Philosophy of Sri Madhvacarya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir

Abhinavagupta's Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:39987948 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Abhinavagupta’s Portrait of a Guru: Revelation and Religious Authority in Kashmir A dissertation presented by Benjamin Luke Williams to The Department of South Asian Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of South Asian Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2017 © 2017 Benjamin Luke Williams All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Parimal G. Patil Benjamin Luke Williams ABHINAVAGUPTA’S PORTRAIT OF GURU: REVELATION AND RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY IN KASHMIR ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to recover a model of religious authority that placed great importance upon individual gurus who were seen to be indispensable to the process of revelation. This person-centered style of religious authority is implicit in the teachings and identity of the scriptural sources of the Kulam!rga, a complex of traditions that developed out of more esoteric branches of tantric "aivism. For convenience sake, we name this model of religious authority a “Kaula idiom.” The Kaula idiom is contrasted with a highly influential notion of revelation as eternal and authorless, advanced by orthodox interpreters of the Veda, and other Indian traditions that invested the words of sages and seers with great authority. -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

Sripadaraja Mutt Address

Sripadaraja Mutt Address Head Office : Sri Sripadaraja Mutt (Mulbagal Mutt) Sri Narasimha Theertha, Mulbagal - 563 131, Karnataka, India Contact:- Sri. H B Jayaraj Ph: (08159) 290839, 9242613866 (Resi) (08159) 542686 Mulbagilu Branch - Mulbagal Town Mutt Sri Sripadaraja Pratistitha Sri Lakshminarayana and Sri Vysaraja Pratistitha 1st Hanuman Statue Mulbagal - 563131 Contact:- Sri. H B Jayaraj Ph: (08159) 290839, 9242613866 Nangli branch Sri Srikantha Theertha Brindavana, Nangli Village Mulbagal Taluk Contact:- Sri. H B Jayaraj Ph: (08159) 290839, 9242613866 Bangalore Branch 58, Raghavendra Colony, Chamrajpet Bangalore - 560 018 Contact:- Sri. S R Sreedharachar Ph:(080)266730232 Bangalore-Rajaji Nagar Branch # 542/31, 63rd Cross, Rajajainagar Near Bhasyam Circle Bangalore Contact:- Sri. Ravikiran Ph: 9880054620 Jigani Branch Sri Raghavendra Swamy Brindavan Near Busstand, Jigani Anekall Taluk Bangalore - 562 106 Contact:- Sri. Prakash & Sri Giriachar Ph: (080) 7826317 99010 975671 Mysore Branch Sri Sripadaraja Mutt (Sri Devendra Theertha Mutt) Ramanujam Road Mysore - 570 001 Source : Sripadaraja Mutt.org Collection by Narahari Sumadhwa Page 1 Sripadaraja Mutt Address Srirangapatna Branch Sri Gnananidhigala Brindavana, Water Gate, Srirangapatna - 571 438 Contact:- Sri. Jayasimhachar, & Sri Ananda Theetha Ph: (08326) 253540 (08326) 252340 Yeragambali Branch Sri Raghunatha Theerhtara Brindavana Yeragampally Yelandur Taluk Contact :- Sri. Bala Krishna achar (08221) 223924 Thayuru Branch Sri Gunanidhi Theertha Brindavan Kapila River Thayuru Contact :- Sri. Bala Krishna Achar (08221) 223924 Udupi Branch Car Street Udupi ANDRA PRADESH BRANCHES – Penugonda Branch Sri Sripadarja Prathisthitha Hanumal Temple Old Post Office Street Penukonda Contact:- Sri. Ananta Rao Ph: (08555) 221090 Sri Uddanda Ramachandra Theertha Brindavan Bangalore - Hyderabad Highway Penukonda Contact:- Sri. Ananta Rao Ph: (08555) 221090 Punganur Branch Brahmin Street Punganur Contact:- Sri. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Understanding the Super Excellence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism

Understanding the Super Excellence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism Understanding the Super Excellence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. So that is the theme, understanding the super excellence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. Srila Prabhupada ki jay! He was and he is Gaudiya Vaishnava, coming in the line of disciplic succession and we are getting connected. So we are making this presentation, I won’t say this is complete presentation but some introductory presentation to make the point that Gaudiya Vaishnavism is super excellent like, mattah parataram nanyat kincid asti dhananjaya mayi sarvam idam protam sutre mani-gana iva [Bg 7.7] Translation: O conqueror of wealth [Arjuna], there is no Truth superior to Me. Everything rests upon Me, as pearls are strung on a thread. Krishna said no one is equal to me and no one is superior to me. So Krishna is super excellent personality of godhead. So like that there are different features of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, so we have picked up a few items which are listed here. Achintya-Bheda-Abheda tattva or philosophy or the commentary on vedanta sutra is of Gaudiya Vaishnavas is super excellent, so that one. And Gaudiya sampradaya is super excellent and raganuga sadhana bhakti. And Goloka dhama, amongst all the dhamas and there are many of them, is the topmost realm, super excellent and that is Gaudiya Vaishnavas preference, they don’t settle on any other level they go all the way to the top, topmost abode, super excellent abode Goloka. Mellows of bhakti, Gaudiya Vaishnavas only settle for the topmost rasa, madhurya rasa. That is what Sri Krishna Chaitanya Mahaprabhu relished and shared. -

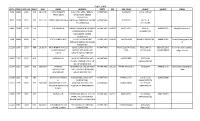

Of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN

Page 1 of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR_SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN REG_NUM QUALIF MOBILE EMAIL 7356 1994S 2091 345 28.04.49 KRISHNAMSETY D-12, IVRI, QTRS, HEBBAL, KARNATAKA VCI/85/94 B.V.Sc./APAU/ PRABHODAS BANGALORE-580024 KARNATAKA 8992 1994S 3750 425 03.01.43 SATYA NARAYAN SAHA IVRI PO HA FARM BANGALORE- KARNATAKA VCI/92/94 B.V.Sc. & 24 KARNATAKA A.H./CU/66 6466 1994S 1188 295 DINTARAN PAL ANIMAL NUTRITION DIV NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2150/91 BVSc & 9480613205 [email protected] ADUGODI HOSUR ROAD AH/BCKVV/91 BANGALORE 560030 KARNATAKA 7200 1994S 1931 337 KAJAL SANKAR ROY SCIENTIST (SS) NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2254/93 BVSc&AH/BCKVV/93 9448974024 [email protected] ADNGODI BANGLORE 560030 m KARNATAKA 12229 1995 2593 488 26.08.39 KRISHNAMURTHY.R,S/ #1645, 19TH CROSS 7TH KARNATAKA APSVC/205/94,VCI/61 BVSC/UNI OF 080 25721645 krishnamurthy.rayakot O VEERASWAMY SECTOR, 3RD MAIN HSR 7/95 MADRAS/62 09480258795 [email protected] NAIDU LAYOUT, BANGALORE-560 102. 14837 1995 5242 626 SADASHIV M. MUDLAJE FARMS BALNAD KARNATAKA KAESVC/805/ BVSC/UAS VILLAGE UJRRHADE PUTTUR BANGALORE/69 DA KA KARANATAKA 11694 1995 2049 460 29/04/69 JAMBAGI ADIGANGA EXTENSION AREA KARNATAKA 591220 KARNATAKA/2417/ BVSC&AH 9448187670 shekharjambagi@gmai RAJASHEKHAR A/P. HARUGERI BELGAUM l.com BALAKRISHNA 591220 KARANATAKA 10289 1995 624 386 BASAVARAJA REDDY HUKKERI, BELGAUM DISTT. KARNATAKA KARSUL/437/ B.V.SC./GAS 9241059098 A.I. KARANATAKA BANGALORE/73 14212 1995 4605 592 25/07/68 RAJASHEKAR D PATIL, AMALZARI PO, BILIGI TQ, KARNATAKA KARSV/2824/ B.V.SC/UAS S/O DONKANAGOUDA BIJAPUR DT. -

