Je Ne Parle Pas Français”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 6 6-1-2001 (Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art Robert Neustadt Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the American Literature Commons, Latin American Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Neustadt, Robert (2001) "(Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art ," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 25: Iss. 2, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.1510 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art Abstract Masks serve as particularly effective props in contemporary Mexican and Chicano performance art because of a number of deeply rooted traditions in Mexican culture. This essay explores the mask as code of honor in Mexican culture, and foregrounds the manner in which a number of contemporary Mexican and Chicano artists and performers strategically employ wrestling masks to (ef)face the mask- like image of Mexican or U.S. nationalism. I apply the label "performance artist" broadly, to include musicians and political figures that integrate an exaggerated sense of theatricality into their performances. -

Mr and Mrs Dove 1921

MR AND MRS DOVE (1921) By Katherine Mansfield Of course he knew—no man better —that he hadn't a ghost of a chance, he hadn't an earthly. The very idea of such a thing was preposterous. So preposterous that he'd perfectly understand it if her father —well, whatever her father chose to do he'd perfectly understand. In fact, nothing short of desperation, nothing short of the fact that this was positively his last day in England for God knows how long, would have screwed him up to it. And even now... He chose a tie out of the chest of drawers, a blue and cream check tie, and sat on the side of his bed. Supposing she replied, "What impertinence!" would he be surprised? Not in the least, he decided, turning up his soft collar and turning it down over the tie. He expected her to say someth ing like that. He didn't see, if he looked at the affair dead soberly, what else she could say. Here he was! And nervously he tied a bow in front of the mirror, jammed his hair down with both hands, pulled out the flaps of his jacket pockets. Making betwe en 500 and 600 pounds a year on a fruit farm in —of all places—Rhodesia. No capital. Not a penny coming to him. No chance of his income increasing for at least four years. As for looks and all that sort of thing, he was completely out of the running. He cou ldn't even boast of top-hole health, for the East Africa business had knocked him out so thoroughly that he'd had to take six months' leave. -

Appendix: Major Periodical Publications (1910–22)

Appendix: Major Periodical Publications (1910–22) Short stories (signed Katherine Mansfield unless otherwise stated) ‘Bavarian Babies: The Child-Who-Was-Tired’, New Age, 6.17 (24 February 1910), 396–8 [Katharine Mansfield] ‘Germans at Meat’, New Age, 6.18 (3 March 1910), 419–20 [Katharine Mansfield] ‘The Baron’, New Age, 6.19 (10 March 1910), 444 [Katharine Mansfield] ‘The Luft Bad’, New Age, 6.21 (24 March 1910), 493 [Katharine Mansfield] ‘Mary’, Idler, 36.90 (March 1910), 661–5 [K. Mansfield] ‘At “Lehmann’s” ’, New Age, 7.10 (7 July 1910), 225–7 [Katharine Mansfield] ‘Frau Brechenmacher Attends a Wedding’, New Age, 7.12 (21 July 1910), 273–5 ‘The Sister of the Baroness’, New Age, 7.14 (4 August 1910), 323–4 ‘Frau Fischer’, New Age, 7.16 (18 August 1910), 366–8 ‘A Fairy Story’, Open Window, 1.3 (December 1910), 162–76 [Katharina Mansfield] ‘A Birthday’, New Age, 9.3 (18 May 1911), 61–3 ‘The Modern Soul’, New Age, 9.8 (22 June 1911), 183–6 ‘The Journey to Bruges’, New Age, 9.17 (24 August 1911), 401–2 ‘Being a Truthful Adventure’, New Age, 9.19 (7 September 1911), 450–2 ‘A Marriage of Passion’, New Age, 10.19 (7 March 1912), 447–8 ‘Pastiche: At the Club’, New Age, 10.19 (7 March 1912), 449–50 ‘The Woman at the Store’, Rhythm, no. 4 (Spring 1912), 7–24 ‘Pastiche: Puzzle: Find the Book’, New Age, 11.7 (13 June 1912), 165 ‘Pastiche: Green Goggles’, New Age, 11.10 (4 July 1912), 237 ‘Tales of a Courtyard’, Rhythm, no. -

Modernism Reloaded: the Fiction of Katherine Mansfield

DAVID TROTTER Modernism Reloaded: The Fiction of Katherine Mansfield It’s very largely as a Modernist that we now know Katherine Mansfield. Successive waves of new emphasis in the study of literary Modernism have brought her work ever closer to the centre of current understandings of how, when, where, and why this decisive movement arose, and of what it can be said to have accomplished at its most radical. Gender and sexual politics, the interaction of metropolis and colony, periodical networks: whichever way you look, the new emphasis fits.1 No wonder Mansfield has recently been hailed as Modernism’s “most iconic, most representative writer.”2 The aim of this essay is to bring a further perspective in Modernist studies to bear on Mansfield’s fiction, in order primarily to illuminate the fiction, but also, it may be, the perspective. The one I have in mind is that provided in broad outline by enquiries into the historical sequence which leads from nineteenth- century sciences of energy to twentieth-century sciences of information. Introducing an important collection of essays on the topic, Bruce Clarke and Linda Dalrymple Henderson explain that the invention of the steam engine at the beginning of the nineteenth century resulted both in the technological reorganization of industry and transport, and in a new research emphasis on the mechanics of heat. 1 Respectively, Sydney Janet Kaplan, Katherine Mansfield and the Origins of Modernist Fiction (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991); Elleke Boehmer, “Mansfield as Colonial Modernist: Difference Within,” in Gerry Kimber and Janet Wilson, eds, Celebrating Katherine Mansfield: A Centenary Volume of Essays (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 57-71; and Jenny McDonnell, Katherine Mansfield and the Modernist Marketplace: At the Mercy of the Public (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). -

