Accepted Manuscript, Lovell, the Common Wealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas a Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill As a Liberal J

Journal of Issue 25 / Winter 1999–2000 / £5.00 Liberal DemocratHISTORY Crossing the Floor Roy Douglas A Failure of Leadership Liberal Defections 1918–29 Senator Jerry Grafstein Winston Churchill as a Liberal J. Graham Jones A Breach in the Family Megan and Gwilym Lloyd George Nick Cott The Case of the Liberal Nationals A re-evaluation Robert Maclennan MP Breaking the Mould? The SDP Liberal Democrat History Group Issue 25: Winter 1999–2000 Journal of Liberal Democrat History Political Defections Special issue: Political Defections The Journal of Liberal Democrat History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group 3 Crossing the floor ISSN 1463-6557 Graham Lippiatt Liberal Democrat History Group Editorial The Liberal Democrat History Group promotes the discussion and research of 5 Out from under the umbrella historical topics, particularly those relating to the histories of the Liberal Democrats, Liberal Tony Little Party and the SDP. The Group organises The defection of the Liberal Unionists discussion meetings and publishes the Journal and other occasional publications. 15 Winston Churchill as a Liberal For more information, including details of publications, back issues of the Journal, tape Senator Jerry S. Grafstein records of meetings and archive and other Churchill’s career in the Liberal Party research sources, see our web site: www.dbrack.dircon.co.uk/ldhg. 18 A failure of leadership Hon President: Earl Russell. Chair: Graham Lippiatt. Roy Douglas Liberal defections 1918–29 Editorial/Correspondence Contributions to the Journal – letters, 24 Tory cuckoos in the Liberal nest? articles, and book reviews – are invited. The Journal is a refereed publication; all articles Nick Cott submitted will be reviewed. -

Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM AND AFRICAN AND CARIBBEAN INTELLECTUALS IN LONDON, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Bonnie G. Smith And approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean Intellectuals in London, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA Dissertation Director: Bonnie G. Smith During the three decades between the end of World War I and 1950, African and West Indian scholars, professionals, university students, artists, and political activists in London forged new conceptions of community, reshaped public debates about the nature and goals of British colonialism, and prepared the way for a revolutionary and self-consciously modern African culture. Black intellectuals formed organizations that became homes away from home and centers of cultural mixture and intellectual debate, and launched publications that served as new means of voicing social commentary and political dissent. These black associations developed within an atmosphere characterized by a variety of internationalisms, including pan-ethnic movements, feminism, communism, and the socialist internationalism ascendant within the British Left after World War I. The intellectual and political context of London and the types of sociability that these groups fostered gave rise to a range of black internationalist activity and new regional imaginaries in the form of a West Indian Federation and a United West Africa that shaped the goals of anticolonialism before 1950. -

Education and Politics in the British Armed Forces in the Second World War*

PENELOPE SUMMERFIELD EDUCATION AND POLITICS IN THE BRITISH ARMED FORCES IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR* Several eminent Conservatives, including Winston Churchill, believed that wartime schemes of education in the Armed Forces caused servicemen to vote Labour at the Election of 1945. For instance, R. A. Butler wrote: "The Forces' vote in particular had been virtually won over by the left- wing influence of the Army Bureau of Current Affairs."1 So frequently was this view stated that ABCA became a scapegoat for Tory defeat.2 By no means all servicemen voted. 64% put their names on a special Service Register in November 1944, and 37% (just over half of those who registered) actually voted by post or proxy in July 1945, a total of 1,701,000. Research into the Election in the soldiers' home constituencies, where their votes were recorded, suggests that they made little difference to the outcome of the election.3 But the Tories' assumption that servicemen voted Labour is borne out. McCallum and Readman indicate that their vote confirmed, though it did not cause, the swing to Labour in the con- stituencies, and those with memories of the separate count made of the servicemen's ballot papers recall that it was overwhelmingly left-wing, e.g., Labour in the case of Reading, where Ian Mikardo was candidate.4 * I should like to thank all those who were kind enough to talk to me about their experiences on active service or in the War Office, some of which have been quoted, but all of which have been helpful in writing this paper. -

The Beginning Since Atomic Weapons Were First Used in 1945 It Is Odd That There Was No Big Campaign Against Them Until 1957

