPRIT 2020 Les députés trouveront en annexe la liste (alphabétique) des candidats au prix Sakharov pour la liberté de l’esprit 2020, lesquels, conformément au statut du prix Sakharov, ont été proposés par au moins quarante députés au Parlement européen ou par un groupe politique, ainsi que les justifications et les biographies reçues par l’unité «Actions droits de l’homme». DIRECTION GÉNÉRALE DES POLITIQUES EXTERNES DE L’UNION CM\1213925FR.docx PE658.278v02-00 FR Unie dans la diversité FR PRIX SAKHAROV POUR LA LIBERTÉ DE L’ESPRIT 2020 Candidats, classés par ordre alphabétique, proposés par des groupes politiques et des députés à titre individuel Candidat Activité Proposé par Les militants LGBTI polonais Jakub Gawron, Paulina Pajak et Paweł Preneta ont créé l’«Atlas de la haine», un projet recensant les nombreuses municipalités polonaises qui ont adopté, rejeté ou qui examinent des «résolutions anti-LGBTI». Kamil Maczuga a joué un rôle important en suivant les débats sur cette question au sein des gouvernements 4 militants LGBTI – locaux et en diffusant des informations aux Malin Björk, Terry Jakub Gawron, Paulina militants, aux médias et aux responsables Reintke, Marc 1 Pajak, Paweł Preneta et Angel, Rasmus politiques en Pologne et au-delà. Au Kamil Maczuga, Andresen et Pologne printemps 2020, Jakub Gawron, Paulina Pajak 39 autres députés and Paweł Preneta ont été poursuivis en justice par cinq des gouvernements locaux qui avaient adopté de telles déclarations. -

Review–Chronicle

REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 Human Rights Center Viasna ReviewChronicle » of the Human Rights Violations in Belarus in 2005 VIASNA « Human Rights Center Minsk 2006 1 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 » VIASNA « Human Rights Center 2 Human Rights Center Viasna, 2006 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 INTRODUCTION: main trends and generalizations The year of 2005 was marked by a considerable aggravation of the general situation in the field of human rights in Belarus. It was not only political rights » that were violated but social, economic and cultural rights as well. These viola- tions are constant and conditioned by the authoritys voluntary policy, with Lu- kashenka at its head. At the same time, human rights violations are not merely VIASNA a side-effect of the authoritarian state control; they are deliberately used as a « means of eradicating political opponents and creating an atmosphere of intimi- dation in the society. The negative dynamics is characterized by the growth of the number of victims of human rights violations and discrimination. Under these circums- tances, with a high level of latent violations and concealed facts, with great obstacles to human rights activity and overall fear in the society, the growth points to drastic stiffening of the regimes methods. Apart from the growing number of registered violations, one should men- Human Rights Center tion the increase of their new forms, caused in most cases by the development of the state oppressive machine, the expansion of legal restrictions and ad- ministrative control over social life and individuals. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). -

En En Motion for a Resolution

European Parliament 2019-2024 Plenary sitting B9-0274/2020 14.9.2020 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION to wind up the debate on the statement by the Vice-President of the Commission / High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy pursuant to Rule 132(2) of the Rules of Procedure on the situation in Belarus (2020/2779(RSP)) Kati Piri, Tonino Picula, Norbert Neuser, Robert Biedroń on behalf of the S&D Group RE\1213222EN.docx PE655.465v01-00 EN United in diversityEN B9-0274/2020 European Parliament resolution on the situation in Belarus (2020/2779(RSP)) The European Parliament, – having regard to its previous resolutions on Belarus, in particular those of 4 October 2018 on the deterioration of media freedom1, of 19 April 2018 on Belarus following the local elections of 18 February 20182, of 24 November 2016 on the situation in Belarus following the parliamentary elections of 11 September 20163 and of 8 October 2015 on the death penalty in Belarus4, – having regard to the Conclusions by the President of the European Council following the video conference of the members of the European Council of 19 August 2020, – having regard to the declarations by the High Representative on behalf of the European Union of 11 August 2020 on the presidential elections and of 11 September 2020 on the escalation of violence and intimidation against members of the Coordination Council, – having regard to the statements by the High Representative/Vice-President, in particular those of 7 August 2020 ahead of the presidential elections and of 14