“I Is Another”: in Search of Bob Dylan's Many Masks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 6 6-1-2001 (Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art Robert Neustadt Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the American Literature Commons, Latin American Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Neustadt, Robert (2001) "(Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art ," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 25: Iss. 2, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.1510 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art Abstract Masks serve as particularly effective props in contemporary Mexican and Chicano performance art because of a number of deeply rooted traditions in Mexican culture. This essay explores the mask as code of honor in Mexican culture, and foregrounds the manner in which a number of contemporary Mexican and Chicano artists and performers strategically employ wrestling masks to (ef)face the mask- like image of Mexican or U.S. nationalism. I apply the label "performance artist" broadly, to include musicians and political figures that integrate an exaggerated sense of theatricality into their performances. -

Bob Dylan: the 30 Th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’S Great Performances in March

Press Contact: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Press materials; http://pressroom.pbs.org/ or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom/ Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS “Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’s Great Performances in March A veritable Who’s Who of the music scene includes Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, Neil Young, Kris Kristofferson, Tom Petty, Tracy Chapman, George Harrison and others Great Performances presents a special encore of highlights from 1992’s star-studded concert tribute to the American pop music icon at New York City’s Madison Square Garden in Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration in March on PBS (check local listings). (In New York, THIRTEEN will air the concert on Friday, March 7 at 9 p.m.) Selling out 18,200 seats in a frantic, record-breaking 70 minutes, the concert gathered an amazing Who’s Who of performers to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the enigmatic singer- songwriter’s groundbreaking debut album from 1962, Bob Dylan . Taking viewers from front row center to back stage, the special captures all the excitement of this historic, once-in-a-lifetime concert as many of the greatest names in popular music—including The Band , Mary Chapin Carpenter , Roseanne Cash , Eric Clapton , Shawn Colvin , George Harrison , Richie Havens , Roger McGuinn , John Mellencamp , Tom Petty , Stevie Wonder , Eddie Vedder , Ron Wood , Neil Young , and more—pay homage to Dylan and the songs that made him a legend. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia KOUVAROU, MARIA How to cite: KOUVAROU, MARIA (2011) `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1391/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Maria Kouvarou MA by Research in Musicology Music Department Durham University 2011 Maria Kouvarou ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Abstract Bob Dylan’s work has frequently been the object of discussion, debate and scholarly research. It has been commented on in terms of interpretation of the lyrics of his songs, of their musical treatment, and of the distinctiveness of Dylan’s performance style, while Dylan himself has been treated both as an important figure in the world of popular music, and also as an artist, as a significant poet. -

13-Inside Front-Back Pages.Qxd

STATE OF NEW YORK COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT For Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2003 Prepared by the Office of the State Comptroller Alan G. Hevesi _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 2 • STATE OF NEW YORK Contents INTRODUCTORY SECTION Letter from the Comptroller . 7 Financial Overview . 9 Certificate of Achievement . 12 New York State Organization Chart . 13 Selected State Officials . 13 FINANCIAL SECTION Independent Auditors’ Report . 16 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS . 19 BASIC FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Statement of Net Assets . 31 Statement of Activities . 32 Balance Sheet—Governmental Funds . 34 Reconciliation of the Balance Sheet— Governmental Funds to the Statement of Net Assets . 35 Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances (Deficit)—Governmental Funds . 36 Reconciliation of the Statement of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balances—Governmental Funds to the Statement of Activities . 37 Statement of Net Assets—Enterprise Funds . 38 Statement of Revenues, Expenses and Changes in Fund Net Assets— Enterprise Funds . 39 Statement of Cash Flows—Enterprise Funds . 40 Statement of Fiduciary Net Assets—Fiduciary Funds . 42 Statement of Changes in Fiduciary Net Assets—Fiduciary Funds . 43 Combining Statement of Net Assets—Discretely Presented Component Units . 44 Combining Statement of Activities—Discretely Presented Component Units . 46 Notes to the Basic Financial Statements . 49 REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Budgetary Basis—Financial Plan and Actual—Combined Schedule of Cash Receipts and Disbursements—Major Funds— General Fund and Federal Special Revenue Fund . 84 Notes to Required Supplementary Information Budgetary Basis Reporting . 86 Infrastructure Assets Using the Modified Approach . 87 OTHER SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION General Fund Narrative . 91 Combining Schedule of Balance Sheet Accounts . 92 Combining Schedule of Revenues, Expenditures and Changes in Fund Balance (Deficits) Accounts . -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible. -

Snow Over Interstate 80, Un Immaginario Album Di Canzoni Natalizie Registrato Da Bob Dylan a Metà Degli Anni '60

Nel 1975 il New Musical Express pubblicò, per ridere coi propri lettori, la finta recensione di Snow Over Interstate 80, un immaginario album di canzoni natalizie registrato da Bob Dylan a metà degli anni '60. Snow Over Interstate 80 Picture of the spoof 1975 The eventual 2009 'Twas The Night Before album cover from Wim album cover Christmas - 7" single B- van der Mark side [Home] [ Up ] The following spoof article appeared in the UK music magazine "New Musical Express" in 1975. I've included it here not only because it's pretty funny but also because the original list of unreleased Dylan songs that started this project off included three "mystery" names: FREEWHEELIN', NIGHTINGALE'S CODE and WOODSTOCK YULE. Somewhere along the line the fact that these were spoof titles had been lost, so I wanted to set the record straight. Remember, the article below is a hoax! Bob of course released a genuine Christmas album, Christmas In The Heart, in 2009. Alan Fraser DYLAN - the missing Christmas album At last, definite evidence has come to light that confirms that, in the autumn of 1965, Bob Dylan did record a Christmas Album. The existence of the Dylan Christmas Album has always been hotly denied by Dylan himself, his management, and his record company. Even the most determined bootleggers and Dylanologists have been unable to obtain extant copies of the record, the master tapes of which were allegedly destroyed when the project was suddenly nixed by Dylan himself at the eleventh hour. Now, "Thrills" has obtained a copy, rumoured to be one of only seven copies in the world, the other copies being in the possession of Dylan himself, his then manager Albert Grossman, ex-CBS president Clive Davis and an anonymous French collector said to have paid $100,000 for it in 1966. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

