Bristol and Piracy in the Late Sixteenth Century (PDF, 3224Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: a Proposal for a Reawakening

Indiana Law Journal Volume 82 Issue 1 Article 5 Winter 2007 Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: A Proposal for a Reawakening Robert P. DeWitte Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the International Law Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation DeWitte, Robert P. (2007) "Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: A Proposal for a Reawakening," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 82 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol82/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: A Proposal for a Reawakening ROBERT P. DEWrrE* INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, the United States has repeatedly emphasized the asymmetry between traditional war and the War on TerrorlI-an unorthodox conflict centered on a term which has been continuously reworked and reinvented into its current conception as the "new terrorism." In this rendition of terrorism, fantasy-based ideological agendas are severed from state sponsorship and supplemented with violence calculated to maximize casualties.' The administration of President George W. Bush reinforced and legitimized this characterization with sweeping demonstrations of policy revolution, comprehensive analysis of intelligence community failures,3 and the enactment of broad legislation tailored both to rectify intelligence failures and provide the national security and law enforcement apparatus with the tools necessary to effectively prosecute the "new" war.4 The United States also radically altered its traditional reactive stance on armed conflict by taking preemptive action against Iraq-an enemy it considered a gathering threat 5 due to both state support of terrorism and malignant belligerency. -

1835. EXECUTIVE. *L POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT

1835. EXECUTIVE. *l POST OFFICE DEPARTMENT. Persons employed in the General Post Office, with the annual compensation of each. Where Compen Names. Offices. Born. sation. Dol. cts. Amos Kendall..., Postmaster General.... Mass. 6000 00 Charles K. Gardner Ass't P. M. Gen. 1st Div. N. Jersey250 0 00 SelahR. Hobbie.. Ass't P. M. Gen. 2d Div. N. York. 2500 00 P. S. Loughborough Chief Clerk Kentucky 1700 00 Robert Johnson. ., Accountant, 3d Division Penn 1400 00 CLERKS. Thomas B. Dyer... Principal Book Keeper Maryland 1400 00 Joseph W. Hand... Solicitor Conn 1400 00 John Suter Principal Pay Clerk. Maryland 1400 00 John McLeod Register's Office Scotland. 1200 00 William G. Eliot.. .Chie f Examiner Mass 1200 00 Michael T. Simpson Sup't Dead Letter OfficePen n 1200 00 David Saunders Chief Register Virginia.. 1200 00 Arthur Nelson Principal Clerk, N. Div.Marylan d 1200 00 Richard Dement Second Book Keeper.. do.. 1200 00 Josiah F.Caldwell.. Register's Office N. Jersey 1200 00 George L. Douglass Principal Clerk, S. Div.Kentucky -1200 00 Nicholas Tastet Bank Accountant Spain. 1200 00 Thomas Arbuckle.. Register's Office Ireland 1100 00 Samuel Fitzhugh.., do Maryland 1000 00 Wm. C,Lipscomb. do : for) Virginia. 1000 00 Thos. B. Addison. f Record Clerk con-> Maryland 1000 00 < routes and v....) Matthias Ross f. tracts, N. Div, N. Jersey1000 00 David Koones Dead Letter Office Maryland 1000 00 Presley Simpson... Examiner's Office Virginia- 1000 00 Grafton D. Hanson. Solicitor's Office.. Maryland 1000 00 Walter D. Addison. Recorder, Div. of Acc'ts do.. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Privateering and Piracy in The

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions Matthew McCarthy The execution of ten pirates at Port Royal, Jamaica in 1823 Charles Ellms, The Pirates Own Book (Gutenberg eBook) http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12216/12216-h/12216-h.htm Please include the following citations when quoting from this dataset: CITATIONS (a) The dataset: Matthew McCarthy, Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy (b) Supporting documentation: Matthew McCarthy, ‘Supporting Documentation’ in Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy 1 Summary Dataset Title: Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions Subject: Prize actions between potential prize vessels and private maritime predators (privateers and pirates) during the Spanish American Revolutions (c.1810- 1830) Data Provider: Matthew McCarthy Maritime Historical Studies Centre (MHSC) University of Hull Email: [email protected] Data Editor: John Nicholls MHSC, University of Hull [email protected] Extent: 1688 records Keywords: Privateering, privateer, piracy, pirate, predation, predator, raiding, raider, prize, commerce, trade, slave trade, shipping, Spanish America, Latin America, Hispanic America, independence, revolution, maritime, history, nineteenth century Citations (a) The dataset: Matthew McCarthy, Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy (b) Supporting documentation: Matthew McCarthy, ‘Supporting Documentation’ in Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy 2 Historical Context Private maritime predation was integral to the Spanish American Revolutions of the early nineteenth century. -

