Pressure Vs. Volume and Boyle's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analytic Geometry

Guide Study Georgia End-Of-Course Tests Georgia ANALYTIC GEOMETRY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................5 HOW TO USE THE STUDY GUIDE ................................................................................6 OVERVIEW OF THE EOCT .........................................................................................8 PREPARING FOR THE EOCT ......................................................................................9 Study Skills ........................................................................................................9 Time Management .....................................................................................10 Organization ...............................................................................................10 Active Participation ...................................................................................11 Test-Taking Strategies .....................................................................................11 Suggested Strategies to Prepare for the EOCT ..........................................12 Suggested Strategies the Day before the EOCT ........................................13 Suggested Strategies the Morning of the EOCT ........................................13 Top 10 Suggested Strategies during the EOCT .........................................14 TEST CONTENT ........................................................................................................15 -

History of Hyperbaric Medicine ROBERT S

American Osteopathic College of Occupational and Preventive Medicine 2015 Mid Year Educational Conference, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida How Did We Get From Here History of Hyperbaric Medicine ROBERT S. MICHAELSON, DO, MPH MARCH 14, 2015 To Here 3 History of Hyperbaric Medicine Discuss history of diving Discovery of the atmosphere Five major milestones in the development of hyperbaric medicine Triger’s caisson Eads and Brooklyn Bridge Haldane and staged decompression Rescue of the USS Squalus Donnell and Norton 5 Gourd Breathing About 375 AD Diving as a Profession Salvage Operations From as early as 9th century BC Pay scale based on depth of dive Military Operations Early attempts to bore into hull of ships or attach crude explosives to vessels Confined to shallow waters and for short duration dives Very Hard to be Stealthy and Effective T-1 American Osteopathic College of Occupational and Preventive Medicine 2015 Mid Year Educational Conference, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida DivingHood by Flavius Vegetius Renatus about 375 AD in Leonardo’s (1452-1519) Design For Swim Fins Epitome Institutionum Rei Militaris Diving Rig of Niccolo Tartaglia Canon Recovery Mid-1600’s about 1551 Probably First Diving Bell Mid-1600’s T-2 American Osteopathic College of Occupational and Preventive Medicine 2015 Mid Year Educational Conference, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida T-3 American Osteopathic College of Occupational and Preventive Medicine 2015 Mid Year Educational Conference, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida Diving as a Profession Salvage Operations From as early as 9th century BC Pay scale based on depth on dive Military Operations Early attempts to bore into hull of ships or attach crude explosives to vessels Confined to shallow waters and for short duration dives Very Hard to be Stealthy and Effective Diving Bell-1664 Klingert’s Diving Suit -1797 The Vasa, a Swedish ship sunk within a This equipment is the first to be called mile of her maidenvoyage in 1628. -

Role and Important of Hydrogen in Plant Metabolism

Kheyrodin and Kheyrodin, World J. Biol. Med. Science Volume 4 (3) 13-20, 2017 Indexed, Abstracted and Cited: Index Copernicus International (Poland), ISRA Journal Impact Factor, International Impact Factor Services (IIFS), Directory of Research Journals Indexing (DRJI), International Institute of Organized Research and Scientific Indexing Services, Cosmos Science Foundation (South-East Asia), International Innovative Journal Impact Factor, Einstein Institute for Scientific Information {EISI}, Directory of Open Access Scholarly Resources, Science Indexing Library (UAE), Swedish Scientific Publication (Sweden), citefactor.org journals indexing, Directory Indexing of International Research Journals World Journal of Biology and Medical Sciences Published by Society for Advancement of Science® ISSN 2349-0063 (Online/Electronic) Volume 4, Issue-3, 13-20, July to September, 2017 Journal Impact Factor: 4.197 WJBMS 04/03/119/2017 All rights reserved www.sasjournals.com A Double Blind Peer Reviewed Journal / Refereed Journal [email protected]/[email protected] REVIEW ARTICLE Received: 04/08/2017 Revised: 04/09/2017 Accepted: 05/09/2017 Role and Important of Hydrogen in Plant Metabolism Hamid Kheyrodin and *Sadaf Kheyrodin Faculty of Desert Science, Semnan University, Iran *Urban Planning in Mashad Azad University, Iran ABSTRACT Hydrogen is the simplest and most abundant element in the entire universe. According to astrophysicist David Palmer, about 75 percent of all the known elemental matter that exists is composed of hydrogen. The nucleus of a hydrogen atom is made out of a single proton, which is a positively charged particle. One electron orbits around the outside of the nucleus. Neutrons, which can be found in all other elements, do not exist in the most common form of hydrogen.Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is produced predominantly in plant cells during photosynthesis and photorespiration, and to a lesser extent, in respiration processes. -

