Igusa Integrals and Volume Asymptotics in Analytic and Adelic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analytic Geometry

Guide Study Georgia End-Of-Course Tests Georgia ANALYTIC GEOMETRY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................5 HOW TO USE THE STUDY GUIDE ................................................................................6 OVERVIEW OF THE EOCT .........................................................................................8 PREPARING FOR THE EOCT ......................................................................................9 Study Skills ........................................................................................................9 Time Management .....................................................................................10 Organization ...............................................................................................10 Active Participation ...................................................................................11 Test-Taking Strategies .....................................................................................11 Suggested Strategies to Prepare for the EOCT ..........................................12 Suggested Strategies the Day before the EOCT ........................................13 Suggested Strategies the Morning of the EOCT ........................................13 Top 10 Suggested Strategies during the EOCT .........................................14 TEST CONTENT ........................................................................................................15 -

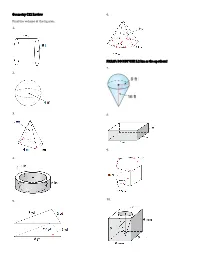

Geometry C12 Review Find the Volume of the Figures. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6

Geometry C12 Review 6. Find the volume of the figures. 1. PREAP: DO NOT USE 5.2 km as the apothem! 7. 2. 3. 8. 9. 4. 10. 5. 11. 16. 17. 12. 18. 13. 14. 19. 15. 20. 21. A sphere has a volume of 7776π in3. What is the radius 33. Two prisms are similar. The ratio of their volumes is of the sphere? 8:27. The surface area of the smaller prism is 72 in2. Find the surface area of the larger prism. 22a. A sphere has a volume of 36π cm3. What is the radius and diameter of the sphere? 22b. A sphere has a volume of 45 ft3. What is the 34. The prisms are similar. approximate radius of the sphere? a. What is the scale factor? 23. The scale factor (ratio of sides) of two similar solids is b. What is the ratio of surface 3:7. What are the ratios of their surface areas and area? volumes? c. What is the ratio of volume? d. Find the volume of the 24. The scale factor of two similar solids is 12:5. What are smaller prism. the ratios of their surface areas and volumes? 35. The prisms are similar. 25. The scale factor of two similar solids is 6:11. What are a. What is the scale factor? the ratios of their surface areas and volumes? b. What is the ratio of surface area? 26. The ratio of the volumes of two similar solids is c. What is the ratio of 343:2197. What is the scale factor (ratio of sides)? volume? d. -

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2 February 15, 2006 . DRAFT Cambridge-MIT Institute Multidisciplinary Design Project This Dictionary/Glossary of Engineering terms has been compiled to compliment the work developed as part of the Multi-disciplinary Design Project (MDP), which is a programme to develop teaching material and kits to aid the running of mechtronics projects in Universities and Schools. The project is being carried out with support from the Cambridge-MIT Institute undergraduate teaching programe. For more information about the project please visit the MDP website at http://www-mdp.eng.cam.ac.uk or contact Dr. Peter Long Prof. Alex Slocum Cambridge University Engineering Department Massachusetts Institute of Technology Trumpington Street, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Cambridge. Cambridge MA 02139-4307 CB2 1PZ. USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] tel: +44 (0) 1223 332779 tel: +1 617 253 0012 For information about the CMI initiative please see Cambridge-MIT Institute website :- http://www.cambridge-mit.org CMI CMI, University of Cambridge Massachusetts Institute of Technology 10 Miller’s Yard, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Mill Lane, Cambridge MA 02139-4307 Cambridge. CB2 1RQ. USA tel: +44 (0) 1223 327207 tel. +1 617 253 7732 fax: +44 (0) 1223 765891 fax. +1 617 258 8539 . DRAFT 2 CMI-MDP Programme 1 Introduction This dictionary/glossary has not been developed as a definative work but as a useful reference book for engi- neering students to search when looking for the meaning of a word/phrase. It has been compiled from a number of existing glossaries together with a number of local additions. -

