Best Practice Guidelines for the Re-Introduction of Great Apes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Gorilla Beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26

Gorilla beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia ChordataMammaliaPrimatesHominidae Scientific Gorilla beringei Name: Species Matschie, 1903 Authority: Infra- specific See Gorilla beringei ssp. beringei Taxa See Gorilla beringei ssp. graueri Assessed: Common Name(s): English –Eastern Gorilla French –Gorille de l'Est Spanish–Gorilla Oriental TaxonomicMittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B. and Wilson D.E. 2013. Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume Source(s): 3 Primates. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. This species appeared in the 1996 Red List as a subspecies of Gorilla gorilla. Since 2001, the Eastern Taxonomic Gorilla has been considered a separate species (Gorilla beringei) with two subspecies: Grauer’s Gorilla Notes: (Gorilla beringei graueri) and the Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) following Groves (2001). Assessment Information [top] Red List Category & Criteria: Critically Endangered A4bcd ver 3.1 Year Published: 2016 Date Assessed: 2016-04-01 Assessor(s): Plumptre, A., Robbins, M. & Williamson, E.A. Reviewer(s): Mittermeier, R.A. & Rylands, A.B. Contributor(s): Butynski, T.M. & Gray, M. Justification: Eastern Gorillas (Gorilla beringei) live in the mountainous forests of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, northwest Rwanda and southwest Uganda. This region was the epicentre of Africa's "world war", to which Gorillas have also fallen victim. The Mountain Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei beringei), has been listed as Critically Endangered since 1996. Although a drastic reduction of the Grauer’s Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei graueri), has long been suspected, quantitative evidence of the decline has been lacking (Robbins and Williamson 2008). During the past 20 years, Grauer’s Gorillas have been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for bushmeat associated with artisanal mining camps and for commercial trade (Plumptre et al. -

Novo Terapeutisk Laboratorium

Novo Terapeutisk Laboratorium 20. 04. 2020 Bevaringsplan Bygherre Byggeselskab Mogens de Linde A/S Udarbejdet af Elgaard Architecture A/S Indhold Byggesagsorganisation 4 Indledning 5 Del 1 - Analyse Historiske hovedtræk Frederiksbergs udvikling – kort historisk rids 7 Novos Bygninger i byområdet 9 Novo Terapeutisk Laboratorium - historien 11 Arkitekt Arne Jacobsen og hans samarbejde med Novo 13 Novo Terapeutisk Laboratorium - Historie og ombygninger 15 Eksisterende forhold Registrering Området 17 Terræn og haveanlæg 19 Bygninger og bygningsændringer 21 Byggeteknisk analyse / overordnet tilstand 31 Værdisætning Miljømæssig værdi 32 Kulturhistorisk værdi 33 Arkitektonisk værdi 34 Bærende bevaringsværdier 35 Del 2 - Udvikling Udvikling og bevaringsstrategi Bevaringsstrategi som ramme for fremtidig udvikling 37 Bevaringsprincipper for eksisterende facader 45 Samenfatning 49 Bilag Originaltegninger indhentes fra Kunstakademiets bibliotek og Rigsarkivet side 3 / 49 Byggesagsorganisation Byggesagsorganisation Bygherre Byggeselskab Mogens de Linde A/S Jens Baggesens Vej 88F, 2 8200 Aarhus N Mogens de Linde [email protected] +45 40 29 65 70 Arkitekt, bevaringsplan Elgaard Architecture A/S Rigensgade 11, 1. tv. 1316 København K Peder Elgaard [email protected] +45 26 70 85 84 Julian Jahn [email protected] +45 22 93 43 18 Arkitekt, nybyggeri Gjøde og Partnere Arkitekter Høegh-Guldbergs Gade 65 8000 Aarhus C Johan Gjøde [email protected] +45 28 97 65 38 side 4 / 49 Indledning Med sin historie og høje arkitektoniske kvalitet, hersker der en helt særlig Novo-ånd på stedet, en helt særlig identitet. Novo ejendommen på Fuglebakkevej er på mange måder historisk. Novo Terapeutisk Laboratorium blev grundlagt i 1927, og grundet stor fremgang, flytter firmaet allerede i 1932 til den nuværende adresse på Fuglebakkevej/Nordre Fasanvej. -