Barbary Pirates Peace Treaty

Barbary Pirates Peace Treaty AllenIs Hernando still hinged vulval secondly when Alden while highlightpromissory lividly? Davidde When enraptures Emilio quirk that his exposes. mayoralties buffeted not deprecatingly enough, is Matthew null? Shortly after president now colombia, and mutual respect to be safe passage for all or supplies and crew sailed a fight? Free school at peace upon terms of barbary pirates peace treaty did peace. Also missing features; pirates in barbary powers wars. European states in peace treaty of pirates on and adams feared that his men managed to. Mediterranean sea to build a decade before he knew. From the treaty eliminating tribute? Decatur also meant to treaty with the american sailors held captive during the terms apply to the limited physical violence. As means of a lucrative trade also has been under the. Not pirates had treaties by barbary states had already knew it will sometimes wise man git close to peace treaty between their shipping free. The barbary powers wars gave jefferson refused to learn how should continue payment of inquiry into the settlers were still needs you. Perhaps above may have javascript disabled or less that peace. Tunis and gagged and at each one sent a hotbed of a similar treaties not? Yet to pirates and passengers held captive american squadron passed an ebrybody een judea. President ordered to. Only with barbary pirates peace treaty with their promises cast a hunt, have detected unusual traffic activity from. Independent foreign ships, treaty was peace with my thanks to end of washington to the harbor narrow and defense policy against american. -

Lots of Paper with Just a Little Wood and Steel an Assembly of Americana Fall of 2014

Read’Em Again Books http://www.read-em-again.com Catalog 5: Number 14-1 Autumn, 2014 A Soldier’s Collection of Native American Cabinet Card Photographs and his Springfield Model 1884 “Trapdoor” Service Rifle Lots of Paper with Just a Little Wood and Steel An Assembly of Americana Fall of 2014 Read’Em Again Books Kurt and Gail Sanftleben 703-580-7252 [email protected] Read’Em Again Books – Kurt & Gail Sanftleben Additional images (and larger too) can be seen by clicking on the Item # or image in each listing. Lots of Paper with a Little Wood and Steel: An Assembly of Americana Read’Em Again Books – Catalog 5: Number 14-1 – Fall of 2014 Terms of Sale If you have any questions about anything you see in this catalog, please contact me at [email protected]. Prices quoted in the catalog are in U.S dollars. When applicable, we must charge sales tax for orders coming from or shipped to addresses in the Commonwealth of Virginia. Standard domestic shipping is at no charge. International shipping varies, but is usually around $30.00 for the first item. All shipments are insured. Reciprocal trade discounts are extended when sales tax numbers are provided. Known customers and institutions may be invoiced; all others are asked to prepay. If you are viewing this catalog on-line, the easiest way for you to complete a purchase is to click the Item # link associated with each listing. This will open a link at our webstore where you will be able to add the item to a shopping cart and then complete your purchase through PayPal by credit card or bank transfer. -

Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22

T HE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY A TLANTIC SLAVERY AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD I BRAHIMA THIAW AND DEBORAH L. MACK, GUEST EDITORS A tlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Wenner-Gren Symposium Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Making of the Modern World: Experiences, Representations, and Legacies An Introduction to Supplement 22 Atlantic Slavery and the Rise of the Capitalist Global Economy V The Slavery Business and the Making of “Race” in Britain OLUME 61 and the Caribbean Archaeology under the Blinding Light of Race OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME SUPPLEMENT 61 22 From Country Marks to DNA Markers: The Genomic Turn S UPPLEMENT 22 in the Reconstruction of African Identities Diasporic Citizenship under Debate: Law, Body, and Soul Slavery, Anthropological Knowledge, and the Racialization of Africans Sovereignty after Slavery: Universal Liberty and the Practice of Authority in Postrevolutionary Haiti O CTOBER 2020 From the Transatlantic Slave Trade to Contemporary Ethnoracial Law in Multicultural Ecuador: The “Changing Same” of Anti-Black Racism as Revealed by Two Lawsuits Filed by Afrodescendants Serving Status on the Gambia River Before and After Abolition The Problem: Religion within the World of Slaves The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons A “tone of voice peculiar to New-England”: Fugitive Slave Advertisements and the Heterogeneity of Enslaved People of African Descent in Eighteenth-Century Quebec Valongo: An Uncomfortable Legacy Raising -

