A Comparison of the Metadata Used in Some European Archives with Special Reference to Ottoman Records

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

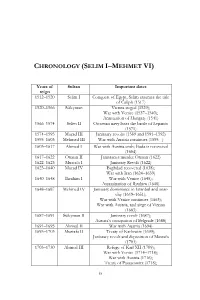

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

The Light Shed by Ruznames on an Ottoman Spectacle of 1740-1750

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (oude _articletitle_deel, vul hierna in): Contemplation or Amusement? _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 22 Artan Chapter 2 Contemplation or Amusement? The Light Shed by Ruznames on an Ottoman Spectacle of 1740-1750 Tülay Artan I have always felt uncomfortable, and if anything recently grown even more uncomfortable, with loose talk of “eighteenth-century Istanbul”. This is a rath- er big block of time in the history of the Ottoman capital that old and new generations of historians have addressed by trying to latch on to themes of administrative change, lifestyles, or the evolution of art and architecture. They have ended up by attributing to it a unified, uniform character which stands in contrast to, and therefore separates it from, the preceding or the following cen- turies. On the one hand there is the triumphant stability of the “classical” age, so-called, and on the other, the Tanzimat’s modernization reforms from the top down. In between, the Ottoman eighteenth century is taken as represent- ing “change”, which, moreover, is said to be especially evident and embodied in the imperial capital. Entertainment, whether in the form of courtly parades or wedding festivals, or the waterfront parties of the royal and sub-royal elite, or popular gatherings revolving around poets or storytellers in public places, plays a particularly strong role in this classification.1 From here the phrase “eighteenth-century Istanbul” takes off into a life of its own. It has, indeed, come to be vested with such authority that, as with any cliché, in many cases it is being used and overused as a substitute for real, em- pirical evidence. -

Political and Economic Transition of Ottoman Sovereignty from a Sole Monarch to Numerous Ottoman Elites, 1683–1750S

Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 70 (1), 49 – 90 (2017) DOI: 10.1556/062.2017.70.1.4 POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC TRANSITION OF OTTOMAN SOVEREIGNTY FROM A SOLE MONARCH TO NUMEROUS OTTOMAN ELITES, 1683–1750S BIROL GÜNDOĞDU Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen Historisches Institut, Osteuropäische Geschichte Otto-Behaghel-Str. 10, Haus D Raum 205, 35394 Gießen, Deutschland e-mail: [email protected] The aim of this paper is to reveal the transformation of the Ottoman Empire following the debacles of the second siege of Vienna in 1683. The failures compelled the Ottoman state to change its socio- economic and political structure. As a result of this transition of the state structure, which brought about a so-called “redistribution of power” in the empire, new Ottoman elites emerged from 1683 until the 1750s. We have divided the above time span into three stages that will greatly help us com- prehend the Ottoman transition from sultanic authority to numerous autonomies of first Muslim, then non-Muslim elites of the Ottoman Empire. During the first period (1683–1699) we see the emergence of Muslim power players at the expense of sultanic authority. In the second stage (1699–1730) we observe the sultans’ unsuccessful attempts to revive their authority. In the third period (1730–1750) we witness the emergence of non-Muslim notables who gradually came into power with the help of both the sultans and external powers. At the end of this last stage, not only did the authority of Ottoman sultans decrease enormously, but a new era evolved where Muslim and non-Muslim leading figures both fought and co-operated with one another for a new distribution of wealth in the Ottoman Empire. -

The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa's Diary

Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.) The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Edited by Richard Wittmann Memoria. Fontes Minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici Pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.): The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak © Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, Bonn 2017 Redaktion: Orient-Institut Istanbul Reihenherausgeber: Richard Wittmann Typeset & Layout: Ioni Laibarös, Berlin Memoria (Print): ISSN 2364-5989 Memoria (Internet): ISSN 2364-5997 Photos on the title page and in the volume are from Regina Salomea Pilsztynowa’s memoir »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (Echo na świat podane procederu podróży i życia mego awantur), compiled in 1760, © Czartoryski Library, Krakow. Editor’s Preface From the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to Istanbul: A female doctor in the eighteenth-century Ottoman capital Diplomatic relations between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Com- monwealth go back to the first quarter of the fifteenth century. While the mutual con- tacts were characterized by exchange and cooperation interrupted by periods of war, particularly in the seventeenth century, the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) marked a new stage in the history of Ottoman-Polish relations. In the light of the common Russian danger Poland made efforts to gain Ottoman political support to secure its integrity. The leading Polish Orientalist Jan Reychman (1910-1975) in his seminal work The Pol- ish Life in Istanbul in the Eighteenth Century (»Życie polskie w Stambule w XVIII wieku«, 1959) argues that the eighteenth century brought to life a Polish community in the Ottoman capital. -

