Some Notes on the Philological and Historical Relations Between the Terx, Tes and Sine Usu Inscriptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TURKIC POLITICAL HISTORY Early Postclassical (Pre-Islamic) Period

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE Richard Dietrich, Ph.D. TURKIC POLITICAL HISTORY Early Postclassical (Pre-Islamic) Period Contents Part I : Overview Part II : Government Part III : Military OVERVIEW The First Türk Empire (552-630) The earliest mention of the Türks is found in 6th century Chinese sources in reference to the establishment of the first Türk empire. In Chinese sources they are called T’u-chüeh (突厥, pinyin Tūjué, and probably pronounced tʰuot-küot in Middle Chinese), but refer to themselves in the 7th - 8th century Orkhon inscriptions written in Old Turkic as Türük (��ఇ఼�� ) or Kök Türük (�� �ఇ �� :�� �ఇ �఼ �� ). In 552 the Türks emerged as a political power on the eastern steppe when, under the leadership of Bumin (T’u-men in the Chinese sources) from the Ashina clan of the Gök Türks, they revolted against and overthrew the Juan-juan Empire (pinyin Róurán) that had been the most significant power in that region for the previous century and a half. After defeating the Juan-juan and taking their territories, Bumin took the title of kaghan, supreme leader, while his brother Istemi (also Istämi or Ishtemi, r. 552-576) became the yabghu, a title indicating his subordinate status. Bumin was the senior leader, ruling the eastern territories of the empire, while Istemi ruled the western territories. Bumin died in 553, was briefly followed by his son followed by his son Kuo-lo (Qara?), and then by another of his sons, Muhan (or Muqan, r. 553-572). In the following decades Istemi and Muhan extended their rule over the Kitan in Manchuria, the Kirghiz tribes in the Yenisei region, and destroyed the Hephthalite Empire in a joint effort with the Sasanians. -

Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV

BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia BUDAG BUDAGOV Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 Sponsored by VELIYEV RUSTAM SALEH oglu T ranslated by ZAHID MAHAMMAD oglu AHMADOV Edited by FARHAD MAHAMMAD oglu MUSTAFAYEV Budagov B.A. Turkic Toponyms of Eurasia. - Baku “Elm”, 1997, -1 7 4 p. ISBN 5-8066-0757-7 The geographical toponyms preserved in the immense territories of Turkic nations are considered in this work. The author speaks about the parallels, twins of Azerbaijani toponyms distributed in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Altay, the Ural, Western Si beria, Armenia, Iran, Turkey, the Crimea, Chinese Turkistan, etc. Be sides, the geographical names concerned to other Turkic language nations are elucidated in this book. 4602000000-533 В ------------------------- 655(07)-97 © “Elm” Publishing House, 1997 A NOTED SCIENTIST Budag Abdulali oglu Budagov was bom in 1928 at the village o f Chobankere, Zangibasar district (now Masis), Armenia. He graduated from the Yerevan Pedagogical School in 1947, the Azerbaijan State Pedagogical Institute (Baku) in 1951. In 1955 he was awarded his candidate and in 1967 doctor’s degree. In 1976 he was elected the corresponding-member and in 1989 full-member o f the Azerbaijan Academy o f Sciences. Budag Abdulali oglu is the author o f more than 500 scientific articles and 30 books. Researches on a number o f problems o f the geographical science such as geomorphology, toponymies, history o f geography, school geography, conservation o f nature, ecology have been carried out by academician B.A.Budagov. He makes a valuable contribution for popularization o f science. -

Old Turkic Script

Old Turkic script The Old Turkic script (also known as variously Göktürk script, Orkhon script, Orkhon-Yenisey script, Turkic runes) is the Old Turkic script alphabet used by the Göktürks and other early Turkic khanates Type Alphabet during the 8th to 10th centuries to record the Old Turkic language.[1] Languages Old Turkic The script is named after the Orkhon Valley in Mongolia where early Time 6th to 10th centuries 8th-century inscriptions were discovered in an 1889 expedition by period [2] Nikolai Yadrintsev. These Orkhon inscriptions were published by Parent Proto-Sinaitic(?) Vasily Radlov and deciphered by the Danish philologist Vilhelm systems Thomsen in 1893.[3] Phoenician This writing system was later used within the Uyghur Khaganate. Aramaic Additionally, a Yenisei variant is known from 9th-century Yenisei Syriac Kirghiz inscriptions, and it has likely cousins in the Talas Valley of Turkestan and the Old Hungarian alphabet of the 10th century. Sogdian or Words were usually written from right to left. Kharosthi (disputed) Contents Old Turkic script Origins Child Old Hungarian Corpus systems Table of characters Direction Right-to-left Vowels ISO 15924 Orkh, 175 Consonants Unicode Old Turkic Variants alias Unicode Unicode U+10C00–U+10C4F range See also (https://www.unicode. org/charts/PDF/U10C Notes 00.pdf) References External links Origins According to some sources, Orkhon script is derived from variants of the Aramaic alphabet,[4][5][6] in particular via the Pahlavi and Sogdian alphabets of Persia,[7][8] or possibly via Kharosthi used to write Sanskrit (cf. the inscription at Issyk kurgan). Vilhelm Thomsen (1893) connected the script to the reports of Chinese account (Records of the Grand Historian, vol. -

The Decipherment of the Turkish Runic Inscriptions and Its Effects on Turkology in East and West

THE DECIPHERMENT OF THE TURKISH RUNIC INSCRIPTIONS AND ITS EFFECTS ON TURKOLOGY IN EAST AND WEST Wolfgang-E. SCHARLIPP Introduction The term “Runes” for the letters of the Old Turkish alphabet, used mainly for inscriptions but also a few manuscripts, has lately been criticized by some Turkish scientists for its misleading meaning. As “Runes” is originally the term of the old Germanic alphabet, this term could suggest a Germanic origin of the Turkish alphabet. Indeed the term indicates nothing more than a similarity of shape that these alphabets have in common, which has also created the term “runiform” letters. As such nationalist hair-splitting does not contribute to scientific discussion, we will in the following use the term “Turkish runes” with a good conscience. This contribution aims at showing similarities and differences between the ways that research into this alphabet and the texts written in it, went among Turkish scientists on the one side and Non-Turkish scientists on the other side. We will also see how these differences came into existence. In order to have a sound basis for our investigation we will first deal with the question how the Turkish runes were deciphered. We will then see how the research into the inscriptions continued among Western scholars, before we finally come to the effects that this research had on scientists in Turkey, or to be more precise, in the Ottoman Empire and then in the Republic of Turkey. In the 19th century Several expeditions were sent out in order to collect material concerning the stone inscriptions in Central Asia. -

Proposal to Encode the Old Turkic Ligature ORKHON CI

L2/19-069 2019-02-17 Proposal to encode the Old Turkic ligature ORKHON CI Anshuman Pandey [email protected] pandey.github.io/unicode February 17, 2019 1 Proposed character Glyph Codepoint Character name 10C49 OLD TURKIC LIGATURE ORKHON CI 2 Description The character represents the syllable [či]. In this proposal, it is transliterated as c͜ i, where the tie indicates that the value is represented by a single character. The is attested in the Old Turkic inscription of Tonyukuk, in the word kältäčimiz, which occurs in the seventh line on the south-facing side of the first pillar. The full line is given below (rotated 90 degrees counter-clockwise from the original vertical orientation; see fig. 1 for inscription), and the ligature is indicated by the arrow: A digitization of the text using the Unicode encoding and representative glyphs for Old Turkic reads as follows, with the addition of (in red): :ఀఖఀఖ :ఀధఆఴ :ఀఖఆఴ :ఀలఏఉృ :ఀఘఋ :ఀపృఃశ :ఀభఇ :ాఢ఼యఞఝఠఏకఇ :ఽఞఆఉణఆఘ ఢతఇఀన :ఀతఆఢఉ :కఢఠచ :కఢఇా :భఀఋలఇఀచ :ఀకఆ yoγun bolsar : üzgülü͜ k : alp ärmiš : öŋrä : q͜ ii̮ tañda : birijä : tabγačda : qurija : quridin͜ ta : ji̮ rija : oγuzda : iki üč biŋ : sümüz : kältäc͜ imiz : bar mu nä : in͜ čä ötüntim : 1 Proposal to encode the Old Turkic ligature ORKHON CI Anshuman Pandey The character is a ligature of ల U+10C32 OLD TURKIC LETTER ORKHON EC + ః U+10C03 OLD TURKIC LETTER ORKHON I, in which ః is incorporated into the vertical stroke of ల. The c͜ i occurs simultaneously with ఃల ci, which is used throughout the inscription for the normative representation of [či]. -

The Old Turkic Script

The Old Turkic Script Abdugafur A. Rakhimov In brief about history of Script. he ORHONO-YENISEI INSCRIPTIONS, the most ancient writings, monuments of the Turkic people. In 1696-1722 years these inscriptions are opened by Russian scientists TS.Remezov, F.Stralenberg, D.Messershmid in top of the current of the Yenisei. In 1889, on the rivers Orkhons (Mongolia) by .M.Jadrintsev is opened. In 1893, these inscriptions are decoded by the Danish linguist V.Tomsen. And for the first time are read by Russian linguist V.V.Radlov (1894). The Orhono-yenisei inscriptions concern by 7-11 centuries. Seven groups the Orhono-Yenisei inscriptions are known: Baikal, Yenisei, Mongolian, Altai, East Turkistan, Central Asian, and East European. Accordingly they belong to the breeding the union of the Kurgan, the empire of the Kirghiz, the empire of the East Turkic, the empire of the West Turkic, the empire of the Uigur (in Mongolia), the state of the Uigur (in East Turkistan), Khazars (Chazars) and Pechenegs. On a genre accessory are allocated: historically-biographic stone-letters texts of Mongolia; lyrics of texts of Yenisei; legal documents, magic and religious texts (on a paper) from East Turkistan; memorable inscriptions on rocks, stones and struc- tures; labels on household subjects. The inscriptions of Mongolia stating history 2nd East Turkic and the empire of the Uigur have the greatest historical value. The Font Base. It is known, that (La)TEX use only the fonts which have specially been written by Donald Knut in the language of the METAFONT Program. Here, we also used METAFONT what to create the Old Turkic script (Gokturk script or Orkhon script or Orkhon-Yenisey script). -

The Written Monuments of the Ancient Turks and the Tuvinian Poetry

Arts and Humanities Open Access Journal Review Article Open Access The written monuments of the ancient turks and the tuvinian poetry Abstract Volume 2 Issue 6 - 2018 The Author examines the poetic features of ancient Turkic texts, comparing them with Lyudmila Mizhit modern Tuvan poetry. Three-line inscription of the ancient Turks are studied as one of Tuvan Institute of Humanitarian and Applied Socio-economic possible origins of Tuvan poetic genre “ozhuk dazhy” (“stones of the hearth”), which Research 4 Kochetov Str, Republic of Tuva, Russia confirms the continuity of traditions ancient and modern literature. Correspondence: Lyudmila Mizhit, Tuvan Institute of Keywords: the monuments of ancient Turkic, Orkhon-Yenisey script, Tuvinian Humanitarian and Applied Socio-economic Research 4 poetry, epitaph lyrics, tercet, poetic triad, three line form “ozhuk dazhy”, continuity Kochetov Str, Republic of Tuva, Russia, Email Received: June 30, 2018 | Published: December 21, 2018 Introduction inscriptions, about 90 of them are on the territory of Tuva.1 In this connection, the Republic of Tyva regularly since 1993 (the year of the The descendants of the ancient Turkic ethnic groups of Central Asia 100 anniversary of deciphering) organizes the scientific conference - the Tuvinians are a nation with a long history, a kind of spiritual and devoted to ancient Turkic renice that come specialists from all over material culture. Being the homeland of the Turkic peoples, Tuva saves the world. Runic inscriptions of the ancient Turks, being one of the the burial mounds of Scythians (called «Arzhaan-1», «Arzhaan-2») fundamental layers of Turkic literature, have artistic merit - epic and Huns, stone sculptures and steles with the inscriptions «bеngű principle, complex space-time continuum, the characteristic style and taş» («eternal stone») of the ancient Turks, Uighurs and Kyrgyzs from the internal organization of the text, etc. -

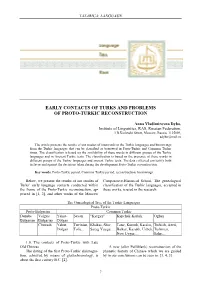

Early Contacts of Turks and Problems of Proto-Turkic Reconstruction

TATARICA: LANGUAGE EARLY CONTACTS OF TURKS AND PROBLEMS OF PROTO-TURKIC RECONSTRUCTION Anna Vladimirovna Dybo, Institute of Linguistics, RAS, Russian Federation, 1 B.Kislovski Street, Moscow, Russia, 1125009, [email protected] The article presents the results of our studies of loanwords in the Turkic languages and borrowings from the Turkic languages that can be classified as borrowed in Proto-Turkic and Common Turkic times. The classification is based on the availability of these words in different groups of the Turkic languages and in Ancient Turkic texts. The classification is based on the presence of these words in different groups of the Turkic languages and ancient Turkic texts. The data collected can testify both in favor and against the decisions taken during the development Proto-Turkic reconstruction. Key words: Proto-Turkic period, Common Turkic period, reconstruction, borrowings. Below, we present the results of our studies of Comparative-Historical School. The genealogical Turks’ early language contacts conducted within classification of the Turkic languages, accepted in the frame of the Proto-Turkic reconstruction, ap- these works, is used in the research. peared in [1, 2], and other works of the Мoscow The Genealogical Tree of the Turkic Languages Proto-Turkic Proto-Bulgarian Common Turkic Danube Volgaic Yakut- Sayan "Kyrgyz" Kypchak-Karluk Oghuz Bulgarian Bulgarian Dolgan Chuvash Yakut, Tuvinian, Khakas, Shor, Tatar, Kumuk, Karaim, Turkish, Azeri, Dolgan Tofa,... Saryg Yuygu, ... Balkar, Kazakh, Uzbek, Turkmen, New Uygur,… Salar,... 1.0. The contacts of Proto-Turkic with Late Old Chinese A new (after Pulliblank) reconstruction of the The dating of the first Proto-Turkic disintegra- phonetic history of Chinese which we are guided tion, achieved by means of glottochronolоgy, is by in our conclusions can be seen in: [3, 4, 5]. -

ON the NAME and TITLES of TONYUQUQ Erhan AYDIN*

Türkbilig, 2019/37: 1-10. ON THE NAME AND TITLES OF TONYUQUQ Erhan AYDIN* Abstract: The Tonyuquq inscription is one of the most studied works since its discovery. The name of the proprietor Tonyuquq and the meaning expressed by this name have been discussed quite extensively. The name is read in two different forms in the form of Tonyuquq and Tunyuquq. The name of Tonyuquq was observed once in the inscription of Bilgä Qagan, and once in the inscription of Küli Çor. The lettering of Tonyuquq as a word is different in Bilgä Qagan and Küli Çor inscriptions and Tonyuquq inscription. The difference is based on whether it is written with the consonant ñ or using the letter n or y. One of the topics covered in the present article is about the scripture of the name of Tonyuquq in the inscription that bears his name and in Bilgä Qagan and Küli Çor inscriptions. Another issue covered in the article is the titles used by Tonyuquq and the meanings of these titles. After discussing the meanings of these titles in the general Turkish language, the subject is elaborated in detail. The article ends with a collection of the sentences where the name Tonyuquq was mentioned. Keywords: Tonyuquq, Tonyuquq inscription, The old Turkic inscriptions, The Old Turkic, titles. Tonyukuk’un Adı ve Unvanları Üzerine Öz: Tonyukuk yazıtı, bulunduğu günden bugüne kadar üzerinde en çok çalışma yapılan yazıtlardandır. Yazıtın sahibi Tonyukuk’un adı ve bu adın ifade ettiği anlam epeyce tartışılmıştır. Ad, Tonyukuk ve Tunyukuk biçiminde iki farklı biçimde okunmaktadır. Tonyukuk’un adı, kendi yazıtı dışında, Bilge Kağan yazıtında bir kez, ad olarak ise Küli Çor yazıtında bir kez tanıklanmıştır. -

An Introduction to Turkology

A. RÓNA-TAS AN INTRODUCTION TO TURKOLOGY SZEGED 1991 Editionis curam agit KLÁRA SZŐNYI-SÁNDOR PREFACE The contents of this introduction had a long conception period. I tried to re- and reshape it since I begun teaching Turkology at the Attila József Univer- sity, Szeged, Hungary, in 1974.1 first outlined the basic contours of this variant in Bonn in the academic year 1982/83, when I tought there as a visiting profes- sor in the Zentralasiatisches SeminarComing' back to Szeged I changed the language from German to English and used the draft for graduate courses. In the meantime I learnt that several of my colleagues were preparing similar introductions. I almost left my manuscript unfinished when I met some of these colleagues and realized that our approaches were basically different. I became convinced that our respective introductions would fit into a greater framework complementing each other. Thus I set myself to finish the work. Unfortunetely other inevitable duties have hindered me to complete the entire work. This volume is only the first of a series but does not bear this numeral because I am in this respect superstitious. The second volume is practically ready. It will contain the introduction to the sources in the Manichean, Sogdian, Uighur and Arabic scripts. These systems of writing were used to render Old Turkic texts. In a further part I intend to deal with those writing systems in which we find Old Turkic words, names and isolated phrases, such as Chinese, Pahlavi, Geor- gian, Armenian, Greek, Latin, Cyrillic, Hebrew. In an Appendix I shall sum- merize our knowledge on the inscriptions written with the East European "Runic" script(s) wich I consider practically undeciphered. -

İhe Ashete Yazıtı: Yeni Bir Okuma Ve Anlamlandırma Denemesi

bilig BAHAR 2015 / SAYI 73 271-294 İhe Ashete Yazıtı: Yeni Bir Okuma ve Anlamlandırma Denemesi Orçun Ünal∗ Öz Göktürk dönemi yazıtlarından olan İhe Ashete yazıtı, Altun Tamgan Tarkan’ın lahdine ait iki taşın üç yüzüne yazılmış bir mezar anıt yazıtıdır. Yazıt; daha önce W. Radloff, H. N. Or- kun, S. E. Malov, K. Wulff (yayımlanmamış notlar), N. Ser- Odjav, E. B. Rinchen, L. Bazin, L. V. Clark, L. Bold, E. Re- cebov-Y. Memmedov, N. Bazilhan, M. Dobrovits ve T. Ôsawa tarafından okunmuştur, fakat bütün bu okumalarda tatmin edici olmayan bazı kısımlar mevcuttur. Bu yüzden, bu çalışmada iki taşın üç yüzü de tekrar okunacak ve daha önceki okumalara göre her açıdan daha sağlam bir metin ve çeviri or- taya konmaya çalışılacaktır. Anahtar Kelimeler İhe Ashete Yazıtı, Höl Asgat Yazıtı, Eski Türkçe 1. Giriş İhe Ashete yazıtı; Moğolistan’ın Bulgan aymagının Mogod sumunda Tü- lee uul dağının batısında kalan Asgatın Höndiy bölgesindeki Asgat vadi- sinde, N 46º 54´ - E 104º 33´ koordinatlarında (Bazilhan 2005: 124), Orhon Yazıtlarının bulunduğu Koşo-Tsaydam vadisinin yaklaşık 53 km kuzeydoğusunda bulunmaktadır. Yazıtın 2,5 km batısından geçen nehrin adı Höl Asgat’tır. Bu yüzden yazıt literatürde Höl Asgat Yazıtı olarak da anılır. Yazıtın GPS kaydı, Alyılmaz (2003: 185) tarafından 1415 m, 48 U 0335821, UTM 5318946 olarak verilmiştir. İhe Ashete yazıtı; İhe Hüşötü (Küli Çor), Ongin ve Orhon Yazıtları ile birlikte Göktürk dönemine ait yazıtlardandır ve 724 yılına tarihlendirilir (Róna-Tas 1999: 81). Ôsawa (2010: 73) ise yazıtın (Apa) Yegän İrkin tarafından 729 yılında yazıldığını iddia etmektedir. _____________ ∗ Öğr. Gör., Beykent Üniversitesi Meslek Yüksekokulu, Halkla İlişkiler ve Tanıtım Programı – İstanbul / Türkiye [email protected] 271 • bilig BAHAR 2015 / SAYI 73 • Ünal, İhe Ashete Yazıtı: Yeni Bir Okuma ve Anlamlandırma Denemesi • İhe Ashete anıt mezarı, dörder taş duvarı olan iki lahitten (A, B) oluşmak- tadır. -

A Short History of the Bugut Inscription

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE BUGUT INSCRIPTION MEHMET ÖLMEZ ISTANBUL UNIVERSITY Abstract The two Bugut inscriptions from the First Turkic Khaganate in Mongolia are primary sources for the Turkic history, as well as for the history of Sogdian and Mongolian languages. The field research that has been conducted on the bilingual Bugut inscription was quite limited, but the last one has finally solved the mystery of the unknown side of the Bugut inscription. Keywords: Mongolian archeology, First Turkic Khaganate, Bugut inscription When we speak about the Old Turkic inscriptions 1969 is the first publication on the Sogdian inscription, from Mongolia, the Kül Tegin and Bilge Kaghan inscrip- I am going to start with a more detailed outline of their tions from Khöšöö Tsaidam close to Orkhon valley and joint publication: some distance from the Erdene Zuu monastery first come In 1956 the Mongolian archeologist Dordžsuren dis- to mind. Going back over 120 years, the Tunyukuk covered a monument situated at the back side of the stone inscription from Bain Tsokto is also added to the impor- turtle, which was located between the gravestones of tant part of the collection of the Old Turkic inscriptions. Bugut som. Three sides of the stone (the front side (BS I), All three inscriptions, Kül Tegin, Bilge Kaghan and the right side (BS II) and the left side (BS III)) were iden- Tunyukuk are from the second Turkic Kaghanate that tified as Sogdian by Livšic. existed between 682-744 AD. None of the similar inscrip- Although the initial parts of the lines are eroded, half tions from the First Turkic Kaghanate have been discov- of the text is preserved.