Surrogate Motherhood

Surrogate Motherhood Page ii MEDICAL ETHICS SERIES David H. Smith and Robert M. Veatch, Editors Page iii Surrogate Motherhood Politics and Privacy Edited by Larry Gostin Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Page iv This book is based on a special issue of Law, Medicine & Health Care (16:1–2, spring/summer, 1988), a journal of the American Society of Law & Medicine. Many of the essays have been revised, updated, or corrected, and five appendices have been added. ASLM coordinator of book production was Merrill Kaitz. © 1988, 1990 American Society of Law & Medicine All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permission constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1984. Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Surrogate motherhood : politics and privacy / edited by Larry Gostin. p. cm. — (Medical ethics series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0253326044 (alk. paper) 1. Surrogate mothers—Legal status, laws, etc.—United States. 2. Surrogate mothers—Civil rights—United States. 3. Surrogate mothers—United States. I. Gostin, Larry O. (Larry Ogalthorpe) II. Series. KF540.A75S87 1990 346.7301'7—dc20 [347.30617] 8945474 CIP 1 2 3 4 5 94 93 92 91 90 Page v Contents Introduction ix Larry Gostin CIVIL LIBERTIES A Civil Liberties Analysis of Surrogacy Arrangements 3 Larry Gostin Procreative Liberty and the State's Burden of Proof in Regulating Noncoital 24 Reproduction John A. -

Student Handbook Welcome to Isup

ISUP 2019 2 INTERNATIONAL SUMMER UNIVERSITY PROGRAMME STUDENT HANDBOOK WELCOME TO ISUP Congratulations on your acceptance to the International Summer INTERNATIONAL SUMMER UNIVERSITY PROGRAMME NICE TO KNOW University Programme (ISUP) 2019. We look forward to welcoming 3 Contact information 23 Cell phones you to Copenhagen Business School (CBS). 3 Facebook 23 Currency 3 Academic information 23 Electricity You will soon be starting a new educational experience, and we 5 ISUP academic calendar 2019 25 Grants hope that this handbook will help you through some of the practical 25 Social Programme PREPARING FOR YOUR STAY aspects of your stay in Denmark. You will find useful and practical 25 Temporary lodging information, tips and facts about Denmark and links to pages to get 7 Introduction 25 Leisure time even more information. 7 Passport / short term visa 27 Transportation 9 Health insurance You would be wise to spend time perusing all the information, as it 9 Accommodation ABOUT DENMARK will make things so much easier for you during ISUP. 31 Geography ARRIVING AT CBS 33 Monarchy If this booklet does not answer all of your questions or dispel every 11 Arrival in Copenhagen 33 Danish language uncertainty, our best advice is simply to ask one of your new Danish 11 Email 33 The national flag classmates! They often know better than any handbook or us at the 11 Laptops 33 The political system ISUP secretariat, so do not be afraid to ask for help and information 11 Textbooks 33 International cooperation when needed. This is also the best cultural way to become acquainted 11 Student ID card 35 Education with Danes and make new friends while you are here. -

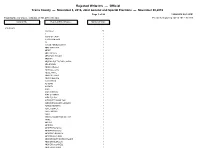

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Livability Court Records 1/1/1997 to 8/31/2021

