Leaving the Mm:J.In to Ply About Lundy, for Securing Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery

TREASURE ISLAND BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ADAPTED BY BRYONY LAVERY DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. TREASURE ISLAND Copyright © 2016, Bryony Lavery All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of TREASURE ISLAND is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for TREASURE ISLAND are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London, England, W1F 0LE. -

Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: a Proposal for a Reawakening

Indiana Law Journal Volume 82 Issue 1 Article 5 Winter 2007 Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: A Proposal for a Reawakening Robert P. DeWitte Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the International Law Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation DeWitte, Robert P. (2007) "Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: A Proposal for a Reawakening," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 82 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol82/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: A Proposal for a Reawakening ROBERT P. DEWrrE* INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, the United States has repeatedly emphasized the asymmetry between traditional war and the War on TerrorlI-an unorthodox conflict centered on a term which has been continuously reworked and reinvented into its current conception as the "new terrorism." In this rendition of terrorism, fantasy-based ideological agendas are severed from state sponsorship and supplemented with violence calculated to maximize casualties.' The administration of President George W. Bush reinforced and legitimized this characterization with sweeping demonstrations of policy revolution, comprehensive analysis of intelligence community failures,3 and the enactment of broad legislation tailored both to rectify intelligence failures and provide the national security and law enforcement apparatus with the tools necessary to effectively prosecute the "new" war.4 The United States also radically altered its traditional reactive stance on armed conflict by taking preemptive action against Iraq-an enemy it considered a gathering threat 5 due to both state support of terrorism and malignant belligerency. -

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Privateering and Piracy in The

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions Matthew McCarthy The execution of ten pirates at Port Royal, Jamaica in 1823 Charles Ellms, The Pirates Own Book (Gutenberg eBook) http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12216/12216-h/12216-h.htm Please include the following citations when quoting from this dataset: CITATIONS (a) The dataset: Matthew McCarthy, Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy (b) Supporting documentation: Matthew McCarthy, ‘Supporting Documentation’ in Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy 1 Summary Dataset Title: Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions Subject: Prize actions between potential prize vessels and private maritime predators (privateers and pirates) during the Spanish American Revolutions (c.1810- 1830) Data Provider: Matthew McCarthy Maritime Historical Studies Centre (MHSC) University of Hull Email: [email protected] Data Editor: John Nicholls MHSC, University of Hull [email protected] Extent: 1688 records Keywords: Privateering, privateer, piracy, pirate, predation, predator, raiding, raider, prize, commerce, trade, slave trade, shipping, Spanish America, Latin America, Hispanic America, independence, revolution, maritime, history, nineteenth century Citations (a) The dataset: Matthew McCarthy, Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy (b) Supporting documentation: Matthew McCarthy, ‘Supporting Documentation’ in Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy 2 Historical Context Private maritime predation was integral to the Spanish American Revolutions of the early nineteenth century. -

Lots of Paper with Just a Little Wood and Steel an Assembly of Americana Fall of 2014

Read’Em Again Books http://www.read-em-again.com Catalog 5: Number 14-1 Autumn, 2014 A Soldier’s Collection of Native American Cabinet Card Photographs and his Springfield Model 1884 “Trapdoor” Service Rifle Lots of Paper with Just a Little Wood and Steel An Assembly of Americana Fall of 2014 Read’Em Again Books Kurt and Gail Sanftleben 703-580-7252 [email protected] Read’Em Again Books – Kurt & Gail Sanftleben Additional images (and larger too) can be seen by clicking on the Item # or image in each listing. Lots of Paper with a Little Wood and Steel: An Assembly of Americana Read’Em Again Books – Catalog 5: Number 14-1 – Fall of 2014 Terms of Sale If you have any questions about anything you see in this catalog, please contact me at [email protected]. Prices quoted in the catalog are in U.S dollars. When applicable, we must charge sales tax for orders coming from or shipped to addresses in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Standard domestic shipping is at no charge. International shipping varies, but is usually around $30.00 for the first item. All shipments are insured. Reciprocal trade discounts are extended when sales tax numbers are provided. Known customers and institutions may be invoiced; all others are asked to prepay. If you are viewing this catalog on-line, the easiest way for you to complete a purchase is to click the Item # link associated with each listing. This will open a link at our webstore where you will be able to add the item to a shopping cart and then complete your purchase through PayPal by credit card or bank transfer. -

Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22

T HE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A TLANTIC SLAVERY AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD I BRAHIMA THIAW AND DEBORAH L. MACK, GUEST EDITORS A tlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Experiences, Representations, and Legacies An Introduction to Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy V The Slavery Business and the Making of “Race” in Britain OLUME 61 and the Caribbean Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME SUPPLEMENT 61 22 From Country Marks to DNA Markers: The Genomic Turn S UPPLEMENT 22 in the Reconstruction of African Identities Diasporic Citizenship under Debate: Law, Body, and Soul Slavery, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Racialization of Africans Sovereignty after Slavery: Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti O CTOBER 2020 From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The “Changing Same” of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants Serving Status on the Gambia River Before and After Abolition The Problem: Religion within the World of Slaves The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons A “tone of voice peculiar to New-England”: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy Raising -

Adobe PDF File

BOOK REVIEWS David M. Williams and Andrew P. White as well as those from the humanities. The (comp.). A Select Bibliography of British and section on Maritime Law lists work on Irish University Theses About Maritime pollution and the maritime environment, and History, 1792-1990. St. John's, Newfound• on the exploitation of sea resources. It is land: International Maritime Economic particularly useful to have the Open Univer• History Association, 1992. 179 pp., geo• sity and the C.NAA. theses listed. graphical and nominal indices. £10 or $20, The subjects are arranged under twenty- paper; ISBN 0-969588-5. five broad headings; there are numerous chronological geographic and subject sub• The establishment of the International and divisions and an author and geographic British Commissions for Maritime History, index to facilitate cross referencing. Though both of which have assisted in the publica• it is mildly irritating to have details some• tion of this bibliography, illustrates the times split between one column and the steadily growing interest in maritime history next, the whole book is generally convenient during the last thirty years. However, the and easy to use. The introduction explains increasing volume of research in this field the reasons for the format of the biblio• and the varied, detailed work of postgradu• graphy, its pattern of classification and the ate theses have often proved difficult to location and availability of theses. This has locate and equally difficult to consult. This recently much improved and an ASLIB bibliography provides access to this "enor• number is helpfully listed for the majority of mously rich resource" (p. -

Discovering Lundy

Discovering Lundy The Bulletin of the Lundy Field Society No. 42, December 2012 LFS members on the archaeology walk during the May 2012 ‘Discover Lundy’ week – reports and photos inside Contents View from the top … Keith Hiscock 1 A word from the editors Kevin Williams & Belinda Cox 2 Discover Lundy – an irresistibly good week various contributors 3 A choppy start Alan Rowland 3 Flora walk fernatics Alan Rowland 6 Identifying freshwater invertebrates Alan Rowland 8 Fungus forays John Hedger 10 Discover Lundy – the week in pictures 15 Slow-worm – a new species for Lundy Alan Rowland 18 A July day-trip Andrew Cleave 19 Colyear Dawkins – an inspiration to many Trudy Watt & Keith Kirby 20 A Christmas card drawn by John Dyke David Tyler 21 In memory of Chris Eker André Coutanche 22 Paul [James] wins the Peter Brough Award 23 All at sea Alan Rowland 23 A belated farewell to Nicola Saunders 24 Join in the Devon Birds excursion to Lundy 25 Farewell to the South Light foghorn 25 Raising lots at auction Alan Rowland 25 Getting to know your Puffinus puffinus Madeleine Redway 26 It’s a funny place to meet people, Lundy… David Cann 28 A new species of sea snail 29 A tribute to John Fursdon Tim Davis 30 Skittling the rhododendrons Trevor Dobie & Kevin Williams 32 The Purchase of Lundy for the National Trust (1969) Myrtle Ternstrom 35 The seabird merry-go-round – the photography of Alan Richardson Tim Davis 36 A plane trip to Lundy Peter Moseley 39 The Puffin Slope guardhouse Tim Davis 40 Book reviews: Lundy Island: pirates, plunder and shipwreck Alan Rowland 42 Where am I? A Lundy Puzzle Alan Rowland 43 Publications for sale through the Lundy Field Society 44 See inside back cover for publishing details and copy deadline for the 2013 issue of Discovering Lundy. -

Long John Silver's

Representative Photo Offering Memorandum Long John Silver’s 3550 Isleta Boulevard SW | Albuquerque, NM 87105 Confidential Disclaimer This Confidential Memorandum has been prepared by Stan Johnson Company (“SJC”) and is being furnished to you solely for the purpose of your review of the commercial property located at 3550 Isleta Boulevard, SW, Albuquerque, NM 87105 (the “Property”). The material contained in this Offering Memorandum shall be used for the purposes of evaluating the Property for acquisition and shall not be used for any purpose or made available to any other person without the express written consent of Stan Johnson Company (“Broker”). Offered Exclusively by By accepting the Confidential Memorandum, you acknowledge and agree that: (1) all of the information contained herein and any other information you will be receiving in connection with this transaction, whether oral, written or in any other form (collectively, the “Materials”), is confidential; (2) you will not reproduce the Confidential Amar Goli Memorandum in whole or in part; (3) if you do not wish to pursue this matter, you will return this Confidential Associate Director Memorandum to SJC as soon as practicable together with all other materials relating to the Property which you [email protected] may have received from SJC; and (4) any proposed actions by you which are inconsistent in any manner with the P: +1 213.417.9378 foregoing agreements will require the prior written consent of SJC. This Confidential Memorandum has been prepared by SJC, based upon certain information pertaining to the Sam Alison Property and any information obtained from SJC to assist interested parties in making their own evaluation of Regional Director - West the Property is offered on a no representation or warranty provision other than customary warranties of title [email protected] and is sold on an “as-is, where-is” basis and with all faults. -

Ye Intruders Beware: Fantastical Pirates in the Golden Age of Illustration

YE INTRUDERS BEWARE: FANTASTICAL PIRATES IN THE GOLDEN AGE OF ILLUSTRATION Anne M. Loechle Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of the History of Art Indiana University November 2010 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _________________________________ Chairperson, Sarah Burns, Ph.D. __________________________________ Janet Kennedy, Ph.D. __________________________________ Patrick McNaughton, Ph.D. __________________________________ Beverly Stoeltje, Ph.D. November 9, 2010 ii ©2010 Anne M. Loechle ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii Acknowledgments I am indebted to many people for the help and encouragement they have given me during the long duration of this project. From academic and financial to editorial and emotional, I was never lacking in support. I am truly thankful, not to mention lucky. Sarah Burns, my advisor and mentor, supported my ideas, cheered my successes, and patiently edited and helped me to revise my failures. I also owe her thanks for encouraging me to pursue an unorthodox topic. From the moment pirates came up during one of our meetings in the spring of 2005, I was hooked. She knew it, and she continuously suggested ways to expand the idea first into an independent study, and then into this dissertation. My dissertation committee – Janet Kennedy, Patrick McNaughton, and Beverly Stoeltje – likewise deserves my thanks for their mentoring and enthusiasm. Other scholars have graciously shared with me their knowledge and input along the way. David M. Lubin read a version of my third chapter and gave me helpful advice, opening up to me new ways of thinking about Howard Pyle in particular. -

