United Nations Working Group On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News from Copenhagen

News from Copenhagen Number 423 Current Information from the OSCE PA International Secretariat 29 February 2012 Prisons, economic crisis and arms control focus of Winter Meeting The panel of the General Committee on Democracy, Human The panel of the General Committee on Economic Affairs, Rights and Humanitarian Questions on 23 February. Science, Technology and Environment on 23 February. The 11th Winter Meeting of the OSCE Parliamentary the vice-chairs on developments related to the 2011 Belgrade Assembly opened on 23 February in Vienna with a meeting Declaration. of the PA’s General Committee on Democracy, Human Rights The Standing Committee of Heads of Delegations met on and Humanitarian Questions, in which former UN Special 24 February to hear reports of recent OSCE PA activities, as Rapporteur on Torture Manfred Nowak took part, along with well as discuss upcoming meetings and election observation. Bill Browder, Eugenia Tymoshenko, and Iryna Bogdanova. After a discussion of the 4 March presidential election in Committee Chair Matteo Mecacci (Italy) noted the impor- Russia, President Efthymiou decided to deploy a small OSCE tance of highlighting individual stories to “drive home the PA delegation to observe. urgency of human rights.” In this regard, Browder spoke Treasurer Roberto Battelli presented to the Standing Com- about the case of his former attorney, the late Sergei Magnit- mittee the audited accounts of the Assembly for the past finan- sky, who died in pre-trial detention in Russia. cial year. The report of the Assembly’s outside independent Eugenia Tymoshenko discussed the case of her mother, professional auditor has given a positive assessment on the former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, cur- PA´s financial management and the audit once again did not rently serving a seven-year prison sentence. -

The Belarusian Association of Journalists

1 THE BELARUSIAN ASSOCIATION OF JOURNALISTS Info-posting No. 7-10 February 22 – March 28, 2010 March 2010 appeared to be as difficult for Belarusian journalistic community as the preceding months. Firstly, the Supreme Court of Belarus declined an appeal of Belarusian Association of Journalists against an official warning to the BAJ, issued by the Ministry of Justice of Belarus. "To charge a journalists' association with illegally issuing press cards is absurd and a blatant attack on freedom of association for journalists," said Aidan White, IFJ General Secretary. "It is clear that the government is putting legal shackles on the BAJ in response to its uncompromising campaign for media freedom and journalists' rights," he added. Secondly, the month was full of KGB and police searches and interrogations as well as other tools of pressure, applied in relation to journalists on behalf of law- enforcement agencies. Siarzhuk Sierabro, the Editor of “People’s News of Vitsiebsk” Web-site was interrogated again by police on February 22, 2010. The interrogation concerned a criminal case, filed against a civil activist Siarhei Kavalenka, who had placed a white-red-white national banner on the central Christmas tree in Vitsiebsk on January 7, 2010. Among other, a legal investigator of police department at Vitsiebsk Regional Executive Committee Andrei Baranau was interested if S. Sierabro had been aware of the civil protest action and if he had prepared beforehand for taking pictures of this event. Alaksandr Dzianisau, an independent journalist from Hrodna was accused of ‘self-will’ (article 23.39 of Belarusian Law on Administrative Torts) by police on February 23, 2010. -

March 15, 2013 Brussels Forum Belarus: a Forgotten Story Rush

March 15, 2013 Brussels Forum Belarus: A Forgotten Story Rush transcript. Check against video. Mr. Ivan Vejvoda: Thank you very much. I hope everyone had a good lunch. The offerings were very rich. We do not have a Siesta time at Brussels Forum yet. We do have the child care, maybe we’ll think of Siesta for next year. My name is Ivan Vejvoda. I’m the Vice President for programs at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, and I will, in the span of two, three minutes, describe a very significant part of the German Marshall Fund activities in terms of support to democracy in civil society. The German Marshall Fund celebrated 40 years of its existence last year and for the past 20 years, since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the historical changes that happened in Europe, we have been engaged in a series of activities to support democracy in civil 1 society throughout the post-communist world beginning with a central and east European trust for civil society that we partook in with five other private foundations. There was work in the Carpasian region and GMF saw itself as a pioneer in these activities along with other governmental and nongovernmental donors. The fund pioneered a new model in 2003. Ten years ago, a private public partnership with strong local buy in and that was the Balkan Trust for Democracy, which I had the honor of leading for eight years and it is being led by Gordana Delic, who’s in the room here, and that became a truly transatlantic private public partnership. -

