Title of Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education, Politics and Organisation: The

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. TRANSFORMATION 15 (1991) ARTICLE \ EDUCATION, POLITICS AND ORGANISATION THE EDUCATIONAL TRADITIONS AND LEGACIES OF THE NON-EUROPEAN UNITY MOVEMENT, 1943-1986* Linda Chisholm The political culture of the.Western Cape, so any writer or visitor to the city of Cape Town and beyond will attest, is distinctive from that characterising the rest of the country. Wherever one stands on the organised political spectrum, it is distinc- tive for its combativeness, its intellectual assertiveness, and its critical disposition. Of course not all Western Cape activists or trade unionists are combative, or display critically enquiring minds. Nor are these qualities always an indisputable 'good'. Nonetheless, whatever the reservations and qualifications, it can be said that the political style of the Western Cape is distinctive. And it is remarkable. Sufficiently remarkable that it ought to be written about. The reasons for this distinctive character are of course complex and varied. Amongst these the political style and traditions established by the Non-European Unity Movement which grew out of the Anti-Coloured Affairs Department (Anti- CAD) campaign of the early 1940s must be included. It must be stressed that this is not the only, or even most significant political movement in the Western Cape; nor does it account for traditions that may have developed in the African townships. -

It Is the Parents' Responsibility to Contact the High Schools of Their Choice and to Collect and Return Application Forms to These Schools

VERY IMPORTANT IT IS THE PARENTS’ RESPONSIBILITY TO CONTACT THE HIGH SCHOOLS OF THEIR CHOICE AND TO COLLECT AND RETURN APPLICATION FORMS TO THESE SCHOOLS. YOU MUST APPLY TO MORE THAN ONE SCHOOL—(AT LEAST FIVE SCHOOLS) WE CANNOT ASSIST YOU IN PLACING A CHILD IN A HIGH SCHOOL YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE TO ENSURE THAT YOU HAVE MADE APPLICATIONS HIGH SCHOOLS FOR GRADE 7'S HIGH SCHOOL FEES P/A DEADLINE AS PER WCED THEY HAVE OUTLINED DEADLINES FOR ADMISSION TO ORDINARY PUBLIC SCHOOLS FOR 2020. SCHOOL ADMISSIONS OPEN 1 FEBRUARY 2019 AND CLOSES ON 15 MARCH 2019 (THIS IS FOR ALL ORDINARY PUBLIC SCHOOLS NOT PRIVATE SCHOOLS) MORE INFORMATION RE ADMISSION POLICY IS AVAILABLE ON THE SCHOOLS WEBSITE CLAREMONT HIGH SCHOOL R 8 700,00 OPEN DAY 5 & 6 FEB 021-6710645 15:15 - 16:30 MOLTENO ROAD CLOSING DATE 11 MARCH CLAREMONT www.claremonthigh.co.za APPLICATIONS ON WEBSITE GARDENS COMMERCIAL R 8 600,00 APPLICATION OPEN 4 FEB 021-4651236 CLOSING DATE 31 MARCH PADDOCK AVENUE GARDENS www.gardenshigh.co.za ON-LINE APPLICATIONS ONLY GARLANDALE SECONDARY R 2 000,00 APPLICATION OPEN 15 FEB 021-6967908 CLOSING DATE MARCH GENERAL STREET, ATHLONE GROENVLEI SECONDARY R 2 500,00 APPLICATION OPEN 15 FEB 021-7032227 CLOSING DATE 15 MARCH c/o BAREND ST & ST JOSEPHS RD, LANSDOWNE GROOTE SCHUUR HIGH SCHOOL R 26 450,00 APPLICATION OPEN 12 FEB 021-6742165 CLOSING DATE 23 MARCH PALMYRA ROAD DETAILS ON THE WEBSITE NEWLANDS www.grooteschuurhigh.co.za ISLAMIA SECONDARY R 37 500,00 APPLICATIONS AVAILABLE NOW 021-6965600 CLOSES END OF MARCH 409 IMAM HARON ROAD LANSDOWNE www.islamiacollege.co.za -

