Mutiny in the Royal Navy, 1740 to 1820

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation & Research Literature: the State of Knowledge on BJA

Evaluation & Research Literature: The State of Knowledge on BJA-Funded Programs March 27, 2015 Overview The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) is a leader in developing and implementing evidence-based criminal justice policy and practice. BJA’s mission is to provide leadership in services and grant administration and criminal justice policy development to support local, state, and Tribal justice strategies to achieve safer communities. This is accomplished in many criminal justice topic areas, including adjudication, corrections, counter-terrorism, crime prevention, justice information sharing, law enforcement, justice and mental health, substance abuse, and Tribal justice. Under each topic area, BJA funds numerous programs and initiatives at the Tribal, local, and state level. In partnership with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), other Federal partners, and many other research partners, many of these programs have been evaluated, while others have not. The intent of the following report is to assess the state of knowledge as determined by data collection, research, and evaluation of and related to BJA- funded programs. This report is a resource that can be a reference for both evaluation and research literature on many BJA programs. It also identifies programs and practices for which U.S. Department of Justice resources have played a critical role in generating innovative programs and sound practices. This report identifies programs and practices with a solid foundation of evidence, as well as those that may benefit from further research and evaluation. Program evaluation is a systematic, objective process for determining the success of a policy or program. Evaluations assess whether and to what extent the program is achieving its goals and objectives. -

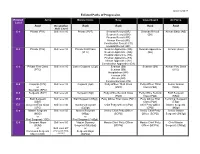

Enlisted Paths of Progression Chart

Updated 2/24/17 Enlisted Paths of Progression Enlisted Army Marine Corps Navy Coast Guard Air Force Level Rank Occupation Rank Rank Rank Rank Skill Level E-1 Private (PV1) Skill level 10 Private (PVT) Seaman Recruit (SR) Seaman Recruit Airman Basic (AB) Seaman Recruit (SR) (SR) Fireman Recruit (FR) Airman Recruit (AR) Construction Recruit (CR) Hospital Recruit (HR) E-2 Private (PV2) Skill level 10 Private First Class Seaman Apprentice (SA) Seaman Apprentice Airman (Amn) (PFC) Seaman Apprentice (SA) (SA) Hospital Apprentice (HA) Fireman Apprentice (FA) Airman Apprentice (AA) Construction Apprentice (CA) E-3 Private First Class Skill level 10 Lance Corporal (LCpl) Seaman (SN) Seaman (SN) Airman First Class (PFC) Seaman (SN) (A1C) Hospitalman (HN) Fireman (FN) Airman (AN) Constructionman (CN) E-4 Corporal (CPL) Skill level 10 Corporal (Cpl) Petty Officer Third Class Petty Officer Third Senior Airman or (PO3) Class (PO3) (SRA) Specialist (SPC) E-5 Sergeant (SGT) Skill level 20 Sergeant (Sgt) Petty Office Second Class Petty Office Second Staff Sergeant (PO2) Class (PO2) (SSgt) E-6 Staff Sergeant Skill level 30 Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Petty Officer First Class (PO1) Petty Officer First Technical Sergeant (SSG) Class (PO1) (TSgt) E-7 Sergeant First Class Skill level 40 Gunnery Sergeant Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Chief Petty Officer Master Sergeant (SFC) (GySgt) (CPO) (MSgt) E-8 Master Sergeant Skill level 50 Master Sergeant Senior Chief Petty Officer Senior Chief Petty Senior Master (MSG) (MSgt) (SCPO) Officer (SCPO) Sergeant (SMSgt) or or First Sergeant (1SG) First Sergeant (1stSgt) E-9 Sergeant Major Skill level 50 Master Gunnery Master Chief Petty Officer Master Chief Petty Chief Master (SGM) Sergeant (MGySgt) (MCPO) Officer (MCPO) Sergeant (CMSgt) or Skill level 60* or Command Sergeant (*For some fields, Sergeant Major Major (CSM) not all.) (SgtMaj) . -

