Sumit Ganguly AVOIDING WAR in KASHMIR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE the COLONIAL CONTEXT: the BIRTH of BANGLADESH in Retrospectt

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE THE COLONIAL CONTEXT: THE BIRTH OF BANGLADESH IN RETROSPECTt By VedP. Nanda* I. INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the Indo-Pakistan War in December 1971, the independent nation-state of Bangladesh was born.' Within the next four months, more than fifty countries had formally recognized the new nation.2 As India's military intervention was primarily responsible for the success of the secessionist movement in what was then known as East Pakistan, and for the creation of a new political entity on the inter- national scene,3 many serious questions stemming from this historic event remain unresolved for the international lawyer. For example: (1) What is the continuing validity of Article 2 (4) of the United Nations Charter?4 (2) What is the current status of the doctrine of humanita- rian intervention in international law?5 (3) What action could the United Nations have taken to avert the Bangladesh crisis?6 (4) What measures are necessary to prevent such tragic occurrences in the fu- ture?7 and (5) What relationship exists between the principle of self- "- This paper is an adapted version of a chapter that will appear in Y. ALEXANDER & R. FRIEDLANDER, SELF-DETERMINATION (1979). * Professor of Law and Director of the International Legal Studies Program, Univer- sity of Denver Law Center. 1. See generally BANGLADESH: CRISIS AND CONSEQUENCES (New Delhi: Deen Dayal Research Institute 1972); D. MANKEKAR, PAKISTAN CUT TO SIZE (1972); PAKISTAN POLITI- CAL SYSTEM IN CRISIS: EMERGENCE OF BANGLADESH (S. Varma & V. Narain eds. 1972). 2. Ebb Tide, THE ECONOMIST, April 8, 1972, at 47. -

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

Operation Gibraltar.Docx

Operation Gibraltar Operation Gibraltar was code name for a military operation launched by the Pakistani military in the Indian administered part of Kashmir. The objective was for Pakistani commandos to infiltrate the Line of Control and instigate the local population to revolt against the Indian government. The operation was a disaster as the local population did not revolt and the infiltration was discovered. This led to the outbreak of the 1965 Indo-Pak war. Operation Gibraltar was an important topic in the Modern Indian History segment of the IAS exam. Background of Operation Gibraltar The Indo-Pakistan war of 1947 resulted in Indian gaining two-thirds of Kashmir. However Pakistan kept looking for opportunities to gain the rest. That opportunity would come following the 1962 Sino-Indian conflict (Began on October 20, 1962). The defeat at the hands of the Chinese military led to major changes in the Indian army in terms of men and equipment. Pakistan, despite being outnumbered, would use its qualitative edge to balance the scales of power before India completed its defence build up. The Rann of Kutch clash (April 9th 1965) in the summer of 1965, where Indian and Pakistani forces clashed, resulted in some positives for Pakistan. Moreover, in December 1963, the disappearance of a holy relic from the Hazratbal shrine in Srinagar, created turmoil among the people in the valley, which was viewed by Pakistan as ideal for revolt. These factors bolstered the Pakistani command's thinking: that the use of covert methods followed by the threat of an all out war would force a resolution in Kashmir Thus Pakistani Military command opted to send in both its regular army and an auxiliary force of Kashmiri locals on their side of the border towards Jammu and Kashmir. -

Khalistan & Kashmir: a Tale of Two Conflicts

123 Matthew Webb: Khalistan & Kashmir Khalistan & Kashmir: A Tale of Two Conflicts Matthew J. Webb Petroleum Institute _______________________________________________________________ While sharing many similarities in origin and tactics, separatist insurgencies in the Indian states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have followed remarkably different trajectories. Whereas Punjab has largely returned to normalcy and been successfully re-integrated into India’s political and economic framework, in Kashmir diminished levels of violence mask a deep-seated antipathy to Indian rule. Through a comparison of the socio- economic and political realities that have shaped the both regions, this paper attempts to identify the primary reasons behind the very different paths that politics has taken in each state. Employing a distinction from the normative literature, the paper argues that mobilization behind a separatist agenda can be attributed to a range of factors broadly categorized as either ‘push’ or ‘pull’. Whereas Sikh separatism is best attributed to factors that mostly fall into the latter category in the form of economic self-interest, the Kashmiri independence movement is more motivated by ‘push’ factors centered on considerations of remedial justice. This difference, in addition to the ethnic distance between Kashmiri Muslims and mainstream Indian (Hindu) society, explains why the politics of separatism continues in Kashmir, but not Punjab. ________________________________________________________________ Introduction Of the many separatist insurgencies India has faced since independence, those in the states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir have proven the most destructive and potent threats to the country’s territorial integrity. Ostensibly separate movements, the campaigns for Khalistan and an independent Kashmir nonetheless shared numerous similarities in origin and tactics, and for a brief time were contemporaneous. -