High School Deadline

HIGH SCHOOLS FOR GRADE 7'S HIGH SCHOOL FEES P/A DEADLINE CEDAR HOUSE SCHOOL R 73 120.00 021-7620649 APPLICATIONS ARE NOW OPEN 5 ASCOT ROAD, KENILWORTH www.cedarhouse.co.za CLAREMONT HIGH SCHOOL R 5 500.00 OPEN DAY 25 & 26 FEB 021-6710645 15:15 - 16:30 MOLTENO ROAD CLOSING DATE 22 APRIL CLAREMONT www.claremonthigh.co.za GARDENS COMMERCIAL R 7 250.00 APPLICATIONS OPEN IN 021-4651236 FEBRUARY PADDOCK AVENUE CLOSING DATE 25 MARCH GARDENS www.garcom.co.za GARLANDALE SECONDARY R 1 600.00 APPLICATION OPEN 021-6967908 EARLY MARCH CLOSE IN JUNE GENERAL STREET, ATHLONE GROENVLEI SECONDARY R 1 500.00 OPEN EARLY FEB 021-7032227 AND CLOSE END OF JULY c/o BAREND ST & ST JOSEPHS RD, LANSDOWNE GROOTE SCHUUR HIGH SCHOOL R 18 850.00 DETAILS WILL BE POSTED 021-6742165 ON THE WEBSITE PALMYRA ROAD END OF FEBRUARY NEWLANDS www.grooteschuurhigh.co.za HERITAGE COLLEGE R 43 200.00 APPLICATIONS OPEN FEBRUARY 021-6718153 225 LANSDOWNE ROAD CLAREMONT www.heritagecollege.co.za ISLAMIA SECONDARY R 28 150.00 LIMITED SPACE LEFT 021-6965600 409 LANSDOWNE ROAD LANSDOWNE www.islamiacollege.co.za LIVINGSTONE HIGH SCHOOL R 6 100.00 APPLICATIONS READY 021-6715986 CLOSING MID MARCH LANSDOWNE ROAD CLAREMONT www.livingstonehigh.co.za 1 2015/02/04 HIGH SCHOOLS FOR GRADE 7'S NORMAN HENSHILWOOD HIGH SCHOOL R 15 500.00 CLOSING DATE 021-7978043 20 MARCH CONSTANTIA ROAD, CONSTANTIA www.nhhs.co.za OAKLANDS HIGH SCHOOL R 1 400.00 OPEN MARCH CLOSES SEPTEMBER 021-7617302 CHUKKER ROAD, LANSDOWNE OUDE MOLEN TECHNICAL COLLEGE R 11 990.00 OPEN DAY 021-5312108 7TH MARCH 09:00 - 13:00 JAN SMUTS -

Heritage Statement

HERITAGE STATEMENT ERF 177552 MILL STREET NEWLANDS CAPE TOWN APPLICATION TO DEMOLISH EXISTING BUILDING SUBMITTED TO HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE IN TERMS OF NATIONAL HERITAGE RESOURCES ACT NO 25 OF 1999 SECTION 34 View of site from Campground Bridge building indicated with red arrow, Google Earth 2015 Prepared for Eris Property Group 10th Floor 80 Strand Street Cape Town 8001 E-mail: [email protected] Tel +27 21 410 1160 Fax +27 21 418 2249 PostNet Suite 122 Private Bag X1005 Claremont 7735 Cape Town South Africa Mobile: 0711090900 Fax: 086 511 0389 E-Mail: [email protected] HERITAGE STATEMENT ERF 177552 MILL STREET NEWLANDS CAPE TOWN FINAL 17 JULY 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.1 INTRODUCTION 3 1.2 LEGAL REQUIREMENTS 3 1.3 THE SITE 3 1.4 REPORT SCOPE OF WORK 3 1.5 ASSUMPTIONS AND LIMITATIONS 3 1.5.1 ASSUMPTIONS 3 1.5.2 LIMITATIONS 3 1.6 SPECIALIST TEAM AND DETAILS 3 1.7 DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 3 1.8 REPORT STRUCTURE 4 SECTION 2 STATUTORY FRAMEWORK 5 2.1 INTRODUCTION 5 2.2 ADMINISTRATIVE CONTEXT AND STATUTORY FRAMEWORK 5 2.2.1 INTRODUCTION 5 2.2.2 NATIONAL HERITAGE RESOURCES ACT NO. 25 OF 1999 (NHR ACT) 5 2.2.3 MUNICIPAL POLICY AND PLANNING CONTEXT 6 SECTION 3 DESCRIPTION OF THE SITE AND CONTEXT 9 3.1 NEWLANDS DEVELOPMENT 9 3.2 CONTEXTUAL ASSESSMENT OF SITE 11 3.3 DEVELOPMENT OF SITE 12 3.4 CONTEXT 16 3.5 SITE 18 SECTION 4 SITE & CONTEXT IDENTIFIED HERITAGE RESOURCES & STATEMENT OF HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCES 20 4.1 INTRODUCTION 20 4.2 SITE AND CONTEXT: PROVISIONAL STATEMENT OF CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE 20 SECTION 5 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 22 5.1 CONCLUSION 22 5.2 RECOMMENDATIONS 22 5.3 SOURCES 22 BRIDGET O’DONOGHUE ARCHITECT, HERITAGE SPECIALIST ENVIRONMENT 2 SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION Tommy Brummer Town Planners on behalf of their client, Eris Property Group appointed Bridget O’Donoghue Architect, Heritage Specialist, Environment for a Heritage Statement for the proposed demolition of the existing building situated on Erf 177552 Newlands Cape Town. -

