Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonyukuk and Turkic State Ideology “Mangilik

THE TONYUKUK AND AN ANCIENT TURK’S STATE IDEOLOGY OF “MANGILIK EL” PJAEE, 17 (6) (2020) THE TONYUKUK AND AN ANCIENT TURK’S STATE IDEOLOGY OF “MANGILIK EL” Nurtas B. SMAGULOV, PhD student of the of the Department of Kazakhstan History, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Kazakhstan, [email protected] Aray K. ZHUNDIBAYEVA, PhD, Head of the Department of Kazakh literature, accociate professor of the Department of Kazakh literature, Shakarim state University of Semey (SSUS), (State University named after Shakarim of city Semey), Kazakhstan, [email protected] Satay M. SIZDIKOV, Doctor of historical science, professor of the Department of Turkology, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Kazakhstan, [email protected] Arap S. YESPENBETOV, Doctor of philological science, professor of the Department of Kazakh literature, Shakarim state University of Semey (SSUS), (State University named after Shakarim of city Semey), Kazakhstan, [email protected] Ardak K. KAPYSHEV, Candidate of historical science, accociate professor of the Department of International Relations, History and Social Work, Abay Myrzkhmetov Kokshetau University, Kazakhstan, [email protected] Nurtas B. SMAGULOV, Aray K. ZHUNDIBAYEVA, Satay M. SIZDIKOV, Arap S. YESPENBETOV, Ardak K. KAPYSHEV: The Tonyukuk And An Ancient Turk’s State Ideology Of “Mangilik El” -- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(6). ISSN 1567-214x ABSTRACT Purpose of the study. Studying and evaluating the activities of Tonykuk, who was the state adviser to the Second Turkic Kaganate, the main ideologist responsible for the ideological activities of the Kaganate from 682 to 745, is an urgent problem of historical science. In the years 646-725 he worked as an adviser on political and cultural issues of the three Kagan. -

TURKIC POLITICAL HISTORY Early Postclassical (Pre-Islamic) Period

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE Richard Dietrich, Ph.D. TURKIC POLITICAL HISTORY Early Postclassical (Pre-Islamic) Period Contents Part I : Overview Part II : Government Part III : Military OVERVIEW The First Türk Empire (552-630) The earliest mention of the Türks is found in 6th century Chinese sources in reference to the establishment of the first Türk empire. In Chinese sources they are called T’u-chüeh (突厥, pinyin Tūjué, and probably pronounced tʰuot-küot in Middle Chinese), but refer to themselves in the 7th - 8th century Orkhon inscriptions written in Old Turkic as Türük (��ఇ఼�� ) or Kök Türük (�� �ఇ �� :�� �ఇ �఼ �� ). In 552 the Türks emerged as a political power on the eastern steppe when, under the leadership of Bumin (T’u-men in the Chinese sources) from the Ashina clan of the Gök Türks, they revolted against and overthrew the Juan-juan Empire (pinyin Róurán) that had been the most significant power in that region for the previous century and a half. After defeating the Juan-juan and taking their territories, Bumin took the title of kaghan, supreme leader, while his brother Istemi (also Istämi or Ishtemi, r. 552-576) became the yabghu, a title indicating his subordinate status. Bumin was the senior leader, ruling the eastern territories of the empire, while Istemi ruled the western territories. Bumin died in 553, was briefly followed by his son followed by his son Kuo-lo (Qara?), and then by another of his sons, Muhan (or Muqan, r. 553-572). In the following decades Istemi and Muhan extended their rule over the Kitan in Manchuria, the Kirghiz tribes in the Yenisei region, and destroyed the Hephthalite Empire in a joint effort with the Sasanians. -

Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV

BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 Sponsored by VELIYEV RUSTAM SALEH oglu T ranslated by ZAHID MAHAMMAD oglu AHMADOV Edited by FARHAD MAHAMMAD oglu MUSTAFAYEV Budagov B.A. Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia. - Baku “Elm”, 1997, -1 7 4 p. ISBN 5-8066-0757-7 The geographical toponyms preserved in the immense territories of Turkic nations are considered in this work. The author speaks about the parallels, twins of Azerbaijani toponyms distributed in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Altay, the Ural, Western Si beria, Armenia, Iran, Turkey, the Crimea, Chinese Turkistan, etc. Be sides, the geographical names concerned to other Turkic language nations are elucidated in this book. 4602000000-533 В ------------------------- 655(07)-97 © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 A NOTED SCIENTIST Budag Abdulali oglu Budagov was bom in 1928 at the village o f Chobankere, Zangibasar district (now Masis), Armenia. He graduated from the Yerevan Pedagogical School in 1947, the Azerbaijan State Pedagogical Institute (Baku) in 1951. In 1955 he was awarded his candidate and in 1967 doctor’s degree. In 1976 he was elected the corresponding-member and in 1989 full-member o f the Azerbaijan Academy o f Sciences. Budag Abdulali oglu is the author o f more than 500 scientific articles and 30 books. Researches on a number o f problems o f the geographical science such as geomorphology, toponymies, history o f geography, school geography, conservation o f nature, ecology have been carried out by academician B.A.Budagov. He makes a valuable contribution for popularization o f science. -

TURKIC HISTORY from the Huns to the Ottoman Empire

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE TURKIC HISTORY From the Huns to the Ottoman Empire The course is an overview of Turkic history roughly from the 1st century BC to the 20th century, a period which covers about two thousand years of the history of the Turks. The course covers the topics from the emergence of the Turks in Central Asian theatre to the end of the Ottoman Empire. The Turks first emerged in the northeast of present Mongolia in the steps between the Orkhon and Selenga rivers. They most possibly moved from Siberian taiga sometimes within the first millenium BC to these areas, and reached to the Lake Balkash steps and northern Tien Shan region in 300 AD. The oldest, and the holiest term in the Turkic languages, Tengri, which means both sky and transcendent religious power, appears in Chinese texts in the third century. Though the Chinese religious texts mentions Tengri as far back as the 3rd century BC, the first Turkic speaking people had their place in history in the 4th century in the area surrounded with Tien Shan, Siberia and Mongolia. The contents of the course are as follows: 1. The Turkic World: Geography, Culture and Language 2. The Hsiung-nu and the Hun Empires 3. The Turkish Empire 4. Uyghur and Khazar Khanates 5. Conversion of the Turks to Islam 6. The Muslim Turkish States: The Ghaznevids and Karahanids 7. The Great Seljuk Empire 8. The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum (Anatolia) 9. The Rise of the Ottoman Power in Western Anatolia and the Byzantine Challenge 10. Tamerlane and the Last Turkic Empire of the Silk Road 11. -

Old Turkic Script

Old Turkic script The Old Turkic script (also known as variously Göktürk script, Orkhon script, Orkhon-Yenisey script, Turkic runes) is the Old Turkic script alphabet used by the Göktürks and other early Turkic khanates Type Alphabet during the 8th to 10th centuries to record the Old Turkic language.[1] Languages Old Turkic The script is named after the Orkhon Valley in Mongolia where early Time 6th to 10th centuries 8th-century inscriptions were discovered in an 1889 expedition by period [2] Nikolai Yadrintsev. These Orkhon inscriptions were published by Parent Proto-Sinaitic(?) Vasily Radlov and deciphered by the Danish philologist Vilhelm systems Thomsen in 1893.[3] Phoenician This writing system was later used within the Uyghur Khaganate. Aramaic Additionally, a Yenisei variant is known from 9th-century Yenisei Syriac Kirghiz inscriptions, and it has likely cousins in the Talas Valley of Turkestan and the Old Hungarian alphabet of the 10th century. Sogdian or Words were usually written from right to left. Kharosthi (disputed) Contents Old Turkic script Origins Child Old Hungarian Corpus systems Table of characters Direction Right-to-left Vowels ISO 15924 Orkh, 175 Consonants Unicode Old Turkic Variants alias Unicode Unicode U+10C00–U+10C4F range See also (https://www.unicode. org/charts/PDF/U10C Notes 00.pdf) References External links Origins According to some sources, Orkhon script is derived from variants of the Aramaic alphabet,[4][5][6] in particular via the Pahlavi and Sogdian alphabets of Persia,[7][8] or possibly via Kharosthi used to write Sanskrit (cf. the inscription at Issyk kurgan). Vilhelm Thomsen (1893) connected the script to the reports of Chinese account (Records of the Grand Historian, vol. -

The Decipherment of the Turkish Runic Inscriptions and Its Effects on Turkology in East and West