In Belarus, the Leopard Flaunts His Spots1

11 In Belarus, the leopard flaunts his spots1 Even before the polls closed in Belarus’s presidential election on 19 December, supporters of opposition candidates were planning their protests. Although the conduct of the campaign was remarkably liberal by recent standards, opponents of Alexander Lukashenka’s regime confidently expected another rorted result, so no one was surprised when, late on polling day, the president claimed an implausibly huge victory. His return to authoritarian form was dramatically displayed when the government’s security forces beat up protesters rallying in the centre of the national capital, Minsk. At least 640 people were arrested, including seven of the nine opposition candidates. The leading opposition candidate, Vladimir Neklyayev, was seized and bashed on his way to the demonstration, suffering severe concussion. He was taken to hospital, where a group of plain-clothes thugs burst into the ward, dragging him off to jail. Neklyayev, who has serious vascular problems, has been denied treatment and there are fears for his life. Another leading opposition candidate, Andrei Sannikov, also injured, was stopped by traffic police and pulled out of a car on his way to hospital. His wife tried to hold on to him, for which she was also assaulted. Beatings in jail are reported to be widespread, and some protesters have been forced to recant, Iranian-style, on television. 1 First published in Inside Story, 4 Jan. 2011, insidestory.org.au/in-belarus-the-leopard- flaunts-his-spots. 167 A DIffICUlT NEIGHBoURHooD Just over a week later, in Moscow, came the conviction of Russian oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky and a fellow Yukos Oil executive for allegedly stealing and laundering the proceeds of most of the oil produced by their own company. -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Яюm I C R O S O F T W O R

Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS 2004 ANNUAL REPORT Minsk 2005 C O N T E N T S INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW /2 STATISTICAL BACKGROUND /3 CHANGES IN THE LEGISLATION /5 INFRINGEMENTS OF RIGHTS OF MASS-MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS, CONFLICTS IN THE SPHERE OF MASS-MEDIA Criminal cases for publications in mass-media /13 Encroachments on journalists and media /16 Termination or suspension of mass-media by authorities /21 Detentions of journalists, summoning journalists to law enforcement bodies. Warnings of the Office of Public Prosecutor /29 Censorship. Interference in professional independence of editions /35 Infringements related to access to information (refusals in granting information, restrictive use of institute of accreditation) /40 The conflicts related to reception and dissemination of foreign information or activity of foreign mass-media /47 Economic policy in the sphere of mass-media /53 Restriction of the right on founding mass-media /57 Interference with production of mass-media /59 Hindrance to distribution of mass-media production /62 SENSATIONAL CASES The most significant litigations with participation of mass-media and journalists /70 Dmitry Zavadsky's case /79 Belarusian periodic printed editions mentioned in the monitoring /81 1 INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW The year 2004 for Belarus was the year of parliamentary elections and the referendum. As usual during significant political campaigns, the pressure on mass-media has increased in 2004. The deterioration of the media situation was not a temporary deviation after which everything usually comes back to normal, but represented strengthening of systematic and regular pressure upon mass- media, which continued after the election campaign. -

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN the LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist Degree, Belarusian State University

SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES by Olga Klimova Specialist degree, Belarusian State University, 2001 Master of Arts, Brock University, 2005 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Olga Klimova It was defended on May 06, 2013 and approved by David J. Birnbaum, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Lucy Fischer, Distinguished Professor, Department of English, University of Pittsburgh Vladimir Padunov, Associate Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh Aleksandr Prokhorov, Associate Professor, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, College of William and Mary, Virginia Dissertation Advisor: Nancy Condee, Professor, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright © by Olga Klimova 2013 iii SOVIET YOUTH FILMS UNDER BREZHNEV: WATCHING BETWEEN THE LINES Olga Klimova, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The central argument of my dissertation emerges from the idea that genre cinema, exemplified by youth films, became a safe outlet for Soviet filmmakers’ creative energy during the period of so-called “developed socialism.” A growing interest in youth culture and cinema at the time was ignited by a need to express dissatisfaction with the political and social order in the country under the condition of intensified censorship. I analyze different visual and narrative strategies developed by the directors of youth cinema during the Brezhnev period as mechanisms for circumventing ideological control over cultural production. -