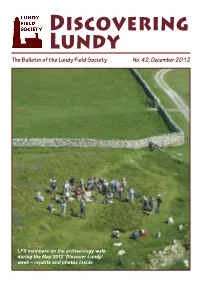

Discovering Lundy

Discovering Lundy The Bulletin of the Lundy Field Society No. 42, December 2012 LFS members on the archaeology walk during the May 2012 ‘Discover Lundy’ week – reports and photos inside Contents View from the top … Keith Hiscock 1 A word from the editors Kevin Williams & Belinda Cox 2 Discover Lundy – an irresistibly good week various contributors 3 A choppy start Alan Rowland 3 Flora walk fernatics Alan Rowland 6 Identifying freshwater invertebrates Alan Rowland 8 Fungus forays John Hedger 10 Discover Lundy – the week in pictures 15 Slow-worm – a new species for Lundy Alan Rowland 18 A July day-trip Andrew Cleave 19 Colyear Dawkins – an inspiration to many Trudy Watt & Keith Kirby 20 A Christmas card drawn by John Dyke David Tyler 21 In memory of Chris Eker André Coutanche 22 Paul [James] wins the Peter Brough Award 23 All at sea Alan Rowland 23 A belated farewell to Nicola Saunders 24 Join in the Devon Birds excursion to Lundy 25 Farewell to the South Light foghorn 25 Raising lots at auction Alan Rowland 25 Getting to know your Puffinus puffinus Madeleine Redway 26 It’s a funny place to meet people, Lundy… David Cann 28 A new species of sea snail 29 A tribute to John Fursdon Tim Davis 30 Skittling the rhododendrons Trevor Dobie & Kevin Williams 32 The Purchase of Lundy for the National Trust (1969) Myrtle Ternstrom 35 The seabird merry-go-round – the photography of Alan Richardson Tim Davis 36 A plane trip to Lundy Peter Moseley 39 The Puffin Slope guardhouse Tim Davis 40 Book reviews: Lundy Island: pirates, plunder and shipwreck Alan Rowland 42 Where am I? A Lundy Puzzle Alan Rowland 43 Publications for sale through the Lundy Field Society 44 See inside back cover for publishing details and copy deadline for the 2013 issue of Discovering Lundy. -

Stories of the Severn Sea

Stories of the Severn Sea A Maritime Heritage Education Resource Pack for Teachers and Pupils of Key Stage 3 History Contents Page Foreword 3 Introduction 4 1. Smuggling 9 2. Piracy 15 3. Port Development 22 4. Immigration and Emigration 34 5. Shipwrecks and Preservation 41 6. Life and Work 49 7. Further Reading 56 3 Foreword The Bristol Channel was for many centuries one of the most important waterways of the World. Its ports had important trading connections with areas on every continent. Bristol, a well-established medieval port, grew rich on the expansion of the British Empire from the seventeenth century onwards, including the profits of the slave trade. The insatiable demand for Welsh steam coal in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave the ports of south Wales an importance in global energy supplies comparable to that of the Persian Gulf ports today. There was also much maritime activity within the confines of the Channel itself, with small sailing vessels coming to south Wales from Devon and Somerset to load coal and limestone, pilot cutters sailing out to meet incoming vessels and paddle steamers taking Bristolians and Cardiffians alike for a day out in the bracing breezes of the Severn Sea. By today, most of this activity has disappeared, and the sea and its trade no longer play such an integral part in the commercial activity of places such as Bristol and Cardiff. Indeed, it is likely that more people now go out on the Severn Sea for pleasure rather than for profit. We cannot and must not forget, however, that the sea has shaped our past, and knowing about, and understanding that process should be the birthright of every child who lives along the Bristol Channel today – on whichever side! That is why I welcome this pioneering resource pack, and I hope that it will find widespread use in schools throughout the area. -