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible. -

Dread Standard, PDF Version Layout Done with Adobe® Indesign® CS 3 on Mac OS X, Using the Typefaces Attic and Book Antiqua

Dread TID002 Table of Contents Chapter 1: To Begin With . 3 Chapter 2: Briefly, the Rules . 6 . Chapter 3: A Question of Character . 16 Chapter 4: How to Host a Dread Game . .28 . Chapter 5: How to Create a Dread Game . 38 . Chapter 6: The Suspenseful Game . 50 Chapter 7: The Supernatural Game . 53 . Chapter 8: The Mad Game . 56 . Chapter 9: The Moral Game . 59 Chapter 10: The Mysterious Game . 62 Chapter 11: The Gory Game . 65. Appendix: Alternate Methods . 68 Story: Beneath the Full Moon . 70 Story: Beneath a Metal Sky . 82 Story: Beneath the Mask . 89 . Dread is a horror game . There is no reason that the content of any game of Dread need be any more horrifying than you wish it to be, and therefore Dread can be suitable for nearly any age . However, the contents of this book delve into mature topics at points, in order to facilitate groups who enjoy those sorts of horror, so please exercise discretion when passing this book around . In par- ticular, Chapter 11 is not suitable for our younger players . For Leslie Scott . original concept by Epidiah Ravachol and woodelf development by The Impossible Dream writing by Epidiah Ravachol editing and additional writing by The Impossible Dream copy editing by Jere Foley layout and cover design by woodelf back cover illustration by Christy Schaefer illustrations on pages 13, 20, 35, 38, 49, 51, 57 by Taylor Winder illustrations on pages 7, 15, 28, 31, 45, 53, 60, 62, 63, 65, 66, 67, 69 by Jill Krynicki Dread Standard, PDF version Layout done with Adobe® InDesign® CS 3 on Mac OS X, using the typefaces Attic and Book Antiqua. -

The Dramatic World Harol I Pinter

THE DRAMATIC WORLD HAROL I PINTER RITUAL Katherine H. Bnrkman $8.00 THE DRAMATIC WORLD OF HAROLD PINTER By Katherine H. Burkman The drama of Harold Pinter evolves in an atmosphere of mystery in which the surfaces of life are realistically detailed but the pat terns that underlie them remain obscure. De spite the vivid naturalism of his dialogue, his characters often behave more like figures in a dream than like persons with whom one can easily identify. Pinter has on one occasion admitted that, if pressed, he would define his art as realistic but would not describe what he does as realism. Here he points to what his audience has often sensed is distinctive in his style: its mixture of the real and sur real, its exact portrayal of life on the surface, and its powerful evocation of that life that lies beneath the surface. Mrs. Burkman rejects the contention of some Pinter critics that the playwright seeks to mystify and puzzle his audience. To the contrary, she argues, he is exploring experi ence at levels that are mysterious, and is a poetic rather than a problem-solving play wright. The poetic images of the play, more over, Mrs. Burkman contends, are based in ritual; and just as the ancient Greeks at tempted to understand the mysteries of life by drawing upon the most primitive of reli gious rites, so Pinter employs ritual in his drama for his own tragicomic purposes. Mrs. Burkman explores two distinct kinds of ritual that Pinter develops in counter point. His plays abound in those daily habit ual activities that have become formalized as ritual and have tended to become empty of meaning, but these automatic activities are set in contrast with sacrificial rites that are loaded with meaning, and force the charac ters to a painful awareness of life from which their daily routines have served to protect them. -

