Analysis of Joel Chandler Harris's Uncle Remus As Southern Folklore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 11: 331–350, 2011 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2011.03.0028 Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions John G. Watson1,2*, Judith C. Chow1,2, Li Chen1, Xiaoliang Wang1, Thomas M. Merrifield3, Philip M. Fine4, Ken Barker5 1 Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV, USA 89512 2 Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 10 Fenghui South Road, Xi’an High-Tech Zone, Xi’an, China 710075 3 BGI Incorporated, 58 Guinan Street, Waltham, MA, USA, 02451 4 South Coast Air Quality Management District, 21865 Copley Drive, Diamond Bar, CA, USA 91765 5 Sully-Miller Contracting Co., 135 S. State College Boulevard, Brea, CA, USA 92821 ABSTRACT Eight different PM10 samplers with various size-selective inlets and sample flow rates were evaluated for upwind/ downwind assessment of fugitive dust emissions from two sand and gravel operations in southern California during September through October 2008. Continuous data were acquired at one-minute intervals for 24 hours each day. Integrated filters were acquired at five-hour intervals between 1100 and 1600 PDT on each day because winds were most consistent during this period. High-volume (hivol) size-selective inlet (SSI) PM10 Federal Reference Method (FRM) filter samplers were comparable to each other during side-by-side sampling, even under high dust loading conditions. Based on linear regression slope, the BGI low-volume (lovol) PQ200 FRM measured ~18% lower PM10 levels than a nearby hivol SSI in the source-dominated environment, even though tests in ambient environments show they are equivalent. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

Southern Ambivalence: the Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 Southern Ambivalence: The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris William R. Bell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Bell, William R., "Southern Ambivalence: The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625262. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-mr8c-mx50 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Southern Ambivalence: h The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by William R. Bell 1984 ProQuest Number: 10626489 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10626489 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

VIRGIN IAN WRITERS OF FUGITIVE VERSE VIRGINIAN WRITERS FUGITIVE VERSE we with ARMISTEAD C. GORDON, JR., M. A., PH. D, Assistant Proiesso-r of English Literature. University of Virginia I“ .‘ '. , - IV ' . \ ,- w \ . e. < ~\ ,' ’/I , . xx \ ‘1 ‘ 5:" /« .t {my | ; NC“ ‘.- ‘ '\ ’ 1 I Nor, \‘ /" . -. \\ ' ~. I -. Gil-T 'J 1’: II. D' VI. Doctor: .. _ ‘i 8 » $9793 Copyrighted 1923 by JAMES '1‘. WHITE & C0. :To MY FATHER ARMISTEAD CHURCHILL GORDON, A VIRGINIAN WRITER OF FUGITIVE VERSE. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The thanks of the author are due to the following publishers, editors, and individuals for their kind permission to reprint the following selections for which they hold copyright: To Dodd, Mead and Company for “Hold Me Not False” by Katherine Pearson Woods. To The Neale Publishing Company for “1861-1865” by W. Cabell Bruce. To The Times-Dispatch Publishing Company for “The Land of Heart‘s Desire” by Thomas Lomax Hunter. To The Curtis Publishing Company for “The Lane” by Thomas Lomax Hunter (published in The Saturday Eve- ning Post, and copyrighted, 1923, by the Curtis Publishing 00.). To the Johnson Publishing Company for “Desolate” by Fanny Murdaugh Downing (cited from F. V. N. Painter’s Poets of Virginia). To Harper & Brothers for “A Mood” and “A Reed Call” by Charles Washington Coleman. To The Independent for “Life’s Silent Third”: by Charles Washington Coleman. To the Boston Evening Transcript for “Sister Mary Veronica” by Nancy Byrd Turner. To The Century for “Leaves from the Anthology” by Lewis Parke Chamberlayne and “Over the Sea Lies Spain” by Charles Washington Coleman. To Henry Holt and Company for “Mary‘s Dream” by John Lowe and “To Pocahontas” by John Rolfe. -

Why Atlanta for the Permanent Things?

