Chapter Preview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

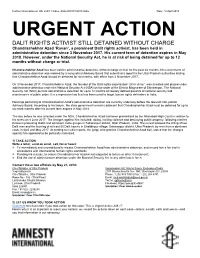

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture

Further information on UA: 248/17 Index: ASA 20/8191/2018 India Date: 10 April 2018 URGENT ACTION DALIT RIGHTS ACTIVIST STILL DETAINED WITHOUT CHARGE Chandrashekhar Azad ‘Ravan’, a prominent Dalit rights activist, has been held in administrative detention since 3 November 2017. His current term of detention expires in May 2018. However, under the National Security Act, he is at risk of being detained for up to 12 months without charge or trial. Chandrashekhar Azad has been held in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for the past six months. His current term of administrative detention was ordered by a non-judicial Advisory Board that submitted a report to the Uttar Pradesh authorities stating that Chandrashekhar Azad should be detained for six months, with effect from 2 November 2017. On 3 November 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, the founder of the Dalit rights organisation “Bhim Army”, was arrested and placed under administrative detention under the National Security Act (NSA) on the order of the District Magistrate of Saharanpur. The National Security Act (NSA) permits administrative detention for up to 12 months on loosely defined grounds of national security and maintenance of public order. It is a repressive law that has been used to target human rights defenders in India. Hearings pertaining to Chandrashekhar Azad’s administrative detention are currently underway before the relevant non-judicial Advisory Board. According to his lawyer, the state government remains adamant that Chandrashekhar Azad must be detained for up to six more months after his current term expires in May 2018. The day before he was arrested under the NSA, Chandrashekhar Azad had been granted bail by the Allahabad High Court in relation to his arrest on 8 June 2017. -

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions for Class 3

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions For Class 3 Answer the following GK Questions on 10 Prime Ministers of India: Q1. Name the first Prime Minister of India who served office (15 August 1947 - 27 May 1964) until his death. a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Jawaharlal Nehru c) Rajendra Prasad d) Lal Bahadur Shastri Q2. _____________________ is the current Prime Minister of India (26 May 2014 – present). a) Narendra Modi b) Atal Bihari Vajpayee c) Manmohan Singh d) Ram Nath Kovind Q3. Who was the Prime Minister of India (9 June 1964 - 11 January 1966) until his death? a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Charan Singh c) Lal Bahadur Shastri d) Morarji Desai Q4. Who served as Prime Minister of India from 24 January 1966 - 24 March 1977? a) Jawaharlal Nehru b) Gulzarilal Nanda c) Gopinath Bordoloi d) Indira Gandhi Q5. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 28 July 1979 - 14 January 1980. a) Jyoti Basu b) Morarji Desai c) Charan Singh d) V. V. Giri Q6. _______________________ served as the Prime Minister of India (21 April 1997 - 19 March 1998). a) Inder Kumar Gujral b) Charan Singh c) H. D. Deve Gowda d) Morarji Desai Q7. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 21 June 1991 - 16 May 1996. a) H. D. Deve Gowda b) P. V. Narasimha Rao c) Atal Bihari Vajpayee d) Chandra Shekhar Q8. ____________________________ was the Prime Minister of India (31 October 1984 - 2 December 1989). a) Chandra Shekhar b) Indira Gandhi c) Rajiv Gandhi d) P. V. Narasimha Rao Q9. -

