Chapter 2: Literature Review 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEDIAS Newsletter No. 36 November 2009

North East Derbyshire Industrial Archaeology Society NEDIAS Newsletter No. 36 – November 2009 Price: £1.00 (Free to Members) Contents: Claymills Victorian Pumping Station ........................................................ 1 Meetings Diary ........................................................ 3 Mesters, Masters and Noble Enterprise ........................................................ 4 Latest News from Calver Weir ........................................................ 7 Pleasley Pit to Miners Hill ........................................................ 8 IA News and Notes ...................................................... 10 ….. And Finally ...................................................... 12 The NEDIAS Visit to Claymills Victorian Pumping Station EDIAS were really privileged to visit Clay N Mills on a “steaming” day in September on a tour arranged by David Palmer, and were admirably and very knowledgeably shown around the site by guides Steve and Roy. Clay Mills is an outstanding Victorian industrial monument. There are four beam engines by Gimson of Leicester 1885, five Lancashire Boilers 1936-1937, an early 20th Century generator house, Victorian workshop & blacksmith’s forge, and numerous other small engines & artefacts. The Claymills Pumping Engines Trust was incorporated in 1993 to promote and preserve for the benefit of the public the nineteenth century Claymills Pumping Station complex including all buildings, engines and equipment at Meadow Lane, Stretton, Burton on Trent. The site was handed over by Severn Trent Water in September 1993 and the group formed a charitable trust to put the group on an official LEFT: David Palmer cracks a valve to start the beam engine - 1 - footing. From October 1993 there have been regular on site working parties, and the NEDIAS visitors can vouch for the tremendous amount of hard work which has been carried out on site by volunteers. Steam was at last raised again in boiler five during December 1998 and ‘C’ engine was first run again in May 2000. -

A Survey of Food Blogs and Videos: an Explorative Study Lynn Schutte University of South Carolina, [email protected]

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College Spring 2018 A Survey of Food Blogs and Videos: An Explorative Study Lynn Schutte University of South Carolina, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Recommended Citation Schutte, Lynn, "A Survey of Food Blogs and Videos: An Explorative Study" (2018). Senior Theses. 229. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/229 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract 2 Introduction 3 Methods 6 Results 7 Discussion 10 References 14 Appendices 15 Appendix 1: Summary Guidelines 15 1.1 Video Summary Guidelines 15 1.2 Blog Summary Guidelines 15 Appendix 2: Codebooks 16 2.1 Video Codebook 16 2.2 Blog Codebook 18 1 Abstract This study aimed to explore what types of food blogs and videos exist, what their common practices are and their popularity levels. Through a content analysis of four videos or posts from 25 different producers or blogs, respectively, a total of 200 pieces of content were coded and analyzed. The coding focused on main ingredients, sponsorship, type of video or post and number of views or comments. It was found that blogs were written for a specific audience, in terms of blog types, while video producers were more multi‑purpose. This could be because of sampling method or because blogs are often sought after, while videos tend to appear in viewers’ timelines. -

Real Ale Experience a Guide to Some of the Much Loved Real Ale Pubs in North Shields and Tynemouth

Real Ale Experience A guide to some of the much loved real ale pubs in North Shields and Tynemouth EDUCATION AND CULTURAL SERVICES Real Ale Experie With traditional pubs offering unrivalled hospitality, each with their own intriguing stories to tell, the Real Ale Experience is a trip for the connoisseur of beers and those who enjoy their inns and taverns with character. The town centre pubs, bustling with charm, have been a focal point of North Shields for centuries, playing a role in the development of the town. Tynemouth has a mix of old and new pubs, providing a fine choice of venues and The Fish Quay, the traditional trading and commercial heart of the town, offers a unique experience where the locals are larger than life and seem more like characters from a seafaring novel. So…prepare to taste the experience for yourself. The Magnesia Bank Camden Street, North Shields The Magnesia Bank stands high on the bank side overlooking the nce historic fish quay and it is worth pausing at the railings at the bottom of Howard Street and enjoying the views of the river before imbibing. The building to the right, marked with a blue plaque, is Maritime Chambers, once the home of the Stag Line and, before that, the Tynemouth Literary and Philosophical Society’s library. The pub itself, originally a Georgian commercial bank, opened in 1989 and quickly established a reputation as a real ale pub, a reputation certainly justified in the number of awards it has won. The pub has developed a worldwide standing for its real ales and proudly serves cask ales in the best condition, a fact acknowledged by the many awards received from the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA). -