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time

Sanitization: Concentration, Temperature, and Exposure Time Did you know? According to the CDC, contaminated equipment is one of the top five risk factors that contribute to foodborne illnesses. Food contact surfaces in your establishment must be cleaned and sanitized. This can be done either by heating an object to a high enough temperature to kill harmful micro-organisms or it can be treated with a chemical sanitizing compound. 1. Heat Sanitization: Allowing a food contact surface to be exposed to high heat for a designated period of time will sanitize the surface. An acceptable method of hot water sanitizing is by utilizing the three compartment sink. The final step of the wash, rinse, and sanitizing procedure is immersion of the object in water with a temperature of at least 170°F for no less than 30 seconds. The most common method of hot water sanitizing takes place in the final rinse cycle of dishwashing machines. Water temperature must be at least 180°F, but not greater than 200°F. At temperatures greater than 200°F, water vaporizes into steam before sanitization can occur. It is important to note that the surface temperature of the object being sanitized must be at 160°F for a long enough time to kill the bacteria. 2. Chemical Sanitization: Sanitizing is also achieved through the use of chemical compounds capable of destroying disease causing bacteria. Common sanitizers are chlorine (bleach), iodine, and quaternary ammonium. Chemical sanitizers have found widespread acceptance in the food service industry. These compounds are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and consequently require labeling with the word “Sanitizer.” The labeling should also include what concentration to use, data on minimum effective uses and warnings of possible health hazards. -

Scuba Diving History

Scuba diving history Scuba history from a diving bell developed by Guglielmo de Loreno in 1535 up to John Bennett’s dive in the Philippines to amazing 308 meter in 2001 and much more… Humans have been diving since man was required to collect food from the sea. The need for air and protection under water was obvious. Let us find out how mankind conquered the sea in the quest to discover the beauty of the under water world. 1535 – A diving bell was developed by Guglielmo de Loreno. 1650 – Guericke developed the first air pump. 1667 – Robert Boyle observes the decompression sickness or “the bends”. After decompression of a snake he noticed gas bubbles in the eyes of a snake. 1691 – Another diving bell a weighted barrels, connected with an air pipe to the surface, was patented by Edmund Halley. 1715 – John Lethbridge built an underwater cylinder that was supplied via an air pipe from the surface with compressed air. To prevent the water from entering the cylinder, greased leather connections were integrated at the cylinder for the operators arms. 1776 – The first submarine was used for a military attack. 1826 – Charles Anthony and John Deane patented a helmet for fire fighters. This helmet was used for diving too. This first version was not fitted to the diving suit. The helmet was attached to the body of the diver with straps and air was supplied from the surfa 1837 – Augustus Siebe sealed the diving helmet of the Deane brothers’ to a watertight diving suit and became the standard for many dive expeditions. -

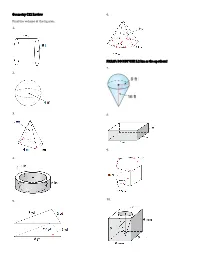

Geometry C12 Review Find the Volume of the Figures. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6

Geometry C12 Review 6. Find the volume of the figures. 1. PREAP: DO NOT USE 5.2 km as the apothem! 7. 2. 3. 8. 9. 4. 10. 5. 11. 16. 17. 12. 18. 13. 14. 19. 15. 20. 21. A sphere has a volume of 7776π in3. What is the radius 33. Two prisms are similar. The ratio of their volumes is of the sphere? 8:27. The surface area of the smaller prism is 72 in2. Find the surface area of the larger prism. 22a. A sphere has a volume of 36π cm3. What is the radius and diameter of the sphere? 22b. A sphere has a volume of 45 ft3. What is the 34. The prisms are similar. approximate radius of the sphere? a. What is the scale factor? 23. The scale factor (ratio of sides) of two similar solids is b. What is the ratio of surface 3:7. What are the ratios of their surface areas and area? volumes? c. What is the ratio of volume? d. Find the volume of the 24. The scale factor of two similar solids is 12:5. What are smaller prism. the ratios of their surface areas and volumes? 35. The prisms are similar. 25. The scale factor of two similar solids is 6:11. What are a. What is the scale factor? the ratios of their surface areas and volumes? b. What is the ratio of surface area? 26. The ratio of the volumes of two similar solids is c. What is the ratio of 343:2197. What is the scale factor (ratio of sides)? volume? d. -

Atomic History Project Background: If You Were Asked to Draw the Structure of an Atom, What Would You Draw?

Atomic History Project Background: If you were asked to draw the structure of an atom, what would you draw? Throughout history, scientists have accepted five major different atomic models. Our perception of the atom has changed from the early Greek model because of clues or evidence that have been gathered through scientific experiments. As more evidence was gathered, old models were discarded or improved upon. Your task is to trace the atomic theory through history. Task: 1. You will create a timeline of the history of the atomic model that includes all of the following components: A. Names of 15 of the 21 scientists listed below B. The year of each scientist’s discovery that relates to the structure of the atom C. 1- 2 sentences describing the importance of the discovery that relates to the structure of the atom Scientists for the timeline: *required to be included • Empedocles • John Dalton* • Ernest Schrodinger • Democritus* • J.J. Thomson* • Marie & Pierre Curie • Aristotle • Robert Millikan • James Chadwick* • Evangelista Torricelli • Ernest • Henri Becquerel • Daniel Bernoulli Rutherford* • Albert Einstein • Joseph Priestly • Niels Bohr* • Max Planck • Antoine Lavoisier* • Louis • Michael Faraday • Joseph Louis Proust DeBroglie* Checklist for the timeline: • Timeline is in chronological order (earliest date to most recent date) • Equal space is devoted to each year (as on a number line) • The eight (8) *starred scientists are included with correct dates of their discoveries • An additional seven (7) scientists of your choice (from -

Physics of Gases and Phenomena of Heat Evangelista Torricelli (1608-1647)

Physics of gases and phenomena of heat Evangelista Torricelli (1608-1647) ”...We have made many vessels of glass like those shown as A and B and with tubes two cubits long. These were filled with quicksilver, the open end was closed with the finger, and they were then inverted in a vessel where there was quicksilver C; then we saw that an empty space was formed and that nothing happened in the vessel when this space was formed; the tube between A and D remained always full to the height of a cubit and a quarter and an inch high... Water also in a similar tube, though a much longer one, will rise to about 18 cubits, that is, as much more than quicksilver does as quicksilver is heavier than water, so as to be in equilibrium with the same cause which acts on the one and the other...” Letter to Michelangelo Ricci, June 11, 1644 Evangelista Torricelli (1608-1647) ”We live immersed at the bottom of a sea of elemental air, which by experiment undoubtedly has weight, and so much weight that the densest air in the neighbourhood of the surface of the earth weighs about one four-hundredth part of the weight of water...” Letter to Michelangelo Ricci, June 11, 1644 In July 1647 Valeriano Magni performed experiments on the vacuum in the presence of the King of Poland at the Royal Castle in Warsaw Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) ”I am searching for information which could help decide whether the action attributed to horror vacui really results from it or perhaps is caused by gravity and the pressure of air. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS Introductory Information C

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS Introductory Information C. L. Young, R. Battino, and H. L. Clever INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the literature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uniform format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of sufficient accuracy are available values are recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation is given to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are published on consecutive pages. The following paper by E. Wilhelm gives a rigorous thermodynamic treatment on the solubility of gases in liquids. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solubility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas-liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solubility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the criti cal temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solubility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the particular worker concerned. -