THE DECIPHERMENT OF THE TURKISH RUNIC INSCRIPTIONS AND ITS EFFECTS ON TURKOLOGY IN EAST AND WEST Wolfgang-E. SCHARLIPP Introduction The term “Runes” for the letters of the Old Turkish alphabet, used mainly for inscriptions but also a few manuscripts, has lately been criticized by some Turkish scientists for its misleading meaning. As “Runes” is originally the term of the old Germanic alphabet, this term could suggest a Germanic origin of the Turkish alphabet. Indeed the term indicates nothing more than a similarity of shape that these alphabets have in common, which has also created the term “runiform” letters. As such nationalist hair-splitting does not contribute to scientific discussion, we will in the following use the term “Turkish runes” with a good conscience. This contribution aims at showing similarities and differences between the ways that research into this alphabet and the texts written in it, went among Turkish scientists on the one side and Non-Turkish scientists on the other side. We will also see how these differences came into existence. In order to have a sound basis for our investigation we will first deal with the question how the Turkish runes were deciphered. We will then see how the research into the inscriptions continued among Western scholars, before we finally come to the effects that this research had on scientists in Turkey, or to be more precise, in the Ottoman Empire and then in the Republic of Turkey. In the 19th century Several expeditions were sent out in order to collect material concerning the stone inscriptions in Central Asia. -

Journal of Eurasian Studies Volume VI., Issue 2. / April — June 2014

April-June 2014 JOURNAL OF EURASIAN STUDIES Volume VI., Issue 2. _____________________________________________________________________________________ ARDEN-WONG, Lyndon Tang Governance and Administration in the Turkic Period The period between 630-682 is seen as a period of Tang governance on the Mongolian Plateau. The Chinese architectural influence during this period has been well known to scholars of Turkic memorial complex archaeology. Historical documents (both Chinese and runic) attest to the employment of Chinese artisans and architects to construct the memorial complexes of the 2nd Eastern Türk Khaganate (683-742),1 which are well-known in the archaeological record.2 It is also reckoned that no settlements have been discovered dating from the Turkic period which makes the Uighur architectural developments that followed seem even bolder. However, archaeologically and architecturally, this period is rather unclear. With new archaeological data available, it is worth exploring this phenomenon more closely. This paper will contextualise the historical backdrop, then begin an expository study of the architectural evidence from this period. It is argued that this period indeed does have an architectural legacy and that it set models of elite architecture of the steppe, which were particularly relevant to the 2nd Eastern Türk and the Eastern Uighur Khaganate (744-840). With the defeat and resettlement of the Eastern Türks in 630 and subordination of the Xueyantuo 薛延 陀 in 647, the Tang instituted the jimi fuzhou 羁縻府州 administrative system (lit. "horse bridle prefecture" or "loose reign") on the steppe region dividing it into six area commands and seven prefectures.3 The then-current political leaders were invested as area commanders and prefects. -

Some Notes on the Philological and Historical Relations Between the Terx, Tes and Sine Usu Inscriptions

SOME NOTES ON THE PHILOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL RELATIONS BETWEEN THE TERX, TES AND SINE USU INSCRIPTIONS Volker RYBATZKI* Abstract: Previous scholars have been assuming a close historical and philological connection between the Tes, Terx and Sine Usu inscriptions of the Uighur steppe empire. In this discussion the chronology of the three inscriptions is critically examined with the result that a new one is offered. With regard to the philological similarities it is shown that these are much less than has been supposed which is due to the fact that the function of the three inscription is not identical. Whereas the Sine usu inscription is connected with a grave structure, the Terx and Tes inscriptions are kinds of boundary stones with inscription. Key words: Uighur steppe empire, runic inscriptions, Tes, Terx, Sine Usu, chronology, philological relations, dating. Some Notes on the Philological and Historical Relations Between the Terx, Tes and Sine Usu Inscriptions Özet: Önceki araştırıcılar, Uygur Bozkır Kağanlığı’nın Tes, Taryat ve Şine Usu Yazıtları arasında yakın bir tarihî ve filolojik bağlantı olduğunu varsaymaktadır. Bu tartışmada bu üç yazıtın kronolojisi, bir yenisi sunulan sonuçla eleştirel olarak incelenmiştir. Filolojik benzerliklerle ilgili olarak, bu üç yazıtın işlevinin aynı olmadığı gerçeğinden ötürü, varsayılandan çok daha az olduğu gösterilmiştir. Şine Usu Yazıtı mezar yapısıyla ilişkiliyken, Taryat ve Tes Yazıtları yazılı sınır işaretleri türündendir. Anahtar kelimeler: Uygur Bozkır Kağanlığı, runik yazıtlar, Tes, Taryat, Şine Usu, kronoloji, filolojik ilişkiler, tarih verme. * Doç. Dr. Helsinki Üniversitesi, [email protected] 2011 - 1 71 Some Notes on the Philological and Historical Relatıons Between The Terx, Tes And Sine Usu Inscriptions The idea of this article has a rather long story and goes back to two articles, published in 1971 and 1982 respectively, by two great Turcologists. -

Proposal to Encode the Old Turkic Ligature ORKHON CI

L2/19-069 2019-02-17 Proposal to encode the Old Turkic ligature ORKHON CI Anshuman Pandey [email protected] pandey.github.io/unicode February 17, 2019 1 Proposed character Glyph Codepoint Character name 10C49 OLD TURKIC LIGATURE ORKHON CI 2 Description The character represents the syllable [či]. In this proposal, it is transliterated as c͜ i, where the tie indicates that the value is represented by a single character. The is attested in the Old Turkic inscription of Tonyukuk, in the word kältäčimiz, which occurs in the seventh line on the south-facing side of the first pillar. The full line is given below (rotated 90 degrees counter-clockwise from the original vertical orientation; see fig. 1 for inscription), and the ligature is indicated by the arrow: A digitization of the text using the Unicode encoding and representative glyphs for Old Turkic reads as follows, with the addition of (in red): :ఀఖఀఖ :ఀధఆఴ :ఀఖఆఴ :ఀలఏఉృ :ఀఘఋ :ఀపృఃశ :ఀభఇ :ాఢ఼యఞఝఠఏకఇ :ఽఞఆఉణఆఘ ఢతఇఀన :ఀతఆఢఉ :కఢఠచ :కఢఇా :భఀఋలఇఀచ :ఀకఆ yoγun bolsar : üzgülü͜ k : alp ärmiš : öŋrä : q͜ ii̮ tañda : birijä : tabγačda : qurija : quridin͜ ta : ji̮ rija : oγuzda : iki üč biŋ : sümüz : kältäc͜ imiz : bar mu nä : in͜ čä ötüntim : 1 Proposal to encode the Old Turkic ligature ORKHON CI Anshuman Pandey The character is a ligature of ల U+10C32 OLD TURKIC LETTER ORKHON EC + ః U+10C03 OLD TURKIC LETTER ORKHON I, in which ః is incorporated into the vertical stroke of ల. The c͜ i occurs simultaneously with ఃల ci, which is used throughout the inscription for the normative representation of [či]. -

The Old Turkic Script

The Old Turkic Script Abdugafur A. Rakhimov In brief about history of Script. he ORHONO-YENISEI INSCRIPTIONS, the most ancient writings, monuments of the Turkic people. In 1696-1722 years these inscriptions are opened by Russian scientists TS.Remezov, F.Stralenberg, D.Messershmid in top of the current of the Yenisei. In 1889, on the rivers Orkhons (Mongolia) by .M.Jadrintsev is opened. In 1893, these inscriptions are decoded by the Danish linguist V.Tomsen. And for the first time are read by Russian linguist V.V.Radlov (1894). The Orhono-yenisei inscriptions concern by 7-11 centuries. Seven groups the Orhono-Yenisei inscriptions are known: Baikal, Yenisei, Mongolian, Altai, East Turkistan, Central Asian, and East European. Accordingly they belong to the breeding the union of the Kurgan, the empire of the Kirghiz, the empire of the East Turkic, the empire of the West Turkic, the empire of the Uigur (in Mongolia), the state of the Uigur (in East Turkistan), Khazars (Chazars) and Pechenegs. On a genre accessory are allocated: historically-biographic stone-letters texts of Mongolia; lyrics of texts of Yenisei; legal documents, magic and religious texts (on a paper) from East Turkistan; memorable inscriptions on rocks, stones and struc- tures; labels on household subjects. The inscriptions of Mongolia stating history 2nd East Turkic and the empire of the Uigur have the greatest historical value. The Font Base. It is known, that (La)TEX use only the fonts which have specially been written by Donald Knut in the language of the METAFONT Program. Here, we also used METAFONT what to create the Old Turkic script (Gokturk script or Orkhon script or Orkhon-Yenisey script). -

The Written Monuments of the Ancient Turks and the Tuvinian Poetry

Arts and Humanities Open Access Journal Review Article Open Access The written monuments of the ancient turks and the tuvinian poetry Abstract Volume 2 Issue 6 - 2018 The Author examines the poetic features of ancient Turkic texts, comparing them with Lyudmila Mizhit modern Tuvan poetry. Three-line inscription of the ancient Turks are studied as one of Tuvan Institute of Humanitarian and Applied Socio-economic possible origins of Tuvan poetic genre “ozhuk dazhy” (“stones of the hearth”), which Research 4 Kochetov Str, Republic of Tuva, Russia confirms the continuity of traditions ancient and modern literature. Correspondence: Lyudmila Mizhit, Tuvan Institute of Keywords: the monuments of ancient Turkic, Orkhon-Yenisey script, Tuvinian Humanitarian and Applied Socio-economic Research 4 poetry, epitaph lyrics, tercet, poetic triad, three line form “ozhuk dazhy”, continuity Kochetov Str, Republic of Tuva, Russia, Email Received: June 30, 2018 | Published: December 21, 2018 Introduction inscriptions, about 90 of them are on the territory of Tuva.1 In this connection, the Republic of Tyva regularly since 1993 (the year of the The descendants of the ancient Turkic ethnic groups of Central Asia 100 anniversary of deciphering) organizes the scientific conference - the Tuvinians are a nation with a long history, a kind of spiritual and devoted to ancient Turkic renice that come specialists from all over material culture. Being the homeland of the Turkic peoples, Tuva saves the world. Runic inscriptions of the ancient Turks, being one of the the burial mounds of Scythians (called «Arzhaan-1», «Arzhaan-2») fundamental layers of Turkic literature, have artistic merit - epic and Huns, stone sculptures and steles with the inscriptions «bеngű principle, complex space-time continuum, the characteristic style and taş» («eternal stone») of the ancient Turks, Uighurs and Kyrgyzs from the internal organization of the text, etc. -

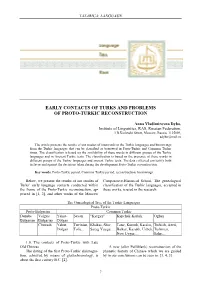

Early Contacts of Turks and Problems of Proto-Turkic Reconstruction

TATARICA: LANGUAGE EARLY CONTACTS OF TURKS AND PROBLEMS OF PROTO-TURKIC RECONSTRUCTION Anna Vladimirovna Dybo, Institute of Linguistics, RAS, Russian Federation, 1 B.Kislovski Street, Moscow, Russia, 1125009, [email protected] The article presents the results of our studies of loanwords in the Turkic languages and borrowings from the Turkic languages that can be classified as borrowed in Proto-Turkic and Common Turkic times. The classification is based on the availability of these words in different groups of the Turkic languages and in Ancient Turkic texts. The classification is based on the presence of these words in different groups of the Turkic languages and ancient Turkic texts. The data collected can testify both in favor and against the decisions taken during the development Proto-Turkic reconstruction. Key words: Proto-Turkic period, Common Turkic period, reconstruction, borrowings. Below, we present the results of our studies of Comparative-Historical School. The genealogical Turks’ early language contacts conducted within classification of the Turkic languages, accepted in the frame of the Proto-Turkic reconstruction, ap- these works, is used in the research. peared in [1, 2], and other works of the Мoscow The Genealogical Tree of the Turkic Languages Proto-Turkic Proto-Bulgarian Common Turkic Danube Volgaic Yakut- Sayan "Kyrgyz" Kypchak-Karluk Oghuz Bulgarian Bulgarian Dolgan Chuvash Yakut, Tuvinian, Khakas, Shor, Tatar, Kumuk, Karaim, Turkish, Azeri, Dolgan Tofa,... Saryg Yuygu, ... Balkar, Kazakh, Uzbek, Turkmen, New Uygur,… Salar,... 1.0. The contacts of Proto-Turkic with Late Old Chinese A new (after Pulliblank) reconstruction of the The dating of the first Proto-Turkic disintegra- phonetic history of Chinese which we are guided tion, achieved by means of glottochronolоgy, is by in our conclusions can be seen in: [3, 4, 5].