Learn How to Use Google Reviews at Your Hotel

Learn How to Use Google Reviews at your Hotel Guide Managing Guest Satisfaction Surveys: Best Practices Index Introduction 2 Can you explain Google’s rating system? 3 What’s different about the new Google Maps? 5 Do reviews affect my hotel’s search ranking? 6 How can we increase the number of Google reviews? 7 Can I respond to Google reviews? 8 Managing Guest Satisfaction1 Surveys: Best Practices Introduction Let’s be honest, Google user reviews aren’t very helpful And then there’s the near-ubiquitous “+1” button, a way when compared to reviews on other review sites. for Google+ users to endorse a business, web page, They’re sparse, random and mostly anonymous. You photo or post. can’t sort them, filtering options are minimal, and the rating system is a moving target. These products are increasingly integrated, allowing traveler planners to view rates, availability, location, But that’s all changing. photos and reviews without leaving the Google ecosystem. Reviews and ratings appear to play an increasingly critical role in Google’s master plan for world domination This all makes Google reviews difficult to ignore—for in online travel planning. They now show prominently in travelers and hotels. So what do hotels need to know? In Search, Maps, Local, Google+, Hotel Finder and the this final instalment in ReviewPro’s popular Google For new Carousel—and on desktops, mobile search and Hotels series, we answer questions from webinar mobile applications. attendees related to Google reviews. Managing Guest Satisfaction2 Surveys: Best Practices Can you Explain Google’s Rating System? (I) Registered Google users can rate a business by visiting its Google+ 360° Guest Local page and clicking the Write a Review icon. -

Drinkerdrinker

FREE DRINKERDRINKER Volume 41 No. 3 June/July 2019 The Anglers, Teddington – see page 38 WETHERSPOON OUR PARTNERSHIP WITH CAMRA All CAMRA members receive £20 worth of 50p vouchers towards the price of one pint of real ale or real cider; visit the camra website for further details: camra.org.uk Check out our international craft brewers’ showcase ales, featuring some of the best brewers from around the world, available in pubs each month. Wetherspoon also supports local brewers, over 450 of which are set up to deliver to their local pubs. We run regular guest ale lists and have over 200 beers available for pubs to order throughout the year; ask at the bar for your favourite. CAMRA ALSO FEATURES 243 WETHERSPOON PUBS IN ITS GOOD BEER GUIDE Editorial London Drinker is published on behalf of the how CAMRA’s national and local Greater London branches of CAMRA, the campaigning can work well together. Of Campaign for Real Ale, and is edited by Tony course we must continue to campaign Hedger. It is printed by Cliffe Enterprise, Eastbourne, BN22 8TR. for pubs but that doesn’t mean that we DRINKERDRINKER can’t have fun while we do it. If at the CAMRA is a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee and registered in England; same time we can raise CAMRA’s profile company no. 1270286. Registered office: as a positive, forward-thinking and fun 230 Hatfield Road, St. Albans, organisation to join, then so much the Hertfordshire AL1 4LW. better. Material for publication, Welcome to a including press The campaign will be officially releases, should preferably be sent by ‘Summer of Pub’ e-mail to [email protected]. -

