Urban Redevelopment, Governance and Vulnerability: Thirty Years of ‘Regeneration’ in Dublin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Spencer Dock

ARGUABLY THE MOST PROMINENT OFFICE BUILDING IN A LOCATION SYNONYMOUS WATCH THE VIDEO WITH ICONIC DUBLIN LANDMARKS, GLOBAL LEADERS AND A THRIVING LOCAL ECONOMY IRELAND’S LARGEST OFFICE INVESTMENT 2 3 THE HEADLINES FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY ON THE INSTRUCTION OF: The Joint Receiver, REAL ESTATE Luke Charleton & David Hughes of EY Investment & Management • Grade A office building extending to approximately 21,054 sq m (226,624 sq ft) • 100 basement car parking spaces • Let to PwC, the largest professional services firm in Ireland • Long unexpired lease term, in excess of 16.5 years • Passing rent of €11,779,241 per annum • Strong reversionary potential (current passing rent of approximately €50 per sq ft) • Upward only rent reviews (next review April 2017) • Tenant unaffected by the sale www.onespencerdock.com 4 5 A PRIME WATERFRONT LOCATION 6 7 DOCKLANDS TRAIN STATION 3 GARDINER STREET 5 9 CONNOLLY BUS ROUTE MARLBOROUGH TALBOT STREET BUSARAS AMIENS STREET 4 2 MAYOR SQUARE 1 O’CONNELL GPO O’CONNELL STREET IFSC SPENCER DOCK POINT VILLAGE ABBEY STREET NORTH DOCKS CUSTOM HOUSE QUAY DUBLIN BIKES PROPOSED DOCKLANDS DUBLIN BIKES RAPID TRANSIT QUALITY DUBLIN BIKES NORTH WALL QUAY BUS CORRIDOR DUBLIN BIKES BUS ROUTE DUBLIN BIKES DUBLIN BIKES RIVER LIFFEY SAMUEL DUBLIN BIKES BECKETT 6 CITY QUAY TARA STREET DUBLIN BIKES BRIDGE PROPOSED LINK D’OLIER STREET BRIDGE SIR JOHN ROGERSONS QUAY WESTMORELAND MOSS STREET DUBLIN BIKES SOUTH TRINITY DUBLIN BIKES DUBLIN BIKES DOCKS PEARSE STREET TARA STREET DUBLIN BIKES GRAND CANAL DUBLIN BIKES HANOVER QUAY SQUARE -

1 Actually-Existing Smart Dublin

Actually-existing Smart Dublin: Exploring smart city development in history and context Claudio Coletta, Liam Heaphy and Rob Kitchin Pre-print of a chapter appearing in: Coletta, C., Heaphy, L. and Kitchin, R. (2018) Actually-existing Smart Dublin: Exploring smart city development in history and context. In Karvonen, A., Cugurullo, F. and Caprotti, F. (eds) In- side Smart Cities: Place, Politics and Urban Innovation. Routledge. pp. 85-101. Abstract How does the ‘smart city’ manifest itself in practice? Our research aims to separate substance from spin in our analysis of the actually-existing smart city in Dublin, Ireland. We detail how the smart city has been brought into common discourse in the Dublin city region through the Smart Dublin initiative, examining how the erstwhile ‘accidental smart city’ until 2014 has been rearticulated into a new vision for Dublin. The chapter is divided into two parts. In the first part we map out the evolution of smart urbanism in Dublin by tracing its origins back to the adoption of neoliberal policies and practices and the rolling out of entrepreneurial urbanism in the late 1980s. In the second part, we detail the work of Smart Dublin and the three principle components of current smart city-branded activity in the city: an open data platform and big data analytics; the rebranding of autonomous technology-led systems and initiatives as smart city initiatives; supporting innovation and inward investment through testbedding and smart districts; and adopting new forms of procurement designed to meet city challenges. In doing so, we account for the relatively weak forms of civic participation in Dublin’s smart city endeavours to date. -

