A Medical Officer in the Mutiny. Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Lies: Human Property and Domestic Slavery Aboard the Slave Ship Creole

Atlantic Studies ISSN: 1478-8810 (Print) 1740-4649 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjas20 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson To cite this article: Walter Johnson (2008) White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole , Atlantic Studies, 5:2, 237-263, DOI: 10.1080/14788810802149733 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810802149733 Published online: 26 Sep 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 679 View related articles Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjas20 Download by: [Harvard Library] Date: 04 June 2017, At: 20:53 Atlantic Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, August 2008, 237Á263 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson* We cannot suppress the slave trade Á it is a natural operation, as old and constant as the ocean. George Fitzhugh It is one thing to manage a company of slaves on a Virginia plantation and quite another to quell an insurrection on the lonely billows of the Atlantic, where every breeze speaks of courage and liberty. Frederick Douglass This paper explores the voyage of the slave ship Creole, which left Virginia in 1841 with a cargo of 135 persons bound for New Orleans. Although the importation of slaves from Africa into the United States was banned from 1808, the expansion of slavery into the American Southwest took the form of forced migration within the United States, or at least beneath the United States’s flag. -

Mutiny on the Bounty: a Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia

4 Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny on the Bounty: A Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia Introduction Various Bounty narratives emerged as early as 1790. Today, prominent among them are one 20th-century novel and three Hollywood movies. The novel,Mutiny on the Bounty (1932), was written by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, two American writers who had ‘crossed the beach’1 and settled in Tahiti. Mutiny on the Bounty2 is the first volume of their Bounty Trilogy (1936) – which also includes Men against the Sea (1934), the narrative of Bligh’s open-boat voyage, and Pitcairn’s Island (1934), the tale of the mutineers’ final Pacific settlement. The novel was first serialised in the Saturday Evening Post before going on to sell 25 million copies3 and being translated into 35 languages. It was so successful that it inspired the scripts of three Hollywood hits; Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny strongly contributed to substantiating the enduring 1 Greg Dening, ‘Writing, Rewriting the Beach: An Essay’, in Alun Munslow & Robert A Rosenstone (eds), Experiments in Rethinking History, New York & London, Routledge, 2004, p 54. 2 Henceforth referred to in this chapter as Mutiny. 3 The number of copies sold during the Depression suggests something about the appeal of the story. My thanks to Nancy St Clair for allowing me to publish this personal observation. 125 THE BOUNTY FROM THE BEACH myth that Bligh was a tyrant and Christian a romantic soul – a myth that the movies either corroborated (1935), qualified -

Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22

T HE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A TLANTIC SLAVERY AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD I BRAHIMA THIAW AND DEBORAH L. MACK, GUEST EDITORS A tlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Experiences, Representations, and Legacies An Introduction to Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy V The Slavery Business and the Making of “Race” in Britain OLUME 61 and the Caribbean Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME SUPPLEMENT 61 22 From Country Marks to DNA Markers: The Genomic Turn S UPPLEMENT 22 in the Reconstruction of African Identities Diasporic Citizenship under Debate: Law, Body, and Soul Slavery, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Racialization of Africans Sovereignty after Slavery: Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti O CTOBER 2020 From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The “Changing Same” of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants Serving Status on the Gambia River Before and After Abolition The Problem: Religion within the World of Slaves The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons A “tone of voice peculiar to New-England”: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy Raising -

Chapter 10 RIPOSTE and REPRISE

Chapter 10 RIPOSTE AND REPRISE ...I have given the name of the Strait of the Mother of God, to what was formerly known as the Strait of Magellan...because she is Patron and Advocate of these regions....Fromitwill result high honour and glory to the Kings of Spain ... and to the Spanish nation, who will execute the work, there will be no less honour, profit, and increase. ...they died like dogges in their houses, and in their clothes, wherein we found them still at our comming, untill that in the ende the towne being wonderfully taynted with the smell and the savour of the dead people, the rest which remayned alive were driven ... to forsake the towne.... In this place we watered and woodded well and quietly. Our Generall named this towne Port famine.... The Spanish riposte: Sarmiento1 Francisco de Toledo lamented briefly that ‘the sea is so wide, and [Drake] made off with such speed, that we could not catch him’; but he was ‘not a man to dally in contemplations’,2 and within ten days of the hang-dog return of the futile pursuers of the corsair he was planning to lock the door by which that low fellow had entered. Those whom he had sent off on that fiasco seem to have been equally, and reasonably, terrified of catching Drake and of returning to report failure; and we can be sure that the always vehement Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa let his views on their conduct be known. He already had the Viceroy’s ear, having done him signal if not too scrupulous service in the taking of the unfortunate Tupac Amaru (above, Ch. -