• E U B , I E B Club of T E Y Ea R a A

Tyneside & Northumberland Branch FREEFREE Issue 235 • Spring 2016 LUB & C OF B T U H P E R Y E E A D I R C A , W B U A P R D E S H T • • 2016 ALL THE WINNERS INSIDE Fortieth Newcastle Beer & Cider Festival Northumbria University Students Union April 2016 Wed 6th 6.00 – 10.30 pm Thu 7th Fri 8th 12.00 – 10.30 pm Sat 9th 12.00 – 5.00 pm Hat Day Thursday The Happy Cats Saturday pm Tyneside & Northumberland Campaign for Real Ale www.cannybevvy.co.uk BRANCH CONTACTS TALKING ED Chairman: Ian Lee First there were the Golden Globes, followed by the BAFTAs, then [email protected] the Oscars and finally the one you have all been waiting for, the POTYs. Yes, the 2016 Tyneside & Northumberland Pub, Cider Pub Secretary: Pauline Chaplain and Club of the Year Awards. To see if your favourite pub, cider [email protected] pub or club has won, then turn to pages 16 & 17 to find out (but Treasurer: Jan Anderson not until you have finished reading the editorial). At present there [email protected] are only four micropubs in the branch area and two of them have won. Congratulations to The Office, Morpeth and The Curfew, Membership Secretary & Social Berwick - which was also the overall Northumberland Pub of the Media Officer: Alan Chaplain Year winner. Remarkably both micropubs have been open for less [email protected] than two years. [email protected] CAMRA has joined forces with brewing trade associations to call Editor, Advertising & Distribution: Adrian Gray for a cut in beer tax in this year’s Budget. -

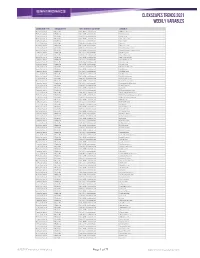

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

The Villager June 19

The Villager The Official Publication of Normandy Parish Council June 2019 - Issue 69 Welcome Welcome to the June 2019 edition of The Villager. I hope you enjoy reading the articles inside. The Local Elections were held on the 2nd May this year when the Parish Council increased its number of councillors from seven to nine. It was uncontested as only nine people put themselves forward for election. You may have noticed that only seven are actually ‘elected’. This is due to Guildford Borough Council having ‘lost’ two sets of paperwork (Val Cheesman and myself). This was corrected at the Parish Council AGM on 15th May. Five of the existing councillors (David Simmons, Ally Lawson, Geoff Doven, Bob Hutton and Peter Palmer) were re-elected plus two new, Margaret Amos and Sarah Noble. Welcome to Sarah and Margaret. Please see inside a few words from Margaret and Sarah by way of introduction. The increase in councillors is no cost to the Village as we are all volunteers (not paid). I would like to take this opportunity to thank all our councillors for all the time and effort they have put in throughout their term of office and hope they will continue to show such dedication through the next term. Also a special thank you to Leslie Clarke, our Parish Clerk, without whose vast knowledge it would make my position extremely difficult and Anna Beuden, our Assistant Clerk, Website and Villager Editor. The Local Plan has been accepted by the Planning Inspector and Guildford Borough Council have put it in place. Normandy has ‘escaped’ from any major developments, but the developed areas of the village will now be inset from the Green Belt. -

Carlisle City Council

CARLISLE CITY COUNCIL Licensing Act 2003 Statement of Licensing Policy For the period 2016-2021 Page 1 1.0 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Purpose of Policy ............................................................................................. 4 3.0 Scope of this policy .......................................................................................... 5 4.0 General matters ................................................................................................ 5 5.0 Licensing objectives…………………………………………………………..……..8 6.0 Personal licences ........................................................................................... 12 7.0 Applications .................................................................................................... 13 8.0 Review of Premises Licence and Other persons ............................................ 16 9.0 Temporary Event Notices (TEN’s) .................................................................. 20 10.0 Live Music Act 2012…………………….………………………………………… 21 11.0 Cumulative Impact Policy ............................................................................... 22 12.0 Late Nigt Levy……………………….…………………………………………… 24 13.0 Early Morning Restriction Orders (EMRO) .................................................... 24 14.0 Enforcement ................................................................................................. 27 15.0 Administration, Exercise and Delegation of functions -

