Pub Crawling at Scale: Tapping Untappd to Explore Social Drinking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drinkerdrinker

FREE DRINKERDRINKER Volume 41 No. 3 June/July 2019 The Anglers, Teddington – see page 38 WETHERSPOON OUR PARTNERSHIP WITH CAMRA All CAMRA members receive £20 worth of 50p vouchers towards the price of one pint of real ale or real cider; visit the camra website for further details: camra.org.uk Check out our international craft brewers’ showcase ales, featuring some of the best brewers from around the world, available in pubs each month. Wetherspoon also supports local brewers, over 450 of which are set up to deliver to their local pubs. We run regular guest ale lists and have over 200 beers available for pubs to order throughout the year; ask at the bar for your favourite. CAMRA ALSO FEATURES 243 WETHERSPOON PUBS IN ITS GOOD BEER GUIDE Editorial London Drinker is published on behalf of the how CAMRA’s national and local Greater London branches of CAMRA, the campaigning can work well together. Of Campaign for Real Ale, and is edited by Tony course we must continue to campaign Hedger. It is printed by Cliffe Enterprise, Eastbourne, BN22 8TR. for pubs but that doesn’t mean that we DRINKERDRINKER can’t have fun while we do it. If at the CAMRA is a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee and registered in England; same time we can raise CAMRA’s profile company no. 1270286. Registered office: as a positive, forward-thinking and fun 230 Hatfield Road, St. Albans, organisation to join, then so much the Hertfordshire AL1 4LW. better. Material for publication, Welcome to a including press The campaign will be officially releases, should preferably be sent by ‘Summer of Pub’ e-mail to [email protected]. -

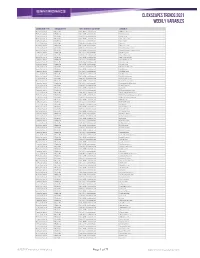

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Systematic Scoping Review on Social Media Monitoring Methods and Interventions Relating to Vaccine Hesitancy

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy www.ecdc.europa.eu ECDC TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy This report was commissioned by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and coordinated by Kate Olsson with the support of Judit Takács. The scoping review was performed by researchers from the Vaccine Confidence Project, at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (contract number ECD8894). Authors: Emilie Karafillakis, Clarissa Simas, Sam Martin, Sara Dada, Heidi Larson. Acknowledgements ECDC would like to acknowledge contributions to the project from the expert reviewers: Dan Arthus, University College London; Maged N Kamel Boulos, University of the Highlands and Islands, Sandra Alexiu, GP Association Bucharest and Franklin Apfel and Sabrina Cecconi, World Health Communication Associates. ECDC would also like to acknowledge ECDC colleagues who reviewed and contributed to the document: John Kinsman, Andrea Würz and Marybelle Stryk. Suggested citation: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020. Stockholm, February 2020 ISBN 978-92-9498-452-4 doi: 10.2900/260624 Catalogue number TQ-04-20-076-EN-N © European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the -

Breaking Trust: Shades of Crisis Across an Insecure Software Supply Chain #Accyber

Breaking Trust: Shades of Crisis Across an Insecure Software Supply Chain #ACcyber CYBER STATECRAFT INITIATIVE BREAKING TRUST: Shades of Crisis Across an Insecure Software Supply Chain Trey Herr, June Lee, William Loomis, and Stewart Scott Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. Cyber Statecraft Initiative The Cyber Statecraft Initiative works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology. This work extends through the competition of state and non-state actors, the security of the internet and computing systems, the safety of operational technology and physical systems, and the communities of cyberspace. The Initiative convenes a diverse network of passionate and knowledgeable contributors, bridging the gap among technical, policy, and user communities. CYBER STATECRAFT INITIATIVE BREAKING TRUST: Shades of Crisis Across an Insecure Software Supply Chain Trey Herr, June Lee, William Loomis, and Stewart Scott ISBN-13: 978-1-61977-112-3 Cover illustration: Getty Images/DavidGoh This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The author is solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. -

How Location-Based Social Network Applications Are Being Used

Sean David Brennan HOW LOCATION-BASED SOCIAL NETWORK APPLICATIONS ARE BEING USED JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO TIETOJENKÄSITTELYTIETEIDEN LAITOS 2015 ABSTRACT Brennan, Sean David How Location-Based Social Network Applications Are Being Used Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2015, 60 p. Information Systems Science, Master’s Thesis Supervisor: Veijalainen, Jari Location-based social network applications have globally become very popular with the expansion of smartphone usage. Location-based social networks (LBSN) can be defined as a site that uses Web 2.0 technology, GPS, WiFi positioning or mobile devices to allow people to share their locations, which is referred to commonly as a check-in, and to connect with their friends, find places of interest, and leave reviews or tips on specific venues. The aim of this study was to examine how location-based social applications are being used. The methods of this study comprised of a literature review and a discussion on prior research based on a selection of user studies on location-based social networks. This study also aimed at answering a number of sub-questions on user behavior such as activity patterns, motivations for sharing location, privacy concerns, and current and future trends in the field. Twelve LBSN user behavior studies were reviewed in this study. Eight of the user studies reviewed involved the application Foursquare. Research methods on eight of the reviewed studies were studies utilizing databases of the check-ins from the application itself or utilizing Twitter in their analysis. Four of the reviewed studies were user studies involving interviews and surveys. Three main themes emerged from the articles, which were activity patterns, motivations for sharing, and privacy concerns. -

Virtual Classroom Challenges Amid Pandemic for Future Teachers

The Gonzaga Bulletin A student publication of Gonzaga University DECEMBER 3, 2020 www.gonzagabulletin.com VOL. 132 ISSUE 15 Virtual classroom challenges amid pandemic for future teachers By NATALIE RIETH ue to COVID-19 restrictions, Gonzaga Dstudents enrolled in the special education classroom placement and classroom management courses have had to face a delayed classroom placement within schools local to the Spokane area. This set- back has given students the unique opportunity of observing challenges faced by students and teachers within the special education classroom as a result of the pandemic. Before receiving their placement, students were required to complete a virtual module, where they were introduced to online teaching styles and virtual educational platforms, as a part of the 30 hours they must complete observing their assigned classroom. With a mix of students placed in in-person and remote classrooms, students have been able to reflect on the effects the pandemic has had within special education classrooms in each COVID-19 learning environment. Sarah Merlino, a student enrolled in both special education courses, attends BULLETIN FILE PHOTO SEE TEACHERS PAGE 2 GU grad, Lexi Rutherford, student teaches a second grade classroom at St. Aloysius Catholic School in 2016. Gonzaga says goodbye to three key staff members By KAYLA FREIDRICH During the last couple of months, Gonzaga University has seen the resignation of many high positions in multiple offices and is left with the task of figuring out what to do with these positions moving forward. Kelly Alvarado-Young, Amy Swank and Richard Menard have all made significant contributions to their respective departments during their time at GU. -

Chapter 2: Literature Review 19

Value impact of social media: a perspective from the independent brewery sector GODSON, Mark St John Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/25371/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/25371/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Value impact of social media: A perspective from the independent brewery sector Mark St John Godson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Business Administration December 2018 ii Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.1: Introduction - What is this Study About? 1 1.2: Why is this of Interest from a Research Perspective? 3 1.2.1: Background to the independent brewery sector 3 1.2.2: Topicality of social media 4 1.2.3: Personal interests of the researcher 5 1.3: Research Aims, Objectives and Questions 6 1.4: Conducting the Research 8 1.5: Expected Contribution to Knowledge and Practice 8 1.6: Supporting Literature 14 1.7: Structure of Thesis 16 Chapter 2: Literature Review 19 2.1: Introduction 19 2.1.1: Literature review method -

Row Labels Count of Short Appname Mobileiron 3454 Authenticator 2528

Row Labels Count of Short AppName MobileIron 3454 Authenticator 2528 Adobe Reader 916 vWorkspace 831 Google Maps 624 YouTube 543 iBooks 434 BBC iPlayer 432 Facebook 427 Pages 388 WhatsApp 357 FindMyiPhone 313 Skype 303 BBC News 292 Twitter 291 Junos Pulse 291 Numbers 289 TuneIn Radio 284 Keynote 257 Google 243 ITV Player 234 BoardPad 219 Candy Crush 215 Tube Map 211 Zipcar 209 Bus Times 208 mod.gov 205 4oD 193 Podcasts 191 LinkedIn 177 Google Earth 172 eBay 164 Yammer 163 Citymapper 163 Lync 2010 158 Kindle 157 TVCatchup 153 Dropbox 152 Angry Birds 147 Chrome 143 Calculator 143 Spotify 137 Sky Go 136 Evernote 134 iTunes U 132 FileExplorer 129 National Rail 128 iPlayer Radio 127 FasterScan 125 BBC Weather 125 FasterScan HD 124 Gmail 123 Instagram 116 Cleaner Brent 107 Viber 104 Find Friends 98 PDF Expert 95 Solitaire 91 SlideShark 89 Netflix 89 Dictation 89 com.amazon.AmazonUK 88 Flashlight 81 iMovie 79 Temple Run 2 77 Smart Office 2 74 Dictionary 72 UK & ROI 71 Journey Pro 71 iPhoto 70 TripAdvisor 68 Guardian iPad edition 68 Shazam 67 Messenger 65 Bible 64 BBC Sport 63 Rightmove 62 London 62 Sky Sports 61 Subway Surf 60 Temple Run 60 Yahoo Mail 58 thetrainline 58 Minion Rush 58 Demand 5 57 Documents 55 Argos 55 LBC 54 Sky+ 51 MailOnline 51 GarageBand 51 Calc 51 TV Guide 49 Phone Edition 49 Translate 48 Print Portal 48 Standard 48 Word 47 Skitch 47 CloudOn 47 Tablet Edition 46 MyFitnessPal 46 Bus London 46 Snapchat 45 Drive 42 4 Pics 1 Word 41 TED 39 Skyscanner 39 SoundCloud 39 PowerPoint 39 Zoopla 38 Flow Free 38 Excel 38 Radioplayer -

Herding in Untappd Ratings

Guided by the crowd: herding in Untappd ratings Silvan B.P. Mensink 940802558020 April 2020 MCB-70424 Supervisor: Dr. Nikita Sharda Marketing and Consumer Behaviour Group Second reader: Dr.ir. Frans J.H.M. Verhees Marketing and Consumer Behaviour Group Copyright No part of this publication may be reproduced or published in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the head of the Marketing and Consumer Behaviour Group of Wageningen University, The Netherlands. Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Literature background ......................................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Antecedents of herding effects in online communities: WOM and eWOM ................................ 7 2.2. Formation of herding effects in online community platforms ...................................................... 9 2.3. Hypotheses development ............................................................................................................ 11 2.3.1. Direction of prior ratings on subsequent ratings in Untappd ............................................... 11 2.3.2. Direction of prior ratings on subsequent ratings -

Social Media?

Social Media? According to Merriam-Webster, Social Media are : forms of electronic communication (such as websites for social networking and microblogging) through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content (such as pictures and videos) But what does this actually mean? Social media are websites or apps (or both) that allow you to share things with other people. On some sites you can post anonymously and you have as many accounts as you want (Twitter, Tumblr). Other sites limit you to a single personal account and you may have to prove your identity (Facebook, LinkedIn). Some types of social media are for sharing things with one or a few friends (WhatsApp) while others are for broadcasting to the world (Reddit, Pinterest) Social Media by Type Primarily a website YouTube, Facebook, LinkedIn, Reddit, Pinterest, Tumblr Primarily a phone app WhatsApp, Snapchat, Instagram, Signal, Telegram Primarily text Twitter Primarily photos Instagram, Snapchat, Pinterest Primarily one-on-one WhatsApp, Snapchat, Signal, Telegram Primarily public Reddit, YouTube, Tumblr, Pinterest, Tik-Tok Real names / numbers Facebook, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, Signal Anonymous Reddit, Twitter, Tumblr, Pinterest, YouTube, Instagram, Tik-Tok Family & friends Facebook, WhatsApp, Snapchat, Skype, Signal, Telegram Strangers Twitter, Reddit, YouTube, Tumblr, Tik-Tok What Social Media Apps Should I Use? The answer to this is “what do you want to do?” Do you want to keep up with friends and family? Learn about new books being published? Keep on top of political events? Find and organize future projects? How you want to use social media is the main determinant of what social media you’ll want to try. -

Ocean Rising the QUEST to INSPIRE the PUBLIC Ocean Rising

Ocean Rising THE QUEST TO INSPIRE THE PUBLIC Ocean Rising Ocean Rising THE QUEST TO INSPIRE THE PUBLIC INTRODUCTION Our modern world came to a standstill in 2020, with the global COVID-19 pandemic pausing the fast-paced existence many of us led and proving unequivocally that existential threats are not just the stuff of Hollywood disaster movies. What steps would humanity have taken if we had known years in advance the turmoil that 2020 would unleash? We can’t change our past, but we can, with global knowledge and awareness, act to create a harmonious and healthy future. While often not at the forefront of conversation on the global stage, our ocean is the backbone of climate and life on this planet. Every day we see signs of its impact - in our weather, in nature, along our coasts. It is used to transport goods across our globe, feed more than half the population, and keep humans breathing. The ocean is a magnificent resource that quietly gives to all, but is taken for granted and rarely recognized for the role it plays in planetary and human health. In order to change this status quo, we need to inspire the public about the ocean as they are inspired by space. -03 What steps would humanity have taken if we had known years in advance the turmoil that 2020 would unleash? Ocean Rising Ocean Rising SPACE AND OCEAN INSPIRATION Technology makes it possible to walk the deepest The two communities have distinct and critical depths of the ocean and see alien marine life differences in how they inspire and engage a broader without leaving your living room; however, there audience (Virmani, 2017). -

Understanding the Implications of Social Media Invisible Responses for Well-Being and Relational Development

Seeing the Invisible: Understanding the Implications of Social Media Invisible Responses for Well-Being and Relational Development by Penny Triệu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Information) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Nicole B. Ellison, Chair Dr. Nancy K. Baym, Microsoft Research Professor Scott W. Campbell Associate Professor Sarita Y. Schoenebeck Penny Triệu [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8394-803X © Penny Triệu 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my nephew and niece, Quân and Vivi. When I inevitably fail to keep up with the latest technology, I will count on you to show me the ways. ii Acknowledgement The best part of doing the PhD for me was about the people and the community whose support I am privileged to count upon, at and beyond University of Michigan. From the moment I start to consider graduate school as a prospective PhD student, I have received generous offers of help and advice from others, a theme that continues to this day. Here goes my best attempt to acknowledge “the village:” Nicole, I have always considered it my immense luck and privilege to have such a brilliant and supportive advisor to guide me through my PhD, from pointing me in the right literature, leaving innumerable edits and comments on all of my drafts, to organizing the best white elephant gift exchanges. You were always so generous with your time, attention, and wisdom with me, and I grew so much from working with you and being your advisee.