13.RussellCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:47 Page 14 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament 60th Anniversary NOW MORE THAN EVER Greetings and best wishes from the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation 14.DuffCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:48 Page 9 93 The Beginning Since atomic weapons were first used in 1945 it is odd that there was no big campaign against them until 1957. There CND 195865 had been one earlier attempt at a campaign, in 1954, when Britain was proceeding to make her own HBombs. Fourteen years later, Anthony Wedgwood Benn, who was one who led the Anti HBomb Petition then, was refusing the CND Aldermaston marchers permission to stop and hold a meeting on ministry land, outside the factory near Burghfield, Berks, making, warheads for Polaris submarine missiles. Autres temps, autres moeurs. Peggy Duff There were two reasons why it suddenly zoomed up in 1957.The first stimulus was the HBomb tests at Christmas Island in the Pacific. It was these that translated the committee formed in Hampstead in North London into a national campaign, and which brought into being a number of local committees around Britain which predated CND itself — in Oxford, in Reading, in Kings Lynn and a number of other places. Tests were a constant and very present reminder of the menace of nuclear weapons, affecting especially the health of children, and of babies yet unborn. Fallout seemed something uncanny, unseen and frightening. The Christmas Island tests, because they were British tests, at last roused opinion in Britain. The second reason was the failure of the Labour Party in the autumn of 1957 to pass, Peggy Duff was the first as expected, a resolution in favour of secretary of the Campaign unilateral abandonment of nuclear weapons for Nuclear Disarmament. -

Winston Churchill's "Crazy Broadcast": Party, Nation, and the 1945 Gestapo Speech

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Winston Churchill's "crazy broadcast": party, nation, and the 1945 Gestapo speech AUTHORS Toye, Richard JOURNAL Journal of British Studies DEPOSITED IN ORE 16 May 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/9424 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication The Journal of British Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/JBR Additional services for The Journal of British Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Winston Churchill's “Crazy Broadcast”: Party, Nation, and the 1945 Gestapo Speech Richard Toye The Journal of British Studies / Volume 49 / Issue 03 / July 2010, pp 655 680 DOI: 10.1086/652014, Published online: 21 December 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0021937100016300 How to cite this article: Richard Toye (2010). Winston Churchill's “Crazy Broadcast”: Party, Nation, and the 1945 Gestapo Speech. The Journal of British Studies, 49, pp 655680 doi:10.1086/652014 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/JBR, IP address: 144.173.176.175 on 16 May 2013 Winston Churchill’s “Crazy Broadcast”: Party, Nation, and the 1945 Gestapo Speech Richard Toye “One Empire; One Leader; One Folk!” Is the Tory campaign master-stroke. As a National jest, It is one of the best, But it’s not an original joke. -

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 a Thesis Submitted to the University of Manches

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 David W. Mottram School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of contents Abstract p.4 Declaration p.5 Copyright statement p.5 Acknowledgements p.6 Introduction p.7 Terminology, sources and methods p.10 Structure of the thesis p.14 Chapter One The Lost War p.16 1.1 The place of ‘Spain’ in British politics p.17 1.2 Viewing ‘Spain’ through external perspectives p.21 1.3 The dispersal, 1939 p.26 Conclusion p.31 Chapter Two Adjustments to the Lost War p.33 2.1 The Communist Party and the International Brigaders: debt of honour p.34 2.2 Labour’s response: ‘The Spanish agitation had become history’ p.43 2.3 Decline in public and political discourse p.48 2.4 The political parties: three Spanish threads p.53 2.5 The personal price of the lost war p.59 Conclusion p.67 2 Chapter Three The lessons of ‘Spain’: Tom Wintringham, guerrilla fighting, and the British war effort p.69 3.1 Wintringham’s opportunity, 1937-1940 p.71 3.2 ‘The British Left’s best-known military expert’ p.75 3.3 Platform for influence p.79 3.4 Defending Britain, 1940-41 p.82 3.5 India, 1942 p.94 3.6 European liberation, 1941-1944 p.98 Conclusion p.104 Chapter Four The political and humanitarian response of Clement Attlee p.105 4.1 Attlee and policy on Spain p.107 4.2 Attlee and the Spanish Republican diaspora p.113 4.3 The signal was Greece p.119 Conclusion p.125 Conclusion p.127 Bibliography p.133 49,910 words 3 Abstract Complexities and divisions over British left-wing responses to the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939 have been well-documented and much studied. -