Samskara-By-Ur-Anantha-Murthy.Pdf

LITERATURE ~O} OXFORD"" Made into a powerful, award-winning film in 1970, this important Kannada novel of the sixties has received widespread acclaim from both critics and general read ers since its first publication in 1965. As a religious novel about a decaying brahmin colony in the south Indian village of Karnataka, Samskara serves as an allegory rich in realistic detail, a contemporary reworking of ancient Hindu themes and myths, and a serious, poetic study of a religious man living in a community of priests gone to seed. A death, which stands as the central event in the plot, brings in its wake a plague, many more deaths, live questions with only dead answers, moral chaos, and the rebirth of one man. The volume provides a useful glos sary of Hindu myths, customs, Indian names, flora, and other terms. Notes and an afterword enhance the self contained, faithful, and yet readable translation. U.R. Anantha Murthy is a well-known Indian novelist. The late A.K. Ramanujan w,as William E. Colvin Professor in the Departments of South Asian Languages and Civilizations and of Linguistics at the University of Chicago. He is the author of many books, including The Interior Landscape, The Striders, The Collected Poems, and· several other volumes of verse in English and Kannada. ISBN 978-0-19-561079-6 90000 Cover design by David Tran Oxford Paperbacks 9780195 610796 Oxford University Press u.s. $14.95 1 1 SAMSKARA A Rite for a Dead Man Sam-s-kiira. 1. Forming well or thoroughly, making perfect, perfecting; finishing, refining, refinement, accomplishment. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 4 3rd Pada 1st Adikaranam to 6th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 16 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No introduction 4024 179 Archiradyadhikaranam 179 a) Sutra 1 4026 179 518 180 Vayvadhikaranam 180 a) Sutra 2 4033 180 519 181 Tadidadhikaranam 4020 181 a) Sutra 3 4044 181 520 182 Ativahikadhikaranam 182 a) Sutra 4 4049 182 521 b) Sutra 5 4054 182 522 c) Sutra 6 4056 182 523 i S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 183 Karyadhikaranam: 183 a) Sutra 7 4068 183 524 b) Sutra 8 4070 183 525 c) Sutra 9 4073 183 526 d) Sutra 10 4083 183 527 e) Sutra 11 4088 183 528 f) Sutra 12 4094 183 529 g) Sutra 13 4097 183 530 h) Sutra 14 4099 183 531 184 Apratikalambanadhikaranam: 184 a) Sutra 15 4118 184 532 b) Sutra 16 4132 184 533 ii Lecture 368 4th Chapter : • Phala Adhyaya, Phalam of Upasaka Vidya. Mukti Phalam Saguna Vidya Nirguna Vidya - Upasana Phalam - Aikya Jnanam - Jnana Phalam • Both together is called Mukti Phalam Trivida Mukti (Threefold Liberation) Jeevan Mukti Videha Mukti Krama Mukti Mukti / Moksha Phalam Positive Language Negative Language - Ananda Brahma Prapti - Bandha Nivritti th - 4 Pada - Samsara Nivritti rd - 3 Pada - Dukha Nivritti - Freedom from Samsara, Bandha, Dukham st - 1 Pada Freedom from bonds of Karma, Sanchita ( Destroyed), Agami (Does not come) - Karma Nivritti nd - 2 Pada nd rd • 2 and 3 Padas complimentary both deal with Krama Mukti of Saguna Upasakas, Involves travel after death.4024 Krama Mukti Involves Travel 3 Parts / Portions of Krama Mukti 2nd Pada – 1st Part 2nd Part Travel 3rd Part Reaching Departure from Body for Travel Gathi Gathanya Prapti only for Krama Mukti - Not for Videha Mukti or Jeevan Mukti - Need not come out of body - Utkranti - Panchami – Tat Purusha Utkranti – 1st Part - Departure Pranas come to Hridayam Nadis Dvaras Shine Small Dip in Brahma Loka Appropriate Nadi Dvara Jiva goes • 2nd Part Travel - Gathi and Reaching of Krama Mukti left out. -

Fairs and Festivals, Part VII-B

PM. 179.9 (N) 750 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II ANDHRA PRADESII PART VII-B (9) A. CHANDRA SEKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh Price: Rs. 5.75 P. or 13 Sh. 5 d. or 2 $ 07 c. 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH (All the Census Publications of this State will bear Vol. No. II) J General Report PART I I Report on Vital Statistics (with Sub-parts) l Subsidiary Tables PART II-A General Population Tables PART II-B (i) Economic Tables [B-1 to B-IVJ PART II-B (ii) Economic Tables [B-V to B-IX] PART II-C Cultural and Migration Tables PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishme"nts (with Subsidiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Survey Monographs PART VII-A tIn Handicraft Survey Reports (Selected Crafts) PART VII-A (2) f PA&T VII-B Fairs and Festivals PART VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration } (Not for PART VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation Sale) PART IX Maps PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City PHOTO PLATE I Tower at the entrance of Kodandaramaswamy temple, Vontimitta. Sidhout Tdluk -Courtesy.- Commissioner for H. R. & C. E. (Admn. ) Dept., A. p .• Hydcrabad. F 0 R,E W 0 R D Although since the beginning of history, foreign traveller~ and historians have recorded the principal marts and ~ntrepot1'l of commerce in India and have even mentioned important festival::» and fairs and articles of special excellence availa ble in them, no systematic regional inventory was attempted until the time of Dr. -

