Peter Joyce, the Liberal Party and the Popular Front

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transfer of Power and the Crisis of Dalit Politics in India, 1945–47

Modern Asian Studies 34, 4 (2000), pp. 893–942. 2000 Cambridge University Press Printed in the United Kingdom Transfer of Power and the Crisis of Dalit Politics in India, 1945–47 SEKHAR BANDYOPADHYAY Victoria University of Wellington Introduction Ever since its beginning, organized dalit politics under the leadership of Dr B. R. Ambedkar had been consistently moving away from the Indian National Congress and the Gandhian politics of integration. It was drifting towards an assertion of separate political identity of its own, which in the end was enshrined formally in the new constitu- tion of the All India Scheduled Caste Federation, established in 1942. A textual discursive representation of this sense of alienation may be found in Ambedkar’s book, What Congress and Gandhi Have Done to the Untouchables, published in 1945. Yet, within two years, in July 1947, we find Ambedkar accepting Congress nomination for a seat in the Constituent Assembly. A few months later he was inducted into the first Nehru Cabinet of free India, ostensibly on the basis of a recommendation from Gandhi himself. In January 1950, speaking at a general public meeting in Bombay, organized by the All India Scheduled Castes Federation, he advised the dalits to co- operate with the Congress and to think of their country first, before considering their sectarian interests. But then within a few months again, this alliance broke down over his differences with Congress stalwarts, who, among other things, refused to support him on the Hindu Code Bill. He resigned from the Cabinet in 1951 and in the subsequent general election in 1952, he was defeated in the Bombay parliamentary constituency by a political nonentity, whose only advantage was that he contested on a Congress ticket.1 Ambedkar’s chief election agent, Kamalakant Chitre described this electoral debacle as nothing but a ‘crisis’.2 1 For details, see M. -

Women and the Communist Party of Canada, 1932-1941, with Specific Reference to the Activism of Dorothy Livesay and Jim Watts

Mother Russia and the Socialist Fatherland: Women and the Communist Party of Canada, 1932-1941, with specific reference to the activism of Dorothy Livesay and Jim Watts by Nancy Butler A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada November 2010 Copyright © Nancy Butler, 2010 ii Abstract This dissertation traces a shift in the Communist Party of Canada, from the 1929 to 1935 period of militant class struggle (generally known as the ‘Third Period’) to the 1935-1939 Popular Front Against Fascism, a period in which Communists argued for unity and cooperation with social democrats. The CPC’s appropriation and redeployment of bourgeois gender norms facilitated this shift by bolstering the CPC’s claims to political authority and legitimacy. ‘Woman’ and the gendered interests associated with women—such as peace and prices—became important in the CPC’s war against capitalism. What women represented symbolically, more than who and what women were themselves, became a key element of CPC politics in the Depression decade. Through a close examination of the cultural work of two prominent middle-class female members, Dorothy Livesay, poet, journalist and sometime organizer, and Eugenia (‘Jean’ or ‘Jim’) Watts, reporter, founder of the Theatre of Action, and patron of the Popular Front magazine New Frontier, this thesis utilizes the insights of queer theory, notably those of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Judith Butler, not only to reconstruct both the background and consequences of the CPC’s construction of ‘woman’ in the 1930s, but also to explore the significance of the CPC’s strategic deployment of heteronormative ideas and ideals for these two prominent members of the Party. -

Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM AND AFRICAN AND CARIBBEAN INTELLECTUALS IN LONDON, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Bonnie G. Smith And approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean Intellectuals in London, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA Dissertation Director: Bonnie G. Smith During the three decades between the end of World War I and 1950, African and West Indian scholars, professionals, university students, artists, and political activists in London forged new conceptions of community, reshaped public debates about the nature and goals of British colonialism, and prepared the way for a revolutionary and self-consciously modern African culture. Black intellectuals formed organizations that became homes away from home and centers of cultural mixture and intellectual debate, and launched publications that served as new means of voicing social commentary and political dissent. These black associations developed within an atmosphere characterized by a variety of internationalisms, including pan-ethnic movements, feminism, communism, and the socialist internationalism ascendant within the British Left after World War I. The intellectual and political context of London and the types of sociability that these groups fostered gave rise to a range of black internationalist activity and new regional imaginaries in the form of a West Indian Federation and a United West Africa that shaped the goals of anticolonialism before 1950. -