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Author(s): Haley Duschinski Source: International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Apr., 2008), pp. 41-64 Published by: Springer Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40343840 Accessed: 12-01-2020 07:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of Hindu Studies This content downloaded from 134.114.107.39 on Sun, 12 Jan 2020 07:34:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Haley Duschinski Kashmiri Hindus are a numerically small yet historically privileged cultural and religious community in the Muslim- majority region of Kashmir Valley in Jammu and Kashmir State in India. They all belong to the same caste of Sarasvat Brahmanas known as Pandits. In 1989-90, the majority of Kashmiri Hindus living in Kashmir Valley fled their homes at the onset of conflict in the region, resettling in towns and cities throughout India while awaiting an opportunity to return to their homeland. -

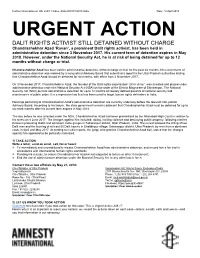

Missing Lawyer at Risk of Torture

Further information on UA: 248/17 Index: ASA 20/8191/2018 India Date: 10 April 2018 URGENT ACTION DALIT RIGHTS ACTIVIST STILL DETAINED WITHOUT CHARGE Chandrashekhar Azad ‘Ravan’, a prominent Dalit rights activist, has been held in administrative detention since 3 November 2017. His current term of detention expires in May 2018. However, under the National Security Act, he is at risk of being detained for up to 12 months without charge or trial. Chandrashekhar Azad has been held in administrative detention, without charge or trial, for the past six months. His current term of administrative detention was ordered by a non-judicial Advisory Board that submitted a report to the Uttar Pradesh authorities stating that Chandrashekhar Azad should be detained for six months, with effect from 2 November 2017. On 3 November 2017, Chandrashekhar Azad, the founder of the Dalit rights organisation “Bhim Army”, was arrested and placed under administrative detention under the National Security Act (NSA) on the order of the District Magistrate of Saharanpur. The National Security Act (NSA) permits administrative detention for up to 12 months on loosely defined grounds of national security and maintenance of public order. It is a repressive law that has been used to target human rights defenders in India. Hearings pertaining to Chandrashekhar Azad’s administrative detention are currently underway before the relevant non-judicial Advisory Board. According to his lawyer, the state government remains adamant that Chandrashekhar Azad must be detained for up to six more months after his current term expires in May 2018. The day before he was arrested under the NSA, Chandrashekhar Azad had been granted bail by the Allahabad High Court in relation to his arrest on 8 June 2017. -

1. Syed Khalid Siraj Subhani 2. Mian Asad Hayaud

PROFILE OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE FILED THEIR INTENTION TO OFFER THEMSELVES TO CONTEST IN THE ELECTION OF DIRECTORS AT THE 11th EXTRAORDINARY GENERAL MEETING SCHEDULED TO BE HELD ON MARCH 17, 2021. 1. Syed Khalid Siraj Subhani Mr. Subhani is a Chemical Engineer with Executive Management Program from Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley and Leadership program from MIT, Boston. A seasoned executive, his career spanned over 33 years with Exxon Chemical Pakistan Limited, which subsequently became Engro Chemical Pakistan Limited and later Engro Corporation Limited. This included long term assignments with Esso Chemical Canada in Edmonton and at ICI site in Billingham UK. Over the years, he worked in numerous senior executive positions at Engro and played instrumental role in growth and diversification of the company to make it one of the largest business conglomerates of Pakistan. Prior to retirement from Engro he worked as President and Chief Executive Officer of Engro Corporation Limited, Engro Fertilisers Limited and Engro Polymer and Chemicals Limited. Mr. Subhani also served as President and Chief Executive Officer of ThalNova Power Thar Private Limited for a period of two years. Earlier Mr. Subhani also served on the board of Engro Corporation Limited (Director), Hub Power Company Limited (Director), Engro Foods Limited (Director), Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company Limited (Director), Laraib Energy Limited (Director), Engro Fertilisers Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Polymer and Chemicals Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Vopak Terminal Limited (Board Chairman), Thar Power Company Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Powergen Qadirpur Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Elengy Terminal (Private) Limited (Board Chairman) and Engro Eximp Agri Products (Private) Limited (Board Chairman). -

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions for Class 3

10 Prime Ministers of India - Captivating GK Questions For Class 3 Answer the following GK Questions on 10 Prime Ministers of India: Q1. Name the first Prime Minister of India who served office (15 August 1947 - 27 May 1964) until his death. a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Jawaharlal Nehru c) Rajendra Prasad d) Lal Bahadur Shastri Q2. _____________________ is the current Prime Minister of India (26 May 2014 – present). a) Narendra Modi b) Atal Bihari Vajpayee c) Manmohan Singh d) Ram Nath Kovind Q3. Who was the Prime Minister of India (9 June 1964 - 11 January 1966) until his death? a) Gulzarilal Nanda b) Charan Singh c) Lal Bahadur Shastri d) Morarji Desai Q4. Who served as Prime Minister of India from 24 January 1966 - 24 March 1977? a) Jawaharlal Nehru b) Gulzarilal Nanda c) Gopinath Bordoloi d) Indira Gandhi Q5. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 28 July 1979 - 14 January 1980. a) Jyoti Basu b) Morarji Desai c) Charan Singh d) V. V. Giri Q6. _______________________ served as the Prime Minister of India (21 April 1997 - 19 March 1998). a) Inder Kumar Gujral b) Charan Singh c) H. D. Deve Gowda d) Morarji Desai Q7. Name the Prime Minister of India who served office from 21 June 1991 - 16 May 1996. a) H. D. Deve Gowda b) P. V. Narasimha Rao c) Atal Bihari Vajpayee d) Chandra Shekhar Q8. ____________________________ was the Prime Minister of India (31 October 1984 - 2 December 1989). a) Chandra Shekhar b) Indira Gandhi c) Rajiv Gandhi d) P. V. Narasimha Rao Q9. -

Leader of the House F

LEADER OF THE HOUSE F. No. RS. 17/5/2005-R & L © RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI http://parliamentofindia.nic.in http://rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT PUBLISHED BY SECRETARY-GENERAL, RAJYA SABHA AND NEW DELHI PRINTED BY MANAGER, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI-110002. PREFACE This booklet is part of the Rajya Sabha Practice and Procedure Series which seeks to describe, in brief, the importance, duties and functions of the Leader of the House. The booklet is intended to serve as a handy guide for ready reference. The information contained in it is synoptic and not exhaustive. New Delhi DR. YOGENDRA NARAIN February, 2005 Secretary-General THE LEADER OF THE HOUSE Leader of the House in Rajya Sabha Importance of the Office Rule 2(1) of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Council of States (Rajya Sabha) defines There are quite a few functionaries in Parliament who the Leader of Rajya Sabha as follows: render members’ participation in debates more real, effective and meaningful. One of them is the 'Leader of "Leader of the Council" means the Prime Minister, the House'. The Leader of the House is an important if he is a member of the Council, or a Minister who parliamentary functionary who exercises direct influence is a member of the Council and is nominated by the on the course of parliamentary business. Prime Minister to function as the Leader of the Council. Origin of Office in England In Rajya Sabha, the following members have served In England, one of the members of the Government, as the Leaders of the House since 1952: who is primarily responsible to the Prime Minister for the arrangement of the government business in the Name Period House of Commons, is known as the Leader of the House. -

NATIONAL ELECTRW POWER REGULATORY AUTHORITY ISLAMIC REPUBLIC of PAKISTAN REGISTRAR No. Mr. Iftikhar Ayub Khan, SU-701, Askari V

