Understanding the Implications of Social Media Invisible Responses for Well-Being and Relational Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Impact of Facebook on Teenagers

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 Impact Factor (2018): 7.426 A Study on Impact of Facebook on Teenagers S. T. Saravana Kumar1, S. B. Jenanee2 1Assistant Professor, Department of Commerce, Sri Krishna Adithya College of Arts & Science, Kovaipudur, Coimbatore – 42, India 2III B.Com (AF), Department of Commerce, Sri Krishna Adithya College of Arts & Science, Kovaipudur, Coimbatore – 42, India 1. Introduction still lack of strong empirical evidence to show how the use of these tools brings impact in teenager’s life. In the early 2000’s, the Web became much more personal as social networking websites were introduced and embraced 1.4 Methodology of the Study by the masses. Social networking sites (SNS) are defined as web-based services that allow individuals to construct a The methodology of this study includes the description and public or semi-public profile within a limited system, discussion of research design, sample size, sampling articulate a list of other users with whom they share a technique, tools and procedures of data collection and connection, and view and traverse their list of connections methods of analysis. The validity and value of a research and those made by others within the system. The nature and depends on the systematic method of collecting the data and terms of these connections may vary from site to site analyzing them insightfully and methodologically. In the present study, extensive and systematic use of primary data Here are some prominent examples of social media- along with the secondary data has been made. Facebook is a popular free social networking website that allows registered users to create profiles, upload photos Sources of Data and video, send messages and keep in touch with friends, Primary data family and colleagues. -

Naadac Social Media and Ethical Dilemnas for Behavioral Health Clinicians January 29, 2020

NAADAC SOCIAL MEDIA AND ETHICAL DILEMNAS FOR BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CLINICIANS JANUARY 29, 2020 TRANSCRIPT PROVIDED BY: CAPTIONACCESS LLC [email protected] www.captionaccess.com * * * * * This is being provided in a rough-draft format. Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) is provided in order to facilitate communication accessibility and may not be a totally verbatim record of the proceedings * * * * * >> SPEAKER: The broadcast is now starting. All attendee are in listen-only mode. >> Hello, everyone, and welcome to today's webinar on social media and ethical dilemma s for behavioral health clinicians presented by Michael G Bricker. It is great that you can join us today. My name is Samson Teklemariam and I'm the director of training and professional development for NAADAC, the association for addiction professionals. I'll be the organizer for this training experience. And in an effort to continue the clinical professional and business development for the addiction professional, NAADAC is very fortunate to welcome webinar sponsors. As our field continues to grow and our responsibilities evolve, it is important to remain informed of best practices and resources supporting the addiction profession. So this webinar is sponsored by Brighter Vision, the worldwide leader in website design for therapists, counselors, and addiction professionals. Stay tuned for introductions on how to access the CE quiz towards the end of the webinar immediately following a word from our sponsor. The permanent homepage for NAADAC webinars is www NAADAC.org slash webinars. Make sure to bookmark this webpage so you can stay up to date on the latest in education. Closed captioning is provided by Caption Access. -

The Early Bird Catches the News: Nine Things You Should Know About Micro-Blogging

Business Horizons (2011) 54, 105—113 www.elsevier.com/locate/bushor The early bird catches the news: Nine things you should know about micro-blogging Andreas M. Kaplan *, Michael Haenlein ESCP Europe, Avenue de la Re´publique, F-75011 Paris, France KEYWORDS Abstract Micro-blogs (e.g., Twitter, Jaiku, Plurk, Tumblr) are starting to become an Web 2.0; established category within the general group of social media. Yet, while they rapidly User-generated gain interest among consumers and companies alike, there is no evidence to explain content; why anybody should be interested in an application that is limited to the exchange of Social media; short, 140-character text messages. To this end, our article intends to provide some Micro-blogging; insight. First, we demonstrate that the success of micro-blogs is due to the specific set Twitter; of characteristics they possess: the creation of ambient awareness; a unique form of Ambient awareness push-push-pull communication; and the ability to serve as a platform for virtual exhibitionism and voyeurism. We then discuss how applications such as Twitter can generate value for companies along all three stages of the marketing process: pre- purchase (i.e., marketing research); purchase (i.e., marketing communications); and post-purchase (i.e., customer services). Finally, we present a set of rules–—TheThree Rs of Micro-Blogging: Relevance; Respect; Return–—which companies should consider when relying on this type of application. # 2010 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. All rights reserved. 1. The hare and the hedgehog: When requests from a computer virus or spyware applica- Twitter’s ‘already here’ tion. -