Rebellion, Janissaries and Religion in Sultanic Legitimisation in the Ottoman Empire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Istanbul Bilgi University Library Open Access “THE FURIOUS DOGS OF HELL”: REBELLION, JANISSARIES AND RELIGION IN SULTANIC LEGITIMISATION IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE UMUT DENİZ KIRCA 107671006 İSTANBUL BİLGİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI PROF. DR. SURAIYA FAROQHI 2010 “The Furious Dogs of Hell”: Rebellion, Janissaries and Religion in Sultanic Legitimisation in the Ottoman Empire Umut Deniz Kırca 107671006 Prof. Dr. Suraiya Faroqhi Yard. Doç Dr. M. Erdem Kabadayı Yard. Doç Dr. Meltem Toksöz Tezin Onaylandığı Tarih : 20.09.2010 Toplam Sayfa Sayısı: 139 Anahtar Kelimeler (Türkçe) Anahtar Kelimeler (İngilizce) 1) İsyan 1) Rebellion 2) Meşruiyet 2) Legitimisation 3) Yeniçeriler 3) The Janissaries 4) Din 4) Religion 5) Güç Mücadelesi 5) Power Struggle Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü’nde Tarih Yüksek Lisans derecesi için Umut Deniz Kırca tarafından Mayıs 2010’da teslim edilen tezin özeti. Başlık: “Cehennemin Azgın Köpekleri”: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda İsyan, Yeniçeriler, Din ve Meşruiyet Bu çalışma, on sekizinci yüzyıldan ocağın kaldırılmasına kadar uzanan sürede patlak veren yeniçeri isyanlarının teknik aşamalarını irdelemektedir. Ayrıca, isyancılarla saray arasındaki meşruiyet mücadelesi, çalışmamızın bir diğer konu başlığıdır. Başkentte patlak veren dört büyük isyan bir arada değerlendirilerek, Osmanlı isyanlarının karakteristik özelliklerine ve isyanlarda izlenilen meşruiyet pratiklerine ışık tutulması hedeflenmiştir. Çalışmamızda kullandığımız metot dâhilinde, 1703, 1730, 1807 ve 1826 isyanlarını konu alan yazma eserler karşılaştırılmış, müelliflerin, eserlerini oluşturdukları süreçteki niyetleri ve getirmiş oldukları yorumlara odaklanılmıştır. Argümanların devamlılığını gözlemlemek için, 1703 ve 1730 isyanları ile 1807 ve 1826 isyanları iki ayrı grupta incelenmiştir. 1703 ve 1730 isyanlarının ortak noktası, isyancıların kendi çıkarları doğrultusunda padişaha yakın olan ve rakiplerini bu sayede eleyen politik kişilikleri hedef almalarıdır. -

Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration

Sultan Ahmed III’s calligraphy of the Basmala: “In the Name of God, the All-Merciful, the All-Compassionate” The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration In this work, words in Ottoman Turkish, including the Turkish names of people and their written works, as well as place-names within the boundaries of present-day Turkey, have been transcribed according to official Turkish orthography. Accordingly, c is read as j, ç is ch, and ş is sh. The ğ is silent, but it lengthens the preceding vowel. I is pronounced like the “o” in “atom,” and ö is the same as the German letter in Köln or the French “eu” as in “peu.” Finally, ü is the same as the German letter in Düsseldorf or the French “u” in “lune.” The anglicized forms, however, are used for some well-known Turkish words, such as Turcoman, Seljuk, vizier, sheikh, and pasha as well as place-names, such as Anatolia, Gallipoli, and Rumelia. The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne SALİH GÜLEN Translated by EMRAH ŞAHİN Copyright © 2010 by Blue Dome Press Originally published in Turkish as Tahtın Kudretli Misafirleri: Osmanlı Padişahları 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Published by Blue Dome Press 535 Fifth Avenue, 6th Fl New York, NY, 10017 www.bluedomepress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available ISBN 978-1-935295-04-4 Front cover: An 1867 painting of the Ottoman sultans from Osman Gazi to Sultan Abdülaziz by Stanislaw Chlebowski Front flap: Rosewater flask, encrusted with precious stones Title page: Ottoman Coat of Arms Back flap: Sultan Mehmed IV’s edict on the land grants that were deeded to the mosque erected by the Mother Sultan in Bahçekapı, Istanbul (Bottom: 16th century Ottoman parade helmet, encrusted with gems). -