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

2010 Hyundai Genesis

2010 HYUNDAI_GENESIS If you’re reading this brochure, chances are you’re the kind of automotive enthusiast who, instead of simply opening your wallet and adding a status trophy to your garage, prefers to open something else: Your mind. It’s a refreshing attitude that often leads you to discover truly rewarding experiences, from new and unexpected sources. Like Genesis, from Hyundai. Nobody was looking for Hyundai to build a luxury car that would challenge the automotive elite. But we did. Nobody expected us to benchmark the industry’s best, then apply the art and science needed to meet those marks. But we did. Nobody thought we’d charm the pants off a jury of North America’s most esteemed automotive journalists, or be named "The Most Appealing Midsize Premium Car" in 2009 by J.D. Power and Associates.1 But we did. And by doing what few people expected of us, we now find ourselves as a car company that a lot of people are starting to think about in a whole new way. It’s 2010. Welcome to Hyundai. 1 The Hyundai Genesis received the highest numerical score among midsize premium cars in the proprietary J.D. Power and Associates 2009 Automotive Performance Execution and Layout Study.SM Study based on responses from 80,930 new-vehicle owners, measuring 245 models and measures opinions after 90 days of ownership. Proprietary study results are based on experiences and perceptions of owners surveyed in February-May 2009. Your experiences may vary. Visit jdpower.com. geNesIS 3.8 IN TItaNIUM GRay metallIC MEASURE GENESIS AGAINST OTHER LUXURY SEDANS. -

Hair: the Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960S’

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Winchester Research Repository University of Winchester ‘Hair: The Performance of Rebellion in American Musical Theatre of the 1960s’ Sarah Elisabeth Browne ORCID: 0000-0003-2002-9794 Doctor of Philosophy December 2017 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester MPhil/PhD THESES OPEN ACCESS / EMBARGO AGREEMENT FORM This Agreement should be completed, signed and bound with the hard copy of the thesis and also included in the e-copy. (see Thesis Presentation Guidelines for details). Access Permissions and Transfer of Non-Exclusive Rights By giving permission you understand that your thesis will be accessible to a wide variety of people and institutions – including automated agents – via the World Wide Web and that an electronic copy of your thesis may also be included in the British Library Electronic Theses On-line System (EThOS). Once the Work is deposited, a citation to the Work will always remain visible. Removal of the Work can be made after discussion with the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, who shall make best efforts to ensure removal of the Work from any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement. Agreement: I understand that the thesis listed on this form will be deposited in the University of Winchester’s Research Repository, and by giving permission to the University of Winchester to make my thesis publically available I agree that the: • University of Winchester’s Research Repository administrators or any third party with whom the University of Winchester’s Research Repository has an agreement to do so may, without changing content, translate the Work to any medium or format for the purpose of future preservation and accessibility. -

White Lies: Human Property and Domestic Slavery Aboard the Slave Ship Creole

Atlantic Studies ISSN: 1478-8810 (Print) 1740-4649 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjas20 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson To cite this article: Walter Johnson (2008) White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole , Atlantic Studies, 5:2, 237-263, DOI: 10.1080/14788810802149733 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810802149733 Published online: 26 Sep 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 679 View related articles Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjas20 Download by: [Harvard Library] Date: 04 June 2017, At: 20:53 Atlantic Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, August 2008, 237Á263 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson* We cannot suppress the slave trade Á it is a natural operation, as old and constant as the ocean. George Fitzhugh It is one thing to manage a company of slaves on a Virginia plantation and quite another to quell an insurrection on the lonely billows of the Atlantic, where every breeze speaks of courage and liberty. Frederick Douglass This paper explores the voyage of the slave ship Creole, which left Virginia in 1841 with a cargo of 135 persons bound for New Orleans. Although the importation of slaves from Africa into the United States was banned from 1808, the expansion of slavery into the American Southwest took the form of forced migration within the United States, or at least beneath the United States’s flag. -

Bodyslam from the Top Rope: Unequal Bargaining Power and Professional Wrestling's Failure to Unionize Stephen S