Drinkerdrinker

FREE DRINKERDRINKER Volume 41 No. 3 June/July 2019 The Anglers, Teddington – see page 38 WETHERSPOON OUR PARTNERSHIP WITH CAMRA All CAMRA members receive £20 worth of 50p vouchers towards the price of one pint of real ale or real cider; visit the camra website for further details: camra.org.uk Check out our international craft brewers’ showcase ales, featuring some of the best brewers from around the world, available in pubs each month. Wetherspoon also supports local brewers, over 450 of which are set up to deliver to their local pubs. We run regular guest ale lists and have over 200 beers available for pubs to order throughout the year; ask at the bar for your favourite. CAMRA ALSO FEATURES 243 WETHERSPOON PUBS IN ITS GOOD BEER GUIDE Editorial London Drinker is published on behalf of the how CAMRA’s national and local Greater London branches of CAMRA, the campaigning can work well together. Of Campaign for Real Ale, and is edited by Tony course we must continue to campaign Hedger. It is printed by Cliffe Enterprise, Eastbourne, BN22 8TR. for pubs but that doesn’t mean that we DRINKERDRINKER can’t have fun while we do it. If at the CAMRA is a not-for-profit company limited by guarantee and registered in England; same time we can raise CAMRA’s profile company no. 1270286. Registered office: as a positive, forward-thinking and fun 230 Hatfield Road, St. Albans, organisation to join, then so much the Hertfordshire AL1 4LW. better. Material for publication, Welcome to a including press The campaign will be officially releases, should preferably be sent by ‘Summer of Pub’ e-mail to [email protected]. -

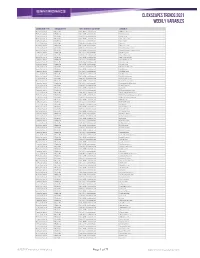

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

OPP-Iot an Ontology-Based Privacy Preservation Ap- Proach for the Internet of Things

THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE la Communauté UNIVERSITÉ GRENOBLE ALPES Spécialité : Informatique Arrêté ministériel : 27 Janvier 2017 Présentée par Thiago Moreira da Costa Thèse dirigée par Hervé Martin et codirigée par Nazim Agoulmine préparée au sein LIG - Laboratoire d’Informatique de Grenoble et de l’EDMSTII - l’Ecole Doctorale Mathématiques, Sciences et Tech- nologies de l’Information, Informatique OPP-IoT An ontology-based privacy preservation ap- proach for the Internet of Things Thèse soutenue publiquement le 27 Janvier 2017, devant le jury composé de : M, Didier DONZES Docteur, Pr. à l’Université Grenoble Alpes, Président MME, Karine ZEITOUNI Docteur, Pr. à l’Université de Versailles-Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, Rapporteur MME, Maryline LAURENT Docteur, Pr. à l’Université Telecom SudParis, Rapporteur M, Reinaldo BRAGA Docteur, Pr. à l’Institut Fédéral du Ceará, Examinateur Thiago Moreira da Costa: OPP-IoT, An ontology-based privacy preservation approach for the Internet of Things, © 27 Janvier 2017 To my beloved parents... ABSTRACT The spread of pervasive computing through the Internet of Things (IoT) represents a challenge for privacy preservation. Privacy threats are directly related to the capacity of the IoT sensing to track indi- viduals in almost every situation of their lives. Allied to that, data mining techniques have evolved and been used to extract a myriad of personal information from sensor data stream. This trust model relies on the trustworthiness of the data consumer who should infer only intended information. However, this model exposes personal in- formation to privacy adversary. In order to provide a privacy preser- vation for the IoT, we propose a privacy-aware virtual sensor model that enforces privacy policy in the IoT sensing. -

Aristotelian Rhetoric and Facebook Success in Israel's 2013 Election Campaign

Online Information Review Aristotelian rhetoric and Facebook success in Israel's 2013 election campaign: Tal Samuel-Azran Moran Yarchi Gadi Wolfsfeld Article information: To cite this document: Tal Samuel-Azran Moran Yarchi Gadi Wolfsfeld , (2015),"Aristotelian rhetoric and Facebook success in Israel's 2013 election campaign", Online Information Review, Vol. 39 Iss 2 pp. - Permanent link to this document: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/OIR-11-2014-0279 Downloaded on: 30 March 2015, At: 00:49 (PT) References: this document contains references to 0 other documents. To copy this document: [email protected] The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 18 times since 2015* Users who downloaded this article also downloaded: G E Gorman, (2015),"What’s Missing in the Digital World? Access, Digital Literacy and Digital Citizenship", Online Information Review, Vol. 39 Iss 2 pp. - Noelia Sanchez-Casado, Juan Gabriel Cegarra-Navarro, Eva Tomaseti-Solano, (2015),"Linking social networks to Utilitarian benefits through counter-knowledge", Online Information Review, Vol. 39 Iss 2 pp. - Azi Lev-On, (2015),"Uses and gratifications of members of communities of practice", Online Information Review, Vol. 39 Iss 2 pp. - Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by 172715 [] For Authors If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. -

Systematic Scoping Review on Social Media Monitoring Methods and Interventions Relating to Vaccine Hesitancy

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy www.ecdc.europa.eu ECDC TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy This report was commissioned by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and coordinated by Kate Olsson with the support of Judit Takács. The scoping review was performed by researchers from the Vaccine Confidence Project, at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (contract number ECD8894). Authors: Emilie Karafillakis, Clarissa Simas, Sam Martin, Sara Dada, Heidi Larson. Acknowledgements ECDC would like to acknowledge contributions to the project from the expert reviewers: Dan Arthus, University College London; Maged N Kamel Boulos, University of the Highlands and Islands, Sandra Alexiu, GP Association Bucharest and Franklin Apfel and Sabrina Cecconi, World Health Communication Associates. ECDC would also like to acknowledge ECDC colleagues who reviewed and contributed to the document: John Kinsman, Andrea Würz and Marybelle Stryk. Suggested citation: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020. Stockholm, February 2020 ISBN 978-92-9498-452-4 doi: 10.2900/260624 Catalogue number TQ-04-20-076-EN-N © European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the -

A Study of the Relationship Between Facebook Uses, Gratifications, And

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2017 Facebook: Help or hindrance? A study of the relationship between Facebook uses, gratifications, and depression symptoms in the older adult population Katherine Michelle Anthony Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gerontology Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Anthony, Katherine Michelle, "Facebook: Help or hindrance? A study of the relationship between Facebook uses, gratifications, and depression symptoms in the older adult population" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 15249. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/15249 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Facebook: Help or hindrance? A study of the relationship between Facebook uses, gratifications, and depression symptoms in the older adult population by Katherine Anthony A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Program of Study Committee: Raluca Cozma, Major Professor Tracy Lucht Jennifer Margrett Iowa -

Brave New World of Digital Intimacy

Brave New World of Digital Intimacy Peter Cho By CLIVE THOMPSON Published: September 5, 2008 New York Times On Sept. 5, 2006, Mark Zuckerberg changed the way that Facebook worked, and in the process he inspired a revolt. Multimedia Zuckerberg, a doe-eyed 24-year-old C.E.O., founded Facebook in his dorm room at Harvard two years earlier, and the site quickly amassed nine million users. By 2006, students were posting heaps of personal details onto their Facebook pages, including lists of their favorite TV shows, whether they were dating (and whom), what music they had in rotation and the various ad hoc “groups” they had joined (like “Sex and the City” Lovers). All day long, they’d post “status” notes explaining their moods — “hating Monday,” “skipping class b/c i’m hung over.” After each party, they’d stagger home to the dorm and upload pictures of the soused revelry, and spend the morning after commenting on how wasted everybody looked. Facebook became the de facto public commons — the way students found out what everyone around them was like and what he or she was doing. But Zuckerberg knew Facebook had one major problem: It required a lot of active surfing on the part of its users. Sure, every day your Facebook friends would update their profiles with some new tidbits; it might even be something particularly juicy, like changing their relationship status to “single” when they got dumped. But unless you visited each friend’s page every day, it might be days or weeks before you noticed the news, or you might miss it entirely. -

Breaking Trust: Shades of Crisis Across an Insecure Software Supply Chain #Accyber

Breaking Trust: Shades of Crisis Across an Insecure Software Supply Chain #ACcyber CYBER STATECRAFT INITIATIVE BREAKING TRUST: Shades of Crisis Across an Insecure Software Supply Chain Trey Herr, June Lee, William Loomis, and Stewart Scott Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. Cyber Statecraft Initiative The Cyber Statecraft Initiative works at the nexus of geopolitics and cybersecurity to craft strategies to help shape the conduct of statecraft and to better inform and secure users of technology. This work extends through the competition of state and non-state actors, the security of the internet and computing systems, the safety of operational technology and physical systems, and the communities of cyberspace. The Initiative convenes a diverse network of passionate and knowledgeable contributors, bridging the gap among technical, policy, and user communities. CYBER STATECRAFT INITIATIVE BREAKING TRUST: Shades of Crisis Across an Insecure Software Supply Chain Trey Herr, June Lee, William Loomis, and Stewart Scott ISBN-13: 978-1-61977-112-3 Cover illustration: Getty Images/DavidGoh This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The author is solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. -

The Complete Guide to Social Media from the Social Media Guys

The Complete Guide to Social Media From The Social Media Guys PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 08 Nov 2010 19:01:07 UTC Contents Articles Social media 1 Social web 6 Social media measurement 8 Social media marketing 9 Social media optimization 11 Social network service 12 Digg 24 Facebook 33 LinkedIn 48 MySpace 52 Newsvine 70 Reddit 74 StumbleUpon 80 Twitter 84 YouTube 98 XING 112 References Article Sources and Contributors 115 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 123 Article Licenses License 125 Social media 1 Social media Social media are media for social interaction, using highly accessible and scalable publishing techniques. Social media uses web-based technologies to turn communication into interactive dialogues. Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein define social media as "a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, which allows the creation and exchange of user-generated content."[1] Businesses also refer to social media as consumer-generated media (CGM). Social media utilization is believed to be a driving force in defining the current time period as the Attention Age. A common thread running through all definitions of social media is a blending of technology and social interaction for the co-creation of value. Distinction from industrial media People gain information, education, news, etc., by electronic media and print media. Social media are distinct from industrial or traditional media, such as newspapers, television, and film. They are relatively inexpensive and accessible to enable anyone (even private individuals) to publish or access information, compared to industrial media, which generally require significant resources to publish information.