Atlanta and The Permanent Things William F. Campbell, Secretary, The Philadelphia Society Part One: Gone With the Wind The Regional Meetings of The Philadelphia Society are linked to particular places. The themes of the meeting are part of the significance of the location in which we are meeting. The purpose of these notes is to make our members and guests aware of the surroundings of the meeting. This year we are blessed with the city of Atlanta, the state of Georgia, and in particular The Georgian Terrace Hotel. Our hotel is filled with significant history. An overall history of the hotel is found online: http://www.thegeorgianterrace.com/explore-hotel/ Margaret Mitchell’s first presentation of the draft of her book was given to a publisher in the Georgian Terrace in 1935. Margaret Mitchell’s house and library is close to the hotel. It is about a half-mile walk (20 minutes) from the hotel. http://www.margaretmitchellhouse.com/ A good PBS show on “American Masters” provides an interesting view of Margaret Mitchell, “American Rebel”; it can be found on your Roku or other streaming devices: http://www.wgbh.org/programs/American-Masters-56/episodes/Margaret-Mitchell- American-Rebel-36037 The most important day in hotel history was the premiere showing of Gone with the Wind in 1939. Hollywood stars such as Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, and Olivia de Haviland stayed in the hotel. Although Vivien Leigh and her lover, Lawrence Olivier, stayed elsewhere they joined the rest for the pre-Premiere party at the hotel. Our meeting will be deliberating whether the Permanent Things—Truth, Beauty, and Virtue—are in fact, permanent, or have they gone with the wind? In the movie version of Gone with the Wind, the opening title card read: “There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South.. -

Ing Items Have Been Registered

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 29 November 2018 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Cynwulf Rendell and Eleanore Godwin. Joint badge. Or, a heron volant wings addorsed sable, a bordure indented azure. AN TIR Basil Dragonstrike. Alternate name Basil Oldstone. Bjorn of Havok. Transfer of badge to Tir Rígh, Principality of. (Fieldless) A Lisbjerg gripping-beast gules. Bryn MacTeige MacQuharrie. Name. Questions were raised in commentary about the construction of the multi-generational bynames. We have evidence of two-generation bynames using Mac- forms in both Anglicized Irish and Scots. For example, "Names Found in Anglicized Irish Documents," by Mari ingen Briain meic Donnchada (https://s-gabriel.org/names/irish.shtml) contains the examples Cormack m’Teige M’Carthie and Fardorrough m’Emon M’Shehey, among others. "Notes on Name Formation in Scots and Latin Renderings of Gaelic Names" by Alys Mackyntoich (https://alysprojects.blogspot.com/2014/01/notes-on-name-formation-in-scots-and.html) includes the examples Coill McGillespike McDonald and Angus McEane McPhoull, among others. Thus, this name is correctly formed for both Anglicized Irish and Scots. The submitter requested authenticity for 16th century Scottish culture. This request was not summarized on the Letter of Intent. Fortunately, Seraphina Ragged Staff identified the authenticity request during commentary, allowing sufficient time for research. Although it is registerable, the name does not meet the authenticity request because we have no evidence of the given names Bryn or Teige in Scotland; they are both Anglicized Irish forms. Ciaran mac Drosto. Device. Per bend azure and vert, on a bend between an elephant and a griffin statant respectant Or, a pen vert. -

Reflections on William Caxton's 'Reynard the Fox' N.F

REFLECTIONS ON WILLIAM CAXTON'S 'REYNARD THE FOX' N.F. Blake-University of Sheffield Caxton's Reynard the Fox (RF) is a translation of might imply it was at her request or command that he the prose Die Hystorie van Reynaert die Vos printed went to Cologne to learn printing. However, there is by Gerard Leeu at Gouda in 1479. This prose version no evidence that merchants were employed in this is itself based on the earlier poetic Reinaert II from way by members of the nobility like Margaret, and as the fourteenth century. Caxton's version follows the there is evidence that Caxton was governor until at Dutch text fairly closely and narrates how Reynard is least 1470, there isllttle time for him to have been in summoned to Noble's court to answer charges Margaret's servicisince he had arrived in Cologne by brought against him and how he manages to outwit June 1471. In addition, the use of such words as 'ser his opponents; RF has consequently always appeared vant' to describe his relations with Margaret does not the odd man out among Caxton's printed books. It imply that he was in her service, for words like that does not fit in with the courtly and religious material were employed then·· as marks of deference-as was emanating from the press, because it is regarded as still true until recently, for example in letters which the only work which is comic and satirical; and it might end 'your obedient servant'. Even so the does not fit in with the translations from French for dedication of History of Troy to Margaret does in it is the only book translated from Dutch, and Dutch dicate that Caxton was aware of the presence of the was not such a courtly language as French. -

