Hari OM CMW NEWS 151 JAN 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divine Discourses His Holiness Shri. Datta Swami

DIVINE DISCOURSES Volume 19 HIS HOLINESS SHRI. DATTA SWAMI Shri Datta Swami Sri Datta Jnana Prachara Parishat Copyright: © 2007 Sri Datta Jnana Prachara Parishat, Vijayawada, India. All rights reserved. Shri Datta Swami Sri Datta Jnana Prachara Parishat CONTENTS 1. SOME PEOPLE CRITICIZE EVERYONE WITHOUT ESTABLISHING ANYTHING FROM THEIR SIDE 1 Meaning of Shrauta and Smaarta 1 Religion- Specific God & Mode of Worship 7 Conservative-negative Approach Belongs to Ignorant Followers of Any Religion 8 No Point Registered As Property of Any Human Being 20 There is Tradition in Hinduism To Stress On Any Point As Absolute23 2. IF PURE NIVRUTTI-BOND EXISTS ONLY GOD’S WORK SEEN AS EXTERNAL VISIBLE PROOF OF INTERNAL INVISIBLE LOVE TO GOD 31 Develop Devotion to God So That Worldly Bonds Become Weak & Disappear Gradually As Natural Consequence 31 No Social Service Pure & Effective Without Spiritual Background 34 3. DEVOTION MEANS SACRIFICE OF ONE’S OWN MONEY & NOT GOVERNMENT’S MONEY SECRETLY 37 Ruler Should Care Comments of Every Citizen in His Kingdom 37 Money of King Not Be Spent for Any Purpose Including Divine Service Without Permission 38 Response of Rama Through His Practical Actions 40 4. ONLY HOUSE HOLDER HAS BOTH OPTIONS TO SACRIFICE WORK AND WEALTH 42 Repeated Practice Means Blind Traditional Practice 42 5. SARASWATI RIVER OF SPIRITUAL KNOWLEDGE 45 Burning Self In Fire Of Knowledge Is Penance 45 6. SARASWATI RIVER OF SPIRITUAL KNOWLEDGE 51 Phases – Properties – Time – Angle of Reference 51 Entry of Unimaginable God in Human Form Never Direct 53 7. SARASWATI RIVER OF SPIRITUAL KNOWLEDGE 57 Top Most Scholars Even Neglect Miracles Giving Top Most Importance To Spiritual Knowledge Only 57 Knowledge Can’t Be Received By Hard Minds Due to Intense Ignorance 59 8. -

IN the HIGH COURT of JHARKHAND at RANCHI. W.P. (PIL) No. 3694 of 2015 COURT on ITS OWN MOTION

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JHARKHAND AT RANCHI. W.P. (PIL) No. 3694 of 2015 COURT ON ITS OWN MOTION Dated: 10th August, 2015 Per Virender Singh, C.J. This court noticed through electronic media of today i.e. 10.08.2015 that stampede took place on 10.08.2015 at about 04:30 a.m., near a temple of Goddess Durga in Belbagan locality which is about 3 k.m far from Baba Baidya Nath Dham Temple, Deoghar. The said fact is also available on e- newspaper, prabhatkhabar.com. 2. According to the report, the tragedy took place when people started trying to jump queue in order to get closer to the temple. In the aforesaid incident about 11 persons have been reported dead and more than 50 persons were injured. 3. Suo Motu cognizance is being taken on the aforesaid news item and following persons are being made as party respondents:- (i). The State of Jharkhand through the Chief Secretary, Jharkhand; (ii). The Dy. Commissioner, Deoghar; (iii). The Director General of Police, Jharkhand; (iv) The Superintendent of Police, Deoghar; (v). The Jharkhand State Hindu Religious Trust Board, Jharkhand; and (vi). The Management Board, Baidyanath Dham Temple, Deoghar. 4. On asking of the Court, Mr. Ajit Kumar, learned Additional Advocate General, appears and accepts notice on behalf of the State. 5. Let notice be issued to the remaining respondents. 6. The respondents are being directed to file their counter affidavits with regard to acknowledge this court about the cause of accident, measures, both interim and final, are being taken for preventing the similar accident in future, about the persons who are responsible for the above accident and the steps which has been taken against them. -

View Entire Book

ORISSA REVIEW VOL. LXI NO. 12 JULY 2005 DIGAMBAR MOHANTY, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary BAISHNAB PRASAD MOHANTY Director-cum-Joint Secretary SASANKA SEKHAR PANDA Joint Director-cum-Deputy Secretary Editor BIBEKANANDA BISWAL Associate Editor Sadhana Mishra Editorial Assistance Manas R. Nayak Cover Design & Illustration Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Manoj Kumar Patro D.T.P. & Design The Orissa Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Orissa’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Orissa Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Orissa. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Orissa, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Orissa Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. E-mail : [email protected] Five Rupees / Copy Visit : www.orissagov.nic.in Fifty Rupees / Yearly Contact : Ph. 0674-2411839 CONTENTS Editorial Landlord Sri Jagannath Mahaprabhu Bije Puri Dr. Chitrasen Pasayat ... 1 Jamesvara Temple at Puri Ratnakar Mohapatra ... 6 Vedic Background of Jagannath Cult Dr. Bidyut Lata Ray ... 15 Orissan Vaisnavism Under Jagannath Cult Dr. Braja Kishore Swain ... 18 Bhakta Kabi Sri Bhakta Charan Das and His Work Somanath Jena ... 23 'Manobodha Chautisa' The Essence of Patriotism in Temple Multiplication - Dr. Braja Kishore Padhi ... 26 Kulada Jagannath Rani Suryamani Patamahadei : An Extraordinary Lady in Puri Temple Administration Prof. Jagannath Mohanty ... 30 Sri Ratnabhandar of Srimandir Dr. Janmejaya Choudhury ... 32 Lord Jagannath of Jaguleipatna Braja Paikray ... 34 Jainism and Buddhism in Jagannath Culture Pabitra Mohan Barik ... 36 Balabhadra Upasana and Tulasi Kshetra Er. -

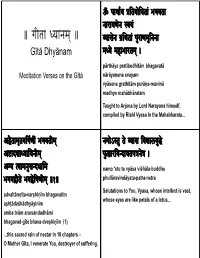

Microsoft Powerpoint

ॐ पाथाय ितबाधताे भगवता नारायणने वय ꠱ गीतॎ यॎनम् ꠱ यासेन थता पराणमिननापराणमु ुिनना Gītā Dhyānam मये महाभारतम् ꠰ pārthāya pratibodhitām bhagavatā Meditation Verses on the Gītā nārāyaṇena svayam vyāsena grathitām purāṇa-muninā madhyemahābhāratam Taught to Arjuna by Lord Narayana himself, compiled by Rishi Vyasa in the Mahabharata... अैतामतवषृ णी भगवतीम् नमाऽते त े यास वशालबु े अादशायाीयनीम् फु ारवदायतपन꠰ेे अब वामनसदधामवामनसदधामु namo 'stu te vyāsa viśhāla-buddhe phullāravindāyata-patra-netra भगवत े भवभवषणीमेषणीम् ꠱१꠱ Salutations to You, Vyyasa, whose intellect is vast, advaitāmṛita-varṣhiṇīm bhagavatīm whose eyes are like petals of a lotus... aṣhṭādaśhādhyāyinīm amba tvām anusandadhāmi bhagavad-gīte bhava-dveṣhiṇīm (1) ...this sacred rain of nectar in 18 chapters – O Mother Gita, I venerate You, destroyer of suffering. येन वया भारततलपै ूण पपारजाताय तावे े कपाणयै े꠰ वालता ेे ानमय दप ꠱२꠱ ानमु य कृ णाय गीतामृतदहु ेे नम ꠱३꠱ yena tvayā bhārata-taila-pūrṇaḥ prapanna-pārijātāya prajvālito jñāna-mayaḥ pradīpaḥ (2) totra-vetraika-pāṇaye jñāna-mudrāya kṛiṣhṇāya ...by whom the lamp filled with the oil of the gītāmṛita-dhduhenamaḥ (3) Mahabharata was lit with the flame of knowledge. Salutations to Krishna , who blesses the surrendered, in whose hands are a staff and the symbol of knowledge, who milks the Gita's nectar. सवापिनषदाे े गावा े दाधाे गापालनदने ꠰ वसदेवसत देव क सचाणरमदू नम꠰् पाथा े वस सध ीभााेे दधु गीतामृत महत् ꠰꠰ देेवकपरमानद कृ ण वदेे जगु म् ꠱꠱ sarvopaniṣhado gāvo vasudeva-sutam devam dogdhā gopāla-nandanaḥ kaḿsa-cāṇūra-mardanam pārtho vatsaḥ sudhīr bhoktā devakī-paramānandam ddhdugdham gītāmṛitam mahthat (4) kṛiṣhṇam vande jdjagad-gurum (5) The Upanishads are cows, Krishna is the cowherd, I revere Sri Krishna, teacher of all, son of Vasudeva, Arjuna is the calf, and wise people enjoy the sacred destroyer of Kamsa and Chanura, who is the delight nectar milked from the Gita. -