Chapter 1: Analytic Geometry

1 Analytic Geometry Much of the mathematics in this chapter will be review for you. However, the examples will be oriented toward applications and so will take some thought. In the (x,y) coordinate system we normally write the x-axis horizontally, with positive numbers to the right of the origin, and the y-axis vertically, with positive numbers above the origin. That is, unless stated otherwise, we take “rightward” to be the positive x- direction and “upward” to be the positive y-direction. In a purely mathematical situation, we normally choose the same scale for the x- and y-axes. For example, the line joining the origin to the point (a,a) makes an angle of 45◦ with the x-axis (and also with the y-axis). In applications, often letters other than x and y are used, and often different scales are chosen in the horizontal and vertical directions. For example, suppose you drop something from a window, and you want to study how its height above the ground changes from second to second. It is natural to let the letter t denote the time (the number of seconds since the object was released) and to let the letter h denote the height. For each t (say, at one-second intervals) you have a corresponding height h. This information can be tabulated, and then plotted on the (t, h) coordinate plane, as shown in figure 1.0.1. We use the word “quadrant” for each of the four regions into which the plane is divided by the axes: the first quadrant is where points have both coordinates positive, or the “northeast” portion of the plot, and the second, third, and fourth quadrants are counted off counterclockwise, so the second quadrant is the northwest, the third is the southwest, and the fourth is the southeast. -

Hydraulics Manual Glossary G - 3

Glossary G - 1 GLOSSARY OF HIGHWAY-RELATED DRAINAGE TERMS (Reprinted from the 1999 edition of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials Model Drainage Manual) G.1 Introduction This Glossary is divided into three parts: · Introduction, · Glossary, and · References. It is not intended that all the terms in this Glossary be rigorously accurate or complete. Realistically, this is impossible. Depending on the circumstance, a particular term may have several meanings; this can never change. The primary purpose of this Glossary is to define the terms found in the Highway Drainage Guidelines and Model Drainage Manual in a manner that makes them easier to interpret and understand. A lesser purpose is to provide a compendium of terms that will be useful for both the novice as well as the more experienced hydraulics engineer. This Glossary may also help those who are unfamiliar with highway drainage design to become more understanding and appreciative of this complex science as well as facilitate communication between the highway hydraulics engineer and others. Where readily available, the source of a definition has been referenced. For clarity or format purposes, cited definitions may have some additional verbiage contained in double brackets [ ]. Conversely, three “dots” (...) are used to indicate where some parts of a cited definition were eliminated. Also, as might be expected, different sources were found to use different hyphenation and terminology practices for the same words. Insignificant changes in this regard were made to some cited references and elsewhere to gain uniformity for the terms contained in this Glossary: as an example, “groundwater” vice “ground-water” or “ground water,” and “cross section area” vice “cross-sectional area.” Cited definitions were taken primarily from two sources: W.B. -

Glossary of Terms

GLOSSARY OF TERMS For the purpose of this Handbook, the following definitions and abbreviations shall apply. Although all of the definitions and abbreviations listed below may have not been used in this Handbook, the additional terminology is provided to assist the user of Handbook in understanding technical terminology associated with Drainage Improvement Projects and the associated regulations. Program-specific terms have been defined separately for each program and are contained in pertinent sub-sections of Section 2 of this handbook. ACRONYMS ASTM American Society for Testing Materials CBBEL Christopher B. Burke Engineering, Ltd. COE United States Army Corps of Engineers EPA Environmental Protection Agency IDEM Indiana Department of Environmental Management IDNR Indiana Department of Natural Resources NRCS USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service SWCD Soil and Water Conservation District USDA United States Department of Agriculture USFWS United States Fish and Wildlife Service DEFINITIONS AASHTO Classification. The official classification of soil materials and soil aggregate mixtures for highway construction used by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Abutment. The sloping sides of a valley that supports the ends of a dam. Acre-Foot. The volume of water that will cover 1 acre to a depth of 1 ft. Aggregate. (1) The sand and gravel portion of concrete (65 to 75% by volume), the rest being cement and water. Fine aggregate contains particles ranging from 1/4 in. down to that retained on a 200-mesh screen. Coarse aggregate ranges from 1/4 in. up to l½ in. (2) That which is installed for the purpose of changing drainage characteristics. -