NATIONAL ELECTRW POWER REGULATORY AUTHORITY ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKISTAN NEPRA Tower, Attaturk Avenue (East) G-511, Islamabad - Phone: 9206500, Fax: 2600026 REGISTRAR Website: www.nepra.org.Dk, Email: infoneDra.orq.pk No. June 11,2021 Mr. Iftikhar Ayub Khan, SU-701, Askari V, Sector B Malir Cantonment, Karachi, Contact No. 0336-08 12250 Subject: Generation Licence No. DGL/13065/2021 Licence Application No. LAN-13065 Mr. IftIkhar Avub Khan, K-Electric Limited Reference. KEL 's letter No, KE/BPRINEPRA/2021/1073 dared 24. 05.2021('received on 26.05.2021) Enclosed please find herewith Generation Licence No. DGL/13065/202 1 granted by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority to Mr. Iftikhar Ayub Khan for 5.020 kW photo voltaic solar based distributed generation facility located at SU-701, Askari V, Sector B, Malir Cantt, Malir Cantonment, Karachi, pursuant to NEPRA (Alternative & Renewable Energy) Distributed Generation and Net Metering Regulations, 2015. 2. Please quote above mentioned Generation Licence No. for future correspondence. Enclosure: Generation Licence (DGL/13065/2021) fl 0 € (Syed Safeer Hussain) Copy to: 1. Chief Executive Office, Alternative Energy Development Board, 2nd Floor, OPF Building, G-5/2, Islamabad. 2. Chief Executive Officer, K-Electric Limited, KE House, 39 B, Main Sunset Boulevard, DHA Phase-lI, Karachi. 3. Director General, Environment Protection Department, Government of Sindh, Complex Plot No. ST-2/1, Korangi Industrial Area, Karachi. National Electric Power Requlatory Authority (NEPRA) Islamabad—Pakistan GENERATION LICENCE No. DGL11306512021 The Authority hereby grants Generation Licence to Mr. lftikhar Ayub Khan, for 5.02 KW photovoltaic solar based distributed generation facility, having consumer reference number LB 237301, located at SU-701, Askari V, Sector B, Malir Cantt, Malir Cantonment, Karachi under the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (Alternative & Renewable Energy) Distributed Generation and Net Metering Regulations, 2015 (the "A&RE Regulations") for a period of seven (07) years. -

Pakistan's Atomic Bomb and the Search for Security

Pakistan's Atomic Bomb And The Search For Security edited by Zia Mian Gautam Publishers 27 Temple Road, Lahore, Pakistan Printed by Maktaba Jadeed Press, Lahore, Pakistan ©1995 by Zia Mian A publication of the Campaign for Nuclear Sanity and the Sustainable Development Policy Institute Acknowledgements No book is ever produced in isolation. This one in particular is the work of many hands, and minds. Among the people whose contribution has been indispensable, special mention must be made of Nauman Naqvi from SDPI. There is Gautam Publishers, who have taken the risk when others have not. The greatest debts are, as always, personal. They are rarely mentioned, can never be paid, and payment is never asked for. It is enough that they are remembered. Contents Foreword Dr. Mubashir Hasan i Introduction Dr. Zia Mian 1 1. Nuclear Myths And Realities Dr. Pervez Hoodbhoy 3 Bombs for Prestige? 4 Understanding May 1990 8 The Overt-Covert Debate 11 Nuclear War - By Accident 16 The Second Best Option 17 Options for Pakistan 21 2. A False Sense Of Security Lt.-Gen. (rtd.) Mujib ur Rehman Khan 24 A Matter of Perception 25 Useless Nukes 26 A Sterile Pursuit 28 3. The Costs Of Nuclear Security Dr. Zia Mian 30 The Human Costs of Nuclear Programmes 31 Nuclear Accidents 35 Nuclear Guardians 38 Buying Security with Nuclear Weapons 40 The Real Cost of Nuclear Weapons 44 Safety 48 The Social Costs of Nuclear Security 51 Who Benefits? 53 The Ultimate Costs of Nuclear Security 56 4. The Nuclear Arms Race And Fall Of The Soviet Union Dr. -

Pakistan's Nuclear Proliferation Activities and The

Order Code RL32745 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Pakistan’s Nuclear Proliferation Activities and the Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission: U.S. Policy Constraints and Options Updated March 16, 2005 Richard P. Cronin, Coordinator Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division K. Alan Kronstadt Analyst in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Sharon Squassoni Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Pakistan’s Nuclear Proliferation Activities and the Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission: U.S. Policy Constraints and Options Summary In calling for a clear, strong, and long-term commitment to support the military- dominated government of Pakistan despite serious concerns about that country’s nuclear proliferation activities, The Final Report of the 9/11 Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States cast into sharp relief two long-standing contradictions in U.S. policy towards Pakistan and South Asia. First, in over fifty years, the United States and Pakistan have never been able to align their national security objectives except partially and temporarily. Pakistan’s central goal has been to gain U.S. support to bolster its security against India, whereas the United States has tended to view the relationship from the perspective of its global security interests. Second, U.S. nuclear nonproliferation objectives towards Pakistan (and India) repeatedly have been subordinated to other U.S. goals. During the 1980s, Pakistan successfully exploited its importance as a conduit for aid to the anti-Soviet Afghan mujahidin to deter the application of U.S.