Caste, Desire, and the Representation of the Gendered Other in U. R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samskara-By-Ur-Anantha-Murthy.Pdf

LITERATURE ~O} OXFORD"" Made into a powerful, award-winning film in 1970, this important Kannada novel of the sixties has received widespread acclaim from both critics and general read ers since its first publication in 1965. As a religious novel about a decaying brahmin colony in the south Indian village of Karnataka, Samskara serves as an allegory rich in realistic detail, a contemporary reworking of ancient Hindu themes and myths, and a serious, poetic study of a religious man living in a community of priests gone to seed. A death, which stands as the central event in the plot, brings in its wake a plague, many more deaths, live questions with only dead answers, moral chaos, and the rebirth of one man. The volume provides a useful glos sary of Hindu myths, customs, Indian names, flora, and other terms. Notes and an afterword enhance the self contained, faithful, and yet readable translation. U.R. Anantha Murthy is a well-known Indian novelist. The late A.K. Ramanujan w,as William E. Colvin Professor in the Departments of South Asian Languages and Civilizations and of Linguistics at the University of Chicago. He is the author of many books, including The Interior Landscape, The Striders, The Collected Poems, and· several other volumes of verse in English and Kannada. ISBN 978-0-19-561079-6 90000 Cover design by David Tran Oxford Paperbacks 9780195 610796 Oxford University Press u.s. $14.95 1 1 SAMSKARA A Rite for a Dead Man Sam-s-kiira. 1. Forming well or thoroughly, making perfect, perfecting; finishing, refining, refinement, accomplishment. -

Fairs and Festivals, Part VII-B

PM. 179.9 (N) 750 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II ANDHRA PRADESII PART VII-B (9) A. CHANDRA SEKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh Price: Rs. 5.75 P. or 13 Sh. 5 d. or 2 $ 07 c. 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH (All the Census Publications of this State will bear Vol. No. II) J General Report PART I I Report on Vital Statistics (with Sub-parts) l Subsidiary Tables PART II-A General Population Tables PART II-B (i) Economic Tables [B-1 to B-IVJ PART II-B (ii) Economic Tables [B-V to B-IX] PART II-C Cultural and Migration Tables PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishme"nts (with Subsidiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Village Survey Monographs PART VII-A tIn Handicraft Survey Reports (Selected Crafts) PART VII-A (2) f PA&T VII-B Fairs and Festivals PART VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration } (Not for PART VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation Sale) PART IX Maps PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City PHOTO PLATE I Tower at the entrance of Kodandaramaswamy temple, Vontimitta. Sidhout Tdluk -Courtesy.- Commissioner for H. R. & C. E. (Admn. ) Dept., A. p .• Hydcrabad. F 0 R,E W 0 R D Although since the beginning of history, foreign traveller~ and historians have recorded the principal marts and ~ntrepot1'l of commerce in India and have even mentioned important festival::» and fairs and articles of special excellence availa ble in them, no systematic regional inventory was attempted until the time of Dr. -

Girish Kasaravalli Film Festival 25 / 26 / 27 / 28 / 29 July 2015

Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Bengaluru Presents Girish Kasaravalli Film Festival 25 / 26 / 27 / 28 / 29 July 2015 • Gulabi Talkies • Naayi Neralu • Kraurya • Thayi Saheba • Ghatashraddha • Tabarana Kathe • Dweepa • Kanasembo Kudureyaneri • Haseena • Koormavatara Photo Exhibition on Girish Kasaravalli organised by Sri. K.S. Rajaram, Noted Photographer Venue : Khincha Auditorium, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Race Course Road, Bengaluru - 560 001 All are cordially Invited Girish Kasaravalli Girish Kasaravalli (December 3, 1950) is a ilm director of the Kannada cinema, and a pioneer of the parallel cinema movement. Known internationally, he has won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film four times - Ghatashraddha (1977), Tabarana Kathe (1986), Thaayi Saheba (1997) and Dweepa (2002). In 2011, he was awarded Padma Shri, the fourth highest civilian award by Government of India. A gold medalist from the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune, Kasaravalli started his career in ilms with Ghatashraddha (1977). Over the next 30 years he directed 11 ilms and a tele serial. The ilm he made to fulill his diploma, Avashesh, was awarded the Best Student Film and the National Film Award for Best Short Fiction Film for that year. He has received thirteen National Film Awards. The International Film Festival of Rotterdam held a retrospective of Girish Kasaravalli's ilms in 2003. Girish Kasaravalli Film Festival - 2015 - Calendar of Events July 25, 2015, Saturday Programme 10.30 a.m. Inauguration : Smt. Umashri Hon’ble Minister for Kannada and Culture, Women and Child Development, Govt. of Karnataka Chief Guests : Dr. L. Hanumanthaiah, Ex MLC, Chairman, Kannada Development Authority Dr. Vijaya, Noted Film Journalist Smt. -

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava Sampradaya Connected to the Madhva Line?