Sin City Hc01. Een Wreed Vaarwel Gratis Epub, Ebook

SIN CITY HC01. EEN WREED VAARWEL GRATIS Auteur: Frank Miller Aantal pagina's: 208 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: none Uitgever: none EAN: 9788868738990 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Sin City NL HC 01 Een wreed vaarwel Het album is een éénmalige uitgave en is verrijkt met een 16 paginatellend dossier met schetsen, scenario's, foto's en andere achtergond informatie over het totstand komen van dit verhaal. Deel 9 in de reeks Biebel De Stroken. De kaalhoofdige stripkleuter Biebel beleeft met zijn vriendje Reggie de meest absurde avonturen. In deze mooi uitgevoerde strokenreeks verschijnen de gags voor het eerst in kleur én eindelijk helemaal compleet. Foltering zal hun deel worden in zijn verrotte gevangenis. Het vierde deel van het magistrale meesterwerk, gebaseerd op de roman van de bekende Duitse fantasy-auteur Wolfgang Hohlbein. Op een ochtend in Galileo ziet een oude Joodse visser vol verbijstering hoe zijn zoons alles in het werk stellen om een zekere Jezus van Nazareth te volgen. Hij besluit om alles te doen om zijn kroost te vinden en ze terug te brengen. Al snel vergezellen andere vaders hem op deze tocht. Een prachtig album dat leest als een roadmovie. WAW Dat is natuurlijk normaal voor een stuntvrouw. Een klein vissersdorpje in het uiterste zuiden van Italië is het toneel van een nieuw avontuur: een jonge vrouw wordt verdronken teruggevonden, een Engelse heer is stomdronken op alle uren van de dag, er zijn vier schijnbaar zachtmoedige karakters en onuitstaanbare tweelingen. Mauro Caldi gaat, in een prachtige Jaguar XK, op onderzoek uit op Daarnaast een kort verhaal over het leven van Sigmar Rhone, één van de machtigste leden van de Trust. -

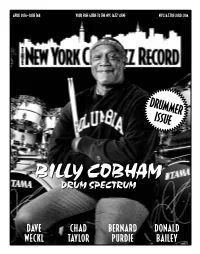

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step. -

Shedding the Mask: Using the Literature of the Civil Rights Era to Reveal the Motivations of the Movement

Shedding the Mask: Using the Literature of the Civil Rights Era to Reveal the Motivations of the Movement Emily Williams Introduction This is a unit for students in my Advanced Placement United States Government and Politics class that examines the transition of thought that occurred in the African American community from the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement through the 1970s. The students in AP Government are seniors who have already completed studies on the civil rights movement in the AP class as well as their US History and Civics and Economics classes. The Civil Rights Era in America is a topic that students enjoy studying. They are drawn to the themes of alienation and oppression. I believe students relate strongly to these themes because, as teenagers, they see their lives as lacking in certain freedoms: adults control how they spend much of their time, they are often not able to make decisions for themselves, and they must often hide who they are to please the people around them. It is this last point that will be the center of my unit. I want students to understand more than the important people, events, and dates of the Civil Rights Movement that are studied in the Advanced Placement Government curriculum. I want them to understand the motivations of the people involved in the movement, and reading the literature of the era will provide that opportunity. African-American culture is rich with literature and music that chronicles what it is like to be marginalized in society. Unfortunately, students explore very little of this literature in school. -

Чик Кñšñ€Ð¸ÑÐлбуð¼

Чик ÐšÑŠÑ€Ð¸Ñ ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) Circulus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/circulus-5121711/songs Circling In https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/circling-in-5121542/songs The Complete "Is" Sessions https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-complete-%22is%22-sessions-7727091/songs Touchstone https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/touchstone-7828728/songs The Vigil https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-vigil-17030425/songs Children's Songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/children%27s-songs-5098223/songs Inner Space https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/inner-space-6035581/songs Expressions https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/expressions-5421714/songs Rendezvous in New York https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/rendezvous-in-new-york-7312835/songs Delphi II & III https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/delphi-ii-%26-iii-5254403/songs Trio Music https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/trio-music-7843087/songs Alive https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/alive-4727412/songs Three Quartets https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/three-quartets-7797708/songs Forever https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/forever-28452035/songs Time Warp https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/time-warp-17034175/songs The Chick Corea Elektric Band https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-chick-corea-elektric-band-3986254/songs Tap Step https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/tap-step-7684375/songs Beneath the -

The Garden Party

The Garden Party by Katherine Mansfield 图书在版编目(CIP)数据 The Garden Party /杨丹主编 飞天电子音像出版社 2004 ISBN 7-900363-43-2 监 王 出版发行 飞天电子音像出版社 责任编辑 杨丹 经销 全国各地新华书店 印刷 北京施园印刷厂 版次 2004年6月第1版 书号 ISBN 7-900363-43-2 CONTENTS 1. AT THE BAY................................................................................... 1 2. THE GARDEN PARTY.................................................................... 80 3. THE DAUGHTERS OF THE LATE COLONEL. ......................... 112 4. MR. AND MRS. DOVE. ................................................................ 158 5. THE YOUNG GIRL....................................................................... 176 6. LIFE OF MA PARKER. ................................................................. 189 7. MARRIAGE A LA MODE............................................................. 203 8. THE VOYAGE. .............................................................................. 226 9. MISS BRILL. ................................................................................. 244 10. HER FIRST BALL. ...................................................................... 255 11. THE SINGING LESSON. ............................................................ 269 12. THE STRANGER ........................................................................ 281 13. BANK HOLIDAY......................................................................... 308 14. AN IDEAL FAMILY..................................................................... 315 15. THE LADY'S-MAID...................................................................