Leader of the House F

LEADER OF THE HOUSE F. No. RS. 17/5/2005-R & L © RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI http://parliamentofindia.nic.in http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT PUBLISHED BY SECRETARY-GENERAL, RAJYA SABHA AND NEW DELHI PRINTED BY MANAGER, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI-110002. PREFACE This booklet is part of the Rajya Sabha Practice and Procedure Series which seeks to describe, in brief, the importance, duties and functions of the Leader of the House. The booklet is intended to serve as a handy guide for ready reference. The information contained in it is synoptic and not exhaustive. New Delhi DR. YOGENDRA NARAIN February, 2005 Secretary-General THE LEADER OF THE HOUSE Leader of the House in Rajya Sabha Importance of the Office Rule 2(1) of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Council of States (Rajya Sabha) defines There are quite a few functionaries in Parliament who the Leader of Rajya Sabha as follows: render members’ participation in debates more real, effective and meaningful. One of them is the 'Leader of "Leader of the Council" means the Prime Minister, the House'. The Leader of the House is an important if he is a member of the Council, or a Minister who parliamentary functionary who exercises direct influence is a member of the Council and is nominated by the on the course of parliamentary business. Prime Minister to function as the Leader of the Council. Origin of Office in England In Rajya Sabha, the following members have served In England, one of the members of the Government, as the Leaders of the House since 1952: who is primarily responsible to the Prime Minister for the arrangement of the government business in the Name Period House of Commons, is known as the Leader of the House. -

BOOK REVIEW Hardeep Singh Puri,Delusional Politics, (New Delhi

Indian Foreign Affairs Journal Vol. 13, No. 4, October–December 2018, 345-357 BOOK REVIEW Hardeep Singh Puri, Delusional Politics, (New Delhi, Penguin Viking, 2019), Pages: 304, Price: Rs. 360.00 ‘Delusional Politics’ is an authoritative and insider account of the national and global impact of the rise of populism and an era of ‘alternative facts’ and ‘alternative narratives’ which exploits popular angst to capture political power. It is based on three case studies: the Brexit Referendum, the Trump Presidency, and the India Story. Its clinical analysis of delusional politics and decision making on global governance within the UN, based on the author’s personal experience of a wide range of multilateral negotiations, be it nuclear security, climate change, terrorism, and international trade, makes for fascinating reading. Historian, diplomat (with 40 years in the Foreign Service including as India’s Permanent Representative in Geneva and New York), and now Minister for Urban Affairs, the author explains how the globalisation narrative changed radically with the economic slowdown in the West, resulting on the one hand in the Trump Presidency and, on the other, in the disastrous Brexit referendum. The post-Westphalia, liberal democratic order, with its focus on individual rights and the scrutiny of the State changed sharply with the shrinking markets of the West and the rise of international terrorism. Both for Brexit and the Trump phenomenon, the assumption is clear: “We are in the dawn of a credibility crisis”. Data is distorted or manipulated to change a political narrative. It marks the rise of “post-truth politics” which for Brexit and Trump fed on the toxicity of a contrived and false narrative. -

Annual Report 1965-66

1965-66 Contents Jan 01, 1965 CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. India's Neighbours 1-22 II. States in Special Treaty Relations with India 23-26 III. South East Asia 27-32 IV. East Asia 33-35 V. West Asia and North Africa 36-39 VI. Africa south of the Sahara 40-43 VII. Eastern and Western Europe 44-58 VIII. The Americas 59-62 IX. United Nations and International Conferences 63-78 X. Disarmament 79-82 XI. External Publicity 83-88 XII. Technical and Economic Cooperation 89-92 XIII. Passport and Consular Services 93-101 XIV. Organisation and Administration 102-110 111 E.A.-1. APPENDICES PAGE APPENDIX I. Tashkent Declaration 111-112 APPENDIX II. International Conferences, Congresses and Symposia etc. in which India participated 113-117 APPENDIX III. International Organisations of which India is a Member 118-121 APPENDIX IV. Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Meeting, June 1965 : Final Communique 122-130 APPENDIX V. Foreign Diplomatic Missions in India 131-132 APPENDIX VI. Foreign Consular Offices] in India 133-136 APPENDIX VII. List of Distinguished Visitors from abroad 137-139 APPENDIX VIII. Visits of Indian Dignitaries to foreign countries and other Deputations/Dele- gations sponsored by the Ministry 140-143 APPENDIX IX. List of Indian Missions/Posts abroad 144-152 (ii) INDIA UZBEKISTAN Jan 01, 1965 India's Neighbours CHAPTER I INDIA'S NEIGHBOURS BURMA At the invitation of the President of India, the Chairman of the Revolutionary Council of the Union of Burma, General Ne Win paid a state visit to India from Feb 05, 1965 to 12 February, 1965. -