Tourist Places in and Around Dhanbad

Tourist Places in and around Dhanbad Dhanbad the coal capital of India lies at the western part of Eastern Indian Shield, the Dhanbad district is ornamented by several tourist spots, namely Parasnath Hill, Parasnath Temple, Topchanchi, famous Jharia coalfields, to mention a few. Other important places are Bodh Gaya, Maithon Dam, and this town is only at 260 km distance by rail route from Kolkata. Bodh Gaya Lying at 220 km distance from Dhanbad. Bodh Gaya is the place where Gautam Buddha attained unsurpassed, supreme Enlightenment. It is a place which should be visited or seen by a person of devotion and which would cause awareness and apprehension of the nature of impermanence. About 250 years after the Enlightenment, the Buddhist Emperor, Ashoka visited the site of pilgrimage and established the Mahabodhi temple. Parasnath Temple The Parasnath Temple is considered to be one of the most important and sanctified holy places of the Jains. According to Jain tradition, no less than 23 out of 24 Tirthankaras (including Parsvanatha) are believed to have attained salvation here. Baidyanath Temple Baidyanath Jyotirlinga temple, also known as Baba dham and Baidyanath dham is one of the twelve Jyotirlingas, the most sacred abodes of Shiva. It is located in Deoghar at a distance of 134 km from Dhanbad. It is a temple complex consisting of the main temple of Baba Baidyanath, where the Jyotirlinga is installed, and 21 other temples. Maithon Dam Maithon is 52 km from Dhanbad. This is the biggest reservoir in the Damodar Valley. This dam, designed for flood control, has been built on Barakar river. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 1 1st Pada 1st Adikaranam to 11th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 31 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Summary 5 Introduction of Brahma Sutra 6 1 Jijnasa adhikaranam 1 a) Sutra 1 103 1 1 2 Janmady adhikaranam 2 a) Sutra 2 132 2 2 3 Sastrayonitv adhikaranam 3 a) Sutra 3 133 3 3 4 Samanvay adhikaranam 4 a) Sutra 4 204 4 4 5 Ikshatyadyadhikaranam: (Sutras 5-11) 5 a) Sutra 5 324 5 5 b) Sutra 6 353 5 6 c) Sutra 7 357 5 7 d) Sutra 8 362 5 8 e) Sutra 9 369 5 9 f) Sutra 10 372 5 10 g) Sutra 11 376 5 11 2 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 6 Anandamayadhikaranam: (Sutras 12-19) 6 a) Sutra 12 382 6 12 b) Sutra 13 394 6 13 c) Sutra 14 397 6 14 d) Sutra 15 407 6 15 e) Sutra 16 411 6 16 f) Sutra 17 414 6 17 g) Sutra 18 416 6 18 h) Sutra 19 425 6 19 7 Antaradhikaranam: (Sutras 20-21) 7 a) Sutra 20 436 7 20 b) Sutra 21 448 7 21 8 Akasadhikaranam : 8 a) Sutra 22 460 8 22 9 Pranadhikaranam : 9 a) Sutra 23 472 9 23 3 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 10 Jyotischaranadhikaranam : (Sutras 24-27) 10 a) Sutra 24 486 10 24 b) Sutra 25 508 10 25 c) Sutra 26 513 10 26 d) Sutra 27 517 10 27 11 Pratardanadhikaranam: (Sutras 28-31) 11 a) Sutra 28 526 11 28 b) Sutra 29 538 11 29 c) Sutra 30 546 11 30 d) Sutra 31 558 11 31 4 SUMMARY Brahma Sutra Bhasyam Topics - 191 Chapter – 1 Chapter – 2 Chapter – 3 Chapter – 4 Samanvaya – Avirodha – non – Sadhana – spiritual reconciliation through Phala – result contradiction practice proper interpretation Topics - 39 Topics - 47 Topics - 67 Topics 38 Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics 1 11 1 13 1 06 1 14 2 07 2 08 2 08 2 11 3 13 3 17 3 36 3 06 4 08 4 09 4 17 4 07 5 Lecture – 01 Puja: • Gratitude to lord for completion of Upanishad course (last Chandogya Upanishad + Brihadaranyaka Upanishad). -