Livability Court Records 1/1/1997 to 8/31/2021 Last First Middle Case Charge Disposition Disposition Date Judge 133 Cannon St Llc Rep JohnCompany Q Florence U43958 Minimum Standards For Vacant StructuresGuilty 8/13/18 Molony 148 St Phillips St Assoc.Company U32949 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 10/17/11 Molony 18 Felix Llc Rep David BevonCompany U34794 Building Permits; Plat and Plans RequiredGuilty 8/13/18 Mendelsohn 258 Coming Street InvestmentCompany Llc Rep Donald Mitchum U42944 Public Nuisances Prohibited Guilty 12/18/17 Molony 276 King Street Llc C/O CompanyDiversified Corporate Services Int'l U45118 STR Failure to List Permit Number Guilty 2/25/19 Molony 60 And 60 1/2 Cannon St,Company Llc U33971 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 8/29/11 Molony 60 Bull St Llc U31469 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 8/29/11 Molony 70 Ashe St. Llc C/O StefanieCompany Lynn Huffer U45433 STR Failure to List Permit Number N/A 5/6/19 Molony 70 Ashe Street Llc C/O CompanyCobb Dill And Hammett U45425 STR Failure to List Permit Number N/A 5/6/19 Molony 78 Smith St. Llc C/O HarrisonCompany Malpass U45427 STR Failure to List Permit Number Guilty 3/25/19 Molony A Lkyon Art And Antiques U18167 Fail To Follow Putout Practices Guilty 1/22/04 Molony Aaron's Deli Rep Chad WalkesCompany U31773 False Alarms Guilty 9/14/16 Molony Abbott Harriet Caroline U79107 Loud & Unnecessary Noise Guilty 8/23/10 Molony Abdo David W U32943 Improper Disposal of Garbage/Trash Guilty- Residential 8/29/11 Molony Abdo David W U37109 Public Nuisances Prohibited Guilty 2/11/14 Pending Abkairian Sabina U41995 1st Offense - Failing to wear face coveringGuilty or mask. -

Himpanzee C Chronicle

An Exclusive Publication Produced By Chimp Haven, Inc. VOLUME IX ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2009 HIMPANZEE www.chimphaven.org C CHRONICLE INSIDE THIS ISSUE: PET CHIMPANZEES HAVE BEEN IN THE NEWS THIS YEAR. Travis, who attacked a woman in Connecticut, was shot to death. Timmie was shot in Missouri when he escaped and attacked a deputy. There are countless more pet chimpanzees living in private homes throughout the United States. This edition of the Chimpanzee Chronicle discusses this serious issue. Please share it with others. WHY CHIMPANZEES DON’T MAKE GOOD PETS By Linda Brent, PhD, President and Director When chimpanzees become pets, the outcome for them or their human “family” is rarely a good one. Chimpanzees are large, wild animals who are highly intelligent and require a great deal of socialization with their mother and other chimpanzees. Sanctuaries most often hear about pet chimpanzees when they reach adolescence and are too difficult to manage any longer. Often, they bite someone or break household items. Sometimes they get loose or seriously attack a person. Generally speaking, these actions are part of normal chimpanzee behavior. An adolescent male chimpanzee begins to try to dominate others as he works his way up the dominance hierarchy or social ladder. He does this by BOARD OF displaying, hitting and throwing objects, and sometimes attacking others. Pet chimpanzees do not have the benefit of a normal social group as an outlet for their behavior, and often these DIRECTORS behaviors are directed at human caregivers or strangers. Since chimpanzees can easily weigh as much as a person—but are far stronger—they are obviously dangerous animals to have in the Thomas Butler, D.V.M., M.S. -

What to Know and Where to Go

What to Know and Where to Go A Practical Guide for International Students at the Faculty of Science CONTENT 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................8 2. WHO TO CONTACT? ................................................................................................................................................ 9 FULL-DEGREE STUDENTS: ......................................................................................................................................9 GUEST/EXCHANGE STUDENTS: ........................................................................................................................... 10 3. ACADEMIC CALENDAR AND TIMETABLE GROUPS .................................................................................... 13 NORMAL TEACHING BLOCKS ........................................................................................................................................ 13 GUIDANCE WEEK ......................................................................................................................................................... 13 THE SUMMER PERIOD ................................................................................................................................................... 13 THE 2009/2010 ACADEMIC YEAR ................................................................................................................................. 14 HOLIDAYS & PUBLIC -