RTI Handbook

PREFACE The Right to Information Act 2005 is a historic legislation in the annals of democracy in India. One of the major objective of this Act is to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority by enabling citizens to access information held by or under the control of public authorities. In pursuance of this Act, the RTI Cell of National Archives of India had brought out the first version of the Handbook in 2006 with a view to provide information about the National Archives of India on the basis of the guidelines issued by DOPT. The revised version of the handbook comprehensively explains the legal provisions and functioning of National Archives of India. I feel happy to present before you the revised and updated version of the handbook as done very meticulously by the RTI Cell. I am thankful to Dr.Meena Gautam, Deputy Director of Archives & Central Public Information Officer and S/Shri Ashok Kaushik, Archivist and Shri Uday Shankar, Assistant Archivist of RTI Cell for assisting in updating the present edition. I trust this updated publication will familiarize the public with the mandate, structure and functioning of the NAI. LOV VERMA JOINT SECRETARY & DGA Dated: 2008 Place: New Delhi Table of Contents S.No. Particulars Page No. ============================================================= 1 . Introduction 1-3 2. Particulars of Organization, Functions & Duties 4-11 3. Powers and Duties of Officers and Employees 12-21 4. Rules, Regulations, Instructions, 22-27 Manual and Records for discharging Functions 5. Particulars of any arrangement that exist for 28-29 consultation with or representation by the members of the Public in relation to the formulation of its policy or implementation thereof 6. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXIV NO.1 MARCH 2018 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.1 MARCH 2018 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION _____________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXIV NO.1 MARCH 2018 _____________________________________________________________ CONTENTS PAGE ADDRESS - Address by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Smt. Sumitra Mahajan at the 137th Assembly of IPU at St. Petersburg, Russian Federation -- - Address by the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Smt. Sumitra Mahajan at the 63rd Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference, Dhaka, Bangladesh -- PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES -- PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS -- PRIVILEGE ISSUES -- PROCEDURAL MATTERS -- DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST -- SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha -- Rajya Sabha -- State Legislatures -- RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST -- APPENDICES -- I. Statement showing the work transacted during the … Thirteenth Session of the Sixteenth Lok Sabha II. Statement showing the work transacted during the … 244th Session of the Rajya Sabha III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of … the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2017 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament … and assented to by the President during the period 1 October to 31 December 2017 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States … and the Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2017 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union … and State Governments during the period 1 October to 31 December 2017 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, the Rajya Sabha … and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories ADDRESS OF THE SPEAKER, LOK SABHA, SMT. SUMITRA MAHAJAN AT THE 137TH ASSEMBLY OF THE INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION (IPU), HELD IN ST. -

India's Nuclear Odyssey

India’s Nuclear Odyssey India’s Nuclear Andrew B. Kennedy Odyssey Implicit Umbrellas, Diplomatic Disappointments, and the Bomb India’s search for secu- rity in the nuclear age is a complex story, rivaling Odysseus’s fabled journey in its myriad misadventures and breakthroughs. Little wonder, then, that it has received so much scholarly attention. In the 1970s and 1980s, scholars focused on the development of India’s nuclear “option” and asked whether New Delhi would ever seek to exercise it.1 After 1990, attention turned to India’s emerg- ing, but still hidden, nuclear arsenal.2 Since 1998, India’s decision to become an overt nuclear power has ushered in a new wave of scholarship on India’s nu- clear history and its dramatic breakthrough.3 In addition, scholars now ask whether India’s and Pakistan’s acquisition of nuclear weapons has stabilized or destabilized South Asia.4 Despite all the attention, it remains difªcult to explain why India merely Andrew B. Kennedy is Lecturer in Policy and Governance at the Crawford School of Economics and Gov- ernment at the Australian National University. He is the author of The International Ambitions of Mao and Nehru: National Efªcacy Beliefs and the Making of Foreign Policy, which is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. The author gratefully acknowledges comments and criticism on earlier versions of this article from Sumit Ganguly, Alexander Liebman, Tanvi Madan, Vipin Narang, Srinath Raghavan, and the anonymous reviewers for International Security. He also wishes to thank all of the Indian ofªcials who agreed to be interviewed for this article. -