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Entertainment & Sports Law Review 1-1-1995 Bodyslam From the Top Rope: Unequal Bargaining Power and Professional Wrestling's Failure to Unionize Stephen S. Zashin Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umeslr Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Stephen S. Zashin, Bodyslam From the Top Rope: Unequal Bargaining Power and Professional Wrestling's Failure to Unionize, 12 U. Miami Ent. & Sports L. Rev. 1 (1995) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umeslr/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Entertainment & Sports Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zashin: Bodyslam From the Top Rope: Unequal Bargaining Power and Professi UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI ENTERTAINMENT & SPORTS LAW REVIEW ARTICLES BODYSLAM FROM THE TOP ROPE: UNEQUAL BARGAINING POWER AND PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING'S FAILURE TO UNIONIZE STEPHEN S. ZASHIN* Wrestlers are a sluggish set, and of dubious health. They sleep out their lives, and whenever they depart ever so little from their regular diet they fall seriously ill. Plato, Republic, III I don't give a damn if it's fake! Kill the son-of-a-bitch! An Unknown Wrestling Fan The lights go black and the crowd roars in anticipation. Light emanates only from the scattered popping flash-bulbs. As the frenzy grows to a crescendo, Also Sprach Zarathustra' pierces the crowd's noise. -

Mutiny on the Bounty: a Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia

4 Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny on the Bounty: A Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia Introduction Various Bounty narratives emerged as early as 1790. Today, prominent among them are one 20th-century novel and three Hollywood movies. The novel,Mutiny on the Bounty (1932), was written by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, two American writers who had ‘crossed the beach’1 and settled in Tahiti. Mutiny on the Bounty2 is the first volume of their Bounty Trilogy (1936) – which also includes Men against the Sea (1934), the narrative of Bligh’s open-boat voyage, and Pitcairn’s Island (1934), the tale of the mutineers’ final Pacific settlement. The novel was first serialised in the Saturday Evening Post before going on to sell 25 million copies3 and being translated into 35 languages. It was so successful that it inspired the scripts of three Hollywood hits; Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny strongly contributed to substantiating the enduring 1 Greg Dening, ‘Writing, Rewriting the Beach: An Essay’, in Alun Munslow & Robert A Rosenstone (eds), Experiments in Rethinking History, New York & London, Routledge, 2004, p 54. 2 Henceforth referred to in this chapter as Mutiny. 3 The number of copies sold during the Depression suggests something about the appeal of the story. My thanks to Nancy St Clair for allowing me to publish this personal observation. 125 THE BOUNTY FROM THE BEACH myth that Bligh was a tyrant and Christian a romantic soul – a myth that the movies either corroborated (1935), qualified -

EPW Matches EPIC/QHD: “The Finisher” Racer Mckay (1,524-216-54) *17 $2,454,800 … #160 Or 501

#32 Mega Empire Champion * wins 10 free EPW matches EPIC/QHD: “The Finisher” Racer McKay (1,524-216-54) *17 $2,454,800 … #160 or 501 Heritage Champion * wins 5 free EPW matches EPIC/QHD: “The Uprising” Dagger Wolfkill (1,222-156-28) *17 $1,857,600 … #158 or 502 Chaotic Champion ORDER: Hazrat (407-100-15) *20 $682,200 … #72 or 503 Primacy Champion EPIC/YmY: Hot Toddy (487-122-28) *7 $974,500 … #128 or 504 No Mercy Champion ORDER: Sicko the Clown (276-81-21) *14 $500,400 … #81 or 505 Noble Champion EDGE: Apostle (5-7-1) *2 $66,400 … #135 or 506 Anarchy Rising Champion EPIC/QHD: “Showtime” Tommy Christopher September 2021 (1,781-313-74) *19 $2,921,100 … #48 or 507 Shining Knight Champion EPIC/3HDR: “King of Riches” Shota Tokido (1,212-207-51) *15 $1,961,600 … #159 or 508 Explicit Champion EPIC/YmY: Whiskey Sour (237-89-14) *4 $558,300 … #75 or 509 Eminence Champion Johnny Moore Fiend (723-166-31) *19 $1,275,200 … #70 or 510 Despair Champion * from the battle royal EPIC/3HDR: “Suicidal Nightmare” Darby Christopher (1,428-273-64) *17 $2,480,600 … #50 or 511 Regal Champion Xander Wolfe (212-85-15) *6 $532,800 … #78 or 512 Total Annihilation Champions VIRUS: “Spotlight” Carlos Spickelmier and “King of Monsters” Wesley Spickelmier #56 & #77 or 789 Crossfire Champions EDGE: Joe Bloggs and John Doe #59 & #61 or 987 Dastardly Deeds Champions * win another 5 free matches LPPF: Slaughterdog Kreo, Slaughterdog Cujo, and Slaughterdog Rex #132, #133, & #134 or 789 Pure Blood Champions EPIC/YmY: Whiskey Sour, EPIC/AoS: Jerrad Syn, and Vicious Valentine #75, #129, & #157 or 987 Battle Royal Winner * wins 19 free EPW matches EPIC/YmY: Hot Toddy (487-122-28) *7 $974,500 … #128 1. -

