From Murmuring to Mutiny Bruce Buchan School of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences Griffith University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Lies: Human Property and Domestic Slavery Aboard the Slave Ship Creole

Atlantic Studies ISSN: 1478-8810 (Print) 1740-4649 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjas20 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson To cite this article: Walter Johnson (2008) White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole , Atlantic Studies, 5:2, 237-263, DOI: 10.1080/14788810802149733 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14788810802149733 Published online: 26 Sep 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 679 View related articles Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjas20 Download by: [Harvard Library] Date: 04 June 2017, At: 20:53 Atlantic Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, August 2008, 237Á263 White lies: Human property and domestic slavery aboard the slave ship Creole Walter Johnson* We cannot suppress the slave trade Á it is a natural operation, as old and constant as the ocean. George Fitzhugh It is one thing to manage a company of slaves on a Virginia plantation and quite another to quell an insurrection on the lonely billows of the Atlantic, where every breeze speaks of courage and liberty. Frederick Douglass This paper explores the voyage of the slave ship Creole, which left Virginia in 1841 with a cargo of 135 persons bound for New Orleans. Although the importation of slaves from Africa into the United States was banned from 1808, the expansion of slavery into the American Southwest took the form of forced migration within the United States, or at least beneath the United States’s flag. -

Mutiny on the Bounty: a Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia

4 Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny on the Bounty: A Piece of Colonial Historical Fiction Sylvie Largeaud-Ortega University of French Polynesia Introduction Various Bounty narratives emerged as early as 1790. Today, prominent among them are one 20th-century novel and three Hollywood movies. The novel,Mutiny on the Bounty (1932), was written by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall, two American writers who had ‘crossed the beach’1 and settled in Tahiti. Mutiny on the Bounty2 is the first volume of their Bounty Trilogy (1936) – which also includes Men against the Sea (1934), the narrative of Bligh’s open-boat voyage, and Pitcairn’s Island (1934), the tale of the mutineers’ final Pacific settlement. The novel was first serialised in the Saturday Evening Post before going on to sell 25 million copies3 and being translated into 35 languages. It was so successful that it inspired the scripts of three Hollywood hits; Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny strongly contributed to substantiating the enduring 1 Greg Dening, ‘Writing, Rewriting the Beach: An Essay’, in Alun Munslow & Robert A Rosenstone (eds), Experiments in Rethinking History, New York & London, Routledge, 2004, p 54. 2 Henceforth referred to in this chapter as Mutiny. 3 The number of copies sold during the Depression suggests something about the appeal of the story. My thanks to Nancy St Clair for allowing me to publish this personal observation. 125 THE BOUNTY FROM THE BEACH myth that Bligh was a tyrant and Christian a romantic soul – a myth that the movies either corroborated (1935), qualified -

Chapter 10 RIPOSTE and REPRISE

Chapter 10 RIPOSTE AND REPRISE ...I have given the name of the Strait of the Mother of God, to what was formerly known as the Strait of Magellan...because she is Patron and Advocate of these regions....Fromitwill result high honour and glory to the Kings of Spain ... and to the Spanish nation, who will execute the work, there will be no less honour, profit, and increase. ...they died like dogges in their houses, and in their clothes, wherein we found them still at our comming, untill that in the ende the towne being wonderfully taynted with the smell and the savour of the dead people, the rest which remayned alive were driven ... to forsake the towne.... In this place we watered and woodded well and quietly. Our Generall named this towne Port famine.... The Spanish riposte: Sarmiento1 Francisco de Toledo lamented briefly that ‘the sea is so wide, and [Drake] made off with such speed, that we could not catch him’; but he was ‘not a man to dally in contemplations’,2 and within ten days of the hang-dog return of the futile pursuers of the corsair he was planning to lock the door by which that low fellow had entered. Those whom he had sent off on that fiasco seem to have been equally, and reasonably, terrified of catching Drake and of returning to report failure; and we can be sure that the always vehement Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa let his views on their conduct be known. He already had the Viceroy’s ear, having done him signal if not too scrupulous service in the taking of the unfortunate Tupac Amaru (above, Ch. -