Perimeter, Area, and Volume

Perimeter, Area, and Volume Perimeter is a measurement of length. It is the distance around something. We use perimeter when building a fence around a yard or any place that needs to be enclosed. In that case, we would measure the distance in feet, yards, or meters. In math, we usually measure the perimeter of polygons. To find the perimeter of any polygon, we add the lengths of the sides. 2 m 2 m P = 2 m + 2 m + 2 m = 6 m 2 m 3 ft. 1 ft. 1 ft. P = 1 ft. + 1 ft. + 3 ft. + 3 ft. = 8 ft. 3ft When we measure perimeter, we always use units of length. For example, in the triangle above, the unit of length is meters. For the rectangle above, the unit of length is feet. PRACTICE! 1. What is the perimeter of this figure? 5 cm 3.5 cm 3.5 cm 2 cm 2. What is the perimeter of this figure? 2 cm Area Perimeter, Area, and Volume Remember that area is the number of square units that are needed to cover a surface. Think of a backyard enclosed with a fence. To build the fence, we need to know the perimeter. If we want to grow grass in the backyard, we need to know the area so that we can buy enough grass seed to cover the surface of yard. The yard is measured in square feet. All area is measured in square units. The figure below represents the backyard. 25 ft. The area of a square Finding the area of a square: is found by multiplying side x side. -

Unit 5 Area, the Pythagorean Theorem, and Volume Geometry

Unit 5 Area, the Pythagorean Theorem, and Volume Geometry ACC Unit Goals – Stage 1 Number of Days: 34 days 2/27/17 – 4/13/17 Unit Description: Deriving new formulas from previously discovered ones, the students will leave Unit 5 with an understanding of area and volume formulas for polygons, circles and their three-dimensional counterparts. Unit 5 seeks to have the students develop and describe a process whereby they are able to solve for areas and volumes in both procedural and applied contexts. Units of measurement are emphasized as a method of checking one’s approach to a solution. Using their study of circles from Unit 3, the students will dissect the Pythagorean Theorem. Through this they will develop properties of the special right triangles: 45°, 45°, 90° and 30°, 60°, 90°. Algebra skills from previous classes lead students to understand the connection between the distance formula and the Pythagorean Theorem. In all instances, surface area will be generated using the smaller pieces from which a given shape is constructed. The student will, again, derive new understandings from old ones. Materials: Construction tools, construction paper, patty paper, calculators, Desmos, rulers, glue sticks (optional), sets of geometric solids, pennies and dimes (Explore p. 458), string, protractors, paper clips, square, isometric and graph paper, sand or water, plastic dishpan Standards for Mathematical Transfer Goals Practice Students will be able to independently use their learning to… SMP 1 Make sense of problems • Make sense of never-before-seen problems and persevere in solving them. and persevere in solving • Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. -

Pressure Vs. Volume and Boyle's

Pressure vs. Volume and Boyle’s Law SCIENTIFIC Boyle’s Law Introduction In 1642 Evangelista Torricelli, who had worked as an assistant to Galileo, conducted a famous experiment demonstrating that the weight of air would support a column of mercury about 30 inches high in an inverted tube. Torricelli’s experiment provided the first measurement of the invisible pressure of air. Robert Boyle, a “skeptical chemist” working in England, was inspired by Torricelli’s experiment to measure the pressure of air when it was compressed or expanded. The results of Boyle’s experiments were published in 1662 and became essentially the first gas law—a mathematical equation describing the relationship between the volume and pressure of air. What is Boyle’s law and how can it be demonstrated? Concepts • Gas properties • Pressure • Boyle’s law • Kinetic-molecular theory Background Open end Robert Boyle built a simple apparatus to measure the relationship between the pressure and volume of air. The apparatus ∆h ∆h = 29.9 in. Hg consisted of a J-shaped glass tube that was Sealed end 1 sealed at one end and open to the atmosphere V2 = /2V1 Trapped air (V1) at the other end. A sample of air was trapped in the sealed end by pouring mercury into Mercury the tube (see Figure 1). In the beginning of (Hg) the experiment, the height of the mercury Figure 1. Figure 2. column was equal in the two sides of the tube. The pressure of the air trapped in the sealed end was equal to that of the surrounding air and equivalent to 29.9 inches (760 mm) of mercury. -