50 Douglas Liberal Predicament

THE LIBERAL PREDICAMENT, 1945 – 64 For most of the twenty years from 1945 to 1964, it looked as if the Liberals were finished. They were reduced to a handful of MPs, most of whom held their seats precariously,. They were desperately short of money and organisation, and were confronted by two great parties, both seeking to look as ‘liberal’ as possible. For the ambitious would- be Liberal politician, there was practically no prospect of a seat in Parliament, or even on the local council. Roy Douglas examines why, despite the desperate state of their party, many Liberals kept the faith going, and not only carried on campaigning, but also laid the foundations for long-term revival. Liberal election poster, 196 1 Journal of Liberal History 50 Spring 2006 THE LIBERAL PREDICAMENT, 1945 – 64 he great Liberal vic- It wasn’t at all like 1874, when a failed. At the general election of tory of 1906 had been Liberal government had more or that year, the Liberal Party won won, more than any- less worked itself out of a job, or a little under 5.3 million votes, thing else, by the party’s 1886, when a Liberal government against well over 8 million each devotion to free trade was divided on a major issue of for the other two parties; but Tand its resistance both to the policy, or 1895, when a Liberal they only obtained fifty-nine protectionist campaign of ren- government collapsed in chaos. MPs, one of whom promptly egade Joseph Chamberlain and Wisely or (to the author’s mind) defected to Labour. -

The Popular Front: Roadblock to Revolution

Internationalist Group League for th,e Fourth International The Popular Front: Roadblock to Revolution Volunteers from the anarcho-syndicalist CNT and POUM militias head to the front against Franco's forces in Spanish Civil War, Barcelona, September 1936. The bourgeois Popular Front government defended capitalist property, dissolved workers' militias and blocked the road to revolution. Internationalist Group Class Readings May 2007 $2 ® <f$l~ 1162-M Introduction The question of the popular front is one of the defining issues in our epoch that sharply counterpose the revolution ary Marxism of Leon Trotsky to the opportunist maneuverings of the Stalinists and social democrats. Consequently, study of the popular front is indispensable for all those who seek to play a role in sweeping away capitalism - a system that has brought with it untold poverty, racial, ethnic, national and sexual oppression and endless war - and opening the road to a socialist future. "In sum, the People's Front is a bloc of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat," Trotsky wrote in December 1937 in re sponse to questions from the French magazine Marianne. Trotsky noted: "When two forces tend in opposite directions, the diagonal of the parallelogram approaches zero. This is exactly the graphic formula of a People's Front govern ment." As a bloc, a political coalition, the popular (or people's) front is not merely a matter of policy, but of organization. Opportunists regularly pursue class-collaborationist policies, tailing after one or another bourgeois or petty-bourgeois force. But it is in moments of crisis or acute struggle that they find it necessary to organizationally chain the working class and other oppressed groups to the class enemy (or a sector of it). -

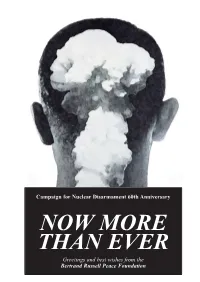

The Beginning Since Atomic Weapons Were First Used in 1945 It Is Odd That There Was No Big Campaign Against Them Until 1957