Bhagavad Gita Chapters 13-18 Knowledge

The Bhagavad Gita in Summary 1 Discover the wisdom of this powerful ancient Indian classic The Bhagavad Gita a series of three meetings on its 18 Chapters The Third Meeting on Chapters 13-18 Review of Chapters 1 to 12, on Action & Devotion ........................................................................................ 2 Summary of Chapters 13 to 18 Knowledge, Jnana Yoga ............................................................................... 3 The "Lord's Song": a Personal Book and Guide ........................................................................................... 8 The Song ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 The Dhyana Sloka ......................................................................................................................................... 10 The Bhagavad Gita in Summary 2 Review of Chapters 1 to 12, on Action & Devotion H. P. Blavatsky says that the Bhagavad Gita, “The Lord’s Song,” is a dialogue between Krishna, the “Charioteer,” and Arjuna, his Chela, on the highest spiritual philosophy. The Theosophical approach to the Gita is that “When Krishna uses the personal pronoun throughout the Gita [“I,” “Me” etc.] he is not referring to his own personality, but to the Self of All.” (Notes on the Bhagavad Gita, 157) This is important as it places our attention inside, instead of outside to an apparent Deity, and encourages us in self-reliance. In the first two meetings we saw the structure of the 18 Chapters of the Gita divided into the three divisions of natural progress. Some of these we saw were: Action, Devotion leading to Knowledge. these correlate to Ignorance, Learning and Mastery. Theosophical teachings are able take us out of Ignorance, show how to navigate the temptations of Learning and are a guide towards self Mastery. The aim is union with the Divine, its means are twofold. One is positive (to recognise the inner deity), the other is negative (to renounce selfish interests). -

Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C

“Srimad-Bhagavatam – Canto Ten” by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Summary: Srimad-Bhagavatam is compared to the ripened fruit of Vedic knowledge. Also known as the Bhagavata Purana, this multi-volume work elaborates on the pastimes of Lord Krishna and His devotees, and includes detailed descriptions of, among other phenomena, the process of creation and annihilation of the universe. His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada considered the translation of the Bhagavatam his life’s work. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This is an evaluation copy of the printed version of this book, and is NOT FOR RESALE. This evaluation copy is intended for personal non- commercial use only, under the “fair use” guidelines established by international copyright laws. You may use this electronic file to evaluate the printed version of this book, for your own private use, or for short excerpts used in academic works, research, student papers, presentations, and the like. You can distribute this evaluation copy to others over the Internet, so long as you keep this copyright information intact. You may not reproduce more than ten percent (10%) of this book in any media without the express written permission from the copyright holders. Reference any excerpts in the following way: “Excerpted from “Srimad-Bhagavatam” by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, courtesy of the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, www.Krishna.com.” This book and electronic file is Copyright 1977-2003 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, 3764 Watseka Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90034, USA. All rights reserved. For any questions, comments, correspondence, or to evaluate dozens of other books in this collection, visit the website of the publishers, www.Krishna.com. -

Panchadashee – 05 Mahavakya Vivekah

Swami Vidyaranya’s PANCHADASHEE – 05 MAHAVAKYA VIVEKAH Fixing the Meaning of the Great Sayings MODERN-DAY REFLECTIONS On a 13TH CENTURY VEDANTA CLASSIC by a South African Student TEXT Swami Gurubhaktananda 47.05 2018 A FOUNDATIONAL TEXT ON VEDANTA PHILOSOPHY PANCHADASHEE – An Anthology of 15 Texts by Swami Vidyaranyaji PART Chap TITLE OF TEXT ENGLISH TITLE No. No. Vers. 1 Tattwa Viveka Differentiation of the Supreme Reality 65 2 Maha Bhoota Viveka Differentiation of the Five Great Elements 109 3 Pancha Kosha Viveka Differentiation of the Five Sheaths 43 SAT: 4 Dvaita Viveka Differentiation of Duality in Creation 69 VIVEKA 5 Mahavakya Viveka Fixing the Meaning of the Great Sayings 8 Sub-Total A 294 6 Chitra Deepa The Picture Lamp 290 7 Tripti Deepa The Lamp of Perfect Satisfaction 298 8 Kootastha Deepa The Unchanging Lamp 76 CHIT: DEEPA 9 Dhyana Deepa The Lamp of Meditation 158 10 Nataka Deepa The Theatre Lamp 26 Sub-Total B 848 11 Yogananda The Bliss of Yoga 134 12 Atmananda The Bliss of the Self 90 13 Advaitananda The Bliss of Non-Duality 105 14 Vidyananda The Bliss of Knowledge 65 ANANDA: 15 Vishayananda The Bliss of Objects 35 Sub-Total C 429 WHOLE BOOK 1571 AN ACKNOWLEDGEMENT BY THE STUDENT/AUTHOR The Author wishes to acknowledge the “Home Study Course” offerred by the Chinmaya International Foundation (CIF) to students of Vedanta in any part of the world via an online Webinar service. These “Reflections” are based on material he has studied under this Course. CIF is an institute for Samskrit and Indology research, established in 1990 by Pujya Gurudev, Sri Swami Chinmayananda, with a vision of it being “a bridge between the past and the present, East and West, science and spirituality, and pundit and public.” CIF is located at the maternal home and hallowed birthplace of Adi Shankara, the great saint, philosopher and indefatigable champion of Advaita Vedanta, at Veliyanad, 35km north-east of Ernakulam, Kerala, India. -

The Lord and His Land

Orissa Review * June - 2006 The Lord and His Land Dr. Nishakar Panda He is the Lord of Lords. He is Jagannath. He century. In Rajabhoga section of Madala Panji, is Omniscient, Omnipotent and Omnipresent. Lord Jagannatha has been described as "the He is the only cult, he is the only religion, he king of the kingdom of Orissa", "the master is the sole sect. All sects, all 'isms', all beliefs or the lord of the land of Orissa" and "the god and all religions have mingled in his eternal of Orissa". Various other scriptures and oblivion. He is Lord Jagannatha. And for narrative poems composed by renowned poets Orissa and teeming millions of Oriyas are replete with such descriptions where He is the nerve centre. The Jagannatha has been described as the institution of Jaganatha sole king of Orissa. influences every aspect of the life in Orissa. All spheres of Basically a Hindu our activities, political, deity, Lord Jagannatha had social, cultural, religious and symbolized the empire of economic are inextricably Orissa, a collection of blended with Lord heterogeneous forces and Jagannatha. factors, the individual or the dynasty of the monarch being A Political Prodigy : the binding force. Thus Lord Lord Jaganatha is always Jagannatha had become the and for all practical proposes national deity (Rastra Devata) deemed to be the supreme besides being a strong and monarch of the universe and the vivacious force for integrating Kings of Orissa are regarded as His the Orissan empire. But when the representatives. In yesteryears when Orissa empire collapsed, Lord Jagannatha had been was sovereign, the kings of the sovereign state seen symbolizing a seemingly secular force of had to seek the favour of Lord Jaganatha for the Oriya nationalism. -