From Murmuring to Mutiny Bruce Buchan School of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences Griffith University

Civility at Sea: From Murmuring to Mutiny Bruce Buchan School of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences Griffith University n 1749 the articles of war that regulated life aboard His Britannic Majesty’s I vessels stipulated: If any Person in or belonging to the Fleet shall make or endeavor to make any mutinous Assembly upon any Pretense whatsoever, every Person offending herein, and being convicted thereof by the Sentence of the Court Martial, shall suffer Death: and if any Person in or belong- ing to the Fleet shall utter any Words of Sedition or Mutiny, he shall suffer Death, or such other Punishment as a Court Martial shall deem him to deserve. [Moreover] if any Person in or belonging to the Fleet shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous Words spoken by any, to the Prejudice of His Majesty or Government, or any Words, Practice or Design tending to the Hindrance of the Service, and shall not forthwith reveal the same to the Commanding Officer; or being present at any Mutiny or Sedition, shall not use his utmost Endeavors to suppress the same, he shall be punished as a Court Martial shall think he deserves.1 These stern edicts inform a common image of the cowed life of ordinary sailors aboard vessels of the Royal Navy during its golden age, an image affirmed by the testimony of Jack Nastyface (also known as William Robinson, 1787–ca. 1836), for whom the sailor’s lot involved enforced silence under threat of barbarous and tyrannical punishment.2 In the soundscape of maritime life 1 Articles 19 and 20 of An Act for Amending, Explaining and Reducing into One Act of Parliament, the Laws Relating to the Government of His Majesty’s Ships, Vessels and Forces by Sea (also known as the 1749 Naval Act or the Articles of War), 22 Geo. -

Discovering Lundy

Discovering Lundy The Bulletin of the Lundy Field Society No. 42, December 2012 LFS members on the archaeology walk during the May 2012 ‘Discover Lundy’ week – reports and photos inside Contents View from the top … Keith Hiscock 1 A word from the editors Kevin Williams & Belinda Cox 2 Discover Lundy – an irresistibly good week various contributors 3 A choppy start Alan Rowland 3 Flora walk fernatics Alan Rowland 6 Identifying freshwater invertebrates Alan Rowland 8 Fungus forays John Hedger 10 Discover Lundy – the week in pictures 15 Slow-worm – a new species for Lundy Alan Rowland 18 A July day-trip Andrew Cleave 19 Colyear Dawkins – an inspiration to many Trudy Watt & Keith Kirby 20 A Christmas card drawn by John Dyke David Tyler 21 In memory of Chris Eker André Coutanche 22 Paul [James] wins the Peter Brough Award 23 All at sea Alan Rowland 23 A belated farewell to Nicola Saunders 24 Join in the Devon Birds excursion to Lundy 25 Farewell to the South Light foghorn 25 Raising lots at auction Alan Rowland 25 Getting to know your Puffinus puffinus Madeleine Redway 26 It’s a funny place to meet people, Lundy… David Cann 28 A new species of sea snail 29 A tribute to John Fursdon Tim Davis 30 Skittling the rhododendrons Trevor Dobie & Kevin Williams 32 The Purchase of Lundy for the National Trust (1969) Myrtle Ternstrom 35 The seabird merry-go-round – the photography of Alan Richardson Tim Davis 36 A plane trip to Lundy Peter Moseley 39 The Puffin Slope guardhouse Tim Davis 40 Book reviews: Lundy Island: pirates, plunder and shipwreck Alan Rowland 42 Where am I? A Lundy Puzzle Alan Rowland 43 Publications for sale through the Lundy Field Society 44 See inside back cover for publishing details and copy deadline for the 2013 issue of Discovering Lundy. -