13.RussellCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:47 Page 14 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament 60th Anniversary NOW MORE THAN EVER Greetings and best wishes from the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation 14.DuffCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:48 Page 9 93 The Beginning Since atomic weapons were first used in 1945 it is odd that there was no big campaign against them until 1957. There CND 195865 had been one earlier attempt at a campaign, in 1954, when Britain was proceeding to make her own HBombs. Fourteen years later, Anthony Wedgwood Benn, who was one who led the Anti HBomb Petition then, was refusing the CND Aldermaston marchers permission to stop and hold a meeting on ministry land, outside the factory near Burghfield, Berks, making, warheads for Polaris submarine missiles. Autres temps, autres moeurs. Peggy Duff There were two reasons why it suddenly zoomed up in 1957.The first stimulus was the HBomb tests at Christmas Island in the Pacific. It was these that translated the committee formed in Hampstead in North London into a national campaign, and which brought into being a number of local committees around Britain which predated CND itself — in Oxford, in Reading, in Kings Lynn and a number of other places. Tests were a constant and very present reminder of the menace of nuclear weapons, affecting especially the health of children, and of babies yet unborn. Fallout seemed something uncanny, unseen and frightening. The Christmas Island tests, because they were British tests, at last roused opinion in Britain. The second reason was the failure of the Labour Party in the autumn of 1957 to pass, Peggy Duff was the first as expected, a resolution in favour of secretary of the Campaign unilateral abandonment of nuclear weapons for Nuclear Disarmament. -

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 a Thesis Submitted to the University of Manches

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 David W. Mottram School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of contents Abstract p.4 Declaration p.5 Copyright statement p.5 Acknowledgements p.6 Introduction p.7 Terminology, sources and methods p.10 Structure of the thesis p.14 Chapter One The Lost War p.16 1.1 The place of ‘Spain’ in British politics p.17 1.2 Viewing ‘Spain’ through external perspectives p.21 1.3 The dispersal, 1939 p.26 Conclusion p.31 Chapter Two Adjustments to the Lost War p.33 2.1 The Communist Party and the International Brigaders: debt of honour p.34 2.2 Labour’s response: ‘The Spanish agitation had become history’ p.43 2.3 Decline in public and political discourse p.48 2.4 The political parties: three Spanish threads p.53 2.5 The personal price of the lost war p.59 Conclusion p.67 2 Chapter Three The lessons of ‘Spain’: Tom Wintringham, guerrilla fighting, and the British war effort p.69 3.1 Wintringham’s opportunity, 1937-1940 p.71 3.2 ‘The British Left’s best-known military expert’ p.75 3.3 Platform for influence p.79 3.4 Defending Britain, 1940-41 p.82 3.5 India, 1942 p.94 3.6 European liberation, 1941-1944 p.98 Conclusion p.104 Chapter Four The political and humanitarian response of Clement Attlee p.105 4.1 Attlee and policy on Spain p.107 4.2 Attlee and the Spanish Republican diaspora p.113 4.3 The signal was Greece p.119 Conclusion p.125 Conclusion p.127 Bibliography p.133 49,910 words 3 Abstract Complexities and divisions over British left-wing responses to the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939 have been well-documented and much studied. -

Sir Richard Acland Et Le Parti Common Wealth Au Cours De La Deuxième Guerre Mondiale

Cercles 11 (2004) LE DERNIER AVATAR DE LA NOTION DE COMMONWEALTH ? Sir Richard Acland et le parti Common Wealth au cours de la deuxième Guerre mondiale ANTOINE CAPET Université de Rouen Avant tout, il convient peut-être de présenter Sir Richard Acland (1906-1990).1 Issu d’une vieille famille de propriétaires terriens du Devon, son grand-père avait été ministre sous Gladstone, et il fut élu député libéral du North Devon en 1935. À la mort de son père quelques mois plus tard, il hérita du domaine foncier familial et du titre de baronet — d’où le Sir de Sir Richard Acland — mais, conformément à ses idéaux égalitaires, il légua toutes ses terres au National Trust en 1943. La virulence de ses prises de position anti-fascistes et anti-apaisement le conduira dans les années 1938-1939 à être en rupture de ban avec son parti, et le tournant de Dunkerque en mai-juin 1940 lui donnera la chance qu’il attendait de « régénérer » la Grande- Bretagne. Le rapprochement qu’il effectue alors avec certains intellectuels de la gauche non travailliste et non communiste aboutira à la création en 1941 du mouvement Forward March, qui fusionnera en 1942 avec le 1941 Committee pour former le parti Common Wealth.2 Avant de parler du parti lui-même, il convient peut-être de faire un petit peu, non pas de philosophie, mais de philologie, et avant d’aborder l’histoire des idées, il convient peut-être de faire un petit peu d’histoire de la langue. Le nom retenu pour le nouveau parti n’est en effet pas anodin. -