Telling Stories to a Different Beat: Photojournalism As a “Way of Life”

Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Busst, Naomi Award date: 2012 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Naomi Verity Busst, BPhoto, MJ A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Media and Communication Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Bond University February 2012 Abstract This thesis presents a grounded theory of how photojournalism is a way of life. Some photojournalists dedicate themselves to telling other people's stories, documenting history and finding alternative ways to disseminate their work to audiences. Many self-fund their projects, not just for the love of the tradition, but also because they feel a sense of responsibility to tell stories that are at times outside the mainstream media’s focus. Some do this through necessity. While most photojournalism research has focused on photographers who are employed by media organisations, little, if any, has been undertaken concerning photojournalists who are freelancers. -

Missed Experience and South African Documentary Photography

REDISCOVERING THE (EXTRA)ORDINARY: MISSED EXPERIENCE AND SOUTH AFRICAN DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY ANDRÉ WIESNER 30 - Abstract Under apartheid, activist and commercial photog- André Wiesner is lecturer raphers confronted violent, traumatic events, and their in the Centre for Film and exposure of these to the wider world played a key role in Media Studies, University of bringing about the downfall of the state. Post-apartheid, Cape Town; e-mail: documentary photography has generally taken a diff erent [email protected]. direction, orienting attention to the surrounding society, and making good on all manner of missed experiences. In their move to peripheral situations, photographers dignify the culture-making of ordinary folk. The persons in the photographer’s gaze are frequently those caught in the shock waves of hostilities (Guy Tillim), affl icted by a dread epidemic (Kim Lubdrook), or exposed to a diff use 7 3, pp. (2007), No. Vol.14 condition of endangerment, like violent criminality (David Southwood). Photographers are themselves in a way fatally endangered from afar and their attempts to visualise what is out of frame can be seen as a form of self-defence and passionate search in a bid to come to terms with trouble. The essay probes the post-apartheid state of documentary photography and its current directions. 7 The Great Traditions In the year 2000 a young photographer called David Southwood held an exhibi- tion that to some would have looked rott en with fi n de siècle decadence. It featured an assortment of men and women in whom fl ickers of Southwood’s manner and morphology could be glimpsed, and was entitled, “People Who Other People Think Look Like Me.” Coming ten years aft er Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, and six years aft er South Africa’s landmark elections in 1994, the exhibition could be taken to epitomise the liberated, post-political sensibilities that fl ourished as the country shed its pariah status in the world at large and self-congratulatingly be- gan reinventing itself as a new and improved Rainbow Nation. -

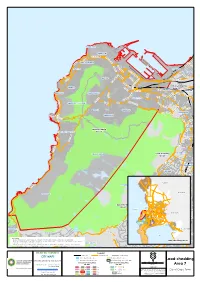

Load-Shedding Area 7

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

Elusive Equity : Education Reform in Post-Apartheid South Africa / Edward B

������������������������������������������������ ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p � � � �� �� �� ��� � Free download from www.hsrc ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p Free download from www.hsrc Elusive Equity Title.pdf 4/6/2005 4:10:21 PM ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p C M Y Education reform in CM post-apartheid South Africa MY CY CMY K Free download from www.hsrc Edward B Fiske & Helen F Ladd ABOUT BROOKINGS The Brookings Institution is a private nonprofit organization devoted to research, educa- tion, and publication on important issues of domestic and foreign policy. Its principal pur- pose is to bring knowledge to bear on current and emerging policy problems. The Institu- tion maintains a position of neutrality on issues of public policy. Interpretations or conclusions in Brookings publications should be understood to be solely those of the authors. Copyright © 2004 Edward B. Fiske and Helen F. Ladd ress.ac.za ress.ac.za p All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Brookings Institution Press, 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 (fax: 202/797-6195 or e- mail: [email protected]). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Fiske, Edward B. Elusive equity : education reform in post-apartheid South Africa / Edward B. Fiske and Helen F. Ladd. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8157-2840-9 (cloth : alk. paper) Free download from www.hsrc 1. Educational equalization—South Africa. 2. Education and state—South Africa. 3. -