Teacher Guide Page Ii

Page i Table of Contents How to Use Lightning Literature & Composition for Grade 8. Page 1 Student Guide Welcome to Lightning Literature . Page 1 Introductions/While You Read . Page 1 Vocabulary Lists. Page 1 Comprehension Questions. Page 2 Literary Lessons. Page 2 Mini-Lessons . Page 3 Writing Exercises . Page 3 Workbook . Page 4 Discussion Questions . Page 5 Why Use Lightning Literature & Composition for Grade 8 . Page 5 The Importance of Reading . Page 5 Reading Poetry . Page 6 The Importance of Writing . .. Page 7 Weekly Planning Schedule . Page 8 Chapter One: “A Crazy Tale” by G. K. Chesterton (Stories & Poems for Extremely Intelligent Children) . Page 15 Answers to Comprehension Questions . Page 17 Literary Lesson: Author’s Purpose. Page 17 Mini-Lesson: Taking Notes . Page 18 Writing Exercises . Page 18 Discussion Questions. Page 19 Workbook Answers. Page 19 Table of Contents—Lightning Lit & Comp 8th Grade—Teacher Guide Page ii Chapter Two: Robert L. Stevenson (Treasure Island) . Page 25 Answers to Comprehension Questions . Page 27 Literary Lesson: Setting. Page 33 Mini-Lesson: Rewriting in Your Own Words. Page 33 Writing Exercises . Page 34 Discussion Questions. Page 34 Workbook Answers. Page 35 Chapter Three: Vivid Imagery in Poetry (Stories & Poems for Extremely Intelligent Children). Page 41 Answers to Comprehension Questions . Page 43 Literary Lesson: Vivid Imagery in Poetry . Page 44 Mini-Lesson: Free Verse and Ballad . Page 45 Writing Exercises . Page 46 Discussion Questions. Page 46 Workbook Answers. Page 47 Chapter Four: Isaac B. Singer (A Day of Pleasure) . Page 53 Answers to Comprehension Questions . Page 55 Literary Lesson: Sharing Your Culture . Page 59 Mini-Lesson: Rewriting Your Own Words . -

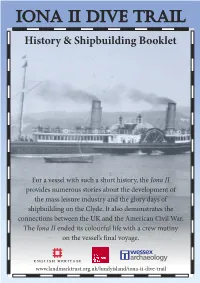

04 Dive Trail History.Cdr

Iona II Dive trail History & Shipbuilding Booklet For a vessel with such a short history, the Iona II provides numerous stories about the development of the mass leisure industry and the glory days of shipbuilding on the Clyde. It also demonstrates the connections between the UK and the American Civil War. The Iona II ended its colourful life with a crew mutiny on the vessel’s final voyage. www.landmarktrust.org.uk/lundyisland/iona-ii-dive-trail navigating the wreck Parts of this Information Booklet correspond with the Shipbuilding Underwater Guide. The letters on the plan below are also on the Shipbuilding Underwater Guide and correspond to areas of interest around the wreck which are explored further in this booklet. The Iona II wreck site is on the east coast of Lundy Island. The seabed around the Iona II wreck is generally flat, with a slight slope east of the amidships area. The seabed is coarse, firm, level mud and fine silt with some areas of fine sand within the wreck and some gravel patches around the boilers. The wreck lies at 22 to 28 metres depending upon the state of the tide. Visibility can vary from 1 to 15 metres. The best time to dive is at slack water, which is two hours either side of low water. N F G A B E Ro D ber t C 0 10m Access to the Iona II Dive Trail is via the Robert wreck buoy. From the Robert’s rudder, head 35m on a bearing of 245 degrees or WSW to reach the Iona II. -

England's Naval Dominance

CK_5_TH_HG_P104_230.QXD 2/14/06 2:23 PM Page 196 V. England from the Golden Age to the Glorious Revolution Although most people expected Elizabeth to marry, she never did. She was Teaching Idea known as the Virgin Queen and liked to say that she was “married to England.” Stage an Elizabethan Day. Have groups The period during which Elizabeth I reigned is sometimes called the of students do research to find out what Elizabethan Age in recognition of the impact that Elizabeth had on her nation. kind of clothes the Elizabethans wore, The term Elizabethan is used as a noun to designate a person who lived during what they ate, what music they listened that time, e.g., “Elizabethans became used to warnings that the Spanish were to, and what they read. Have the groups about to invade.” It is also used as an adjective: “Elizabethan poets were highly plan a class event to showcase this inventive in their use of imagery.” The Elizabethan Age is especially noted for its information. It could be an event in output of excellent literature. Elizabeth was a great patron of the arts. Elizabethan which students wear costumes, pre- playwrights and poets included William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, Christopher pare easy-to-make simulated Marlowe, Sir Phillip Sidney, and Edmund Spenser. Elizabethan dishes, play tapes of Elizabethan music, etc. Or if there is England’s Naval Dominance less time and fewer resources, the “event” could be oral presentations of It was actually Henry VIII who started England on the road to naval suprem- illustrated reports about Elizabethan acy.