The Urban Janissary in Eighteenth- Century Istanbul

THE URBAN JANISSARY IN EIGHTEENTH- CENTURY ISTANBUL By GEMMA MASSON A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman And Modern Greek Studies School of History and Cultures University of Birmingham July 2019 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i Abstract The traditional narrative of Ottoman history claims that the Empire went into decline from the seventeenth century onwards, with the eighteenth century being a period of upheaval and change which led to the eventual fall of the Ottomans. The janissaries are major players in these narratives with claims from both secondary and primary writers that this elite military corps became corrupt and this contributed significantly to the overall decline of the Ottoman Empire. Such a simplistic view overlooks the changes taking place in the environment surrounding the janissaries leading to members of the corps needing to adapt to changing circumstances. The result is that the janissaries of this period were for the longest time almost exclusively studied through a binary ‘purity/corruption’ paradigm and it became difficult for scholars to move away from this system of thinking about the corps. -

Legitimizing the Ottoman Sultanate: a Framework for Historical Analysis

LEGITIMIZING THE OTTOMAN SULTANATE: A FRAMEWORK FOR HISTORICAL ANALYSIS Hakan T. K Harvard University Why Ruled by Them? “Why and how,” asks Norbert Elias, introducing his study on the 18th-century French court, “does the right to exercise broad powers, to make decisions about the lives of millions of people, come to reside for years in the hands of one person, and why do those same people persist in their willingness to abide by the decisions made on their behalf?” Given that it is possible to get rid of monarchs by assassination and, in extreme cases, by a change of dynasty, he goes on to wonder why it never occurred to anyone that it might be possible to abandon the existing form of government, namely the monarchy, entirely.1 The answers to Elias’s questions, which pertain to an era when the state’s absolutism was at its peak, can only be found by exposing the relationship between the ruling authority and its subjects. How the subjects came to accept this situation, and why they continued to accede to its existence, are, in essence, the basic questions to be addressed here with respect to the Ottoman state. One could argue that until the 19th century political consciousness had not yet gone through the necessary secularization process in many parts of the world. This is certainly true, but regarding the Ottoman population there is something else to ponder. The Ottoman state was ruled for Most of the ideas I express here are to be found in the introduction to my doc- toral dissertation (Bamberg, 1997) in considering Ottoman state ceremonies in the 19th century. -

The Expansion and Reorganization of the Ottoman Library System: 17544839

THE EXPANSION AND REORGANIZATION OF THE OTTOMAN LIBRARY SYSTEM: 17544839 ~SMA~L E. ERÜNSAL The reign of Mahmud I ( 1730-1754) established the independent library as the norm . The reigns of his five successors, Osman III (1754- 1757), Mustafa III (1757-1774), Abdülhamid I (1774-1789), Selim Il! (1789- 1807) and Mahmud II (1808-1839) , were to see the spread of independent libraries not only in Istanbul but also in the provinces as well. Apart from the libraries he established, Mahmud I, had also begun to build his mosque complex in the well-established tradition of imperial endowment. He chose a site to the south of the Kapallçar~i (covered bazar) which was close to many of the existing colleges. The mosque'is quite unusual for its rococo style and shows definite European influences. But it is most notable for the prominence of the library building, which though part of the complex, was in effect designed to act as an independent library. Many books from the Palace and other sources were designated for this library, and the imperial seal and endowment record of Mahmud I was applied to the fly leaf, indicating that the books had been endowed to the library. Unfortunately, Mahmud I did not live to see the completion of his complex or to give his name to the library which was to surpass all other libraries he had established. When he died in 1754, his brother, Osman III. completed the complex and gaye his name to it. Both the Mosque and the Library are known as the Nur-1 Osmaniye, the light of Osman'. -

The Ottomans in the Early Enlightenment: the Case Of

THE OTTOMANS IN THE EARLY ENLIGHTENMENT: THE CASE OF PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE REIGN OF MAHMUD I (1730-54). by Ahmet Bilaloğlu Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Tolga U. Esmer Second Reader: Prof. Nadia Al-Bagdadi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Statement of Copyright “Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author.” CEU eTD Collection i Abstract The thesis explores cultural politics in the Ottoman Empire from 1718 to 1754 by focusing on the patronage activities of a select group of bureaucrats/intellectuals whose careers spanned the reigns of two early eighteenth-century sultans, Ahmed III (1703-30) and Mahmud I (1730-54). It attempts to locate cultural production in the Ottoman Empire within a broader framework of early modern history and re-evaluate the ideologically-loaded concepts that have marked Ottomanist historiography on the period, such as “the Tulip Age,” “westernization” or “modernization.” In doing so, it attempts to answer some challenging questions such as whether it is purely coincidental that the Ottoman network of actors discussed in this thesis invested tremendous time and material into cultural enterprises such as the introduction of the printing press, establishment a productive paper mill in Yalova and founding of multiple vaḳıf (religious endowment) libraries not only in Istanbul but also in Anatolia and Rumelia at the very same time that their European counterparts engaged in similar types of enterprises that are celebrated in European historiography as the Enlightenment. -

THE NURUOSMANİYE COMPLEX and the WRITING of OTTOMAN ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY (1) Selva SUMAN

THEMETU NURUOSMANIYE JFA 2011/2 COMPLEX DOI:METU 10.4305/METU.JFA.2011.2.7 JFA 2011/2 145 (28:2) 145-166 QUESTIONING AN “ICON OF CHANGE”: THE NURUOSMANİYE COMPLEX AND THE WRITING OF OTTOMAN ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY (1) Selva SUMAN Received: 13.05.2011, Final Text: 12.10.2011 INTRODUCTION Keywords: the Nuruosmaniye Complex; Târih-i Câmi‘i Şerif-i Nûr-i ‘Osmânî; The eighteenth century began with the return of the court to İstanbul after Mahmud I; Eighteenth Century Ottoman the Edirne incident (1703) and some profound changes that took place in Architecture; Ottoman Baroque. the political, economic, social, and cultural spheres . In the meantime, the 1. This paper developed from my M.A. Ottoman capital set the stage for an intensive architectural campaign; there Thesis presented to the Institute of Social Sciences at Boğaziçi University (Suman, was an upsurge in renovation, restoration, and building activities mainly 2007). I am grateful to my advisor Associate for the purpose of reaffirming state presence and authority in İstanbul. Prof. Ahmet Ersoy and Associate Prof. Çiğdem Kafescioğlu for their encouraging These urban and architectural developments concomitant with the ongoing remarks and continuous support. I am social transformations changed the built environment of the city, new thankful to late Prof. Günhan Danışman for his guidance. All photographs by the author, building types emerged and there was an infiltration of foreign elements unless otherwise stated. from outside cultures that was made visible in the gradual penetration 2. Hamadeh notes that what happened in the of western neoclassical, baroque, and rococo forms. Hence a totally new eighteenth century was in fact a changing architectural idiom started to appear in İstanbul, marked by the hybridity disposition toward tradition and innovation. -

Ottoman Expressions of Early Modernity and the "Inevitable"

Ottoman Expressions of Early Modernity and the "Inevitable" Question of Westernization Author(s): Shirine Hamadeh Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 63, No. 1 (Mar., 2004), pp. 32- 51 Published by: Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4127991 Accessed: 19/04/2010 03:03 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sah. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. http://www.jstor.org Ottoman Expressions of Early Modernity and the "Inevitable" Question of Westernization SHIRINE HAMADEH Rice University he conspicuousappearance, in 1793, of the Neither its design nor its new colors and novel ornaments have princely pavilion of Negatabad on the shores of ever been witnessed by either Mani or even Behzad.3 the Bosphorus in Istanbul captured the attention of many contemporary observers (Figure 1).