Anecdotes About Jawaharlal Nehru

1 Anecdotes about Jawaharlal Nehru Anil K Rajvanshi Phaltan, Maharashtra, India [email protected] This is the 125th birth anniversary year of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru our first Prime Minister and one of the main architects of Independent India. Lots of articles are being written about Pandit ji and hence I thought of writing about what I heard about him from some of his close associates. Too often people do not write anecdotes about these great people and the interesting tidbits are lost forever when a person dies. The people I am going to describe never wrote about their association with Nehru and hence I thought of putting them on record. I have been lucky to have known them and felt that those interesting stories they told me about Nehru need to be told. I saw Pandit Nehru only two times in my life and had no personal interaction with him. Hence all these anecdotes are from the people who knew him closely. The first time I saw Jawahar Lal Nehru was sometime in 1961. Nehru had come to Lucknow for some meeting either at the Central Drug Research Institute (CDRI) or Lucknow University and he was supposed to pass through Hazratganj the main thorough fare of Lucknow. Since my father who was in the Congress Party talked a lot about Nehru, I had expressed a desire to see him. He knew Nehru’s program that day so decided to take me with him so we could stand in front of the Mayfair cinema building in Hazratganj from where his cavalcade would pass. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English .Version)

Nlatla SerIeI, Vol. I. No 4 Tha.... ', DeeemIJer 21. U89 , A..... ' ... 30. I'll (SUa) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English .Version) First Seai.D (Nlntb Lok Sabba) (Yol. I COlJtairu N08. 1 to 9) LOI: SABRA SECRE1'AlUAT NEW DELHI Price, 1 Itt. 6.00 •• , • .' C , '" ".' .1. t; '" CONTENTS [Ninth Series, VoL /, First Session, 198911911 (Saka)] No. 4, Thursday, December 21, 1989/Agrahayana 30, 1911 (Saka) CoLUMNS Members Sworn 1 60 Assent to Bills 1--2 Introduction of Ministers 2-16 Matters Under Rule 377 16-20 (i) Need to convert the narrow gauge railway 16 line between Yelahanka and Bangarpet in Karnataka into bread gauge tine Shri V. Krishna Rao (ii) Need to ban the m~nufadure and sale of 16-17 Ammonium Sulphide in the country Shri Ram Lal Rahi (iii) Need to revise the Scheduled Castes/ 17 Sched uled Tribes list and provide more facilities to backward classes Shri Uttam Rathod (iv) Need to 3et up the proposed project for 18 exploitation of nickel in Sukinda region of Orissa Shri Anadi Charan Das (v) Need to set up full-fledged Doordarshan 18 Kendras in towns having cultural heritage, specially at Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh Shri Anil Shastri (ii) CoLUMNS (vi) Need to set up Purchase Centres in the cotton 18-19 producing districts of Madhya Pradesh Shri Laxmi Narain Pandey (vii) Need for steps to maintain ecological 19 balance in the country Shri Ramashray Prasad Singh (viii) Need to take measures for normalising 19-20 relations between India and Pakistan Prof. Saifuddin Soz (;x) Need to take necessary steps for an amicable 20 solution of the Punjab problem Shri Mandhata Singh Motion of Confidence in the Council of Ministers 20-107 110-131 Shri Vishwanath Pratap Singh 20-21 116-131 Shri A.R. -

A Life of Truth in Politics LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI

jot OXFORD INDIA PAPERBACKS A life of truth in politics LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI A Life of Truth in Politics C. P. SRIVASTAVA DELHI OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS Acknowledgements have gathered documentary material and photographs for this bio graphy from a number of libraries and institutions. To all of them, particularly the following, I wish to express my profound gratitude: INehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi: Professor Ravinder Kumar, director. Dr Mari DcvSharma, deputy director, and librarian and staff. The library of the Ministry of Informat ion and Broadcasting, Govern ment of India, New Delhi: the librarian and staff of the library. All India Radio, New Delhi: the director-general and his staff. The Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi: Dr V.A. Pai Panandiker, director, and his staff. The Servants of the People Society, New Delhi: Shri Satya Pal. The Hindustan Times, New Delhi: I have quoted extensively from this newspaper and am deeply gratcftil also to Mr N. Thiagarajan, former chief photographer, Hindustan Times Group, who has provided the cover photograph and other photographs. The Films Division, Government of India, Bombay, the director and his staff. The Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, Austin, Texas, USA: David Humphrey, supervising archivist; John Wilson, ar chivist; Irene Parra, archivist; Linda Hanson, archivist; Regina Greenwell, archivist; Claudia Anderson, archivist; and Jeremy Duval, staff member. Yale University Library, Connecticut, USA: the librarian and staff of the library. The British Library, London: the librarian and staff of the library. The British Library, Newspaper Library, Colindalc, London: the librarian and staff of the library. -

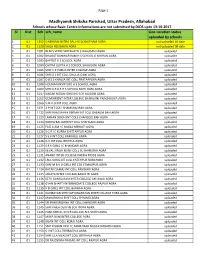

Center Information Not Updated by DIOS 13102017.Xlsx

Page 1 Madhyamik Shiksha Parishad, Uttar Pradesh, Allahabad Schools whose Basic Centre Informations are not submitted by DIOS upto 13-10-2017 Sl Dist Sch sch_name Geo-Location status uploaded by schools 1 01 1352 S NEKRAM NETRA PAL H S SCH KITHAM AGRA not uploaded till date 2 01 1620 SHILA HSS BAGIA AGRA not uploaded till date 3 01 1001 BENI S VEDIC VIDYAVATI I C BALUGANJ AGRA uploaded 4 01 1002 BHAGAT KANWAR RAM H S SCHOOL G M KHAN AGRA uploaded 5 01 1003 BAPTIST H S SCHOOL AGRA uploaded 6 01 1004 CHITRA GUPTA H S SCHOOL SHAHGANJ AGRA uploaded 7 01 1005 SHRI C P PUBLIC INTER COLLEGE AGRA uploaded 8 01 1006 SHRI D J INT COLL DHULIA GANJ AGRA uploaded 9 01 1007 D B S S KHALSA INT COLL PRATAPPURA AGRA uploaded 10 01 1008 HOLMAN INSTITUTE H S SCHOOL AGRA uploaded 11 01 1009 SHRI K R B R H S SCHOOL MOTI GANJ AGRA uploaded 12 01 1037 NAGAR NIGAM GIRLS HS SCH TAJGANJ AGRA uploaded 13 01 1052 GOVERMENT INTER COLLEGE SHAHGANJ PNACHKUIYA AGRA uploaded 14 01 1066 S M A O INT COLL AGRA uploaded 15 01 1071 A P INT COLL SHAMSHADBAD AGRA uploaded 16 01 1122 SHRI RAM SAHAY VERMA INT COLL BASAUNI BAH AGRA uploaded 17 01 1123 LAKHAN SINGH INT COLL CHANGOLI BAH AGRA uploaded 18 01 1124 RADHA BALLABH INT COLL SHAHGANJ AGRA uploaded 19 01 1125 FAIZ A AM I C NAGLA MEWATI AGRA uploaded 20 01 1126 S G R I C KURRA CHITTARPUR AGRA uploaded 21 01 1127 S S V INT COLL KARKAULI AGRA uploaded 22 01 1128 G V INT COLL BRITHLA AGRA uploaded 23 01 1129 S R K GIRLS I C KHANDARI AGRA uploaded 24 01 1130 KEVAL SINGH M INT COLL SUTHARI BAH AGRA uploaded 25 01 1131 ANAND INTER