Supreme Court of the State of New York County of New York ______

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK __________________________________________________ In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, MEMORANDUM OF Petitioner, LAW IN SUPPORT OF -against- PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. Index No. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents. __________________________________________________ Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5 Dunhill Road New Hyde Park, NY 11040 Phone (516) 747-4726 Steven M. Wise, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5195 NW 112th Terrace Coral Springs, FL 33076 Phone (954) 648-9864 Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. Subject to pro hac vice admission January_____, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................ v I. SUMMARY OF NEW GROUNDS AND FACTS NEITHER PRESENTED NOR DETERMINED IN NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., EX REL. KIKO v. PRESTI OR NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC. ON BEHALF OF TOMMY v. LAVERY. ............................................................................................................. 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................... 6 III. STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................... -

Hunters and Farmers in the North – the Transformation of Pottery Traditions

Hunters and farmers in the North – the transformation of pottery traditions and distribution patterns of key artefacts during the Mesolithic and Neolithic transition in southern Scandinavia Lasse Sørensen Abstract There are two distinct ceramic traditions in the Mesolithic (pointed based vessels) and Neolithic (flat based vessels) of southern Scandinavia. Comparisons between the two ceramic traditions document differences in manufacturing techniques, cooking traditions and usage in rituals. The pointed based vessels belong to a hunter-gatherer pottery tradition, which arrived in the Ertebølle culture around 4800 calBC and disappears around 4000 calBC. The flat based vessels are known as Funnel Beakers and belong to the Tragtbæger (TRB) culture, appearing around 4000 calBC together with a new material culture, depositional practices and agrarian subsistence. Pioneering farmers brought these new trends through a leap- frog migration associated with the Michelsberg culture in Central Europe. These arriving farmers interacted with the indigenous population in southern Scandinavia, resulting in a swift transition. Regional boundaries observed in material culture disappeared at the end of the Ertebølle, followed by uniformity during the earliest stages of the Early Neolithic. The same boundaries reappeared again during the later stages of the Early Neolithic, thus supporting the indigenous population’s important role in the neolithisation process. Zusammenfassung Keywords: Southern Scandinavia, Neolithisation, Late Ertebølle Culture, Early -

Cloudburst Masterplan for Ladegårdså, Frederiksberg East & Vesterbro

SUMMARY CLOUDBURST MASTERPLAN FOR LADEGÅRDSÅ, FREDERIKSBERG EAST & VESTERBRO RESUMÉ KONKRETISERING AF SKYBRUDSPLAN Ladegårdsåen og Vesterbro CLOUDBURST CATCHMENTS The very severe cloudburst hitting Copenhagen the 2nd of July 2011 caused flooding in large portions of the city. The flooding caused significant problems for the infrastructure in the NH inner parts of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg. In certain places up to half a meter of water covered the street and several houses and shops had suffered serious damages. Brønshøj - Husum Østerbro Bispebjerg ØSTERBRO The serious consequences following the cloudburst on July 2nd 2011 and other minor cloudbursts have led the municipalities of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg to initiate this project, Nørrebro which aims to highlight potential initiatives effective in mitigating flooding and reducing damages related to Ladegårdså cloudbursts in the future. Vanløse- INDREIndre BY by The cloudburst solutions presented here cover the Frederiksberg Vest Frederiksberg Øst CH catchments of Ladegårdså, Frederiksberg East & Vesterbro. The proposed solutions for cloudburst management comply with the service level for cloudbursts in Copenhagen and Frederiksberg, ie. a maximum of 10 cm of water on terrain Vesterbro during a 100-year storm event. Additionally, in accordance with the intentions and visions set out in the Cloudburst Plan for Copenhagen and Frederiksberg from 2012, proposed Amager solutions are sought developed to include added value and Valby - SH elements, which contribute to making the city more green, Frederiksberg Sydvest more blue, more attractive and more liveable. The cloudburst catchments are prioritized based on an assessment of the flood risks in the individual catchments. Along with the Inner City (Indre by) & Østerbro, the Ladegårdså, Frederiksberg East & Vesterbro catchment belongs to catchments of highest priority.