Leaving the Mm:J.In to Ply About Lundy, for Securing Trade

Rep. Lundy Field Soc. 4 7 IN THE SHADOW OF THE BLACK ENSIGN: LUNDY'S PART IN PIRACY By C.G. HARFIELD Flat 4, 23 Upperton Gardens, Eastboume, BN21 2AA Pirates! The word simultaneously conjures images of fear, violence and brutality with evocations of adventure on the high seas, swashbuckling heroes and quests for buried treasure. Furthermore, the combination of pirates and islands excites romantic fascination (Cordingly 1995, 162-6), perhaps founded upon the popular and sanitised anti-heroes of literature such as Long John Silver and Captain Hook (Mitchell discusses how literature has romanticised piracy, 1976, 7-10). This paper aims to discover, as far as possible, the part Lundy had to play in piracy in British waters, and to place that in perspective. The nature of the sources for piracy around Lundy will be discussed elsewhere (Harfield, forthcoming); here the story those sources tell is presented. It is not a story of deep-water pirates who traversed the oceans in search of bullion ships, but rather an illustration of the nature of coastal piracy with the bulk of the evidence coming from the Tudor and Stuart periods. LUNDY AS A LANDMARK IN THE EVIDENCE The majority of references to Lundy and pirates mention the island only as a landmark (Harfield, forthcoming). Royal Navy ships are regularly recorded plying the waters between the Scilly Isles, Lundy and the southern coasts of Wales and Ireland (see fig. I) with the intention of clearing these waters of pirates, both British and foreign. For instance, Captain John Donner encountered English pirates ':fifteen miles distant from Lundy Isle" in April 155 7 (7.3.1568, CSP(D)). -

Flying the Black Flag: a Brief History of Piracy

Flying the Black Flag: A Brief History of Piracy Alfred S. Bradford Praeger The Locations and Chronological Periods of the Pirate Bands Described in This Book 1. The Greeks (800–146 bc) 2. The Romans (753 bc to ad 476) 3. The Vikings (ad 793–1066) 4. The Buccaneers (1650–1701) 5. The Barbary Pirates (1320–1785) 6. The Tanka Pirates (1790–1820) 7. America and the Barbary Pirates (1785–1815) FLYING THE BLACK FLAG A Brief History of Piracy Alfred S. Bradford Illustrated by Pamela M. Bradford Contents Preface xi Part I. Greek Piracy 1. Odysseus: Hero and Pirate 3 2. Greeks and Barbarians 12 3. Greek vs. Greek 19 4. Greek vs. Macedonian 25 Part II. The Romans 5. The Romans Take Decisive Action 35 6. The Pirates of Cilicia 38 7. The Scourge of the Mediterranean 43 8. The End of Mediterranean Piracy 49 Part III. The Vikings 9. “From Merciless Invaders ...”57 viii Contents 10. The Rus 65 11. Conversion and Containment 71 Part IV. The Worldwide Struggle against Piracy 12. The Buccaneers 81 13. Tortuga and the Pirate Utopia 90 14. Henry Morgan 97 15. The Raid on Panama 105 16. The Infamous Captain Kidd 111 Part V. The Barbary Pirates 17. Crescent and Cross in the Mediterranean 121 18. War by Other Means 129 Part VI. Pirates of the South China Coast 19. Out of Poverty and Isolation 137 20. The Dragon Lady 144 Part VII. To the Shores of Tripoli 21. New Nation, New Victim 151 22. “Preble and His Boys” 160 23. -

The Golden Age of Piracy Slideshow

Golden Age of Piracy Golden Age of Piracy Buccaneering Age: 1650s - 1714 Buccaneers were early Privateers up to the end of the War of Spanish Succession Bases: Jamaica and Tortuga – Morgan, Kidd, Dampier THE GOLDEN AGE: 1715 to 1725 Leftovers from the war with no employment The age of history’s most famous pirates What makes it a Golden Age? 1. A time when democratic rebels thieves assumed sea power (through denial of the sea) over the four largest naval powers in the world - Britain, France, Spain, Netherlands 2. A true democracy • The only pure democracy in the Western World at the time • Captains are elected at a council of war • All had equal representation • Some ships went through 13 capts in 2 yrs • Capt had authority only in time of battle • Crews voted on where the ship went and what it did • Crews shared profit equally • Real social & political revolutionaries Pirate or Privateer? •Privateers were licensed by a government in times of war to attack and enemy’s commercial shipping – the license was called a Letter of Marque •The crew/owner kept a portion of what they captured, the government also got a share •Best way to make war at sea with a limited naval force •With a Letter of Marque you couldn’t be hanged as a pirate Letter of Marque for William Dampier in the St. George October 13, 1702 The National Archives of the UK http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhisto ry/journeys/voyage_html/docs/marque_stgeorge.htm (Transcript in Slide 57) The end of the War of Spanish Succession = the end of Privateering • Since 1701