About Cumbria Text and Graphics

Building pride in Cumbria About Cumbria Cumbria is located in the North West of England. Allerdale The County’s western boundary is defined by the Irish Sea and stretches from the Solway Firth down to Incorporating an impressive coastline, rugged Morecambe Bay. It meets Scotland in the North and mountains and gentle valleys, much of which lie the Pennine Hills to the East. It is the second largest within the Lake District National Park, the borough of county in England and covers almost half (48%) of Allerdale covers a large part of Cumbria’s west coast. the whole land area of the North West region. It is Approximately 95,000 people live within the borough generally recognised as an outstandingly beautiful which includes the towns of Workington, Cockermouth area and attracts huge loyalty from local people and and Keswick. visitors from both the British Isles and overseas. Workington, an ancient market town which also has Cumbria’s settlement pattern is distinct and has been an extensive history of industry lies on the coast at dictated principally by its unique topography. The the mouth of the River Derwent. During the Roman large upland area of fells and mountains in the centre occupation of Britain it was the site of one of the means that the majority of settlements are located Emperor Hadrian’s forts which formed part of the on the periphery of the County and cross-county elaborate coastal defence system of the Roman Wall. communications are limited. The town we see today has grown up around the port and iron and steel manufacturing have long Cumbria is home to around 490,000 people. -

Beer Matters

BBBBBB EEREER MATMATTT ERS ERS The magazine of the Campaign for Real Ale (Sheffield & District branch) FREE Circulation 3500 monthly Issue 392 November 2009 www.camra.org.uk/sheffield Every little helps! We celebrate Cider month by helping with the cider making & deliveries at Woodthorpe Hall Saturday 17th October saw us take part in the annual Woodthorpe Hall Cider Run, where we hand deliver a tub of Owd Barker Cider from Woodthorpe Hall in Holmesfield to the Royal Oak pub in Millthorpe, where we had lunch. Then it was back to the Hall, to meet cider maker Dick Shepley and help his volunteers with the cleaning and pressing of apples (plus drink cider & eat cake!) Brewery news 3 Abbeydale Brewery kidding! Abbeydale’s At Bradfield Brewery the run up to the Special for festive season starts mid October when we November is brew the first of our seasonal specials Jack Chocolate O’Lantern at 4.5% ABV this dark amber Stout at ABV coloured ale is complimented by a sharp dry 4.5%. aftertaste. Brewed for Halloween it’s wicked! This is a recipe Then for the first time in nearly 12 months tweaked we are brewing a completely new beer. This from last came about after Frazer Snowdon who year’s recipe regularly samples our beers at The Nags (and the Head suggested brewing a beer for the local eagle-eyed branch of the Royal British Legion in aid of will notice a the poppy appeal and we were more than tweak to the happy to oblige. pumpclip too). -

Langford Beer Gin & Cider Festival

IN & CI Welcome to the 19th R, G DER E FE BE S T D I R V A O LANGFORDLANGFORD BEERBEER L F G N A L 18 GINGIN && CIDERCIDER 0 2 14 ER FESTIVALFESTIVAL - 15 SEPTEMB Welcome Live Acts - Friday Welcome to the 19th edition of our wonderful Beer, Gin and Cider Festival. As • The Underdogs - Set 1 always we have a superb range of beers, spanning the taste and colour spectrum. • Meet the brewer - Not only do we have brews from local Wiltshire, Dorset and Somerset brewers Declan from Yeovil Ales but also further afield such as Manchester, Essex and Cornwall. Holly & Ryan have • The Underdogs - Set 2 again curated a cider line up capable of quenching any thirst, and following the successful introduction of last year’s Gin Bar, head over and see Gary & Phil for a Live Acts - Saturday botanical taste infusion! • Afternoon - Open Mic Session It is with great sadness that this is the first festival without our inspirational • Parachute Drop chairman, Steve Wyre, who very sadly passed away earlier this year. Please raise a glass, whilst you’re enjoying whatever there is in it, to Steve. Cheers Steve! • Evening - Reloaded Entry, Glasses & Tokens What’s it all for? Please collect a free 2018 edition glass on entry. This acts as your receipt for your All profits from the Festival entry and beer, gin and cider will only be served to you in a 2018 glass. For Gin, you go towards a fund to build will be able to exchange your tankard for a more suitable tumbler at the Gin Bar.