View Entire Book

Orissa Review * June - 2006 A Cult to Salvage Mankind Sarat Chandra The cosmic and terrestrial : both realities are The Hindu inclusiveness is nowhere as reflected in the Jagannath cult of Orissa. The evident as in the rituals of Lord Jagannath. Even cosmic reality of the undying spirit which romance is not excluded in the deity's schedule: abides, endures and sustains; the cosmic reality Once in a week the God is closeted with his of birth and death, as well as the beauty and consort Laksmi (in the ritual Ekanta). The refinement of the terrestrial world are mirrored Sayana Devata golden sculpture used in the in this all-inclusive mid-night ritual after the religious practice. "The Bada Singhara Dhupa, is visible and invisible both not only suggestive but worlds meet in man", even explicit. sang the British poet T.S.Eliot in the Four Over a year Lord Quartets. We may say Jagannath, like human that the Jagannath cult is beings, is engaged in designed to reflect both multification activities. the visible, this-worldly On one occasion realities as well as the (Banabhoji Besha) He cosmic phenomena. sets out on a picnic trip, Hence, the cult reflects a to an idyllic forest land, life style of a god who has which is suggestive of the numerous human God's love for natural attributes. beauty. On the other occasions (seven times in a year), the Lord goes This makes the God and the cult unique. for hunting expeditions. During the summer Several traits characterize the God: the everyday rituals of bathing, brushing of teeth, he goes for boat rides for twenty-one days dressing-up and partaking of food materials. -

Special Survey Reports on Selected Towns Madhupur

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 BIHAR SERIES 4 PARTVI·B SPECIAL SURVEY REPORTS ON SELECTED TOWNS MADHUPUR Field investigation and first draft RAJENDRA PRASAD Tabulation Officer Supervision, guidance and final draft SHAHBUDDIN MOHAMMAD Deputy Director Editor J. C. KALRA Deputy Director ofCrmSfls Operations, Bihar 1971 CENSUS PUBUCATIONS, BIHAR (All the Census PublicatioDs of this State will bear Sed PART I-A General Report (Report on. data yielded from F and Tables on Mother-tongue and Religion) PART I-B General Report (Detailed analysis of the Demogm Social, Cultural and Migration Pattern) PART I-C Subsidiary Tables PART II-A· • General Population Tables (A-I, A-II, A-III and , and P.C.A.)'" PART II-A General Population Tables (Standard Urban Area SuPPLEMENT PORTRAIT OF POPULATION'" PART n-B(i) General Economic Tables (B-1 Part A and B-II)" P-ART H-B(ii)· General Economic Tables (B-1 Part B, B-UI, B-IV , B-VII to B-IX)t PART II-B(iii) General Economic Tables (B-V and B-VI)t PART II-C(i) Social and Cultural Tables (C-VII and C-VIII)" PART 1I-f:(ii) Social and Cultural Tables (C-l to C-VI and Fertility Tabl PART II·D Migration Tab1est P'ART III-A Report on Establishments and Subsidiary Tables Establishment Tablest PARTIII-B Establkhment Tables .. PART IV Housing Report and Tables* pARTV-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tril: PARTVl-A Town-Directory" PARTVl-B Special Survey Reports on selected townst PARTVI-C Survey Reports on selected villages I PART VIIl-A Administratiol\ Report on Enumeration * Jr For official :PART VIII-B Administration