Mutiny in the Royal Navy, 1740 to 1820

ASRXXX10.1177/0003122415618991American Sociological ReviewHechter et al. 6189912015 American Sociological Review 1 –25 Grievances and the Genesis © American Sociological Association 2015 DOI: 10.1177/0003122415618991 of Rebellion: Mutiny in the http://asr.sagepub.com Royal Navy, 1740 to 1820 Michael Hechter,a Steven Pfaff,b and Patrick Underwoodb Abstract Rebellious collective action is rare, but it can occur when subordinates are severely discontented and other circumstances are favorable. The possibility of rebellion is a check—sometimes the only check—on authoritarian rule. Although mutinies in which crews seized control of their vessels were rare events, they occurred throughout the Age of Sail. To explain the occurrence of this form of high-risk collective action, this article holds that shipboard grievances were the principal cause of mutiny. However, not all grievances are equal in this respect. We distinguish between structural grievances that flow from incumbency in a subordinate social position and incidental grievances that incumbents have no expectation of suffering. Based on a case- control analysis of incidents of mutiny compared with controls drawn from a unique database of Royal Navy voyages from 1740 to 1820, in addition to a wealth of qualitative evidence, we find that mutiny was most likely to occur when structural grievances were combined with incidental ones. This finding has implications for understanding the causes of rebellion and the attainment of legitimate social order more generally. Keywords social movements, collective action, insurgency, conflict, military authority Since the 1970s, grievances have had a roller grievances that are situational and unlikely to coaster career in studies of insurgency and appear in standard datasets, together with the collective action. -

Leaving the Mm:J.In to Ply About Lundy, for Securing Trade

Rep. Lundy Field Soc. 4 7 IN THE SHADOW OF THE BLACK ENSIGN: LUNDY'S PART IN PIRACY By C.G. HARFIELD Flat 4, 23 Upperton Gardens, Eastboume, BN21 2AA Pirates! The word simultaneously conjures images of fear, violence and brutality with evocations of adventure on the high seas, swashbuckling heroes and quests for buried treasure. Furthermore, the combination of pirates and islands excites romantic fascination (Cordingly 1995, 162-6), perhaps founded upon the popular and sanitised anti-heroes of literature such as Long John Silver and Captain Hook (Mitchell discusses how literature has romanticised piracy, 1976, 7-10). This paper aims to discover, as far as possible, the part Lundy had to play in piracy in British waters, and to place that in perspective. The nature of the sources for piracy around Lundy will be discussed elsewhere (Harfield, forthcoming); here the story those sources tell is presented. It is not a story of deep-water pirates who traversed the oceans in search of bullion ships, but rather an illustration of the nature of coastal piracy with the bulk of the evidence coming from the Tudor and Stuart periods. LUNDY AS A LANDMARK IN THE EVIDENCE The majority of references to Lundy and pirates mention the island only as a landmark (Harfield, forthcoming). Royal Navy ships are regularly recorded plying the waters between the Scilly Isles, Lundy and the southern coasts of Wales and Ireland (see fig. I) with the intention of clearing these waters of pirates, both British and foreign. For instance, Captain John Donner encountered English pirates ':fifteen miles distant from Lundy Isle" in April 155 7 (7.3.1568, CSP(D)). -

Untitled [Bradley Cesario on Shanghaiing Sailors: A

Mark Strecker. Shanghaiing Sailors: A Maritime History of Forced Labor, 1849/1915. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2014. 260 pp. $39.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-7864-9451-4. Reviewed by Bradley Cesario Published on H-War (August, 2017) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air University) “Shanghaiing” conjures up tales of the sea--of the legal history of the court cases that ended the forced voyages, secret liaisons, and oceanic cross‐ practice in the United States in 1915. ings. While fully understanding and drawing Unfortunately, it must be said that there are upon the romantic side of these tales, Mark two major issues with Strecker’s work. The frst is Strecker sets out to undertake a more scholarly a question of definition. The author notes early in examination of the phenomenon. His work the frst chapter that shanghaiing specifically Shanghaiing Sailors: A Maritime History of refers to “the kidnapping and forcing of a man to Forced Labor, 1849-1915 “presents not only a com‐ serve on board a merchant ship” (p. 3). However, prehensive history of shanghaiing, which peaked many of the examples and anecdotes used relate roughly between 1850 and 1915 … but also exam‐ to entirely separate maritime activities--impress‐ ines the nineteenth-century seafarer’s world and ment/the press gang, privateering, and piracy. All the circumstances that created the perfect storm three of these are covered as activities distinct of events which made shanghaiing a lucrative from shanghaiing, with the result that the reason business” (p. 1). for their inclusion in the volume is somewhat un‐ To accomplish this, Strecker divides his work clear. -