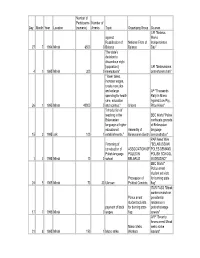

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Download Book

84 823 65 Special thanks to the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies for assistance in getting access to archival data. The author also expresses sincere thanks to the International Consortium "EuroBelarus" and the Belarusian Association of Journalists for information support in preparing this book. Photos by ByMedia.Net and from family albums. Aliaksandr Tamkovich Contemporary History in Faces / Aliaksandr Tamkovich. — 2014. — ... pages. The book contains political essays about people who are well known in Belarus and abroad and who had the most direct relevance to the contemporary history of Belarus over the last 15 to 20 years. The author not only recalls some biographical data but also analyses the role of each of them in the development of Belarus. And there is another very important point. The articles collected in this book were written at different times, so today some changes can be introduced to dates, facts and opinions but the author did not do this INTENTIONALLY. People are not less interested in what we thought yesterday than in what we think today. Information and Op-Ed Publication 84 823 © Aliaksandr Tamkovich, 2014 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE Probably, it is already known to many of those who talked to the author "on tape" but I will reiterate this idea. I have two encyclopedias on my bookshelves. One was published before 1995 when many people were not in the position yet to take their place in the contemporary history of Belarus. The other one was made recently. The fi rst book was very modest and the second book was printed on classy coated paper and richly decorated with photos. -

THE BELARUSIAN ASSOCIATION of JOURNALISTS Mass Media Week

THE BELARUSIAN ASSOCIATION OF JOURNALISTS Mass Media Week in Belarus Info‐posting February 18 – March 3, 2013 Within the reporting period there were several cases of denied information, one official warning for contributing to foreign mass media unaccredited, a detention of three journalists “by mistake”. Also the expectations to get back the Belarus Press Photos 2011 did not fulfill; and communication with state structures failed about possible changes in the present‐day mass media law. On February 18 the journalist Iryna Khalip who had been formally allowed to visit Britain and Russia until April 3 came to the police station for a regular call‐in, as required by the sentence. However, instead of the head of the probation inspection Natallia Kaliada, she met Aliaksandr Kupchenya, the head of the probation unit of the Minsk city police department. According to Mrs. Khalip, the police official inquired when she would leave Belarus. When the journalist answered that she did not know the date, Mr. Kupchenya turned angry. “We have opened up the border for you! You didn't believe we'd do that, but we have, so that you go away and never come back. Listen to me, don't come back. Take your child, fly to Britain, obtain political asylum, but don't come back. You're not needed here, all you do is distort facts," these were his words. We remind that on February 13 Iryna Khalip was allowed to go temporarily to Great Britain and to Russia: to see her husband and the editorial office of Novaya Gazeta. On February 19 Iryna Khalip filed a complaint to the Interior Minister Ihar Shunevich demanding an in‐ house probe against Mr. -

The Nunn-Lugar Program Should Be Increased, Not

Hryshchenko, Nurgaliev, & Sannikov olitical leaders and public opinion in Belarus, term partner, and could cause serious delays in the final Kazakhstan, and Ukraine are concerned that the elimination of nuclear weapons that have not yet been U.S. Congress seems inclined to reduce funding dismantled. Pfor the Cooperative Threat Reduction or Nunn-Lugar The Nunn-Lugar program has become a vital factor program, which originated in the U.S. Senate in 1991 in the fulfillment by our three governments of our obli- and later became a part of gations under the the budget of the U.S. De- START I Treaty, which partment of Defense. In of course has an impor- our view, reduction of this VIEWPOINT: tant impact on the na- program would not serve tional security of the the interests of interna- THE NUNN-LUGAR United States. U.S. as- tional security, nor would sistance under the it serve the national secu- PROGRAM SHOULD Nunn-Lugar program rity interests of the United made it possible for us States. BE INCREASED, to liquidate nuclear We believe it is fair to weapons and strengthen say that recent, major suc- NOT REDUCED nonproliferation re- cesses in the field of non- by Kostyantyn Hryshchenko, Bulat Nurgaliev & gimes. In particular, proliferation, including Andrei Sannikov American assistance is the May 1995 decision of being utilized in the Non-Proliferation Belarus, Kazakhstan, Treaty Review and Extension Conference in New York and Ukraine to remove warheads from strategic deliv- City to extend the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in- ery systems for eventual dismantlement in Russia, to definitely, were to a considerable extent facilitated by the destroy fixed and mobile launchers, to create and per- adoption and implementation of the Nunn-Lugar pro- fect export control systems, to inventory and safeguard gram. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA).