Physiological Determinants of Ultramarathon Trail-Running Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Age-Related Changes in Conventional Road Versus Off-Road Triathlon Performance Romuald Lepers, P.J

Age-related changes in conventional road versus off-road triathlon performance Romuald Lepers, P.J. Stapley To cite this version: Romuald Lepers, P.J. Stapley. Age-related changes in conventional road versus off-road triathlon performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, Springer Verlag, 2011, 111 ((8)), pp.1687- 1694. hal-00702344 HAL Id: hal-00702344 https://hal-univ-bourgogne.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00702344 Submitted on 30 May 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 2011, 111(8):1687-1694 Age-related changes in conventional road versus off-road triathlon performance Romuald Lepers1 & Paul J. Stapley2 1 University of Burgundy, Faculty of Sport Sciences, INSERM U887, BP 27877, 21078 Dijon Cedex, FRANCE 2 Balance and Voluntary Movement Lab, Department of Kinesiology and Physical Education, McGill University, 475 Pine Ave West, Montreal, Quebec, H2W1S4, CANADA Running title: Age and Performance in off-road triathlon Corresponding author: Romuald Lepers Université de Bourgogne Faculté des Sciences du Sport INSERM U887 BP 27877 21078 Dijon Cedex France Tel : +33.3.80.39.67.60 Fax : +33.3.80.39.67.02 Email : [email protected] Abstract The aims of this study were: i) to analyze age-related declines in swimming, cycling, and running performances for road-based and off-road triathlons, and ii) to compare age-related changes in these three disciplines between road-based and off-road triathlons. -

Physiology of Adventure Racing – with Emphasis on Circulatory Response and Cardiac Fatigue

From the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden PHYSIOLOGY OF ADVENTURE RACING – WITH EMPHASIS ON CIRCULATORY RESPONSE AND CARDIAC FATIGUE C. Mikael Mattsson Stockholm 2011 Supervisors Main supervisor Björn Ekblom, M.D., Ph.D., Professor emeritus Åstrand Laboratory of Work Physiology The Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden Co-supervisor Bo Berglund, M.D., Ph.D., Associate professor Department of Medicine Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden External mentor Euan A. Ashley, M.D., Ph.D., Assistant professor Department of Medicine Stanford University, CA, USA Faculty Opponent Keith P. George, Ph.D., Professor Research Institute for Sport and Exercise Sciences Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, England Examination Board Eva Nylander, M.D., Ph.D., Professor Department of Medical and Health Sciences Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden Tomas Jogestrand, M.D., Ph.D., Professor Department of Laboratory Medicine Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Mats Börjesson, M.D., PhD., Associate professor Department of Emergency and Cardiovascular Medicine University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Front cover: Explore Sweden 2010. Photo: Krister Göransson. All previously published papers were reproduced with permission from the publisher. Published by Karolinska Institutet. Printed by Larserics Digital Print AB. © C. Mikael Mattsson, 2011 ISBN 978-91-7457-262-9 “We'll go because it's Thursday, and we'll go to wish everybody a Very Happy Thursday.” Winnie-the-Pooh 1 ABSTRACT The overall aims of this thesis were to elucidate the circulatory responses to ultra-endurance exercise (Adventure Racing), and furthermore, to contribute to the clarification of the so called “exercise-induced cardiac fatigue” in relation to said exercise. -