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? – Jagadananda Das – The relationship of the Madhva-sampradaya to the Gaudiya Vaishnavas is one that has been sensitive for more than 200 years. Not only did it rear its head in the time of Baladeva Vidyabhushan, when the legitimacy of the Gaudiyas was challenged in Jaipur, but repeatedly since then. Bhaktivinoda Thakur wrote in his 1892 work Mahaprabhura siksha that those who reject this connection are “the greatest enemies of Sri Krishna Chaitanya’s family of followers.” In subsequent years, nearly every scholar of Bengal Vaishnavism has cast his doubts on this connection including S. K. De, Surendranath Dasgupta, Sundarananda Vidyavinoda, Friedhelm Hardy and others. The degree to which these various authors reject this connection is different. According to Gaudiya tradition, Madhavendra Puri appeared in the 14th century. He was a guru of the Brahma or Madhva-sampradaya, one of the four (Brahma, Sri, Rudra and Sanaka) legitimate Vaishnava lineages of the Kali Yuga. Madhavendra’s disciple Isvara Puri took Sri Krishna Chaitanya as his disciple. The followers of Sri Chaitanya are thus members of the Madhva line. The authoritative sources for this identification with the Madhva lineage are principally four: Kavi Karnapura’s Gaura-ganoddesa-dipika (1576), the writings of Gopala Guru Goswami from around the same time, Baladeva’s Prameya-ratnavali from the late 18th century, and anothe late 18th century work, Narahari’s -

Reflecting Women's Suffering, Redefining Cultural Spaces

Kasaravalli’s three women Reflecting women’s suffering, redefining cultural spaces He spins the yarn of kannada cinema with celebrative passion and single-minded dedication, salubrious novelty and lofty ideals. Time and again, he has hit the silver screen with surprising charm of his humane characters, the lives they bring on themselves and the lives that the external world imposes on them. His is a dynamic cinematic space which evolves in a vibrant dialogue or exchange with the literary, theatre, and essentially, social movements. And his works are deeply rooted in its cultural milieu and sensitive to its socio-political surroundings. Drawing inspiration from Italian neo-realism and the Navya literary movement, he, Girish Kasaravalli, has made remarkable contribution to the New Wave Cinema, both in thematic concerns and aesthetic sensibility. Alongside, Kasaravalli’s works bear ample testimony to his indomitable spirit of experimentation with the film form and content. Unfortunately, Kasaravalli is one of the most neglected great directors of our times. Though his film Ghatashraddha is the only Indian film to have featured in the Paris Cinematheque’s list of 100 best films of 100 years of world cinema and is ranked at 56, he has hardly received the due recognition in his own soil. Recently, his film Kanasembo Kudureyanneri has bagged NETPA Jury award as the best Asian film of 2010 at the Asiatica Film Mediale Film Festival of Rome. In 2009, he has been awarded South Asian Cinema Foundation's 'Excellence in Cinema' Crystal Globe Award 2009 at United Kingdom, the citation of which states that his films right from Ghatashraddha to Gulabi Talkies have mirrored the social conflicts in the six decades of Karnataka. -

Seritechnics

SeriTechnics Historical Silk Technologies Edition Open Access Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Samuel Gfrörer, Klaus Thoden, Malte Vogl The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publication ini tiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines tra ditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the openaccess publica tions of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initia tives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. SeriTechnics Historical Silk Technologies Dagmar Schäfer, Giorgio Riello, and Luca Molà (eds.) Studies 13 Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Studies 13 Editorial Team: Gina PartridgeGrzimek with Melanie Glienke and Wiebke Weitzmann Cover Image: © The British Library Board. (Yongle da dian 永樂大典 vol. -

Dvaita Vedanta

Dvaita Vedanta Madhva’s Vaisnava Theism K R Paramahamsa Table of Contents Dvaita System Of Vedanta ................................................ 1 Cognition ............................................................................ 5 Introduction..................................................................... 5 Pratyaksa, Sense Perception .......................................... 6 Anumana, Inference ....................................................... 9 Sabda, Word Testimony ............................................... 10 Metaphysical Categories ................................................ 13 General ........................................................................ 13 Nature .......................................................................... 14 Individual Soul (Jiva) ..................................................... 17 God .............................................................................. 21 Purusartha, Human Goal ................................................ 30 Purusartha .................................................................... 30 Sadhana, Means of Attainment ..................................... 32 Evolution of Dvaita Thought .......................................... 37 Madhva Hagiology .......................................................... 42 Works of Madhva-Sarvamula ......................................... 44 An Outline .................................................................... 44 Gitabhashya ................................................................ -