PIRATES Ssfix.Qxd

E IFF RE D N 52 T DISCOVERDISCOVER FAMOUS PIRATES B P LAC P A KBEARD A IIRRAATT Edward Teach, E E ♠ E F R better known as Top Quality PlayingPlaying CardsCards IF E ♠ SS N Plastic Coated D Blackbeard, was T one of the most feared and famous 52 pirates that operated Superior Print along the Caribbean and A Quality PIR Atlantic coasts from ATE TR 1717-18. Blackbeard ♦ EAS was most infamous for U RE his frightening appear- ance. He was huge man with wild bloodshot eyes, and a mass of tangled A hair and beard that was twisted into dreadlocks, black ribbons. In battle, he made himself andeven thenmore boundfearsome with by ♦ wearing smoldering cannon fuses stuffed under his hat, creating black smoke wafting about his head. During raids, Blackbeard car- ried his cutlass between his teeth as he scaled the side of a The lure of treasure was the driving force behind all the ship. He was hunted down by a British Navy crew risks taken by Pirates. It was ♠ at Ocracoke Inlet in 1718. possible to acquire more booty Blackbeard fought a furious battle, and was slain ♠ in a single raid than a man or jewelry. It was small, light, only after receiving over 20 cutlass wounds, and could earn in a lifetime of regu- and easy to carry and was A five pistol shots. lar work. In 1693, Thomas widely accepted as currency. A Tew once plundered a ship in Other spoils were more WALKING THE PLANK the Indian Ocean where each practical: tobacco, weapons, food, alco- member received 3000 hol, and the all important doc- K K ♦ English pounds, equal to tor’s medical chest. -

Mutiny in the Royal Navy, 1740 to 1820

ASRXXX10.1177/0003122415618991American Sociological ReviewHechter et al. 6189912015 American Sociological Review 1 –25 Grievances and the Genesis © American Sociological Association 2015 DOI: 10.1177/0003122415618991 of Rebellion: Mutiny in the http://asr.sagepub.com Royal Navy, 1740 to 1820 Michael Hechter,a Steven Pfaff,b and Patrick Underwoodb Abstract Rebellious collective action is rare, but it can occur when subordinates are severely discontented and other circumstances are favorable. The possibility of rebellion is a check—sometimes the only check—on authoritarian rule. Although mutinies in which crews seized control of their vessels were rare events, they occurred throughout the Age of Sail. To explain the occurrence of this form of high-risk collective action, this article holds that shipboard grievances were the principal cause of mutiny. However, not all grievances are equal in this respect. We distinguish between structural grievances that flow from incumbency in a subordinate social position and incidental grievances that incumbents have no expectation of suffering. Based on a case- control analysis of incidents of mutiny compared with controls drawn from a unique database of Royal Navy voyages from 1740 to 1820, in addition to a wealth of qualitative evidence, we find that mutiny was most likely to occur when structural grievances were combined with incidental ones. This finding has implications for understanding the causes of rebellion and the attainment of legitimate social order more generally. Keywords social movements, collective action, insurgency, conflict, military authority Since the 1970s, grievances have had a roller grievances that are situational and unlikely to coaster career in studies of insurgency and appear in standard datasets, together with the collective action. -

Untitled [Bradley Cesario on Shanghaiing Sailors: A

Mark Strecker. Shanghaiing Sailors: A Maritime History of Forced Labor, 1849/1915. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2014. 260 pp. $39.95, paper, ISBN 978-0-7864-9451-4. Reviewed by Bradley Cesario Published on H-War (August, 2017) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air University) “Shanghaiing” conjures up tales of the sea--of the legal history of the court cases that ended the forced voyages, secret liaisons, and oceanic cross‐ practice in the United States in 1915. ings. While fully understanding and drawing Unfortunately, it must be said that there are upon the romantic side of these tales, Mark two major issues with Strecker’s work. The frst is Strecker sets out to undertake a more scholarly a question of definition. The author notes early in examination of the phenomenon. His work the frst chapter that shanghaiing specifically Shanghaiing Sailors: A Maritime History of refers to “the kidnapping and forcing of a man to Forced Labor, 1849-1915 “presents not only a com‐ serve on board a merchant ship” (p. 3). However, prehensive history of shanghaiing, which peaked many of the examples and anecdotes used relate roughly between 1850 and 1915 … but also exam‐ to entirely separate maritime activities--impress‐ ines the nineteenth-century seafarer’s world and ment/the press gang, privateering, and piracy. All the circumstances that created the perfect storm three of these are covered as activities distinct of events which made shanghaiing a lucrative from shanghaiing, with the result that the reason business” (p. 1). for their inclusion in the volume is somewhat un‐ To accomplish this, Strecker divides his work clear. -

04 Dive Trail History.Cdr

Iona II Dive trail History & Shipbuilding Booklet For a vessel with such a short history, the Iona II provides numerous stories about the development of the mass leisure industry and the glory days of shipbuilding on the Clyde. It also demonstrates the connections between the UK and the American Civil War. The Iona II ended its colourful life with a crew mutiny on the vessel’s final voyage. www.landmarktrust.org.uk/lundyisland/iona-ii-dive-trail navigating the wreck Parts of this Information Booklet correspond with the Shipbuilding Underwater Guide. The letters on the plan below are also on the Shipbuilding Underwater Guide and correspond to areas of interest around the wreck which are explored further in this booklet. The Iona II wreck site is on the east coast of Lundy Island. The seabed around the Iona II wreck is generally flat, with a slight slope east of the amidships area. The seabed is coarse, firm, level mud and fine silt with some areas of fine sand within the wreck and some gravel patches around the boilers. The wreck lies at 22 to 28 metres depending upon the state of the tide. Visibility can vary from 1 to 15 metres. The best time to dive is at slack water, which is two hours either side of low water. N F G A B E Ro D ber t C 0 10m Access to the Iona II Dive Trail is via the Robert wreck buoy. From the Robert’s rudder, head 35m on a bearing of 245 degrees or WSW to reach the Iona II. -

Wildwill's Collector's Guide to Wizkids' Pirates of the Spanish Main

WildWill’s Collector’s Guide to WizKids’ By Captain William “WildWill” Noetling Includes Price Guides, Collector’s Checklists, Bonus Game Scenario and MORE! WildWill’s Collector’s Guide to WizKids’ Pirates of the Spanish Main. Copyright ©2006 by William Noetling. This guide was created for educational and entertainment purposes only. All prices lists are printed as a guide only, and not an offer to buy or sell game pieces. This guide is not sponsored, endorsed, or otherwise affiliated with any of the companies or products featured within this guide. This is not an Official Publication. This guide and its editorial content remain the property of the writer and publisher. Written permission must be obtained from the author to publish, circulate, or otherwise disseminate this guide in any altered form, except for review purposes. All ship, crew and other game piece names and representations remain the property of WizKids. Portions of this guide have previously appeared on the website Pojo.com in a slightly altered form. All Prices Listed are current as of June 2006 and are representative of new “mint- condition” game pieces. Email me at [email protected] Visit my home page at www.geocities.com/wmnoe Join me at www.pojo.com WildWill would like to thank: WizKids Games, Pojo.com, Monica Lond-LeBlanc, Bill ‘Pojo’ Gill, James and Robin Hurwitz, Pat Pritchett, Stephanie Veglia.and Wendy Harrison Special Thanks to all my instructors and TA’s at UCLA from 2004 to 2006, especially: Joseph DiMuro, Michael Allen, Sean Silver, Noah Comet, Lars Larsen, Helen Deutsch and Irene Beesemyer Extra Special Thanks to my loving wife Melissa Pritchett, whom I cannot live without. -

Colonialism, Maasina Rule, and the Origins of Malaitan Kastom

Colonialism, Maasina Rule, and the Origins of Malaitan Kastom Pacific Islands Monograph Series 26 Colonialism, Maasina Rule, and the Origins of Malaitan Kastom David W. Akin Center for Pacific Islands Studies School of Pacific and Asian Studies University of Hawai‘i, Mānoa University of Hawai‘i Press • Honolulu © 2013 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Akin, David, [date–] author. Colonialism, Maasina rule, and the origins of Malaitan kastom / David Akin. pages cm. — (Pacific islands monograph series ; 26) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8248-3814-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Malaita Province (Solomon Islands)—Politics and government. 2. Malaita Province (Solomon Islands)—Social life and customs. 3. Self-determination, National—Solomon Islands. I. Title. II. Series: Pacific islands monograph series ; no. 26. DU850.A684 2013 995.93’7—dc23 2013008708 Maps by Manoa Mapworks, Inc. University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Design by University of Hawai‘i Press Design & Production Department Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc. To Ma‘aanamae, Sulafanamae, and Saetana ‘Ola moru siria lo‘oo, fu‘u wane. and Kisini CENTER FOR PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I Terence Wesley-Smith, Director PACIFIC ISLANDS MONOGRAPH SERIES Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, General Editor Jan Rensel, Managing Editor EDITORIAL BOARD Hokulani Aikau Alex Golub David Hanlon Robert C Kiste Jane Freeman Moulin Puakea Nogelmeier Lola Quan Bautista Ty Kāwika Tengan The Pacific Islands Monograph Series is a joint effort of the University of Hawai‘i Press and the Center for Pacific Islands Studies, University of Hawai‘i. -

74- %2-42 4264

G. ELGIN. Pistol Sword. No. 254. Patented July 5, 1837. Zerezz/ W22ze war. 774 7/24 74- %2-42 4264 PEERS, photo-LTHOGRAPHER, washingtoN, d. c. UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. GEO. ELGIN, OF NEW YORK, N. Y. MPROVEMENT IN THE PSTOL KNIFE OR C UTASS. Specification forming part of Letters Patent No. 254, dated July 5, 1887. s To all tuhon, it inval? concern: m I construct my pistols, knives, and cutlasses Be it known that I, GEORGE ELGIN, of the in any of the known forms, and combine them city, county, and State of New York, late of in the following manner: The handle being the city of Macon, county of Bibb and State the same, the barrel and blade are combined of Georgia, have invented a new and useful by tongue and groove with a screw or screws, instrument called the Pistol-Knife or Pistol or the barrel and blade can be made solid, or Cutlass; and I do hereby declare that the foll the two can be soldered in such manner as to lowing is a true and exact description. be firm and Substantial. The barrel is com The nature of my invention consists in com bined on the top or back of the knife or cut bining the pistol and Bowie knife, or the pis lass, and may extend to any distance to suit tol and cutlass, in such manner that it can be the maker or manufacturer. used with as much ease and facility as either What I claim as my invention, and desire the pistol, knife, or cutlass could be if sepa to secure by Letters Patent, is rate, and in an engagement, when the pistol The combination of the pistol and blade in is discharged, the knife (or cutlass) can be the manner above described, using any metals brought into immediate use without changing for the manufacture of those articles which or drawing, as the two instruments are in the will produce the intended effect. -

Pirate Word List

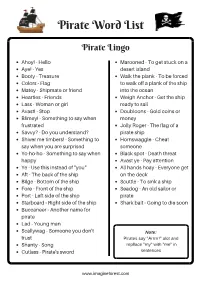

Pirate Word List Pirate Lingo Ahoy! - Hello Marooned - To get stuck on a Aye! - Yes desert island Booty - Treasure Walk the plank - To be forced Colors - Flag to walk off a plank of the ship Matey - Shipmate or friend into the ocean Hearties - Friends Weigh Anchor - Get the ship Lass - Woman or girl ready to sail Avast! - Stop Doubloons - Gold coins or Blimey! - Something to say when money frustrated Jolly Roger - The flag of a Savvy? - Do you understand? pirate ship Shiver me timbers! - Something to Hornswaggle - Cheat say when you are surprised someone Yo-ho-ho - Something to say when Black spot - Death threat happy Avast ye - Pay attention Ye - Use this instead of "you" All hands hoay - Everyone get Aft - The back of the ship on the deck Bilge - Bottom of the ship Scuttle - To sink a ship Fore - Front of the ship Seadog - An old sailor or Port - Left side of the ship pirate Starboard - Right side of the ship Shark bait - Going to die soon Buccaneer - Another name for pirate Lad - Young man Scallywag - Someone you don't Note: trust Pirates say "Arrrrr!" alot and Shanty - Song repllace "my" with "me" in Cutlass - Pirate's sword sentences www.imagineforest.com Word Bank abandon contraband hijack plank skull and bones adventure crew hook prowl steal anchor criminal horizon quarters swagger ashore crook hostile quest swashbuckling assault cruel hurricane raid sword attack curse illegal rat thief bad cutthroat infamous rations vandalize bandanna dagger island revenge vanquish bandit danger jewels riches vicious barbaric deck kidnap roam -

Shiver Me Timbers! by Cap’N Tim Huckelbery

Shiver me Timbers! By Cap’n Tim Huckelbery The blasted city of Mordheim has called to many opportunity to join the pirate crew (usually at a Pirate Captain with the song of easy riches, as the point of a cutlass!). As an alternative to the nearby rivers are filled with ships laden with exchanging/ransoming the captured Hero back either gold into the city or departing with to their original Warband (or selling him to wyrdstone. Using the perpetual fog and dust slavers), the Pirate Captain can instead add the which fills the air around the ruins, a ship can captured enemy to the ship’s crew as follows. navigate the city via the deep rivers running Both players roll 2D6, with the Pirate player though it. With lightning speed, the pirate ships adding the Captain’s Leadership and the enemy can appear from nowhere and attack a ship, player adding the Leadership of the captured quickly looting it of any valuables. Some Hero. If either side won that game, it may add Captains have even found safe harbours for +1 to it’s score. their vessels, and lead frequent raiding parties If the Pirate player’s result is higher, the Hero into the city itself. These brave pirate bands renounces his old ways for the life of the high have become new additions to other groups of seas! She or he joins the Crew, either starting a adventurers, fanatics, and nightmare creatures new Crew group or joining an existing one if it that dare enter the remains of the City of the has four models or less.