Tall Buildings in Dublin

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The Need for Vision: Tall Buildings in Dublin Author: Brian Duffy, Associate, Traynor O'Toole Architects Subject: Urban Design Keywords: Development Master Planning Urban Sprawl Vertical Urbanism Publication Date: 2008 Original Publication: CTBUH 2008 8th World Congress, Dubai Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Brian Duffy The Need for Vision: Tall Buildings in Dublin Brian Duffy Associate, Traynor O’Toole Architects – 49 Upper Mount Street, Dublin 2, Ireland Abstract The Celtic Tiger economy in Ireland has dramatically changed the substance of life in Ireland within a very short space of time. Whilst the infrastructure has struggled to keep up, the urban realm has begun the process of rapidly transforming Dublin from a low rise city of urban sprawl, to a densely woven contemporary modern environment. The appetite to build tall is tempered by an apprehensive planning policy, that reflects the cautious mood of the general public. Such apprehension restricts the possibility of creating an of-its-time City that meets it demands sustainably, whilst fulfilling its high aspirations. The paper examines planning policies and how Dublin architects have pursued tall buildings, most typically in the city centre. This is then contrasted with an alternative approach on the edge of the city, where one major landowner and [email protected] design team have proposed an entire masterplanning vision, premised on the inclusion of tall buildings. This untypical approach yields notable success and, in doing so, highlights the need for a more proactive and interactive approach to Biography Briantall building Duffy qualifiedstrategic planningfrom Queens on behalf University of architects, Belfast, developers Northern Ireland, and planners before alike. -

Mission Statement We Will Develop Dublin Docklands Into a World-Class

Presentation to Delegation from Stockholm 25th April, 2007 Paul Maloney, CEO 1. THE DOCKLANDS PROJECT BACK IN 1987 • Population at 16,000 • Dereliction • Economic deprivation • Educational disadvantage 1. THE DOCKLANDS PROJECT CUSTOM HOUSE DOCKS / IFSC 1997 22.0 hectares 1. THE DOCKLANDS PROJECT STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES Accelerating physical rollout Achieving architectural legacy Fulfilling the potential of the Docklands Realising quality of life Creating a sense of place Physical Development…. 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT DOCKLANDS NORTH LOTTS Commercial Space Completed 17,288m2 2002 Permitted 62,402m2 Housing units 2007 Completed 343 Permitted 1,606 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT GRAND CANAL DOCK Commercial Space 2 2002 Completed 55,412m Permitted 184,018m2 Housing units 2007 Completed 910 Permitted 1,516 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT NEW TENANTS MOVING INTO DOCKLANDS ESRI Dillon Eustace O2 Mason Hayes Curran PWC Mason Hayes Curran McCann Fitzgerald Google Beauchamps Fortis Bank Google PFPC Irish Taxation Institute Anglo Irish Bank MOPS O’Donnell Sweeney Arups U2 Tower Arups 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT POINT VILLAGE Point Village 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT PLANNING IN NORTH LOTTS Proposed new Masterplan 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT POOLBEG PENINSULA New City Quarter • Over 100 acres • Public transport infrastructure • Urban sustainable development • Amenities, cultural & community interventions Review of Heights and Densities 2. PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT STREETSCAPES Price Waterhouse Coopers McCann Fitzgerald Forbe’s Quay Google Architectural Legacy… 3. Architectural Legacy Dublin’s Architectural Gateway U2 Tower The WatchTower 3. Architectural Legacy SAMUEL BECKETT BRIDGE 3. Architectural Legacy NATIONAL CONFERENCE CENTRE AT SPENCER DOCK 3. Architectural Legacy chq - CONSERVATION 3. Architectural Legacy ROYAL CANAL LINEAR PARK 3. Architectural Legacy GRAND CANAL SQUARE/LIBESKIND THEATRE Realising Quality of Life… 4. -

Economy and Authority: a Study of the Coinage of Hiberno-Scandinavian Dublin and Ireland

Economy and Authority: A study of the coinage of Hiberno-Scandinavian Dublin and Ireland Volume 1: Text Andrew R. Woods Peterhouse This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Division of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge 2013 1 This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. The following does not exceed the word limit (80,000 words) set out by the Division of Archaeology and Anthropology degree committee. 2 Abstract Economy and Authority: A study of the coinage of Hiberno-Scandinavian Dublin and Ireland Andrew R. Woods The aim of this thesis is to investigate the relationship between political authority and economic change in the tenth to twelfth centuries AD. This is often interpreted as a period of dramatic economic and political upheaval; enormous growth in commerce, the emergence of an urban network and increasingly centralised polities are all indicative of this process. Ireland has rarely been considered in discussion of this sort but analysis of Ireland’s political economy has much to contribute to the debate. This will be tackled through a consideration of the coinage struck in Ireland between c.995 and 1170 with focus upon the two themes of production and usage. In analysing this material the scale and scope of a monetary economy, the importance of commerce and the controlling aspects of royal authority will each be addressed. The approach deployed is also overtly comparative with material from other contemporary areas, particularly England and Norway, used to provide context. -

Eastside Docklands - Construction and Unemployment Changing the Narrative

2020 Construction and Unemployment Changing the Dublin Narrative Eastside + Docklands Local Employment Services A project of St. Andrew’s Resource Centre + Inner City Renewal Group Report on Dublin City Construction Skills Project 2020 Eastside Docklands - Construction and Unemployment Changing the Narrative Employment and Unemployment Trends in Ireland and Impact on Young Workers Increase in Since 2017 Ireland has continued to experience The scale of youth unemployment, and proportion of long- a strengthening labour market, with further its potential for long-term damage to the term unemployed improvements in the number of labour market employment prospects of individuals, highlights indicators. In 2017, the unemployment level the need for policies to actively address youth 2007 declined by 37,000, while the unemployment and young people unemployed. This report rate declined by 1.7% to an annual average deals with the impact on a specified area and of 6.7%. client cohorts. As the thinking about how best 27% to address the issue the youth and Long term The unemployment rate in Ireland is still higher unemployment rates in specific communities than in the period from 2002-2007.1 In Ireland were considered. by 2018, there were 36,000 more people unemployed (and 23,000 more long-term unemployed), than there had been in 2005, with evidence that the employment rate is still far Long Term Unemployed from recovering from the impact of the financial As the development of the project continued 2010 crisis. As is noted by Ciarán Nugent of NERI, this the figures were stark. While the wider lack of recovery in the unemployment figures unemployment rate has declined by 1.7%, it is is due, for the most part, to the collapse of of note that the rate for long term unemployed employment for younger cohorts, particularly declined by only 0.8% to 2.5% in quarter 4 for young men. -

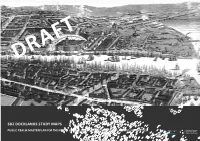

Sdz Docklands Study Maps

1 DRAFT SDZ DOCKLANDS STUDY MAPS PUBLIC REALM MASTERPLAN FOR THE NORTH LOTTS & GRAND CANAL DOCK SDZ PLANNING SCHEME 2014 2 Public Realm Masterplan North Lotts & Grand Canal Dock Dublin City Council working group Deirdre Scully (planner) Jeremy Wales (architect) Jason Frehill (planner) Seamus Storan (engineer) Peter Leonard (parks) REDscape Landscape & Urbanism with Howley Hayes, Scott Cawley, Build Cost, O Connor Sutton Team REDscape Landscape & Urbanism: Howley Hayes Architects (heritage) : Fergal Mc Namara. Patrick Mc Cabe, landscape architect Scott Cawley Ecologists: (ecology) Paul Scott. David Habets, landscape designer O Connor Sutton Cronin Engineers: (PSDP) Anthony Horan. Joanne Coughlan, landscape architect Build Cost Quantity Surveyors: Liam Langan. Antoine Fourrier, landscape designer Andreas Mulder, urban designer Cover image: Perspective of the liffey, North Lotts and Grand Canal Dock. Legal This report contains several images and graphics based on creative representations. No legal rights can be given to these representations. All images have been accredited. Where the source is not clear, all efforts have been made to clarify the source. Date: January 2016 Dublin City Council Prepared by REDscape Landscape & Urbanism. 77 Sir John Rogerson’s Quay, Dublin 2. www.redscape.ie 3 Content Parks, squares, play areas Public transport Pedestrian routes Bicycle Routes Car road hierarchy Transport connections Underground infrastructure Tree structure Cultural and community facilities Water activities and facilities Creative hubs Urban development North Lotts shadow study North Lotts underground infrastructure 4 Public Realm Masterplan public green spaces North Lotts & Grand Canal Dock square & plaza football ptich proposed public green spaces 8 - 20+ y/o proposed square & plaza playground open air sport Play Ground Mariners Port Station Square Middle Park 2 - 7 y/o Point Square Pocket Park Source : Comhairle Cathrach Bhaile Átha Cliath - Dublin City Council, Maps & Figures,North Lotts & Grand Canal Dock Planning Scheme, 5th November 2013, Fig. -

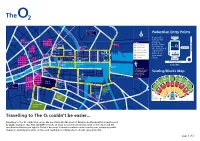

Travelling to the O2 Couldn't Be Easier

Colour palette Primary colour Pantone CMYK RGB Websafe Gardiner St Upper Port land Five Clontarf Road ll Row hi Lamps Ea r Dart Station s Pedestrian Entry Points t W ROY 1km / 14min walk all Rd l Summe A L unne CANAL T rt Please take B t o S P per 20 27 116 145 note of the Up Parnel B A B A PMS 2747 C100 M094 Y000 K029 R000 G000 B102 Hex 000066 27C 29 31 31 32B Seville Plac B Gardiner St 40 40 120 123 A A Amiens East Rd LEGEND entrance l Sq East 42 42B 43 51 53 St Connolly A points. These Secondary colours 53 53 142 ll Rd Dorset St 90 127 129 130 142 e Rail / Dart Line A Station t Wall Rd 11 11 B s Parnell Docklands correlate to Lower Wa A Ea LUAS Red Line PMS 2768 C095 M081 Y000 K059 R025 G034 B079 Hex 000033 13 13 14 Station the designated A 93 151 O’Connell St 16 16 19 LUAS Sheriff St Upper LUAS Green Line Sheriff St Lwr East A A entry point 40C 48 123 PMS 2945 C100 M038 Y000 K015 R000 G088 B150 Hex 003399 Mayor Pedestrian Route Taxi Rank printed on 747748 Square Commons St The Guild St Bus Route Stop Busáras your event PMS 2925 C087 M023 Y000 K000 R000 G144 B208 Hex 3399CC 2 3 4 5 Spire Mayor St Lower 4 5 Car Park Parnell St A A chq Convention ticket. B A 7 7 8 10 10 A Castleforbes Rd D 7 B 7 8 53 PMS 2915 C060 M011 Y000 K000 R101 G180 B228 Hex 66CCFF D New Wapping St A Centre 14A 16 16 19 38 151 A A D A C North Wall Quay 38C 46B 46E 48 58 Quay 93 90 North Wall Quay North Wall Quay C Abbey St Lower House A Custom PMS 290 C016 M000 Y000 K000 R190 G217 B237 Hex * C Capel St 63 121 122 145 746 38 38 Sean O’Casey Samuel Beckett 151 Foot-Bridge -

CROSS-BORDER ECONOMIC RENEWAL Rethinking Regional Policy in Ireland

Antrim Derry Donegal Tyrone Down Fermanagh Armagh Sligo Monaghan Leitrim The Centre for Cross Border Studies Cavan 39 Abbey Street, Armagh BT61 7EB Louth Northern Ireland Tel: +44 (0)28 3751 1550 Fax: +44 (0)28 3751 1721 (048 from the Republic of Ireland) Website: www.crossborder.ie CROSS-BORDER ECONOMIC RENEWAL Rethinking Regional Policy in Ireland John Bradley and Michael Best March 2012 This research project has received financial support from the EU INTERREG IVA Programme, managed by the Special EU Programmes Body CROSS-BORDER ECONOMIC RENEWAL Rethinking Regional Policy in Ireland John Bradley and Michael Best March 2012 1 Table of Acronyms NIEC Northern Ireland Economic Council NIERC Northern Ireland Economic Research Centre ABT An Bord Trachtala (Irish Trade Board) NUTS Nomenclature of Territorial Units for BAA British Airports Authority Statistics (EU) BDZ Border Development Zone OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation CAD/CAM Computer Aided Design/Manufacturing and Development CBI Confederation of British Industry ONS Office for National Statistics (UK) CCBS Centre for Cross Border Studies OP/ROP Operational Programme/Regional CEE Central and Eastern Europe Operational Programme (EU) CIP Census of Industrial Production OPEC Organization of the Petroleum Exporting CNC Computer Numerical Controlled (tool) Countries CSO Central Statistics Office (Ireland) PLC Product Life Cycle DETI Department of Enterprise, Trade and R&D Research and Development Investment (Northern Ireland) RCA Regional Competitiveness Agenda ECB European Central -

Docklands Going Wrong?

Docklands Going Wrong? Prof. Andrew MacLaran Department of Geography, Trinity College Dublin [email protected] Dr. Sinéad Kelly, Department of Geography, Maynooth University [email protected] Economic base • Declining industrial land uses, 1966-85 – Closures – Suburbanisation of manufacturing & warehousing Population & housing • Long-term pop. decline – 1911 pop 240,000 – 1979 pop 104,000 • Remaining population – Low level of skills – High unemployment – Small hh. & elderly • Poor housing (1974) – 40% lack bath – 25% blgs in poor condition – Poorly maintained local- authority dwellings 1985: 600 cleared sites & derelict buildings in the CBD itself (metered parking area) Combined area of 160 acres (65ha.) Derelict land & vacant buildings 1985 Docklands: on the eastern edge of the CBD Disused wet docks; derelict land; eyesore industries; scrap metal dealing; live animal exports; truck haulage yards; surface car parking etc. But did give some employment relevant to the low skills levels of local residents Pamplona ? Unemployment • Changing cargo-handling (pallets & containers) required only 10% of original labour force • Unemployment (mid 1980s) – Inner-city @ 35% – Sheriff Street @ 83% (social housing) Sheriff Street (social housing) Urban Renewal Act (1986) & Finance Act (1987) • Created a package of incentives aimed at encouraging development • Aims: – To stimulate private sector interest in inner-city renewal – To boost employment construction sector which had an unemployment rate of 45% • Strategic alliances forged between urban planners -

Provided by the Author(S) and University College Dublin Library in Accordance with Publisher Policies

Provided by the author(s) and University College Dublin Library in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Strategic economic policy : Milan, Dublin and Toulouse Authors(s) Mugnano, Silvia; Murphy, Enda; Martin-Brelot, Helene Publication date 2010 Publication information Musteard, S. and Murie, A. (eds.). Making competitive cities : real estate issues Publisher Wiley-Blackwell Item record/more information http://hdl.handle.net/10197/3017 Downloaded 2021-09-02T06:05:50Z The UCD community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters! (@ucd_oa) © Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Chapter 16: Strategic economic policy: Milan, Dublin and Toulouse Authors: Silvia Mugnano, Enda Murphy, Hélène Martin-Brelot Introduction This chapter compares three European cities with well-established and successful creative and/or knowledge based economies - Milan, Dublin and Toulouse1. However, each economy has different sectoral strengths and has different associated historical development paths and economic trajectories developed over varying time periods. As national capital of Ireland, Dublin possesses several conditions that are only partly present in the regional capitals of Lombardy and Midi-Pyrénées. Dublin‟s economic growth in both creative and knowledge sectors has been significant in the past two decades (Murphy and Redmond, 2009); Toulouse‟s development relies mainly on knowledge-based activities such as aeronautics, space and electronics; Milan‟s success in the creative industries occurred over a prolonged period of time. Over the centuries Milan has gained national primacy by becoming the financial, economic, innovative and creative capital of Italy. -

Line C Connolly to the Point Depot Chapter Page

Dublin Light Rail Environmental impact Statement Line C Connolly to The Point Depot Chapter Page 1: Introduction 3 2: Public Consultation 12 3: Consideration of Alternative Routes 21 4: Luas Red Line Extension: Project Description 34 5: Planning and Land Use Context 43 6: Socio Economic Context 53 7: Traffic and Transportation 62 8: Ecological Resources 85 9: Soil 90 10: Water 95 11: Noise and Vibration 99 12: Electromagnetic Effects 113 13: Air Quality and Climate 116 14: Landscape and Visual 126 15: Cultural Heritage 149 16: Impact Interactions 161 17: Statement of Assessment 167 Annex A: Landscape Insertion Plans 168 Annex B: RPA Consultation Newsletter 174 Annex C: Supporting Information on Climate and Air Quality 176 1 Availability of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) Copies of the EIS including the Non Technical Summary are available for inspection and pur- chase at the following locations: Railway Procurement Agency Parkgate Business Centre, Parkgate Street, Dublin 8. Dublin Transportation Office 69 – 71 St. Stephens Green, Hainault House, Dublin 2. The EIS is also available to download (free of charge) through the RPA website: www.rpa.ie Copies of this EIS can be purchased for a sum of ¤15.00 each; A CD version of the EIS can be purchased for a sum of ¤5.00; Photomontage showing proposed Luas Stop on Mayor Street Copies of the Non Technical Summary of this EIS may be purchased for a sum of ¤3.00 each at the above locations. 2 INTRODUCTION • to identify measures that should be taken to mit- sultants, ERM takes responsibility for the informa- igate potential adverse impacts; tion and recommendations contained in this EIS 1.1 OBJECTIVES OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT document.