OIOP Nov 2018

Vol 22/04 Nov 2018 Patriotism Redefined Indian Archaeology, 2018 know india better The stunning ruins of Hampi The fascinating world of archaeology The startling story of Ajanta FACE TO FACE Excavating of Nagardhan Dr. Arvind P. Jamkhedkar Great Indians : Kavi Gopaldas ‘Neeraj’ | Annapurna Devi | Captain Sunil Kumar Chaudhary, KC, SM MORPARIA’S PAGE Contents November 2018 VOL. 22/04 THEME: Morparia’s Page 02 INDIAN The fascinating world of archaeology 04 ARCHAEOLOGY, 2018 Dr. Kaushik Gangopadhyay Managing Editor The startling story of Ajanta 07 Mrs. Sucharita R. Hegde Shubha Khandekar Excavating of Nagardhan 09 Abhiruchi Oke Editor The mute witnesses 11 Anuradha Dhareshwar Harshada Wirkud The footprints of the caveman 14 Satish Lalit Assistant Editor The Deccan discovery 16 E.Vijayalakshmi Rajan Varada Khaladkar Jaina basadis of North Karnataka 30 Abdul Aziz Rajput Design Resurgam Digital LLP Know India Better The stunning ruins of Hampi 17 Usha Hariprasad Subscription In-Charge Nagesh Bangera Face to Face Dr. Arvind P. Jamkhedkar 25 Raamesh Gowri Raghavan Advisory Board Sucharita Hegde General Justice S. Radhakrishnan Venkat R. Chary Killing a Tigress 32 Harshad Sambhamurthy Paper cups, not a choice 34 Usha Hariprasad Printed & Published by Mrs. Sucharita R. Hegde for One India One People Foundation, Mahalaxmi Chambers, 4th floor, Great Indians 36 22, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Mumbai - 400 026 Tel: 022-2353 4400 Fax: 022-2351 7544 e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] visit us at: KAVI GOPALDAS “NEERAJ” ANNAPURNA DEVI CAPTAIN SUNIL KUMAR www.oneindiaonepeople.com CHAUDHARY, KC, SM www.facebook.com/oneindiaonepeoplefoundation INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY, 2018 The fascinating world of archaeology The field of archaeology in India still exhibits a colonial hangover. -

Philosophy of Sri Madhvacarya

PHILOSOPHY OF SRI MADHVAGARYA by Vidyabhusana Dr. B. N. K. SHARMA, m. a., Ph. d., Head of the Department of Sanskrit and Ardhamagadhl, Ruparel College, Bombay- 16. 1962 BHARATIYA VIDYA BHAVAN BOMBAY-7 Copyright and rights of translation and reproduction reserved by the author.. First published.' March, 1962 Pri/e Rs. 15/- Prlnted in India By h. G. Gore at the Perfecta Printing Works, 109A, Industrial Aiea, Sion, Bombay 22. and published by S. Ramakrishnan, Executive Secrelaiy Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay 1. Dedicated to &R1 MADHVACARYA Who showed how Philosophy could fulfil its purpose and attain its goal by enabling man to realize the eternal and indissoluble bond of Bitnbapratibimbabhava that exists between the Infinite and the finite. ABBREVIATIONS AV. Anu-Vyakhyana Bhag. Bhagavata B. T. Bhagavata-Tatparya B. S. Brahma-Sutra B. S. B. Brahmasutra Bhasya Brh. Up. Brhadaranyaka-Upanisad C. Commentary Chan. Up. Chandogya Upanisad Cri. Sur. I. Phil. A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy D. M. S. Daivi Mimamsa Sutras I. Phil. Indian Philosophy G. B. Glta-Bha»sya G. T. Glta-Tatparya KN. Karma-Nirnaya KN. t. Karma Nirpaya Tika M. G. B. Madhva's GTta Bhasya M. Vij. Madhvavijaya M. S. Madhvasiddhantasara Mbh. Mahabharata Mbh. T. N. Mahabharata Tatparya Nirnaya Man. Up. Mandukya Upanisad Mith. Kh.t. Mithyatvanumana Khandana Tika Mund.Up. Mundaka Upanisad Nym- Nyayamrta NS. Nyaya Sudha NV. Nyaya Vivarapa PP- Pramana Paddhati P- M. S. Purva Mlmamsa Sutras R- V. Rg Veda R.G.B. Ramanuja's Glta Bhasya S. N. R. Sannyaya Ratnavalf Svet. Up. Svetaivatara Upanisad Tg. ( Nyayamrta )-Tarangini TS. -

Being Brahmin, Being Modern

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 Being Brahmin, Being Modern Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 ii (Blank) Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 Being Brahmin, Being Modern Exploring the Lives of Caste Today Ramesh Bairy T. S. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 First published 2010 by Routledge 912–915 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2010 © 2010 Ramesh Bairy T. S. Typeset by Bukprint India B-180A, Guru Nanak Pura, Laxmi Nagar Delhi 110 092 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-58576-7 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 For my parents, Smt. Lakshmi S. Bairi and Sri. T. Subbaraya Bairi. And, University of Hyderabad. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 vi (Blank) Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:12 24 May 2016 Contents Acknowledgements ix Chapter 1 Introduction: Seeking a Foothold -

Government First Grade Collegeand Centre for Pg Studies, Thenkanidiyur

Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education GOVERNMENT FIRST GRADE COLLEGEAND CENTRE FOR PG STUDIES, THENKANIDIYUR, UDUPI INTERNAL QUALITY ASSURANCE CELL LESSON PLAN FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR - 2019-20 Government of Karnataka Department of Collegiate Education Government First Grade College Centre for PG Studies, Thenkanidiyur LESSON PLAN FOR THE ACADEMIC YEAR - 2019-20 MA- I and II SEMESTERS III BA- V and VI SEMESTERS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (ANNEXURE-1.2) Criterion 01 (Metric -1.1.1) Programme: I MA HISTORY AND III BA Course/Paper Name: 1. HS.401: Society and Economy in Early India (up to 2nd C.E). -4HRS 2. HS.403: Colonialism in India. – 4 HRS 3. HS.404: Introduction to Archaeology, Epigraphy and Numismatics. – 4HRS 4. HS.405: Economic and Social Processes in Medieval Karnataka. -2 HRS 5. 051: Colonial India (III BA)- 2HRS Name of the Faculty: DR. SURESH RAI.K Total Hours: 04+4+4+2=16 HRS PER WEEK. SL. TOPIC COVERED NO. OF METHODOLOGY/PED DATE INITIAL NO. LECTURE AGOGY HOURS I HS.401: Society and Economy in Early India (up to 2nd C.E). - 4HRS 1 Unit 1: Historiographical 8HRS 16-7-2019 SRAI Considerations: State and LECTURE METHOD TO Society as represented in SEMINARS 31-7-2019 Colonial writings – Oriental PPT Despotism and Asiatic CLASS TEST Society the nationalist response–Marxist intervention. 2 Unit 2: The Harappan 14HRS 1-8-2019 SRAI Society: Harappan LECTURE METHOD TO Traditions- Archaeological SEMINARS -

Difference Is Real”

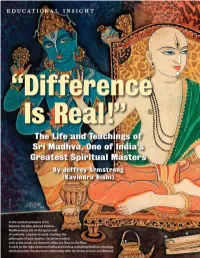

EDUCATIONAL INSIGHT The Life and Teachings of Sri Madhva, One of India’s Greatest Spiritual Masters By Jeffrey Armstrong (Kavindra Rishi) s. rajam In the constant presence of his Beloved, the blue-skinned Krishna, Madhvacharya sits on the guru’s seat of authority, scripture in hand, teaching the philosophy of pure dualism. Sectarian symbols, such as the conch, are drawn in white rice fl our on the fl oor. A nitch on the right enshrines Radha and Krishna, indicating Madhva’s theology, which describes the devotee’s relationship with the Divine as lover and Beloved. july/august/september, 2008 hinduism today 39 The Remarkable Life of Sri Madhvacharya icture a man off powerfulf physique, a champion wrestler, who They are not born and do not die, though they may appear to do so. tiny platform,f proclaimedd to the crowdd off devoteesd that Lordd Vayu, Vasudeva was physically and mentally precocious. Once, at the could eat hundreds of bananas in one sitting. Imagine a guru Avatars manifest varying degrees of Divinity, from the perfect, or the closest deva to Vishnu, would soon take birth to revive Hindu age of one, he grabbed hold of the tail of one of the family bulls who P who was observed to lead his students into a river, walk them Purna-Avatars, like Lord Rama and Lord Krishna, to the avatars of dharma. For twelve years, a pious brahmin couple of modest means, was going out to graze in the forest and followed the bull all day long. across the bottom and out the other side.