Abraham!” “Yes?” Answered Abraham

January 17, 2021 - Sacrifice Read this, from Genesis 22: God said, “Abraham!” “Yes?” answered Abraham. “I’m listening.” 2 He said, “Take your dear son Isaac whom you love and go to the land of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains that I’ll point out to you.” 3-5 Abraham got up early in the morning and saddled his donkey. He took two of his young servants and his son Isaac. He had split wood for the burnt offering. He set out for the place God had directed him. On the third day he looked up and saw the place in the distance. Abraham told his two young servants, “Stay here with the donkey. The boy and I are going over there to worship; then we’ll come back to you.” 6 Abraham took the wood for the burnt offering and gave it to Isaac his son to carry. He carried the flint and the knife. The two of them went off together. 7 Isaac said to Abraham his father, “Father?” “Yes, my son.” “We have flint and wood, but where’s the sheep for the burnt offering?” 8 Abraham said, “Son, God will see to it that there’s a sheep for the burnt offering.” And they kept on walking together. 9-10 They arrived at the place to which God had directed him. Abraham built an altar. He laid out the wood. Then he tied up Isaac and laid him on the wood. Abraham reached out and took the knife to kill his son. -

News Briefs the Elite Runners Were Those Who Are Responsible for Vive

VOL. 117 - NO. 16 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, APRIL 19, 2013 $.30 A COPY 1st Annual Daffodil Day on the MARATHON MONDAY MADNESS North End Parks Celebrates Spring by Sal Giarratani Someone once said, “Ide- by Matt Conti ologies separate us but dreams and anguish unite us.” I thought of this quote after hearing and then view- ing the horrific devastation left in the aftermath of the mass violence that occurred after two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon at 2:50 pm. Three people are reported dead and over 100 injured in the may- hem that overtook the joy of this annual event. At this writing, most are assuming it is an act of ter- rorism while officials have yet to call it such at this time 24 hours later. The Ribbon-Cutting at the 1st Annual Daffodil Day. entire City of Boston is on (Photo by Angela Cornacchio) high alert. The National On Sunday, April 14th, the first annual Daffodil Day was Guard has been mobilized celebrated on the Greenway. The event was hosted by The and stationed at area hospi- Friends of the North End Parks (FOTNEP) in conjunction tals. Mass violence like what with the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway Conservancy and North we all just experienced can End Beautification Committee. The celebration included trigger overwhelming feel- ings of anxiety, anger and music by the Boston String Academy and poetry, as well as (Photo by Andrew Martorano) daffodils. Other activities were face painting, a petting zoo fear. Why did anyone or group and a dog show held by RUFF. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. June 29, 2020 to Sun. July 5, 2020 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. June 29, 2020 to Sun. July 5, 2020 Monday June 29, 2020 7:20 PM ET / 4:20 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT AXS TV Insider Rock Legends Featuring highlights and interviews with the biggest names in music. Earth, Wind & Fire - Earth, Wind & Fire is an American band that has spanned the musical genres of R&B, soul, funk, jazz, disco, pop, rock, Latin and African. They are one of the most successful 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT bands of all time. Leading music critics cast fresh light on their career. Rock Legends Journey - Journey is an American rock band that formed in San Francisco in 1973, composed of 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT former members of Santana and Frumious Bandersnatch. The band has gone through several Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar phases; its strongest commercial success occurred between 1978 and 1987. Sunset Strip - Sammy heads to Sunset Blvd to reminisce at the Whisky A-Go-Go before visit- ing with former Mötley Crüe drummer Tommy Lee at his house. After cooking together and Premiere exchanging stories, the guys rock out in Tommy’s studio. 8:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM PT Nothing But Trailers 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Sometimes the best part of the movie is the preview! Watch some of the best trailers, old and The Big Interview new, during this special presentation. Dwight Yoakam - Country music trailblazer takes time from his latest tour to discuss his career and how he made it big in the business far from Nashville.