AK2117-J2-3-C102-001-Jpeg.Pdf

^m - fc V , m ■*. V C 0 JSITENTJ 5 Note: This booklet 1n It s present form 1s not complete but ha< hAnn SS*El?,e t0 y0U “ th,S P01"‘ 1" 1. Declaration of the United Democratic Front 2. UDF National Executive Coimrittee 3. UDF Regional Executive Committees 4. Statement of the UDF National General Council 5. Secretarial Report 6. Working Principles 7. Resolutions: Detentions and Treason Trial Banning of the UDF and A ffiliates in the Bantustans UDF International Relations Trade Unions- - — * — . Unemployment Forced Removals Rural Areas Militarisation (• Women ' Black Local Authorities Tricameral Parliament and Black Forum ) - Citizenship Imperialism Imperialism USA International Year of the Youth Education Namibia * New Zealand Rugby Tour 3 Declaration of the United Democratic Front We. the freedom loving people of South Africa, say with one voice to tbe whole worio that we • cherish the vision o f a united. demooaU . South A fno based on the wa of the people. • wa strive for the unity of a l people am «h united • the cpprKs^andesploitation °f w om en w a con- > onue. Women wil suffer greater rurdshcn under me acfonagamsttheevasof apartheid, econaac and al mw other forms of e«*xoOon ^ WomefV wtf be (Evicted from their ctwW* fen md fjmftes. P iw iy snd malnutrition wfli continue Ana. In our march to a free and Job South Africa, we are guided by these noble £ S J S t ^ ti & bnn'* *wh6fl**'■** Ideals *Sr Potion of a true deecracv In which a i South Africans W participate h a t govern- ment of our councrr. -

Tribeca Film in Partnership with American Express and Entertainment 1 Present

Tribeca Film in Partnership with American Express and Entertainment 1 Present Release: April 22, 2011 – NY/LA/Chicago/Irvine April 29, 2011 – Washington DC/Seattle/Santa Monica May 6, 2011 – Landsdowne, PA/Monterey, CA/Long Beach, CA May 13, 2011 – San Diego May 20, 2011 – Palm Desert, CA With additional marKets TBC VOD - April 20 – June 23 PRESS CONTACT Distributor: Publicity: Tribeca Film ID PR Tammie Rosen Dani Weinstein 212-941-2003 Sara Serlen [email protected] Sheri Goldberg 375 Greenwich Street 212-334-0333 New York, NY 10011 [email protected] 150 West 30th Street, 19th Floor New York, NY 10001 1 SYNOPSIS The Bang Bang Club is the real life story of a group of four young combat photographers - Greg Marinovich, Joao Silva, Kevin Carter and Ken Oosterbroek - bonded by friendship and their sense of purpose to tell the truth. They risked their lives and used their camera lenses to tell the world of the brutality and violence associated with the first free elections in post Apartheid South Africa in the early 90s. This intense political period brought out their best work – two won Pulitzers during the period – but cost them a heavy price. Based on the book of the same name by Marinovich and Silva, the film stars Ryan Phillipe, Malin Akerman and Taylor Kitsch and explores the thrill, danger and moral questions associated with exposing the truth. 2 ABOUT THE DIRECTOR Written and directed by Steven Silver, The Bang Bang Club is a Canada/South Africa co-production from producer Daniel Iron of Foundry Films Inc. -

Award Winners

1 AWARD WINNERS The annual University of Cape Town Mathematics Competition took place on the UCT campus on 14 April this year, attracting over 6600 participants from Western Cape high schools. Each school could enter up to five individuals and five pairs, in each grade (8 to 12). The question papers were set by a team of local teachers and staff of the UCT Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics. Each paper consisted of 30 questions, ranging from rather easy to quite difficult. Gold Awards were awarded to the top ten individuals and top three pairs in each grade. Grade 8: Individuals 1 Soo-Min Lee Bishops 2 Tae Jun Rondebosch Boys' High School 3 Christian Cotchobos Bishops 4 Sam Jeffery Bishops 5 Mark Doyle Parel Vallei High School 5 David Meihuizen Bridge House 7 David Kube S A College High School 8 Christopher Hooper Rondebosch Boys' High School 9 Phillip Marais Bridge House 10 Alec de Wet Paarl Boys' High School Grade 8: Pairs 1 Liam Cook / Julian Dean-Brown Bishops 2 Alexandra Beaven / Sara Shaboodien Herschel High School 3 Albert Knipe / Simeon van den Berg Ho¨erskool D F Malan 3 Glenn Mamacos / James Robertson Westerford High School Grade 9: Individuals 1 Daniel Mesham Bishops 1 Robin Visser St George's Grammar School 3 Warren Black Bishops 3 Adam Herman Rondebosch Boys' High School 3 Murray McKechnie Bishops 6 Michelle van der Merwe Herschel High School 7 Philip van Biljon Bishops 8 Ryan Broodryk Westerford High School Award Winners 2 Grade 9: Individuals (cont'd) 9 Jandr´edu Toit Ho¨erskool De Kuilen 9 Christopher Kim Reddam -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL