Unit 6 India's Foreign Policy: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

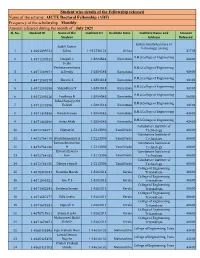

Student Wise Details of the Fellowship Released Name of the Scheme

Student wise details of the Fellowship released Name of the scheme: AICTE Doctoral Fellowship (ADF) Frequency of the scholarship –Monthly Amount released during the month of : July 2021 Sl. No. Student ID Name of the Institute ID Institute State Institute Name and Amount Student Address Released Indira Gandhi Institute of Sushil Kumar Technology, Sarang 1 1-4064399722 Sahoo 1-412736121 Orissa 31703 B.M.S.College of Engineering 2 1-4071237529 Deepak C 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Perla Venkatasreenivasu B.M.S.College of Engineering 3 1-4071249071 la Reddy 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 4 1-4071249170 Shruthi S 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 5 1-4071249196 Vidyadhara V 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 6 1-4071249216 Pruthvija B 1-5884543 Karnataka 86800 Tulasi Naga Jyothi B.M.S.College of Engineering 7 1-4071249296 Kolanti 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 8 1-4071448346 Manali Raman 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 B.M.S.College of Engineering 9 1-4071448396 Anisa Aftab 1-5884543 Karnataka 43400 Coimbatore Institute of 10 1-4072764071 Vijayan M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 11 1-4072764119 Sivasubramani P A 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Ramasubramanian Coimbatore Institute of 12 1-4072764136 M 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Eswara Eswara Coimbatore Institute of 13 1-4072764153 Rao 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 Coimbatore Institute of 14 1-4072764158 Dhivya Priya N 1-5213396 Tamil Nadu Technology 40600 -

Government of India Ministry of Culture Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No.2320 to Be Answered on 09.05.2016

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.2320 TO BE ANSWERED ON 09.05.2016 MEMORIALS IN THE NAME OF FORMER PRIME MINISTERS 2320. SHRI C.R. PATIL Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government makes the nomenclature of the memorials in name of former Prime Ministers and other politically, socially or culturally renowned persons and if so, the details thereof; (b) whether the State Government of Gujarat has requested the Ministry to pay Rs. One crore as compensation for acquiring Samadhi Land - Abhay Ghat to build a memorial in the name of Ex-PM Shri Morarji Desai and if so, the details thereof; (c) whether the Government had constituted a Committee in past to develop a memorial on his Samadhi; and (d) the action taken by the Government to acquire the Sabarmati Ashram Gaushala Trust land to make memorial in the name of the said former Prime Minister? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) FOR CULTURE & TOURISM AND MINISTER OF STATE FOR CIVIL AVIATION. DR. MAHESH SHARMA (a) Yes, Madam. The nomenclature of the memorials is given by the Government with the approval of Union Cabinet. For example: Samadhi of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru is known as Shanti Vana, Samadhi of Mahatama Gandhi is known as Rajghat, Samadhi of late Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri is known as Vijay Ghat, Samadhi of Ch. Charan Singh is known as Kisan Ghat, Samadhi of Babu Jagjivan Ram is known as Samta Sthal, Samadhi of late Smt. Indira Gandhi is known as Shakti Sthal, Samadhi of Devi Lal is known as Sangharsh Sthal, Samadhi of late Shri Rajiv Gandhi is known as Vir Bhumi and so on. -

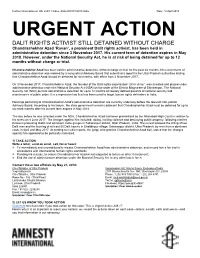

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture

Further information on UA: 248/17 Index: ASA 20/8191/2018 India Date: 10 April 2018 URGENT ACTION DALIT RIGHTS ACTIVIST STILL DETAINED WITHOUT CHARGE Chandrashekhar Azad ‘Ravan’, a prominent Dalit rights activist, has been held in administrative detention since 3 November 2017. His current term of detention expires in May 2018. However, under the National Security Act, he is at risk of being detained for up to 12 months without charge or trial. Chandrashekhar Azad has been held in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for the past six months. His current term of administrative detention was ordered by a non-judicial Advisory Board that submitted a report to the Uttar Pradesh authorities stating that Chandrashekhar Azad should be detained for six months, with effect from 2 November 2017. On 3 November 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, the founder of the Dalit rights organisation “Bhim Army”, was arrested and placed under administrative detention under the National Security Act (NSA) on the order of the District Magistrate of Saharanpur. The National Security Act (NSA) permits administrative detention for up to 12 months on loosely defined grounds of national security and maintenance of public order. It is a repressive law that has been used to target human rights defenders in India. Hearings pertaining to Chandrashekhar Azad’s administrative detention are currently underway before the relevant non-judicial Advisory Board. According to his lawyer, the state government remains adamant that Chandrashekhar Azad must be detained for up to six more months after his current term expires in May 2018. The day before he was arrested under the NSA, Chandrashekhar Azad had been granted bail by the Allahabad High Court in relation to his arrest on 8 June 2017. -

A Number of Decisions Made by the Rajiv Gandhi Government

Back to the Future: The Congress Party’s Upset Victory in India’s 14th General Elections Introduction The outcome of India’s 14th General Elections, held in four phases between April 20 and May 10, 2004, was a big surprise to most election-watchers. The incumbent center-right National Democratic Alliance (NDA) led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), had been expected to win comfortably--with some even speculating that the BJP could win a majority of the seats in parliament on its own. Instead, the NDA was soundly defeated by a center-left alliance led by the Indian National Congress or Congress Party. The Congress Party, which dominated Indian politics until the 1990s, had been written off by most observers but edged out the BJP to become the largest party in parliament for the first time since 1996.1 The result was not a complete surprise as opinion polls did show the tide turning against the NDA. While early polls forecast a landslide victory for the NDA, later ones suggested a narrow victory, and by the end, most exit polls predicted a “hung” parliament with both sides jockeying for support. As it turned out, the Congress-led alliance, which did not have a formal name, won 217 seats to the NDA’s 185, with the Congress itself winning 145 seats to the BJP’s 138. Although neither alliance won a majority in the 543-seat lower house of parliament (Lok Sabha) the Congress-led alliance was preferred by most of the remaining parties, especially the four-party communist-led Left Front, which won enough seats to guarantee a Congress government.2 Table 1: Summary of Results of 2004 General Elections in India. -

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions for Class 3

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions For Class 3 Answer the following GK Questions on 10 Prime Ministers of India: Q1. Name the first Prime Minister of India who served office (15 August 1947 - 27 May 1964) until his death. a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Jawaharlal Nehru c) Rajendra Prasad d) Lal Bahadur Shastri Q2. _____________________ is the current Prime Minister of India (26 May 2014 – present). a) Narendra Modi b) Atal Bihari Vajpayee c) Manmohan Singh d) Ram Nath Kovind Q3. Who was the Prime Minister of India (9 June 1964 - 11 January 1966) until his death? a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Charan Singh c) Lal Bahadur Shastri d) Morarji Desai Q4. Who served as Prime Minister of India from 24 January 1966 - 24 March 1977? a) Jawaharlal Nehru b) Gulzarilal Nanda c) Gopinath Bordoloi d) Indira Gandhi Q5. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 28 July 1979 - 14 January 1980. a) Jyoti Basu b) Morarji Desai c) Charan Singh d) V. V. Giri Q6. _______________________ served as the Prime Minister of India (21 April 1997 - 19 March 1998). a) Inder Kumar Gujral b) Charan Singh c) H. D. Deve Gowda d) Morarji Desai Q7. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 21 June 1991 - 16 May 1996. a) H. D. Deve Gowda b) P. V. Narasimha Rao c) Atal Bihari Vajpayee d) Chandra Shekhar Q8. ____________________________ was the Prime Minister of India (31 October 1984 - 2 December 1989). a) Chandra Shekhar b) Indira Gandhi c) Rajiv Gandhi d) P. V. Narasimha Rao Q9. -

Leader of the House F

LEADER OF THE HOUSE F. No. RS. 17/5/2005-R & L © RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI http://parliamentofindia.nic.in http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT PUBLISHED BY SECRETARY-GENERAL, RAJYA SABHA AND NEW DELHI PRINTED BY MANAGER, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI-110002. PREFACE This booklet is part of the Rajya Sabha Practice and Procedure Series which seeks to describe, in brief, the importance, duties and functions of the Leader of the House. The booklet is intended to serve as a handy guide for ready reference. The information contained in it is synoptic and not exhaustive. New Delhi DR. YOGENDRA NARAIN February, 2005 Secretary-General THE LEADER OF THE HOUSE Leader of the House in Rajya Sabha Importance of the Office Rule 2(1) of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Council of States (Rajya Sabha) defines There are quite a few functionaries in Parliament who the Leader of Rajya Sabha as follows: render members’ participation in debates more real, effective and meaningful. One of them is the 'Leader of "Leader of the Council" means the Prime Minister, the House'. The Leader of the House is an important if he is a member of the Council, or a Minister who parliamentary functionary who exercises direct influence is a member of the Council and is nominated by the on the course of parliamentary business. Prime Minister to function as the Leader of the Council. Origin of Office in England In Rajya Sabha, the following members have served In England, one of the members of the Government, as the Leaders of the House since 1952: who is primarily responsible to the Prime Minister for the arrangement of the government business in the Name Period House of Commons, is known as the Leader of the House. -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

BOOK REVIEW Hardeep Singh Puri,Delusional Politics, (New Delhi

Indian Foreign Affairs Journal Vol. 13, No. 4, October–December 2018, 345-357 BOOK REVIEW Hardeep Singh Puri, Delusional Politics, (New Delhi, Penguin Viking, 2019), Pages: 304, Price: Rs. 360.00 ‘Delusional Politics’ is an authoritative and insider account of the national and global impact of the rise of populism and an era of ‘alternative facts’ and ‘alternative narratives’ which exploits popular angst to capture political power. It is based on three case studies: the Brexit Referendum, the Trump Presidency, and the India Story. Its clinical analysis of delusional politics and decision making on global governance within the UN, based on the author’s personal experience of a wide range of multilateral negotiations, be it nuclear security, climate change, terrorism, and international trade, makes for fascinating reading. Historian, diplomat (with 40 years in the Foreign Service including as India’s Permanent Representative in Geneva and New York), and now Minister for Urban Affairs, the author explains how the globalisation narrative changed radically with the economic slowdown in the West, resulting on the one hand in the Trump Presidency and, on the other, in the disastrous Brexit referendum. The post-Westphalia, liberal democratic order, with its focus on individual rights and the scrutiny of the State changed sharply with the shrinking markets of the West and the rise of international terrorism. Both for Brexit and the Trump phenomenon, the assumption is clear: “We are in the dawn of a credibility crisis”. Data is distorted or manipulated to change a political narrative. It marks the rise of “post-truth politics” which for Brexit and Trump fed on the toxicity of a contrived and false narrative. -

Manmohan Singh 1

Manmohan Singh 1 As finance minister in Narasimha Rao's government of the '90s, Manmohan Singh helmed reforms that liberalized India's economy, changing it in a fundamental way. Singh discusses India's history of industrial policy and economic reform, the impact of globalization, and the role of government in the Indian economy. India's Central Planning: Nehru's Vision and the Reality INTERVIEWER: Nehru wrote that socialism has science and logic on its side. What did he mean by that? MANMOHAN SINGH: Nehru was a rational thinker, and he wanted to apply science and technologies to solve the living problems of our time. In India, the foremost problem was India's economic [and] social backwardness [and] the great mass poverty that prevailed at the time of independence. Nehru's vision was to get rid of that chronic poverty, ignorance, and disease, making use of modern science and technology. INTERVIEWER: The central aim was to modernize, industrializing in one generation. Was that a crazy idea or a good idea? MANMOHAN SINGH: Elsewhere in the world, there are instances [of this happening]. The Soviet Union industrialized itself with a single generation. The industrial revolution in England you can break down into phases. A lot of structural changes took place in one generation, which later on became irreversible. That was Nehru's vision. His vision was to industrialize India, to urbanize India, and in the process he hoped that we would create a new society—more rational, more humane, less ridden by caste and religious sentiments. That was the grand vision that Nehru had. -

RTI Handbook

PREFACE The Right to Information Act 2005 is a historic legislation in the annals of democracy in India. One of the major objective of this Act is to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority by enabling citizens to access information held by or under the control of public authorities. In pursuance of this Act, the RTI Cell of National Archives of India had brought out the first version of the Handbook in 2006 with a view to provide information about the National Archives of India on the basis of the guidelines issued by DOPT. The revised version of the handbook comprehensively explains the legal provisions and functioning of National Archives of India. I feel happy to present before you the revised and updated version of the handbook as done very meticulously by the RTI Cell. I am thankful to Dr.Meena Gautam, Deputy Director of Archives & Central Public Information Officer and S/Shri Ashok Kaushik, Archivist and Shri Uday Shankar, Assistant Archivist of RTI Cell for assisting in updating the present edition. I trust this updated publication will familiarize the public with the mandate, structure and functioning of the NAI. LOV VERMA JOINT SECRETARY & DGA Dated: 2008 Place: New Delhi Table of Contents S.No. Particulars Page No. ============================================================= 1 . Introduction 1-3 2. Particulars of Organization, Functions & Duties 4-11 3. Powers and Duties of Officers and Employees 12-21 4. Rules, Regulations, Instructions, 22-27 Manual and Records for discharging Functions 5. Particulars of any arrangement that exist for 28-29 consultation with or representation by the members of the Public in relation to the formulation of its policy or implementation thereof 6. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXIV NO.1 MARCH 2018 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.1 MARCH 2018 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION _____________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.1 MARCH 2018 _____________________________________________________________ CONTENTS PAGE ADDRESS - Address by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Smt. Sumitra Mahajan at the 137th Assembly of IPU at St. Petersburg, Russian Federation -- - Address by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Smt. Sumitra Mahajan at the 63rd Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference, Dhaka, Bangladesh -- PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES -- PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS -- PRIVILEGE ISSUES -- PROCEDURAL MATTERS -- DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST -- SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha -- Rajya Sabha -- State Legislatures -- RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST -- APPENDICES -- I. Statement showing the work transacted during the … Thirteenth Session of the Sixteenth Lok Sabha II. Statement showing the work transacted during the … 244th Session of the Rajya Sabha III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of … the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2017 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament … and assented to by the President during the period 1 October to 31 December 2017 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States … and the Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2017 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union … and State Governments during the period 1 October to 31 December 2017 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, the Rajya Sabha … and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories ADDRESS OF THE SPEAKER, LOK SABHA, SMT. SUMITRA MAHAJAN AT THE 137TH ASSEMBLY OF THE INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION (IPU), HELD IN ST. -

India's Nuclear Odyssey

India’s Nuclear Odyssey India’s Nuclear Andrew B. Kennedy Odyssey Implicit Umbrellas, Diplomatic Disappointments, and the Bomb India’s search for secu- rity in the nuclear age is a complex story, rivaling Odysseus’s fabled journey in its myriad misadventures and breakthroughs. Little wonder, then, that it has received so much scholarly attention. In the 1970s and 1980s, scholars focused on the development of India’s nuclear “option” and asked whether New Delhi would ever seek to exercise it.1 After 1990, attention turned to India’s emerg- ing, but still hidden, nuclear arsenal.2 Since 1998, India’s decision to become an overt nuclear power has ushered in a new wave of scholarship on India’s nu- clear history and its dramatic breakthrough.3 In addition, scholars now ask whether India’s and Pakistan’s acquisition of nuclear weapons has stabilized or destabilized South Asia.4 Despite all the attention, it remains difªcult to explain why India merely Andrew B. Kennedy is Lecturer in Policy and Governance at the Crawford School of Economics and Gov- ernment at the Australian National University. He is the author of The International Ambitions of Mao and Nehru: National Efªcacy Beliefs and the Making of Foreign Policy, which is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. The author gratefully acknowledges comments and criticism on earlier versions of this article from Sumit Ganguly, Alexander Liebman, Tanvi Madan, Vipin Narang, Srinath Raghavan, and the anonymous reviewers for International Security. He also wishes to thank all of the Indian ofªcials who agreed to be interviewed for this article.