Physiological Demands of Mountain Running Races

Rodríguez-Marroyo1, J.A. et al.: PHYSIOLOGICAL DEMANDS OF MOUNTAIN... Kinesiology 50(2018) Suppl.1:60-66 PHYSIOLOGICAL DEMANDS OF MOUNTAIN RUNNING RACES Jose A. Rodríguez-Marroyo1, Javier González-Lázaro2,3, Higinio F. Arribas-Cubero3,4, and José G. Villa1 1Department of Physical Education and Sports, Institute of Biomedicine (IBIOMED), University of León, León, Spain 2European University Miguel de Cervantes, Valladolid, Spain 3Castilla y León Mountain Sports, Climbing and Hiking Federation, Valladolid, Spain 4Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain Original scientific paper UDC: 796.61.093.55:612.766.1 Abstract: The aim of this study was to analyze the exercise intensity and competition load (PL) based on heart rate (HR) during different mountain running races. Seven mountain runners participated in this study. They competed in vertical (VR), 10-25 km, 25-45 km and >45 km races. The HR response was measured during the races to calculate the exercise intensity and PL according to the HR at which both the ventilatory (VT) and respiratory compensation threshold (RCT) occurred. The exercise intensity below VT and between VT and RCT increased with mountain running race distance. Likewise, the percentage of racing time spent above RCT decreased when race duration increased. However, the time spent above RCT was similar between races (~50 min). The PL was significantly higher (p<.05) during the longest races (145.0±18.4, 288.8±72.5, 467.3±109.9 and 820.8±147.0 AU in VR, 10-25 km, 25-45 km and >45 km, respectively). The ratio of PL to accumulative altitude gain was similar in all races (~0.16 AU·m-1). -

Xc Ski Racing Plus

XC SKI RACING PLUS XC ski racing is fun… right? Well, what about ski racing with your brain turned on? That’s ski orienteering! What’s the difference? In xc skiing, the course is marked to tell you where to go – just apply the horsepower. In Ski-O, you still have to apply the horsepower, but you have to decide where to go while doing it. How does it work? At the start, you’re given a map of your course, like the map shown here. The pink circles represent control points that you must visit, in the right order, as fast as you can. The solid lines are wide, skateable trails, and dashed lines are narrower trails where you can only double pole. Knowing your relative strength as a skier affects your route choices – how would YOU go from #10 to #11 on this map? What do you do at the controls? At each control, there is a flag to mark the spot. To record that you’ve been there, you “punch” with an electronic recording device, worn on your finger. It makes a beep, and when you finish, the officials download the data from your finger stick and give you instant Equipment: results and your splits between all To carry your map, you use a map holder that mounts to controls. your chest, so that the map is always right in front of you, and can be rotated to align it with the direction you’re skiing. Races are freestyle, so most skiers use race skate skis. Poles are modified to have larger baskets to deal with the soft snow on narrow trails. -

Motorsport News

Motorsport News International Edition – April 2019 Romania FUCHS sponsors Valentin Dobre in 2019 Under Managing Director Camelia Popa, FUCHS Romania joins Valentin Dobre in the Romania Hill Climb Championship. These very popular races attract numerous visitors and are broadcast by Romanian Television. // Page 3. Portugal FUCHS develops a new partnership with Teodósio Motorsport team Ricardo Teodósio and co-driver José Teixeira of the Teodósio Motorsport team represent FUCHS in the Portugal Rally Championship with a Škoda Fabia R5. The Teodósio team win their first race of the PRC, followed by three stage podiums in the FIA ERC, proving themselves worthy competitors and claiming the 2019 title. // Page 7. Spain FUCHS official partner of Yamaha R1 Cup Mario Castillejo, FUCHS Automotive Director, signs a sponsorship deal with Yamaha Motor Sport for the second edition of the Yamaha R1 Cup. In this series 23 drivers compete in six races on the most renowned tracks in Spain; a great business strategy for FUCHS. // Page 12. www.fuchs.com/group Motorsport News International Edition – April 2019 South Africa Scribante succeeds at Zwartkops Coming off a disappointing second round of the G&H Transport Series race in Cape Town, the Franco Scribante Racing team put in some hard work and made a few mechanical tweaks to their Porsche 997 Turbo in preparation for round 3 which took place at Zwartkops Raceway. A rain drenched track didn’t stop FUCHS sponsored Franco Scribante from asserting his dominance, winning round 3 of the Supercar Series. Scribante was quick to demonstrate his intentions in the qualifying race, claiming pole position. -

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

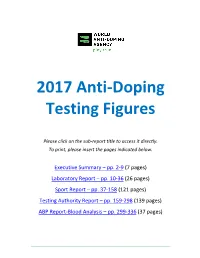

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples). -

Trail Running Guide

Trail Running Guide Martin Brilli & Jukka Puhakka Foreword The purpose of the guide is to work as an introduction to trail running, and raise interest towards the sport. The guide is for both beginners and advanced trail runners. All information provided by the guide is supported by scientific sources. This guide is published in cooperation with Kainuun Liikunta, which organizes multiple mass sport events, including Vuokatti Trail Challenge. The guide includes an introduction of the event and pictures from the previous years, taken by Vaarojen Valokuvaajat. The other pictures used in the guide are taken by the authors, unless mentioned otherwise. The authors of this guide graduated with Bachelor’s Degrees in Sports and Leisure Management from the Kajaani University of Applied Sciences. We hope that you enjoy the guide and wish you enjoyable runs on the trails! Martin & Jukka Table of content 1 What is trail running? 1 2 How to get started? 2 3 Setting up your goals 4 4 Training 5 4.1. Running 6 4.2. Strength training 7 4.3. Training week and periodization 12 5 Nutrition 15 6 Event presentation: Vuokatti Trail Challenge 17 7 References 18 1. What is Trail Running? Trail running is a sport where participants run different distances on trails in nature. According to International Trail Running Association (I-TRA), “trail running is a pedestrian race in a natural environment with minimal possible paved or asphalt road. The amount of roads should not exceed 20% of the distance.”1 However, recreational running on trails also fits in to the definition. -

January/February 1997 Issue $ S .O O NEW ORLEANS TRACK CLUB CONTENTS Established 1963 President’S Report

New Orleans Track Club, January/February 1997 Issue $ s .o o NEW ORLEANS TRACK CLUB CONTENTS Established 1963 President’s Report ...............................................................................................................3 P.O. Box 52003 Editor’s Report ....................................................................................................................3 New Orleans. LA 70152-2003 Executive Director Report ................................................................................................. 3 (504) 482-6682 New Members ....................................................................................................................4 FAX (504) 469-9268 Membership Form .......................................................................................................... 39 [email protected] 1995/1996 Board of Directors Race Results Rick Wilderman NOTC Grand Prix Results................................................................................................15 President • (885-1634) Jackson Day 1 /5/97........................................................................................................... 17 Rick Montgomery Nokia Sugar Bowl’s Mardi Gras Marathon 1/18/97......................................................20 VP/Editor • (833-5074) Jim Garvey Super Bowl/Chinese New Year 1/25/97 ........................................................................ 24 Treasurer • (283-8653) Tour de Parc 2/2/97 ....................................................................................................... -

Calendario Sport Outdoor & Running 2020

CALENDARIO SPORT OUTDOOR & RUNNING 2020 Discipline: outdoor multisport, snow winter trail, skyrunning, trail running, vertical (*) Gare organizzate da ASD associate CSEN/CONI con assicurazione RCT GENNAIO-APRILE *Winter Trail Monte Prealba 52k, Bione (BS) - 4 gennaio *Limone Endurance Race, 6 ore, Limone sul Garda, (BS) - 2 febbraio *Ciaspolada delle Marmarole Trail 43K, Auronzo/Pieve di Cadore (BL) – 8 febbraio *Winter Brich Trail, Valdengo (BI) - 9 febbraio *Fontegno in Corsa 25k e 14k, Cireggio di Omegna (VB) – 9 febbraio Val di Mello Winter Trail, Val Masino (SO) - 9 febbraio Teglio Sunset Winter Trail, Teglio (SO) - 15 febbraio *Winter Snow Trail, Santa Caterina (SO) - 23 febbraio *Memorial Claudio del Favero Vertical, Pieve di Cadore (BL) - 7 marzo *Tarvisio Snow Winter Trail Laghi di Fusine (UD) - 8 marzo Winter Trail dei Castelli – Langhirano (PR) – 8 marzo *Valon Trail, Premero, (VB) – 29 marzo *EcoTrail delle Farfalle, Bordano (UD) - 5 aprile *Colmen Trail, Morbegno (SO) - 12 aprile *Sardinia Skyrunning Experience 21- 42km (VL), Sardegna -12 aprile Allianz Tower, Stair Climb, Milano – 12 aprile *Valzurio Trail, Nasolino (BG) - 25 aprile *Vertical 535incondotta, Moio de Calvi (BG) - 26 aprile MAGGIO *KM Verticale di Cossogno, Cossogno (VB) - 1 maggio *Trofeo Dario & Willy skyrunning 23k, Corni di Canzo, Valmadrera (LC) - 1maggio *Ultra Trail del Mugello, Borgo San Lorenzo (FI) – 2 maggio *Giro Podistico di Pollone, Pollone (BI) – 3 maggio * Lago Maggiore International Trail, Maccagno (VA) - 3 maggio *Trentapassi SkyRace®, Marone (BS) - 3 maggio *Trentapassi Vertical, Marone (BS) - 3 maggio *Mosso Vertical 1000, Valle Mosso (BI) - 10 maggio *JamaRun Trail della valle15 km, Val Rosandra, S. Dorligo - Dolina (TS) - 16 maggio *Val del Riso Trail, Gorno (BG) - 17 maggio *Quattro Passi di Casa Nostra, Sondalo (SO) - 17 maggio *Trail 3 Castelli 50/25/15k - Ultra, Gemona del Friuli (UD) - 17 maggio *Grignone Vertical Extreme – tutt d’un fiàa, Pasturo (LC) - 23 maggio Trofeo P.G. -

March 5-10 • 2018 • USA Welcome from the Craftsbury Outdoor Center

Ski Orienteering World Cup Round 3 World Masters Ski Orienteering Championships Bulletin 1 March 5-10 • 2018 • USA www.craftsbury.com/skio18 Welcome from the Craftsbury Outdoor Center The Town of Craftsbury and the Craftsbury Outdoor Center invite you to attend the March 2018 week of ski-orienteering races. We are excited to host this event in our special part of Vermont and the United States of America. We believe you will find a more friendly, welcoming, and beautiful part of America than you typically see in the media. Over the past 9 years, Craftsbury athletes have enjoyed competing around the world in ski-orienteering competitions. This week of competitions is one way to say thank you to all the people, organizations, and countries that have hosted ski-orienteering in the past. Contents Welcome from the Craftsbury Outdoor Center 2 Organizing Committee 4 Competition Schedule 4 Classes and Participation Restrictions 5 Housing 5 Location, Terrain, and Pre-Training Opportunities 5 Transportation 6 Embargoed Area 6 Embargoed Area Map 6 Doping control 7 Previous orienteering map 8 Organizing Committee Event Director: Adrian Owens Technical Director: Ed Despard Course Setters: Alex Jospe and Andy Hall Contact Website: craftsbury.com/skio18 E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +1 802.289.2890 Paper Mail: Adrian Owens 400 Post Rd Craftsbury Common, VT 05827 Controllers National Event Controller: Ken Walker, Sr (USA) IOF Event Advisor: Staffan Tunis (FIN) IOF Senior Event Advisor: Antti Myllärinen (FIN) Competition Schedule Date World Cup World -

The Hammpions

2019 Relay Team Profile: The Hammpions For two brothers from a family that loves running, the opportunity has finally arrived to team up as a duo for a popular long-distance relay race. Later this month, John and Paul Crowe will run the 50 miles of the Tussey mOUnTaiNBACK 50 Mile Relay and Ultramarathon as a two-person relay team. Both grew up in State College. John Crowe now lives in Pittsburgh and Paul Crowe lives in Milford, NJ. “This is our first time doing the Mountainback,” said John Crowe. “Our dad has always been involved in some capacity, whether hosting runners or competing on teams, so it has always been on our radar.” It’s pretty well known in the local running community that Crowes are not the type to shrink from a challenge. Their father, Rob Crowe, has run numerous races over the years, including the Boston Marathon, and still actively races in the local community. Their mother, Sue, was a standout runner, including multiple wins at the Nittany Valley Arts Festival race. But this kind of race is often out of bounds for students who run for cross country or track teams. “Unfortunately we never had the opportunity to participate in it while we were in high school and college,” said John Crowe. “Now that we are both trying to get back into running competitively again, this seemed like the perfect race to do together.” The course’s 12 segments on the roads of Rothrock State Forest are of unequal length and difficulty, so when these two runners switch back and forth to run every other segment, one will run a total of about 22 and the other about 28 miles.