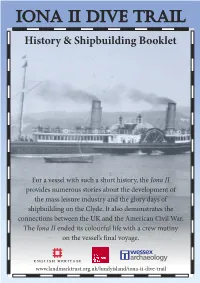

04 Dive Trail History.Cdr

Iona II Dive trail History & Shipbuilding Booklet For a vessel with such a short history, the Iona II provides numerous stories about the development of the mass leisure industry and the glory days of shipbuilding on the Clyde. It also demonstrates the connections between the UK and the American Civil War. The Iona II ended its colourful life with a crew mutiny on the vessel’s final voyage. www.landmarktrust.org.uk/lundyisland/iona-ii-dive-trail navigating the wreck Parts of this Information Booklet correspond with the Shipbuilding Underwater Guide. The letters on the plan below are also on the Shipbuilding Underwater Guide and correspond to areas of interest around the wreck which are explored further in this booklet. The Iona II wreck site is on the east coast of Lundy Island. The seabed around the Iona II wreck is generally flat, with a slight slope east of the amidships area. The seabed is coarse, firm, level mud and fine silt with some areas of fine sand within the wreck and some gravel patches around the boilers. The wreck lies at 22 to 28 metres depending upon the state of the tide. Visibility can vary from 1 to 15 metres. The best time to dive is at slack water, which is two hours either side of low water. N F G A B E Ro D ber t C 0 10m Access to the Iona II Dive Trail is via the Robert wreck buoy. From the Robert’s rudder, head 35m on a bearing of 245 degrees or WSW to reach the Iona II. -

Framing the Mutiny in a Punch Cartoon and a Lucknow Diary

Women and the Indian Mutiny: Framing the Mutiny in a Punch Cartoon and a Lucknow Diary Anna Matei Abstract Artefacts and news coverage created in Britain during the Indian mutiny represented and interpreted that conflict, creating meaning for the public and the victims of the mutiny. Tenniel’s Punch cartoon ‘The British Lion’s Vengeance on the Bengal Tiger’ and Katherine Bartrum’s Lucknow diary constructed meaning through dialogue with national and sectional culture. Both wanted to be understood, and so used and linked elements of British and narrower community tradition to create their representations. In the process, they constructed women’s place in the mutiny too, but while one focused on women as symbolic victims, the other represented their real, personal suffering. The Indian mutiny, 1857-58, was interpreted and defined in contemporary Britain through public discourse built to a large extent by men around the symbol of woman as victim, but also shaped by women as active creators of news and interpretation.1 Literature on the subject of women in the mutiny tends to focus on their function in the national debate as rallying points – defenceless victims whose deaths served the British as cause and justification for violent retribution. The importance of this function, and women’s self-characterisation, to British empire-building in the later nineteenth century is also highlighted.2 This article shall focus on the way the collective conversation around the mutiny led to the framing of women’s experience in India in a way that was, in fact, more complex than the literature suggests. -

The Price of Amity: of Wrecking, Piracy, and the Tragic Loss of the 1750 Spanish Treasure Fleet

The Price of Amity: Of Wrecking, Piracy, and the Tragic Loss of the 1750 Spanish Treasure Fleet Donald G. Shomette La flotte de trésor espagnole navigant de La Havane vers l'Espagne en août 1750 a été prise dans un ouragan et a échoué sur les bancs extérieures de la Virginie, du Maryland et des Carolinas. En dépit des hostilités alors récentes et prolongées entre l'Espagne et l'Angleterre, 1739-48, les gouvernements coloniaux britanniques ont tenté d'aider les Espagnols à sauver leurs navires et à protéger leurs cargaisons. Ces gouvernements, cependant, se sont trouvés impuissants face aux “naufrageurs” rapaces à terre et les pirates en mer qui ont emporté la plus grande partie du trésor et de la cargaison de grande valeur. The Spanish treasure fleet of 1750 sailed from Havana late in August of that year into uncertain waters. The hurricane season was at hand, and there was little reason for confidence in the nominal state of peace with England, whose seamen had for two centuries preyed on the treasure ships. The bloody four-year conflict known in Europe as the War of Austrian Succession and in the Americas as King George's War had been finally concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle only in October 1748 by the wearied principal combatants, France and Spain, which had been aligned against England. England and Spain, in fact, had been at war since 1739. Like many such contests between great empires throughout history, the initial Anglo-Spanish conflict and the larger war of 1744-48 had ended in little more than a draw.