Indian Philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article

Indian philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article Indian philosophy the systems of thought and reflection that were developed by the civilizations of the Indian subcontinent. They include both orthodox (astika) systems, namely, the Nyaya, Vaisesika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva-mimamsa, and Vedanta schools of philosophy, and unorthodox (nastika) systems, such as Buddhism and Jainism. Indian thought has been concerned with various philosophical problems, significant among them the nature of the world (cosmology), the nature of reality (metaphysics), logic, the nature of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and religion. General considerations Significance of Indian philosophies in the history of philosophy In relation to Western philosophical thought, Indian philosophy offers both surprising points of affinity and illuminating differences. The differences highlight certain fundamentally new questions that the Indian philosophers asked. The similarities reveal that, even when philosophers in India and the West were grappling with the same problems and sometimes even suggesting similar theories, Indian thinkers were advancing novel formulations and argumentations. Problems that the Indian philosophers raised for consideration, but that their Western counterparts never did, include such matters as the origin (utpatti) and apprehension (jñapti) of truth (pramanya). Problems that the Indian philosophers for the most part ignored but that helped shape Western philosophy include the question of whether knowledge arises from experience or from reason and distinctions such as that between analytic and synthetic judgments or between contingent and necessary truths. Indian thought, therefore, provides the historian of Western philosophy with a point of view that may supplement that gained from Western thought. A study of Indian thought, then, reveals certain inadequacies of Western philosophical thought and makes clear that some concepts and distinctions may not be as inevitable as they may otherwise seem. -

Hinduism and Social Work

5 Hinduism and Social Work *Manju Kumar Introduction Hinduism, one of the oldest living religions, with a history stretching from around the second millennium B.C. to the present, is India’s indigenous religious and cultural system. It encompasses a broad spectrum of philosophies ranging from pluralistic theism to absolute monism. Hinduism is not a homogeneous, organized system. It has no founder and no single code of beliefs; it has no central headquarters; it never had any religious organisation that wielded temporal power over its followers. Hinduism does not have a single scripture as the source of its various teachings. It is diverse; no single doctrine (or set of beliefs) can represent its numerous traditions. Nonetheless, the various schools share several basic concepts, which help us to understand how most Hindus see and respond to the world. Ekam Satya Viprah Bahuda Vadanti — “Truth is one; people call it by many names” (Rigveda I 164.46). From fetishism, through polytheism and pantheism to the highest and the noblest concept of Deity and Man in Hinduism the whole gamut of human thought and belief is to be found. Hindu religious life might take the form of devotion to God or gods, the duties of family life, or concentrated meditation. Given all this diversity, it is important to take care when generalizing about “Hinduism” or “Hindu beliefs.” For every class of * Ms. Manju Kumar, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, Delhi University, Delhi. 140 Origin and Development of Social Work in India worshiper and thinker Hinduism makes a provision; herein lies also its great power of assimilation and absorption of schools of philosophy and communities of people, (Theosophy, 1931). -

Book Only Cd Ou160053>

TEXT PROBLEM WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY CD OU160053> Vedant series. Book No. 9. English aeries (I) \\ A hand book of Sri Madhwacfaar^a's POORNA-BRAHMA PH I LOSOPHY by Alur Venkat Rao, B.A.LL,B. DHARWAR. Dt. DHARWAR. (BOM) Publishers : NAYA-JEEYAN GRANTHA-BHANDAR, SADHANKERI, DHARWAR. ( S.Rly ) Price : Superior : 7 Rs. 111954 Ordinary: 6 Rs. (No postage} Publishers: Nu-va-Jeevan Granth Bhandar Dharwar, (Bombay) Printer : Sri, S. N. Kurdi, Sri Saraswati Printing Press, Dharwar. ,-}// rights reserved by the author. To Poorna-Brahma Dasa; Sri Sri : Sri Madhwacharya ( Courtesy 1 he title of my book is rather misleading for though the main theme of the book is Madhwa philosophy, it incidentally and comparitively deals with other philosophies such as that of Sri Shankara Sri Ramanuja and Sri Mahaveer etc. So, it is use- ful for all those who are interested in such subjects. Sri Madhawacharya, the foremost Vaishnawa philosopher, who is the last of the three great Teachers,- Sri Shankara, Sri Ramanuja and Sri Madhwa,- is so far practically unknown to the English-reading public of India. This is, therefore the first attempt to present his philosophy to the wider public. Madhwa philosophy has got two aspects, one universal and the other, particular. I have tried to place before the readers both these aspects. I have re-assessed the values of Madhwa and other philosophies, and have tried to find out also the greatest common factor,-an angle of vision which has not been systematically adopted by any body. He is a great Harmoniser. In fact mine isS quite a new approach, I have tried to put old things in a new way.