Pressure Diffusion Waves in Porous Media

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Title Pressure diffusion waves in porous media Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5bh9f6c4 Authors Silin, Dmitry Korneev, Valeri Goloshubin, Gennady Publication Date 2003-04-08 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Pressure diffusion waves in porous media Dmitry Silin* and Valeri Korneev, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Gennady Goloshubin, University of Houston Summary elastic porous medium. Such a model results in a parabolic pressure diffusion equation. Its validity has been Pressure diffusion wave in porous rocks are under confirmed and “canonized”, for instance, in transient consideration. The pressure diffusion mechanism can pressure well test analysis, where it is used as the main tool provide an explanation of the high attenuation of low- since 1930th, see e.g. Earlougher (1977) and Barenblatt et. frequency signals in fluid-saturated rocks. Both single and al., (1990). The basic assumptions of this model make it dual porosity models are considered. In either case, the applicable specifically in the low-frequency range of attenuation coefficient is a function of the frequency. pressure fluctuations. Introduction Theories describing wave propagation in fluid-bearing porous media are usually derived from Biot’s theory of poroelasticity (Biot 1956ab, 1962). However, the observed high attenuation of low-frequency waves (Goloshubin and Korneev, 2000) is not well predicted by this theory. One of possible reasons for difficulties in detecting Biot waves in real rocks is in the limitations imposed by the assumptions underlying Biot’s equations. Biot (1956ab, 1962) derived his main equations characterizing the mechanical motion of elastic porous fluid-saturated rock from the Hamiltonian Principle of Least Action. -

Named Units of Measurement

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Named-Units.pdf 1 NAMED UNITS OF MEASUREMENT © Dr. John Andraos, 2000 - 2013 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ Atomic mass unit (u, Da) John Dalton 6 September 1766 - 27 July 1844 British, b. Eaglesfield, near Cockermouth, Cumberland, England Dalton (1/12th mass of C12 atom) Dalton's atomic theory Dalton, J., A New System of Chemical Philosophy , R. Bickerstaff: London, 1808 - 1827. Biographical References: Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D ., Biographical Encyclopedia of Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Named-Units.pdf 2 Scientists , Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists , Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Maurer, James F. (ed.) Concise Dictionary of Scientific Biography , Charles Scribner's Sons: New York, 1981 Abbott, David (ed.), The Biographical Dictionary of Scientists: Chemists , Peter Bedrick Books: New York, 1983 Partington, J.R., A History of Chemistry , Vol. III, Macmillan and Co., Ltd.: London, 1962, p. 755 Greenaway, F. Endeavour 1966 , 25 , 73 Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1844 , 60 , 528-530 Thackray, A. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.), Dictionary of Scientific Biography , Charles Scribner & Sons: New York, 1973, Vol. 3, 573 Clarification on symbols used: personal communication on April 26, 2013 from Prof. O. David Sparkman, Pacific Mass Spectrometry Facility, University of the Pacific, Stockton, CA. Capacitance (Farads, F) Michael Faraday 22 September 1791 - 25 August 1867 British, b. -

What Is High Blood Pressure?

ANSWERS Lifestyle + Risk Reduction by heart High Blood Pressure BLOOD PRESSURE SYSTOLIC mm Hg DIASTOLIC mm Hg What is CATEGORY (upper number) (lower number) High Blood NORMAL LESS THAN 120 and LESS THAN 80 ELEVATED 120-129 and LESS THAN 80 Pressure? HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE 130-139 or 80-89 (HYPERTENSION) Blood pressure is the force of blood STAGE 1 pushing against blood vessel walls. It’s measured in millimeters of HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE 140 OR HIGHER or 90 OR HIGHER mercury (mm Hg). (HYPERTENSION) STAGE 2 High blood pressure (HBP) means HYPERTENSIVE the pressure in your arteries is higher CRISIS HIGHER THAN 180 and/ HIGHER THAN 120 than it should be. Another name for (consult your doctor or immediately) high blood pressure is hypertension. Blood pressure is written as two numbers, such as 112/78 mm Hg. The top, or larger, number (called Am I at higher risk of developing HBP? systolic pressure) is the pressure when the heart There are risk factors that increase your chances of developing HBP. Some you can control, and some you can’t. beats. The bottom, or smaller, number (called diastolic pressure) is the pressure when the heart Those that can be controlled are: rests between beats. • Cigarette smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke • Diabetes Normal blood pressure is below 120/80 mm Hg. • Being obese or overweight If you’re an adult and your systolic pressure is 120 to • High cholesterol 129, and your diastolic pressure is less than 80, you have elevated blood pressure. High blood pressure • Unhealthy diet (high in sodium, low in potassium, and drinking too much alcohol) is a systolic pressure of 130 or higher,or a diastolic pressure of 80 or higher, that stays high over time.