Joel Chandler Harris, Interpreter of the Negro Soul

JOEL CHANDLER HARRIS, LXTERPRETER OF THE NEGRO SOUL BY J. V. NASH THE most enduring of all literature springs from popular folk- lore. It is more than poetry or prose ; it is philosophy, science, psychology, religion, history, ethics. It reflects the groping and aspir- ing soul of a people, in all its manifold reactions to its environment. It is the key which long generations of humble folk have been pain- fully forging, with which to unlock the mysterious door which opens into the Unseen. This unpretending folklore is usually kept alive by word of mouth for many generations before a literary genius discovers it, gathers it together, separates the chaff from the wheat, and gives to the world the harvest of golden grain. For many vears there had been lying unrecognized in America a rich accumulation of folklore in the traditions, the songs, the tales, the proverbs, an.d the quaint philosophy of the plantation Negroes of the South. AVith the breaking up of the old patriarchal life and the advent of modern industrialism, this unique folklore was threatened with a speedy extinction. Doubtless it would have largely faded into oblivion, were it not for the fact that during the 'Seventies and 'Eighties there happened to be sitting at a desk in the office of the Atlanta Constitution the one man who possessed the tempermental qualifications to interpret this folklore, and the ability as a writer to mold it into literature of universal appeal. So it came to pass that this neglected store of plantation folklore was given at last to the world in a series of inimitable stories which for more than forty years have been the delight of children, and of all who are youthful in spirit, wherever the English language is spoken. -

The Human Presence in Robert Henryson's Fables and William Caxton's the History of Reynard the Fox

Good, Julian Russell Peter (2012) The human presence in Robert Henryson's Fables and William Caxton's The History of Reynard the Fox. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3290/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE HUMAN PRESENCE IN ROBERT HENRYSON’S FABLES AND WILLIAM CAXTON’S THE HISTORY OF REYNARD THE FOX Dr. Julian Russell Peter Good Submitted for the degree of Ph.D. Department of Scottish Literature College of Arts University of Glasgow © Dr. Julian R.P. Good. March 2012 ABSTRACT This study is a comparison of the human presence in the text of Robert Henryson’s Fables1, and that of William Caxton’s 1481 edition of The History of Reynard the Fox (Blake:1970). The individual examples of Henryson’s Fables looked at are those that may be called the ‘Reynardian’ fables (Mann:2009); these are The Cock and the Fox; The Fox and the Wolf; The Trial of the Fox; The Fox, the Wolf, and the Cadger, and The Fox, the Wolf, and the Husbandman.2 These fables were selected to provide a parallel focus, through the main protagonists and sources, with the text of The History of Reynard the Fox. -

ARMED FORCES CIP: Taking a Sabbatical from Your Navy Career

Navy • Marine Corps • Coast Guard • Army • Air Force AT AT EASE ARMED FORCES San Diego Navy/Marine Corps Dispatch • www.armedforcesdispatch.com • 619.280.2985 FIFTY SIXTH YEAR NO. 30 Serving active duty and retired military personnel, veterans and civil service employees THURSDAY, JANUARY 26, 2017 by Jim Garamone fense secretary. Mattis retired from the Marine Corps in 2013. WASHINGTON - By a 98-1 vote, the Senate confirmed Marine Mattis is a veteran of the Gulf War and the wars in Iraq and Corps Gen. (Ret.) James Mattis to be secretary of defense Jan. Afghanistan. His military career culminated with service as com- 20, and Vice President Michael Pence administered his oath of mander of U.S. Central Command. office shortly afterward. The secretary was born in Richland, Wash., graduating from Mattis is the first retired general officer to hold the position high school there in 1968 and enlisting in the Marine Corps the since General of the Army George C. Marshall in the early 1950s. following year. He was commissioned in the Marine Corps in 1972 Congress passed a waiver for the retired four-star general to serve after graduating from Central Washington University. in the position, because law requires former service members to have been out of uniform for at least seven years to serve as de- Mattis said his priority as defense sec- retary will be to strengthen military readiness, strengthen U.S. alliances and bring business reforms to the Defense Department. He served as a rifle and weapons platoon commander, and as a lieutenant colonel, he commanded the 1st Battalion, 7th Ma- rines in Operation Desert Storm. -

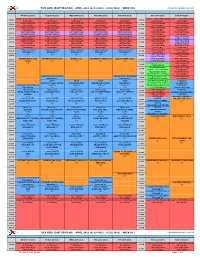

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO