AREA and VOLUME WHERE DO the FORMULAS COME FROM? Roger Yarnell John Carroll University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analytic Geometry

Guide Study Georgia End-Of-Course Tests Georgia ANALYTIC GEOMETRY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................5 HOW TO USE THE STUDY GUIDE ................................................................................6 OVERVIEW OF THE EOCT .........................................................................................8 PREPARING FOR THE EOCT ......................................................................................9 Study Skills ........................................................................................................9 Time Management .....................................................................................10 Organization ...............................................................................................10 Active Participation ...................................................................................11 Test-Taking Strategies .....................................................................................11 Suggested Strategies to Prepare for the EOCT ..........................................12 Suggested Strategies the Day before the EOCT ........................................13 Suggested Strategies the Morning of the EOCT ........................................13 Top 10 Suggested Strategies during the EOCT .........................................14 TEST CONTENT ........................................................................................................15 -

Chapter 11. Three Dimensional Analytic Geometry and Vectors

Chapter 11. Three dimensional analytic geometry and vectors. Section 11.5 Quadric surfaces. Curves in R2 : x2 y2 ellipse + =1 a2 b2 x2 y2 hyperbola − =1 a2 b2 parabola y = ax2 or x = by2 A quadric surface is the graph of a second degree equation in three variables. The most general such equation is Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + Dxy + Exz + F yz + Gx + Hy + Iz + J =0, where A, B, C, ..., J are constants. By translation and rotation the equation can be brought into one of two standard forms Ax2 + By2 + Cz2 + J =0 or Ax2 + By2 + Iz =0 In order to sketch the graph of a quadric surface, it is useful to determine the curves of intersection of the surface with planes parallel to the coordinate planes. These curves are called traces of the surface. Ellipsoids The quadric surface with equation x2 y2 z2 + + =1 a2 b2 c2 is called an ellipsoid because all of its traces are ellipses. 2 1 x y 3 2 1 z ±1 ±2 ±3 ±1 ±2 The six intercepts of the ellipsoid are (±a, 0, 0), (0, ±b, 0), and (0, 0, ±c) and the ellipsoid lies in the box |x| ≤ a, |y| ≤ b, |z| ≤ c Since the ellipsoid involves only even powers of x, y, and z, the ellipsoid is symmetric with respect to each coordinate plane. Example 1. Find the traces of the surface 4x2 +9y2 + 36z2 = 36 1 in the planes x = k, y = k, and z = k. Identify the surface and sketch it. Hyperboloids Hyperboloid of one sheet. The quadric surface with equations x2 y2 z2 1. -

Arc Length. Surface Area

Calculus 2 Lia Vas Arc Length. Surface Area. Arc Length. Suppose that y = f(x) is a continuous function with a continuous derivative on [a; b]: The arc length L of f(x) for a ≤ x ≤ b can be obtained by integrating the length element ds from a to b: The length element ds on a sufficiently small interval can be approximated by the hypotenuse of a triangle with sides dx and dy: p Thus ds2 = dx2 + dy2 ) ds = dx2 + dy2 and so s s Z b Z b q Z b dy2 Z b dy2 L = ds = dx2 + dy2 = (1 + )dx2 = (1 + )dx: a a a dx2 a dx2 2 dy2 dy 0 2 Note that dx2 = dx = (y ) : So the formula for the arc length becomes Z b q L = 1 + (y0)2 dx: a Area of a surface of revolution. Suppose that y = f(x) is a continuous function with a continuous derivative on [a; b]: To compute the surface area Sx of the surface obtained by rotating f(x) about x-axis on [a; b]; we can integrate the surface area element dS which can be approximated as the product of the circumference 2πy of the circle with radius y and the height that is given by q the arc length element ds: Since ds is 1 + (y0)2dx; the formula that computes the surface area is Z b q 0 2 Sx = 2πy 1 + (y ) dx: a If y = f(x) is rotated about y-axis on [a; b]; then dS is the product of the circumference 2πx of the circle with radius x and the height that is given by the arc length element ds: Thus, the formula that computes the surface area is Z b q 0 2 Sy = 2πx 1 + (y ) dx: a Practice Problems. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

Section 2.6 Cylindrical and Spherical Coordinates

Section 2.6 Cylindrical and Spherical Coordinates A) Review on the Polar Coordinates The polar coordinate system consists of the origin O,the rotating ray or half line from O with unit tick. A point P in the plane can be uniquely described by its distance to the origin r = dist (P, O) and the angle µ, 0 µ < 2¼ : · Y P(x,y) r θ O X We call (r, µ) the polar coordinate of P. Suppose that P has Cartesian (stan- dard rectangular) coordinate (x, y) .Then the relation between two coordinate systems is displayed through the following conversion formula: x = r cos µ Polar Coord. to Cartesian Coord.: y = r sin µ ½ r = x2 + y2 Cartesian Coord. to Polar Coord.: y tan µ = ( p x 0 µ < ¼ if y > 0, 2¼ µ < ¼ if y 0. · · · Note that function tan µ has period ¼, and the principal value for inverse tangent function is ¼ y ¼ < arctan < . ¡ 2 x 2 1 So the angle should be determined by y arctan , if x > 0 xy 8 arctan + ¼, if x < 0 µ = > ¼ x > > , if x = 0, y > 0 < 2 ¼ , if x = 0, y < 0 > ¡ 2 > > Example 6.1. Fin:>d (a) Cartesian Coord. of P whose Polar Coord. is ¼ 2, , and (b) Polar Coord. of Q whose Cartesian Coord. is ( 1, 1) . 3 ¡ ¡ ³ So´l. (a) ¼ x = 2 cos = 1, 3 ¼ y = 2 sin = p3. 3 (b) r = p1 + 1 = p2 1 ¼ ¼ 5¼ tan µ = ¡ = 1 = µ = or µ = + ¼ = . 1 ) 4 4 4 ¡ 5¼ Since ( 1, 1) is in the third quadrant, we choose µ = so ¡ ¡ 4 5¼ p2, is Polar Coord. -

Area, Volume and Surface Area

The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 11 AREA, VOLUME AND SURFACE AREA A guide for teachers - Years 8–10 June 2011 YEARS 810 Area, Volume and Surface Area (Measurement and Geometry: Module 11) For teachers of Primary and Secondary Mathematics 510 Cover design, Layout design and Typesetting by Claire Ho The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project 2009‑2011 was funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. © The University of Melbourne on behalf of the international Centre of Excellence for Education in Mathematics (ICE‑EM), the education division of the Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute (AMSI), 2010 (except where otherwise indicated). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‑nc‑nd/3.0/ The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 11 AREA, VOLUME AND SURFACE AREA A guide for teachers - Years 8–10 June 2011 Peter Brown Michael Evans David Hunt Janine McIntosh Bill Pender Jacqui Ramagge YEARS 810 {4} A guide for teachers AREA, VOLUME AND SURFACE AREA ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE • Knowledge of the areas of rectangles, triangles, circles and composite figures. • The definitions of a parallelogram and a rhombus. • Familiarity with the basic properties of parallel lines. • Familiarity with the volume of a rectangular prism. • Basic knowledge of congruence and similarity. • Since some formulas will be involved, the students will need some experience with substitution and also with the distributive law. -

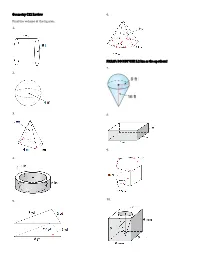

Geometry C12 Review Find the Volume of the Figures. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6

Geometry C12 Review 6. Find the volume of the figures. 1. PREAP: DO NOT USE 5.2 km as the apothem! 7. 2. 3. 8. 9. 4. 10. 5. 11. 16. 17. 12. 18. 13. 14. 19. 15. 20. 21. A sphere has a volume of 7776π in3. What is the radius 33. Two prisms are similar. The ratio of their volumes is of the sphere? 8:27. The surface area of the smaller prism is 72 in2. Find the surface area of the larger prism. 22a. A sphere has a volume of 36π cm3. What is the radius and diameter of the sphere? 22b. A sphere has a volume of 45 ft3. What is the 34. The prisms are similar. approximate radius of the sphere? a. What is the scale factor? 23. The scale factor (ratio of sides) of two similar solids is b. What is the ratio of surface 3:7. What are the ratios of their surface areas and area? volumes? c. What is the ratio of volume? d. Find the volume of the 24. The scale factor of two similar solids is 12:5. What are smaller prism. the ratios of their surface areas and volumes? 35. The prisms are similar. 25. The scale factor of two similar solids is 6:11. What are a. What is the scale factor? the ratios of their surface areas and volumes? b. What is the ratio of surface area? 26. The ratio of the volumes of two similar solids is c. What is the ratio of 343:2197. What is the scale factor (ratio of sides)? volume? d. -

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

Circumference and Area of Circles 353

Circumference and 7-1 Area of Circles MAIN IDEA Find the circumference Measure and record the distance d across the circular and area of circles. part of an object, such as a battery or a can, through its center. New Vocabulary circle Place the object on a piece of paper. Mark the point center where the object touches the paper on both the object radius and on the paper. chord diameter Carefully roll the object so that it makes one complete circumference rotation. Then mark the paper again. pi Finally, measure the distance C between the marks. Math Online glencoe.com • Extra Examples • Personal Tutor • Self-Check Quiz in. 1234 56 1. What distance does C represent? C 2. Find the ratio _ for this object. d 3. Repeat the steps above for at least two other circular objects and compare the ratios of C to d. What do you observe? 4. Graph the data you collected as ordered pairs, (d, C). Then describe the graph. A circle is a set of points in a plane center radius circumference that are the same distance from a (r) (C) given point in the plane, called the center. The segment from the center diameter to any point on the circle is called (d) the radius. A chord is any segment with both endpoints on the circle. The diameter of a circle is twice its radius or d 2r. A diameter is a chord that passes = through the center. It is the longest chord. The distance around the circle is called the circumference. -

Thermodynamics of Spacetime: the Einstein Equation of State

gr-qc/9504004 UMDGR-95-114 Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State Ted Jacobson Department of Physics, University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-4111, USA [email protected] Abstract The Einstein equation is derived from the proportionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat, entropy, and temperature. The key idea is to demand that this relation hold for all the local Rindler causal horizons through each spacetime point, with δQ and T interpreted as the energy flux and Unruh temperature seen by an accelerated observer just inside the horizon. This requires that gravitational lensing by matter energy distorts the causal structure of spacetime in just such a way that the Einstein equation holds. Viewed in this way, the Einstein equation is an equation of state. This perspective suggests that it may be no more appropriate to canonically quantize the Einstein equation than it would be to quantize the wave equation for sound in air. arXiv:gr-qc/9504004v2 6 Jun 1995 The four laws of black hole mechanics, which are analogous to those of thermodynamics, were originally derived from the classical Einstein equation[1]. With the discovery of the quantum Hawking radiation[2], it became clear that the analogy is in fact an identity. How did classical General Relativity know that horizon area would turn out to be a form of entropy, and that surface gravity is a temperature? In this letter I will answer that question by turning the logic around and deriving the Einstein equation from the propor- tionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat Q, entropy S, and temperature T . -

Cones, Pyramids and Spheres

The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 12 CONES, PYRAMIDS AND SPHERES A guide for teachers - Years 9–10 June 2011 YEARS 910 Cones, Pyramids and Spheres (Measurement and Geometry : Module 12) For teachers of Primary and Secondary Mathematics 510 Cover design, Layout design and Typesetting by Claire Ho The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project 2009‑2011 was funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. © The University of Melbourne on behalf of the International Centre of Excellence for Education in Mathematics (ICE‑EM), the education division of the Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute (AMSI), 2010 (except where otherwise indicated). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. 2011. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‑nc‑nd/3.0/ The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 12 CONES, PYRAMIDS AND SPHERES A guide for teachers - Years 9–10 June 2011 Peter Brown Michael Evans David Hunt Janine McIntosh Bill Pender Jacqui Ramagge YEARS 910 {4} A guide for teachers CONES, PYRAMIDS AND SPHERES ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE • Familiarity with calculating the areas of the standard plane figures including circles. • Familiarity with calculating the volume of a prism and a cylinder. • Familiarity with calculating the surface area of a prism. • Facility with visualizing and sketching simple three‑dimensional shapes. • Facility with using Pythagoras’ theorem. • Facility with rounding numbers to a given number of decimal places or significant figures. -

Lateral and Surface Area of Right Prisms 1 Jorge Is Trying to Wrap a Present That Is in a Box Shaped As a Right Prism

CHAPTER 11 You will need Lateral and Surface • a ruler A • a calculator Area of Right Prisms c GOAL Calculate lateral area and surface area of right prisms. Learn about the Math A prism is a polyhedron (solid whose faces are polygons) whose bases are congruent and parallel. When trying to identify a right prism, ask yourself if this solid could have right prism been created by placing many congruent sheets of paper on prism that has bases aligned one above the top of each other. If so, this is a right prism. Some examples other and has lateral of right prisms are shown below. faces that are rectangles Triangular prism Rectangular prism The surface area of a right prism can be calculated using the following formula: SA 5 2B 1 hP, where B is the area of the base, h is the height of the prism, and P is the perimeter of the base. The lateral area of a figure is the area of the non-base faces lateral area only. When a prism has its bases facing up and down, the area of the non-base faces of a figure lateral area is the area of the vertical faces. (For a rectangular prism, any pair of opposite faces can be bases.) The lateral area of a right prism can be calculated by multiplying the perimeter of the base by the height of the prism. This is summarized by the formula: LA 5 hP. Copyright © 2009 by Nelson Education Ltd. Reproduction permitted for classrooms 11A Lateral and Surface Area of Right Prisms 1 Jorge is trying to wrap a present that is in a box shaped as a right prism.