Sir Richard Acland Et Le Parti Common Wealth Au Cours De La Deuxième Guerre Mondiale

Cercles 11 (2004) LE DERNIER AVATAR DE LA NOTION DE COMMONWEALTH ? Sir Richard Acland et le parti Common Wealth au cours de la deuxième Guerre mondiale ANTOINE CAPET Université de Rouen Avant tout, il convient peut-être de présenter Sir Richard Acland (1906-1990).1 Issu d’une vieille famille de propriétaires terriens du Devon, son grand-père avait été ministre sous Gladstone, et il fut élu député libéral du North Devon en 1935. À la mort de son père quelques mois plus tard, il hérita du domaine foncier familial et du titre de baronet — d’où le Sir de Sir Richard Acland — mais, conformément à ses idéaux égalitaires, il légua toutes ses terres au National Trust en 1943. La virulence de ses prises de position anti-fascistes et anti-apaisement le conduira dans les années 1938-1939 à être en rupture de ban avec son parti, et le tournant de Dunkerque en mai-juin 1940 lui donnera la chance qu’il attendait de « régénérer » la Grande- Bretagne. Le rapprochement qu’il effectue alors avec certains intellectuels de la gauche non travailliste et non communiste aboutira à la création en 1941 du mouvement Forward March, qui fusionnera en 1942 avec le 1941 Committee pour former le parti Common Wealth.2 Avant de parler du parti lui-même, il convient peut-être de faire un petit peu, non pas de philosophie, mais de philologie, et avant d’aborder l’histoire des idées, il convient peut-être de faire un petit peu d’histoire de la langue. Le nom retenu pour le nouveau parti n’est en effet pas anodin. -

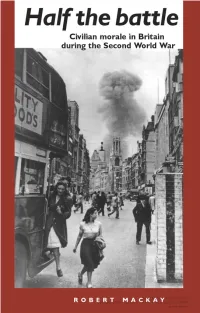

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. -

J\S-Aacj\ Cwton "Wallop., $ Bl Sari Of1{Ports Matd/I

:>- S' Ui-cfAarria, .tffzatirU&r- J\s-aacj\ cwton "Wallop., $ bL Sari of1 {Ports matd/i y^CiJixtkcr- ph JC. THE WALLOP FAMILY y4nd Their Ancestry By VERNON JAMES WATNEY nATF MICROFILMED iTEld #_fe - PROJECT and G. S ROLL * CALL # Kjyb&iDey- , ' VOL. 1 WALLOP — COLE 1/7 OXFORD PRINTED BY JOHN JOHNSON Printer to the University 1928 GENEALOGirA! DEPARTMENT CHURCH ••.;••• P-. .go CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Omnes, si ad originem primam revocantur, a dis sunt. SENECA, Epist. xliv. One hundred copies of this work have been printed. PREFACE '•"^AN these bones live ? . and the breath came into them, and they ^-^ lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.' The question, that was asked in Ezekiel's vision, seems to have been answered satisfactorily ; but it is no easy matter to breathe life into the dry bones of more than a thousand pedigrees : for not many of us are interested in the genealogies of others ; though indeed to those few such an interest is a living thing. Several of the following pedigrees are to be found among the most ancient of authenticated genealogical records : almost all of them have been derived from accepted and standard works ; and the most modern authorities have been consulted ; while many pedigrees, that seemed to be doubtful, have been omitted. Their special interest is to be found in the fact that (with the exception of some of those whose names are recorded in the Wallop pedigree, including Sir John Wallop, K.G., who ' walloped' the French in 1515) every person, whose lineage is shown, is a direct (not a collateral) ancestor of a family, whose continuous descent can be traced since the thirteenth century, and whose name is identical with that part of England in which its members have held land for more than seven hundred and fifty years. -

And Fringe Parties

The University of Manchester Research 'Third' and fringe parties Document Version Accepted author manuscript Link to publication record in Manchester Research Explorer Citation for published version (APA): Morgan, K. (2018). 'Third' and fringe parties. In D. Brown, G. Pentland, & R. Crowcroft (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Modern British Political History, 1800-2000 (Oxford Handbooks). Oxford University Press. Published in: The Oxford Handbook of Modern British Political History, 1800-2000 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on Manchester Research Explorer is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Proof version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Explorer are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Takedown policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please refer to the University of Manchester’s Takedown Procedures [http://man.ac.uk/04Y6Bo] or contact [email protected] providing relevant details, so we can investigate your claim. Download date:27. Sep. 2021 ‘Third’ and fringe parties Kevin Morgan As for the first time in the 1950s millions gathered round their television sets on election night, a new device was unveiled to picture for them the way that things were going. This was the famous swingometer, affably manipulated by Canadian pundit Bob McKenzie, and it represented the contest of Britain’s two great tribes of Labour and Conservatives as a simple oscillating movement between one election and another. -

The Brazen Nose 2014-2015

The Brazen Nose 2014-2015 BRA-19900 The Brazen Nose 2015.indd 1 19/01/2016 14:16 The Brazen Nose The Brazen The Brazen Nose Volume 49 2014-2015 Volume 49, Volume 2014-2015 BRA-19900 Cover.indd 1 20/01/2016 11:30 Printed by: The Holywell Press Limited, www.holywellpress.com BRA-19900 The Brazen Nose 2015.indd 2 19/01/2016 14:16 CONTENTS Records The Amazing Women Portraits A Message from the Editor ............. 5 Project by Margherita De Fraja ....... 97 Senior Members ............................. 9 Alumni Nominations for the Class Lists ..................................... 18 Amazing Brasenose Women Project Graduate Degrees ........................ 21 by Drusilla Gabbott ...................... 100 Matriculations ............................... 26 Memories of Brasenose College Prizes .............................. 30 by Abigail Green .......................... 103 Elections to Scholarships and John Freeman: Face to Face with an Exhibitions 2014 ......................... 33 Enigma by Hugh Purcell ............... 107 College Blues ............................... 38 My Brasenose College Reunion Reports by Toby Young ............................. 123 JCR Report ................................. 40 Patrick Modiano and Kamel Daoud HCR Report ............................... 44 As Principled Investigators Library And Archives Report ........ 46 by Carole Bourne-Taylor ............... 124 Presentations to the Library........... 52 Review of Christopher Penn’s Chapel Report.............................. 54 The Nicholas Brothers & ATW Penn Music -

Opening Minds Howard Gardner

Demos has received support from a wide range of organisations including: Northern Foods, Pearson, Scottish and Newcastle, British Gas, Shell, Stoy Hayward, the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Rowntree Reform Trust, the Inland Revenue Staff Federation, Etam, Heidrich and Struggles, the Charities Aid Foundation, the Corporation of London, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Cable and Wireless Plc. Demos’ Advisory Council includes: John Ashworth Director of the London School of Economics Clive Brooke General Secretary, Inland Revenue Staff Federation Janet Cohen Director, Charterhouse Bank Jack Dromey National Officer TGWU Sir Douglas Hague of Templeton College Jan Hall Chair, Coley Porter Bell Stuart Hall Professor of Sociology, Open University Chris Ham Professor of Health Policy, Birmingham University Charles Handy Visiting Professor, London Business School Ian Hargreaves Deputy Editor, Financial Times Christopher Haskins Chairman of Northern Foods PLC Gerald Holtham Senior International Economist, Lehman Brothers Richard Layard Professor of Economics, LSE David Marquand Professor of Politics, Sheffield University Sheila McKehnie Director, Shelter Julia Middleton Director, Common Purpose Yve Newhold Company Secretary, Hanson plc, Director, British Telecom Sue Richards Director, The Office of Public Management Anita Roddick Group Managing Director, Body Shop PLC Dennis Stevenson Chairman, SRU and the Tate Gallery Martin Taylor Chairman and Chief Executive, Courtaulds Textiles Bob Tyrrell Managing Director, The Henley Centre Other Demos publications available for £5.95 post free from Demos, 9 Bridewell Place, London EC4V6AP. Open access. Some rights reserved. As the publisher of this work, Demos has an open access policy which enables anyone to access our content electronically without charge. We want to encourage the circulation of our work as widely as possible without affecting the ownership of the copyright, which remains with the copyright holder.