Some Thoughts on Ötükän

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

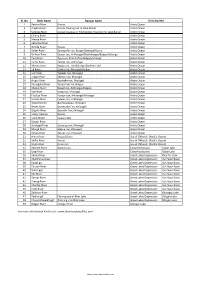

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

Journal Biology 2004 3

Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences 2004 Vol. 2(1): 39-42 Hydrochemical Characteristics of Selenge River and its Tributaries on the Territory of Mongolia Bazarova J.G. 1, Dorzhieva S.G.1, Bazarov B.G. 1, Barkhutova D.D.2, Dagurova O.P.2, Namsaraev B.B. 2 and Zhargalova S.O.2 1Baikal Institute of Nature Management of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, 2Institute of General and Experimental Biology of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Hydrochemical research of the Selenge and its main tributary the Orkhon river on the territory of Mongolia has been conducted. Concentrations of the main water ions were measured. Distribution of - + heavy metals was determined. Dynamics of biogenic elements (NO3 , NH4 , phosphates) and degree of phenol pollution was determined. Key words: Baikal, biogenic, heavy metals, ions, phenol, Selenge River Introduction river is polluted along its entire length. To assess the current ecological condition in the Mongolian During the last 30-40 years Lake Baikal has part of the Selenge river basin, it is necessary to been influenced by various anthropogenic factors. implement hydrobiological and hydrochemical Industrial and household waste water have changed monitoring. It requires information not only of the chemical composition of Baikal with a chemical composition, but of biogenic components deterioration in water quality in the basin territory. in the processes of accumulation and According to sustainable development policy, transformation in water, bottom sediments and river protection of Baikal region is considered -

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River Valley Results of the 2005 Joint American-Mongolian Expedition to Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, Ogii nuur, Arkhangai aimag, Mongolia David E. Purcell and Kimberly C. Spurr Flagstaff, Arizona (USA) During the summer of 2005 an archaeological investigations, and What is known points to this area archaeological expedition jointly their results, are the focus of this as one of the most important mounted by the Silkroad Foun- article, which is a preliminary and cultural regions in the world, a fact dation of Saratoga, California, incomplete record of the project recently recognized by the U.S.A. and the Mongolian National findings. Not all of the project data UNESCO through designation of University, Ulaanbataar, investi- — including osteological analysis of the Orkhon Valley as a World gated two sites near the the burials, descriptions or maps Heritage Site in 2004 (UNESCO confluence of the Tamir River with of the graves, or analyses of the 2006). Archaeological remains the Orkhon River in the Arkhangai artifacts — is available as of this indicate the region has been aimag of central Mongolia (Fig. 1). writing. Consequently, the greater occupied since the Paleolithic (circa The expedition was permitted emphasis falls on one of the two 750,000 years before present), (Registration Number 8, issued sites. It is hoped that through the with Neolithic sites found in great June 23, 2005) by the Ministry of Silkroad Foundation, the many numbers. As early as the Neolithic Education, Culture and Science of different collections from this period a pattern developed in Mongolia. The project had multiple project can be reunited in a which groups moved southward goals: archaeological investiga- scholarly publication. -

Spring 2010 Far Horizons Newsletter

NEWSLETTER FAR HORIZONS ARCHAEOLOGICAL & CULTURAL TRIPS Volume 15, Number 1 • Spring 2010 Published Erratically by Far Horizons • P.O. Box 2546 • San Anselmo, CA 94979 USA (800) 552-4575 • (415) 482-8400 • fax (415) 482-8495 • www.farhorizons.com • email: [email protected] Dear Travelers, I am delighted to dedicate this newsletter to those participants who travel with Far Horizons repeatedly – thank you! In fact, we have included articles from some of our frequent travelers in which they eloquently describe their experiences exploring remarkable destinations with our fabulous study leaders. Don’t miss these evocative accounts of their adventures. There are only a very few spaces remaining on the September trip led by Professor Jonathan Phillips of History Channel fame. I am so pleased that people are excited about our Crusades trip! By the way, look for Professor Jonathan Phillips’ new book, Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades. We plan to design more itineraries relating to the medieval era, so keep watching our webpage. Are you a Bob Brier enthusiast (do you know anyone who isn’t!)? There are still a few spaces left on Bob’s Egypt in Rome May 10-20, 2010, and Oases of Egypt Oct 29 - Nov 15, 2010. Plus Bob Brier heads to Sudan in March of 2011. Be sure and read what former travelers have to say about Bob’s trips and register soon! With this newsletter we begin a new series written by Heather Stoeckley and Sara Barbieri, two members of the Far Horizons team who travel several times each year with our groups as tour manager. -

Sundowners Overland - Gobi Desert Explorer Page 1 of 6 Itinerary

Journey Itinerary Gobi Desert Explorer Days Westbound, Eastbound Countries Distance Activity level 16 Ulaanbaatar to Ulaanbaatar Mongolia 1,750 km Discover the very best of Mongolia, from the bustling capital Ulaanbaatar we journey across the steppe to Kharkhorin. We will encounter ancient Buddhist monasteries and the remarkable diversity of the Gobi Desert; sacred mountains, dinosaur ‘cemeteries’, flaming cliffs, singing sand dunes and spectacular canyons. Sundowners Overland - Gobi Desert Explorer Page 1 of 6 Itinerary Day 1: Ulaanbaatar Mongolia is the world’s most sparsely populated country with just 3 million people inhabiting the 1.5 million square kilometres of pristine desert, steppe and mountain. Almost half the population lives in its frenetic capital Ulaanbaatar where we will start our journey. Join your Tour Leader and fellow travellers on Day 1 at 5:00pm for your Welcome Meeting as detailed on your joining instructions. Meals - Day 1 – Dinner Day 2: To Bayangobi via Khustai National Park Beyond the city one million Mongolian’s still live a traditional nomadic or semi nomadic life and the horse is central to their existence. We visit the Gandan Monastery, with its huge gold Buddha, the spiritual home of the Mongolian people, before traveling to the Khustai National Park where wild horses, known as Tahki or Przewalski horses are bred and reintroduced to the wild. Once close to extinction, Takhi are the world’s only true wild horse. Mongolia is a country with such diverse landscapes and today we continue our way across the steppe to experience the uniqueness of the Bayangobi. Here we have the opportunity to hike in the stunning sand dunes that stretch over a distance of 80kms. -

Mongolian Vision Tours

Mongolian Vision Tours FROM DESERT TO STEPPE Nomadic Mongolia waits for you in this tour in the heart of the nomadic life. From family to family, you will start your horse trek tour by the green Orkhon Valley, before going deeper in the remote area of Naiman Nuur. Then you'll go towards South, where the track disappears to give place to a legendary spot: the Gobi Desert, and the arid majesty of its lunar landscapes, with its towering rocky formations, frozen canyon and sand dunes. Day1. The granite formations of Baga Gazriin Chuluu Ulan Bator – Baga Gazriin Chuluu 250km Visit of Mountains Baga Gazriin Chuluu, where we'll observe stunning granite rock formations eroded by the violent elements of this area. In the 19th century, two respected lamas lived here, and we still can see their inscriptions in the rock. According to the legend, Genghis Khan to is supposed to have lived in this wonderful area where it's pleasant to walk. Stay overnight: Nomadic Family’s ger or tourist ger camp Day2. The great white stupa in the desert Baga Gazar Chuluu – white stupa 220km We travel in one of the emptiest areas of Mongolia. Between rock desert and semi-arid steppes, we reach the white stupa, Tsagaan Suvarga. For centuries, this 30-metre (98,43 feet) high, abrupt, stupa- shaped mountain, is honored by the Mongolians. The traveler will be surprised by the sumptuous lunar landscapes that evoke the end of the world, and by the many fossils. This area was totally covered by the sea a few million years ago. -

Mongolia Exotic Tour

Mongolia Exotic Tour Key Information: Trip Length: 9 days/8 nights. Trip Type: Easy to Moderate. Tour Code: SMT-ORKHON-9D Specialty Categories: Adventure Expedition, Cultural Journey, Camel riding, Driving tour, Eco-Travel, Hiking, Hot spa, Local Culture, Nature & Wildlife. Meeting/Departure Points: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (excluding flights). Small Groups: 2-16 travelers-guaranteed! Best Season: Daily, June-September. Total Distance: about 2000kms/1243miles. Airfare or Train Included: No. Tour Customizable: Yes Tour Highlights: Upon your arrival in Ulaanbaatar, meet Samar Magic Tours team. Mongolia Exotic Tour takes you to the Natural Wonders of Central Mongolia. This journey designed especially for small groups, families, private, and funny travel. Exploration to Karakorum-the Genghis (Chinggis) Khan's 13th century capital, Orkhon Waterfall (also called Ulaan Tsutgalan)-this is perfect for swimming, fishing, short trekking and walks around the surrounding area, stop at VIII century Turkish monuments in the Orkhon Valley, Tsenkher Hot Spa and many more. Karakorum was the capital of the Mongol Empire in the 13th century and of the Northern Yuan in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in the north-western corner of the Ovorkhangai Province of Mongolia, near today's town of Kharkhorin, and adjacent to the Erdene Zuu monastery. They are part of the upper part of the World Heritage Site Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape. Ride horses on the steppes, meeting nomadic people, staying in a traditional tent, seeing grasslands and beautiful vistas. You will need to bring your Binoculars, telescopes and tripod. We would be pleased to have you join us! The Best Time to Travel to Mongolia: Begins in June. -

Unit Plan – Silk Road Encounters

Unit Plan – Silk Road Encounters: Real and/or Imagined? Prepared for the Central Asia in World History NEH Summer Institute The Ohio State University, July 11-29, 2016 By Kitty Lam, History Faculty, Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy, Aurora, IL [email protected] Grade Level – 9-12 Subject/Relevant Topics – World History; trade, migration, nomadism, Xiongnu, Turks, Mongols Unit length – 4-8 weeks This unit plan outlines my approach to world history with a thematic focus on the movement of people, goods and ideas. The Silk Road serves a metaphor for one of the oldest and most significant networks for long distance east-west exchange, and offers ample opportunity for students to conceptualize movement in a world historical context. This unit provides a framework for students to consider the different kinds of people who facilitated cross-cultural exchange of goods and ideas and the multiple factors that shaped human mobility. This broad unit is divided into two parts: Part A emphasizes the significance of nomadic peoples in shaping Eurasian exchanges, and Part B focuses on the relationship between religion and trade. At the end of the unit, students will evaluate the use of the term “Silk Road” to describe this trade network. Contents Part A – Huns*, Turks, and Mongols, Oh My! (Overview) -------------------------------------------------- 2 Introductory Module ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Module 1 – Let’s Get Down to Business to Defeat the Xiongnu ---------------------------------- -

Radiation Background in the Some Towns of Uvurkhangai Province in Mongolia

International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Bioresearch Vol. 2, No. 01; 2017 www.ijaeb.org RADIATION BACKGROUND IN THE SOME TOWNS OF UVURKHANGAI PROVINCE IN MONGOLIA Ts.Erkhembayar1, N.Yasuda2, Y.Izumi2, Y.Matuo2, N.Chimedtsogzol1, Ch.Tsolmonchimeg1, B.Gandulam1 1-Department of physics, School of Applied Science, Mongolian University of Science and Technology 2-Research Institute of Nuclear Engineering, University of Fukui, Mangolia ABSTRACT This paper was focused on determination of radiation level around Kharkhorin and Khujirt towns of Uvurkhangai province. We have determined radiation background by radiation survey meters “Atomtex” and “Radi PA-1100(Horiba)”. The results were compared with the world and Japanese major cities radiation level. Keywords: radiation, dose, level, dosimeter, survey meter INTRODUCTION UVURKHANGAI AIMAG /PROVINCE/ Territory - 24,286 square miles (62,900 sq. km.) Center - Arvaikheer town, located 261 miles (420 km.) from Ulaanbaatar. Number of somons /towns/- 19 Population 118,400 Figure 1. Map of Uvurkhangai province in Mongolia www.ijaeb.org Page 68 International Journal of Agriculture, Environment and Bioresearch Vol. 2, No. 01; 2017 www.ijaeb.org Uvurkhangai aimag was established in 1931. Uvurkhangai aimag is located in the central part of Mongolia. The Khangai mountain stretches in the North-West, and the Altai mountain towers in the south-west. The steppe lies in the middle of the territory. The Gobi desert is located in the South. The annual average temperature is around 34° F (1° C), and the average precipitation is about 5 inches (135 mm.). The soil in the south of the area is semi-desert grey and steppe pale areas, in the north part of the area it is mountain type brown and black. -

TURKIC POLITICAL HISTORY Early Postclassical (Pre-Islamic) Period

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE Richard Dietrich, Ph.D. TURKIC POLITICAL HISTORY Early Postclassical (Pre-Islamic) Period Contents Part I : Overview Part II : Government Part III : Military OVERVIEW The First Türk Empire (552-630) The earliest mention of the Türks is found in 6th century Chinese sources in reference to the establishment of the first Türk empire. In Chinese sources they are called T’u-chüeh (突厥, pinyin Tūjué, and probably pronounced tʰuot-küot in Middle Chinese), but refer to themselves in the 7th - 8th century Orkhon inscriptions written in Old Turkic as Türük (��ఇ఼�� ) or Kök Türük (�� �ఇ �� :�� �ఇ �఼ �� ). In 552 the Türks emerged as a political power on the eastern steppe when, under the leadership of Bumin (T’u-men in the Chinese sources) from the Ashina clan of the Gök Türks, they revolted against and overthrew the Juan-juan Empire (pinyin Róurán) that had been the most significant power in that region for the previous century and a half. After defeating the Juan-juan and taking their territories, Bumin took the title of kaghan, supreme leader, while his brother Istemi (also Istämi or Ishtemi, r. 552-576) became the yabghu, a title indicating his subordinate status. Bumin was the senior leader, ruling the eastern territories of the empire, while Istemi ruled the western territories. Bumin died in 553, was briefly followed by his son followed by his son Kuo-lo (Qara?), and then by another of his sons, Muhan (or Muqan, r. 553-572). In the following decades Istemi and Muhan extended their rule over the Kitan in Manchuria, the Kirghiz tribes in the Yenisei region, and destroyed the Hephthalite Empire in a joint effort with the Sasanians. -

MONGOLIA Environmental Monitor 2003 40872

MONGOLIA Environmental Monitor 2003 40872 THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, NW Washington, D. C. 20433 U.S.A. Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Tel: 202-477-1234 Fax: 202-477-6391 Telex: MCI 64145 WORLDBANK MCI 248423 WORLDBANK Internet: http://worldbank.org THE WORLD BANK MONGOLIA OFFICE Ulaanbaatar, 11 A Peace Avenue Ulaanbaatar 210648, Mongolia Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK ENVIRONMENT MONITOR 2003 Land Resources and Their Management THE WORLD BANK CONTENTS PREFACE IV ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS V SECTION I: PHYSICAL FEATURES OF LAND 2 SECTION II: LAND, POVERTY, AND LIVELIHOODS 16 SECTION III: LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL DIMENSIONS OF LAND MANAGEMENT 24 SECTION IV: FUTURE CHALLENGES 32 MONGOLIA AT A GLANCE 33 NOTES 34 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 The World Bank Mongolia Office Ulaanbaatar, 11 A Peace Avenue Ulaanbaatar 210648, Mongolia All rights reserved. First printing June 2003 This document was prepared by a World Bank Team comprising Messrs./Mmes. Anna Corsi (ESDVP), Giovanna Dore (Task Team Leader), Tanvi Nagpal, and Tony Whitten (EASES); Robin Mearns (EASRD); Yarissa Richmond Lyngdoh (EASUR); H. Ykhanbai (Mongolia Ministry of Nature and Environment). Jeffrey Lecksell was responsible for the map design. Photos were taken by Giovanna Dore and Tony Whitten. Cover and layout design were done by Jim Cantrell. Inputs and comments by Messrs./Mmes. John Bruce (LEGEN), Jochen Becker, Gerhard Ruhrmann (Rheinbraun Engineering und Wasser - GmbH), Nicholas Crisp, John Dick, Michael Mullen (Food and Agriculture Organization), Clyde Goulden (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia), Hans Hoffman (GTZ), Glenn Morgan, Sulistiovati Nainggolan (EASES), and Vera Songwe (EASPR) are gratefully acknowledged.