Bound for Glory Bob Dylan 1962

BOUND FOR GLORY BOB DYLAN 1962 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, RELEASES, TAPES & BOOKS. © 2001 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Bound For Glory — Bob Dylan 1962 page 2 CONTENTS: 1 INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................... 3 2 YEAR AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................. 3 3 CALENDAR .............................................................................................................................. 3 4 RECORDINGS ......................................................................................................................... 7 5 SONGS 1962 .............................................................................................................................. 7 6 SOURCES .................................................................................................................................. 9 7 SUGGESTED READINGS .................................................................................................... 10 7.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND .................................................................................................... 10 7.2 ARTICLE COMPILATIONS ................................................................................................... -

The 15Th Annual Senior Expo: Better Than Ever!

November 2015 • Vol. 15 • Issue 11 • www.BerksEncore.org For information on advertising in berksencore news please contact 610-374-3195, ext. 227. Inside This Issue... Agency Happenings ....pgs 5 & 6 Anniversaries ....................pg 29 2015 Berks Encore Programs ......pg 18 Center News ..............pgs 19, 22 Combat Veteran Remembers ..pg 28 Discount Program ............... pg 7 brought to you by Dollars & Sense ..... pgs 16 & 17 Law and Order ..........pgs 10~12 On-Going Activities .. pgs 20 & 21 Volunteer Spotlight ............. pg 9 The 15th Annual Senior Expo: Your Agency ........... pgs 24 & 25 Your Community ......pgs 27~38 Your Health ..............pgs 13~15 Better than Ever! Your Technology ................pg 23 Berks Encore’s Senior Expo takes place on tions can also be dropped off at The Body Zone Tuesday, October 27 at the Body Zone Sports & Sports and Wellness Complex the day of the event. Wellness Complex, 3103 Paper Mill Road in Wyo- Center Spotlight .................pg 8 missing. Your possibilities for the day are endless: PRESENTATIONS AND PROGRAMS more than 120 vendors, Medicare counseling and Title sponsor Reading Health System will pro- presentations, cooking demonstrations, fl u shots, vide a variety of health screenings on the basket- educational sessions, and entertainment. ball court. In addition, fl u shots will be provided Senior Expo will be open from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. by Berks Visiting Nurses (please note that there To keep the day running smoothly, Berks Encore may be a $30 fee, payable by cash or check - if the has some logistical instructions and procedures for individual does not have original Medicare A & B all attendees. -

Pdf of TODO Austin November 2017

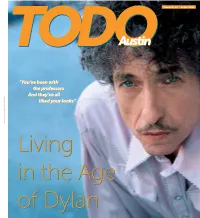

Volume II, 04 August 2010 “You’ve been with thethe professorsprofessors AndAnd they’vethey’ve allall likedliked youryour looks”looks” so many people to thank. In this golden age when American popular culture is a worldwide culture, Bob Dylan is in many ways its fons et origo From Osaka, Japan to Oslo, Norway, from Rio de Janeiro to (its spring and source). “It’s an immense privilege to live at the the Rubber Bowl in Akron, Ohio, from Istanbul to the Isle of same time as this genius,” states British literary critic and former Wight, Dylan has performed his unique distillation of American Oxford Professor of Poetry, Christopher Ricks. musical traditions. His music transcends time and place and On the eve of his August 16th concert date in Austin-a crosses cultural boundaries. Around the world and up and community which has adopted Dylan as one of its own-TODO down Highway 35, Dylan remains the most important artist Austin has invited three American scholars to reflect on Dylan’s alive today, “anywhere and in any field,” to quote England’s wide cultural impact. Poet Laureate, Andrew Motion. One sure sign of Dylan’s influence is that all three scholars, a I had the honor of presenting the key to the City of Austin to noted University of Texas at Austin English professor and poet, Dylan on February 24, 2002, Bob Dylan Day. In our short visit, a UT MacArthur fellow who studies ancient Greek culture and Dylan expressed then to the mayor pro-tem and me how the human response, including song, to war and violence, and a Harvard professor who is the world’s foremost authority happy he was to have been made an honorary Texan by the on the Roman poet Virgil and the later influence of classical previous Governor. -

A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties Online

cifps (Free and download) A Freewheelin' Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties Online [cifps.ebook] A Freewheelin' Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties Pdf Free Par Suze Rotolo ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #368745 dans eBooksPublié le: 2009-09-01Sorti le: 2009-09- 01Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 53.Mb Par Suze Rotolo : A Freewheelin' Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised A Freewheelin' Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles2 internautes sur 2 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. happy sixtiesPar Pam Wellune réflexion sensible et intelligente sur la génération post Kérouac et l'évocation d'un folk bien éloigné du tiroir caisse.A défaut de pouvoir la vivre une joie de la revivre.2 internautes sur 2 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. My Back PagesPar FarRockAwayWhat a time it was, brought instantly back to life with this book. Suze was a straight forward girl who captured her ride on the carousel perfectly. A journey of substance and gravitas which echoes down the memories of time. Read it and experience the moment for it will never come again. Présentation de l'éditeur‘I met Bob Dylan in 1961 when I was seventeen years old and he was twenty…’ Thus begins Suze Rotolo’s wonderfully romantic story of their sweet but sometimes wrenching love affair and its eventual collapse under the pressure of Dylan’s growing fame.