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 To the Chancellors and Vice-Chancellors of the University of Bristol past, present and future Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU © David Cannadine 2016 All rights reserved This text was first published by the University of Bristol in 2015. First published in print by the Institute of Historical Research in 2016. This PDF edition published in 2017. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 18 6 (paperback edition) ISBN 978 1 909646 64 3 (PDF edition) I never had the advantage of a university education. Winston Churchill, speech on accepting an honorary degree at the University of Copenhagen, 10 October 1950 The privilege of a university education is a great one; the more widely it is extended the better for any country. Winston Churchill, Foundation Day Speech, University of London, 18 November 1948 I always enjoy coming to Bristol and performing my part in this ceremony, so dignified and so solemn, and yet so inspiring and reverent. Winston Churchill, Chancellor’s address, University of Bristol, 26 November 1954 Contents Preface ix List of abbreviations xi List of illustrations xiii Introduction 1 1. -

J\S-Aacj\ Cwton "Wallop., $ Bl Sari Of1{Ports Matd/I

:>- S' Ui-cfAarria, .tffzatirU&r- J\s-aacj\ cwton "Wallop., $ bL Sari of1 {Ports matd/i y^CiJixtkcr- ph JC. THE WALLOP FAMILY y4nd Their Ancestry By VERNON JAMES WATNEY nATF MICROFILMED iTEld #_fe - PROJECT and G. S ROLL * CALL # Kjyb&iDey- , ' VOL. 1 WALLOP — COLE 1/7 OXFORD PRINTED BY JOHN JOHNSON Printer to the University 1928 GENEALOGirA! DEPARTMENT CHURCH ••.;••• P-. .go CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Omnes, si ad originem primam revocantur, a dis sunt. SENECA, Epist. xliv. One hundred copies of this work have been printed. PREFACE '•"^AN these bones live ? . and the breath came into them, and they ^-^ lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.' The question, that was asked in Ezekiel's vision, seems to have been answered satisfactorily ; but it is no easy matter to breathe life into the dry bones of more than a thousand pedigrees : for not many of us are interested in the genealogies of others ; though indeed to those few such an interest is a living thing. Several of the following pedigrees are to be found among the most ancient of authenticated genealogical records : almost all of them have been derived from accepted and standard works ; and the most modern authorities have been consulted ; while many pedigrees, that seemed to be doubtful, have been omitted. Their special interest is to be found in the fact that (with the exception of some of those whose names are recorded in the Wallop pedigree, including Sir John Wallop, K.G., who ' walloped' the French in 1515) every person, whose lineage is shown, is a direct (not a collateral) ancestor of a family, whose continuous descent can be traced since the thirteenth century, and whose name is identical with that part of England in which its members have held land for more than seven hundred and fifty years. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

The Sheffield peace movement 1934-1940. STEVENSON, David Anthony Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/3916/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/3916/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10701051 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10701051 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 The Sheffield Peace Movement 1934 -1940 David Anthony Stevenson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2001 Abstract: The object of the thesis was to build a portrait of a local peace movement in order to contrast and compare it with existing descriptions of the peace movement written from a national perspective. -

The University of Arizona

Erskine Caldwell, Margaret Bourke- White, and the Popular Front (Moscow 1941) Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Caldwell, Jay E. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 10:56:28 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/316913 ERSKINE CALDWELL, MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE, AND THE POPULAR FRONT (MOSCOW 1941) by Jay E. Caldwell __________________________ Copyright © Jay E. Caldwell 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Jay E. Caldwell, titled “Erskine Caldwell, Margaret Bourke-White, and the Popular Front (Moscow 1941),” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Dissertation Director: Jerrold E. Hogle _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Daniel F. Cooper Alarcon _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Jennifer L. Jenkins _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Robert L. McDonald _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11 February 2014 Charles W. Scruggs Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College.