Chapter 13: Volume

• Lessons 13-1, 13-2, and 13-3 Find volumes of Key Vocabulary prisms, cylinders, pyramids, cones, and spheres. • volume (p. 688) • Lesson 13-4 Identify congruent and similar • similar solids (p. 707) solids, and state the properties of similar solids. • congruent solids (p. 707) • Lesson 13-5 Graph solids in space, and use the • ordered triple (p. 714) Distance and Midpoint Formulas in space. Volcanoes like those found in Lassen Volcanic National Park, California, are often shaped like cones. By applying the formula for volume of a cone, you can find the amount of material in a volcano. You will learn more about volcanoes in Lesson 13-2. 686 Chapter 13 Volume Ron Watts/CORBIS Prerequisite Skills To be successful in this chapter, you’ll need to master these skills and be able to apply them in problem-solving situations. Review these skills before beginning Chapter 13. For Lesson 13-1 Pythagorean Theorem Find the value of the variable in each equation. (For review, see Lesson 7-2.) 1. a2 ϩ 122 ϭ 132 2. 4͙3ෆ2 ϩ b2 ϭ 82 3. a2 ϩ a2 ϭ 3͙2ෆ2 4. b2 ϩ 3b2 ϭ 192 5. 256 ϩ 72 ϭ c2 6. 144 ϩ 122 ϭ c2 For Lesson 13-2 Area of Polygons Find the area of each regular polygon. (For review, see Lesson 11-3.) 7. hexagon with side length 7.2 cm 8. hexagon with side length 7 ft 9. octagon with side length 13.4 mm 10. octagon with side length 10 in. For Lesson 13-4 Exponential Expressions Simplify. -

Derivation of Pressure Loss to Leak Rate Formula from the Ideal Gas Law

Derivation of Pressure loss to Leak Rate Formula from the Ideal Gas Law APPLICATION BULLETIN #143 July, 2004 Ideal Gas Law PV = nRT P (pressure) V (volume) n (number of moles of gas) T (temperature) R(constant) After t seconds, if the leak rate is L.R (volume of gas that escapes per second), the moles of gas lost from the test volume will be: L.R. (t) Patm Nlost = -------------------- RT And the moles remaining in the volume will be: PV L.R. (t) Patm n’ = n – Nl = ----- - ------------------- RT RT Assuming a constant temperature, the pressure after time (t) is: PV L.R. (t) Patm ------ - --------------- RT n’ RT RT RT L.R. (t) Patm P’ = ------------ = ------------------------- = P - ------------------ V V V L.R. (t) Patm dPLeak = P - P’ = ------------------ V Solving for L.R. yields: V dPLeak L.R. = -------------- t Patm The test volume, temperature, and Patm are considered constants under test conditions. The leak rate is calculated for the volume of gas (measured under standard atmospheric conditions) per time that escapes from the part. Standard atmospheric conditions (i.e. 14.696 psi, 20 C) are defined within the Non- Destructive Testing Handbook, Second Edition, Volume One Leak Testing, by the American Society of Nondestructive Testing. Member of TASI - A Total Automated Solutions Inc. Company 5555 Dry Fork Road Cleves, OH 45002 Tel (513) 367-6699 Fax (513) 367-5426 Website: http://www.cincinnati-test.com Email: [email protected] Because most testing is performed without adequate fill and stabilization time to allow for all the dynamic, exponential effects of temperature, volume change, and virtual leaks produced by the testing process to completely stop, there will be a small and fairly consistent pressure loss associated with a non- leaking master part. -

Measuring Density

Measuring Density Background All matter has mass and volume. Mass is a measure of the amount of matter an object has. Its measure is usually given in grams (g) or kilograms (kg). Volume is the amount of space an object occupies. There are numerous units for volume including liters (l), meters cubed (m3), and gallons (gal). Mass and volume are physical properties of matter and may vary with different objects. For example, it is possible for two pieces of metal to be made out of the same material yet for one piece to be bigger than the other. If the first piece of metal is twice as large as the second, then you would expect that this piece is also twice as heavy (or have twice the mass) as the first. If both pieces of metal are made of the same material the ratio of the mass and volume will be the same. We define density (ρ) as the ratio of the mass of an object to the volume it occupies. The equation is given by: M ρ = (1.1) V here the symbol M stands for the mass of the object, and V the volume. Density has the units of mass divided by volume such as grams per centimeters cube (g/cm3) or kilograms per liter (kg/l). Sample Problem #1 A block of wood has a mass of 8 g and occupies a volume of 10 cm3. What is its density? Solution 8g The density will be = 0.8g / cm 3 . 10cm 3 This means that every centimeter cube of this wood will have a mass of 0.8 grams.