Ottoman Expressions of Early Modernity and the "Inevitable"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

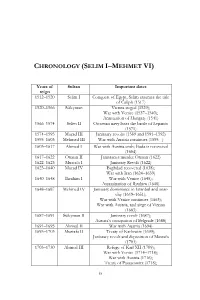

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

Estambul Y Sus Revoluciones: Camino Hacia La Modernidad

Estambul y sus revoluciones: camino hacia la modernidad Frédéric Hitzel* i hoy me toca a mí, mañana te tocará a ti”. Esta advertencia, que es “Sfrecuente encontrar grabada en los epitafios de las estelas funerarias otomanas, recuerda al buen musulmán que todos los hombres están desti nados a morir, en un tiempo límite fijado por Dios. Este término predes tinado no puede adelantarse ni atrasarse, tal como lo dice otra fórmula funeraria común en los cementerios de Estambul: “Puesto que le llegó su fin, no podría haber piedad para él”. Este precepto se aplica a todo ser humano, incluso a los sultanes otomanos que, desde su capital de Estambul, gobier nan el más vasto imperio musulmán, que se extiende desde las riberas del Adriático hasta los confines de África del Norte (excepto Marruecos), pa sando por la península arábiga. Sin embargo, es obvio: el soberano otomán no era el primer fiel que llegaba. Era la sombra de Dios en la Tierra, lo que hacía de él una pieza esencial del sistema institucional. Su muerte plantea ba la delicada cuestión de su sucesión. Si bien la mayoría de los sultanes murieron en el trono, algunos fueron depuestos, y otros asesinados. Esto es lo que ocurrió al sultán Selim III, quien tuvo que ceder el trono a su primo Mustafá IV en 1807, antes de ser salvajemente ejecutado el año siguiente. El trágico final de su reinado, sobre el que volveremos más adelante, marcó fuertemente la historiografía turca. En efecto, más que cualquier otro sul tán antes que él, Selim III fue testimonio de una voluntad de renovación del Estado otomano, que hizo de él el verdadero precursor de los sultanes y * Traducción del francés de Arturo Vázquez Barrón. -

The Armenian Robert L

JULY 26, 2014 MirTHErARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXV, NO. 2, Issue 4345 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 Armenia Inaugurates AREAL Linear Christians Flee Mosul en Masse Accelerator BAGHDAD (AP) — The message played array of other Sunni militants captured the a mobile number just in case we are offend - YEREVAN (Public Radio of Armenia) — The over loudspeakers gave the Christians of city on June 10 — the opening move in the ed by anybody,” Sahir Yahya, a Christian Advanced Research Electron Accelerator Iraq’s second-largest city until midday insurgents’ blitz across northern and west - and government employee from Mosul, said Laboratory (AREAL) linear accelerator was inau - Saturday to make a choice: convert to ern Iraq. As a religious minority, Christians Saturday. “This changed two days ago. The gurated this week at the Center for Islam, pay a tax or face death. were wary of how they would be treated by Islamic State people revealed their true sav - the Advancement of Natural Discoveries By the time the deadline imposed by the hardline Islamic militants. age nature and intention.” using Light Emission (CANDLE) Synchrotron Islamic State extremist group expired, the Yahya fled with her husband and two Research Institute in Yerevan. vast majority of Christians in Mosul had sons on Friday morning to the town of The modern accelerator is an exceptional and made their decision. They fled. Qaraqoush, where they have found tempo - huge asset, CANDLE’s Executive Director Vasily They clambered into cars — children, par - Most of Mosul’s remaining Christians rary lodging at a monastery. -

Eighteenth-Century Ottoman Princesses As Collectors Chinese and European Porcelains in the Topkapı Palace Museum

AO39_r1 10.06.10 imAges are fOr pOsitiOn only; pAge numbers nOt firm tülay artan eighteenth-century ottoman princesses as collectors Chinese and European Porcelains in the Topkapı Palace Museum Abstract Ceramic collecting by women has been interpreted as a form of social competition and conspicuous consumption. But collecting differs from conspicuous consump- tion, which involves purchasing goods or services not because they are needed, but because there is status and prestige in being seen to have them, and even in wasting them. Collecting, in contrast, implies conservation and augmentation, the preser- vation of history, aesthetic or scholarly interest, love of beauty, a form of play, differ- ent varieties of fetishism, the excitement of the hunt, investment, and even support of a particular industry or artist. None of these motives, however, readily explains the activities of Ottoman collector-princesses in the eighteenth century—which are all the more mysterious because these women remain relatively anonymous as individuals. It is not easy for us to elucidate the reasons (other than conspicuous consumption) for their amass- ing of porcelain, and of European porcelain in particular. Could the collection and display of ceramics have been a way of actively creating meanings for themselves and others? Do the collecting habits of these princesses shed some light on their personalities and aspirations? By focusing on two among them I will argue that collecting European rather than Chinese porcelain did signify a notable change of attitude -

The Light Shed by Ruznames on an Ottoman Spectacle of 1740-1750

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (oude _articletitle_deel, vul hierna in): Contemplation or Amusement? _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 22 Artan Chapter 2 Contemplation or Amusement? The Light Shed by Ruznames on an Ottoman Spectacle of 1740-1750 Tülay Artan I have always felt uncomfortable, and if anything recently grown even more uncomfortable, with loose talk of “eighteenth-century Istanbul”. This is a rath- er big block of time in the history of the Ottoman capital that old and new generations of historians have addressed by trying to latch on to themes of administrative change, lifestyles, or the evolution of art and architecture. They have ended up by attributing to it a unified, uniform character which stands in contrast to, and therefore separates it from, the preceding or the following cen- turies. On the one hand there is the triumphant stability of the “classical” age, so-called, and on the other, the Tanzimat’s modernization reforms from the top down. In between, the Ottoman eighteenth century is taken as represent- ing “change”, which, moreover, is said to be especially evident and embodied in the imperial capital. Entertainment, whether in the form of courtly parades or wedding festivals, or the waterfront parties of the royal and sub-royal elite, or popular gatherings revolving around poets or storytellers in public places, plays a particularly strong role in this classification.1 From here the phrase “eighteenth-century Istanbul” takes off into a life of its own. It has, indeed, come to be vested with such authority that, as with any cliché, in many cases it is being used and overused as a substitute for real, em- pirical evidence. -

Political and Economic Transition of Ottoman Sovereignty from a Sole Monarch to Numerous Ottoman Elites, 1683–1750S

Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 70 (1), 49 – 90 (2017) DOI: 10.1556/062.2017.70.1.4 POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC TRANSITION OF OTTOMAN SOVEREIGNTY FROM A SOLE MONARCH TO NUMEROUS OTTOMAN ELITES, 1683–1750S BIROL GÜNDOĞDU Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen Historisches Institut, Osteuropäische Geschichte Otto-Behaghel-Str. 10, Haus D Raum 205, 35394 Gießen, Deutschland e-mail: [email protected] The aim of this paper is to reveal the transformation of the Ottoman Empire following the debacles of the second siege of Vienna in 1683. The failures compelled the Ottoman state to change its socio- economic and political structure. As a result of this transition of the state structure, which brought about a so-called “redistribution of power” in the empire, new Ottoman elites emerged from 1683 until the 1750s. We have divided the above time span into three stages that will greatly help us com- prehend the Ottoman transition from sultanic authority to numerous autonomies of first Muslim, then non-Muslim elites of the Ottoman Empire. During the first period (1683–1699) we see the emergence of Muslim power players at the expense of sultanic authority. In the second stage (1699–1730) we observe the sultans’ unsuccessful attempts to revive their authority. In the third period (1730–1750) we witness the emergence of non-Muslim notables who gradually came into power with the help of both the sultans and external powers. At the end of this last stage, not only did the authority of Ottoman sultans decrease enormously, but a new era evolved where Muslim and non-Muslim leading figures both fought and co-operated with one another for a new distribution of wealth in the Ottoman Empire. -

The Socio-Spatial Transformation of Beyazit Square

THE SOCİO-SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION OF BEYAZIT SQUARE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES OF İSTANBUL ŞEHİR UNIVERSITY BY BÜŞRA PARÇA KÜÇÜKGÖZ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN SOCIOLOGY FEBRUARY 2018 ABSTRACT THE SOCIO-SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION OF BEYAZIT SQUARE Küçükgöz Parça, Büşra. MA in Sociology Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Eda Ünlü Yücesoy February 2018, 136 Pages In this study, I elaborated formation and transformation of the Beyazıt Square witnessed in modernization process of Turkey. Throughout the research, I examine thematically the impacts of socio-political breaks the on shaping of Beyazıt Square since the 19th century. According to Lefebvre's theory of the spatial triad, which is conceptualized as perceived space, conceived space and lived space, I focus on how Beyazıt Square is imagined and reproduced and how it corresponds to unclear everyday life. I also discuss the creation of ideal public space and society as connected with the arrangement of Beyazit Square. In this thesis, I tried to discuss the Beyazıt Square which has a significant place in social history in the light of an image of “ideal public space or square". Keywords: Beyazıt Square, Public Space, Conceived Space, Lived Space, Lefebvre, Production of Space. iv ÖZ BEYAZIT MEYDANI’NIN SOSYO-MEKANSAL DÖNÜŞÜMÜ Küçükgöz Parça, Büşra. Sosyoloji Yüksek Lisans Programı Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Dr. Eda Ünlü Yücesoy Şubat 2018, 136 Sayfa Bu çalışmada, Türkiye'nin modernleşme sürecine tanıklık eden Beyazıt Meydanı'nın oluşum ve dönüşümünü araştırdım. Araştırma boyunca özellikle sosyo-politik kırılmaların Beyazıt Meydanı'nın şekillenmesinde ne tür etkiler yarattığını 19. -

Sabiha Gökçen's 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO ―Sabiha Gökçen‘s 80-Year-Old Secret‖: Kemalist Nation Formation and the Ottoman Armenians A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Fatma Ulgen Committee in charge: Professor Robert Horwitz, Chair Professor Ivan Evans Professor Gary Fields Professor Daniel Hallin Professor Hasan Kayalı Copyright Fatma Ulgen, 2010 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Fatma Ulgen is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For my mother and father, without whom there would be no life, no love, no light, and for Hrant Dink (15 September 1954 - 19 January 2007 iv EPIGRAPH ―In the summertime, we would go on the roof…Sit there and look at the stars…You could reach the stars there…Over here, you can‘t.‖ Haydanus Peterson, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, reminiscing about the old country [Moush, Turkey] in Fresno, California 72 years later. Courtesy of the Zoryan Institute Oral History Archive v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………….... -

Turkish Plastic Arts

Turkish Plastic Arts by Ayla ERSOY REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM PUBLICATIONS © Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism General Directorate of Libraries and Publications 3162 Handbook Series 3 ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 www.kulturturizm.gov.tr e-mail: [email protected] Ersoy, Ayla Turkish plastic arts / Ayla Ersoy.- Second Ed. Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2009. 200 p.: col. ill.; 20 cm.- (Ministry of Culture and Tourism Publications; 3162.Handbook Series of General Directorate of Libraries and Publications: 3) ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 I. title. II. Series. 730,09561 Cover Picture Hoca Ali Rıza, İstambol voyage with boat Printed by Fersa Ofset Baskı Tesisleri Tel: 0 312 386 17 00 Fax: 0 312 386 17 04 www.fersaofset.com First Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2008. Second Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2009. *Ayla Ersoy is professor at Dogus University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Design. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 Sources of Turkish Plastic Arts 5 Westernization Efforts 10 Sultans’ Interest in Arts in the Westernization Period 14 I ART OF PAINTING 18 The Primitives 18 Painters with Military Background 20 Ottoman Art Milieu in the Beginning of the 20th Century. 31 1914 Generation 37 Galatasaray Exhibitions 42 Şişli Atelier 43 The First Decade of the Republic 44 Independent Painters and Sculptors Association 48 The Group “D” 59 The Newcomers Group 74 The Tens Group 79 Towards Abstract Art 88 Calligraphy-Originated Painters 90 Artists of Geometrical Non-Figurative -

The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa's Diary

Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.) The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Edited by Richard Wittmann Memoria. Fontes Minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici Pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.): The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak © Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, Bonn 2017 Redaktion: Orient-Institut Istanbul Reihenherausgeber: Richard Wittmann Typeset & Layout: Ioni Laibarös, Berlin Memoria (Print): ISSN 2364-5989 Memoria (Internet): ISSN 2364-5997 Photos on the title page and in the volume are from Regina Salomea Pilsztynowa’s memoir »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (Echo na świat podane procederu podróży i życia mego awantur), compiled in 1760, © Czartoryski Library, Krakow. Editor’s Preface From the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to Istanbul: A female doctor in the eighteenth-century Ottoman capital Diplomatic relations between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Com- monwealth go back to the first quarter of the fifteenth century. While the mutual con- tacts were characterized by exchange and cooperation interrupted by periods of war, particularly in the seventeenth century, the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) marked a new stage in the history of Ottoman-Polish relations. In the light of the common Russian danger Poland made efforts to gain Ottoman political support to secure its integrity. The leading Polish Orientalist Jan Reychman (1910-1975) in his seminal work The Pol- ish Life in Istanbul in the Eighteenth Century (»Życie polskie w Stambule w XVIII wieku«, 1959) argues that the eighteenth century brought to life a Polish community in the Ottoman capital. -

Joys of the East TEFAF Online Running from November 1-4 with Preview Days on October 30 and 31

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp ISSUE 2463 | antiquestradegazette.com | 17 October 2020 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 koopman rare art antiques trade KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Main picture: Jagat Singh II (1734-51) enjoying TEFAF moves a dance performance (detail) painted in Udaipur, c.1740. From Francesca Galloway. to summer Below: a 19th century Qajar gold and silver slot for 2021 inlaid steel vase. From Oliver Forge and Brendan Lynch. The TEFAF Maastricht fair has been delayed to May 31-June 6, 2021. It is usually held in March but because of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic the scheduled dates have been moved, with the preview now to be held on May 29-30. The decision to delay was taken by the executive committee of The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF). Chairman Hidde van Seggelen said: “It is our hope that by pushing the dates of TEFAF Maastricht to later in the spring, we make physical attendance possible, safe, and comfortable for our exhibitors and guests.” Meanwhile, TEFAF has launched a digital marketplace for dealers with the first Joys of the East TEFAF Online running from November 1-4 with preview days on October 30 and 31. Two-part Asian Art in London begins with Indian and Islamic art auctions and dealer exhibitions Aston’s premises go This year’s ‘Islamic Week’, running from 29-November 7. -

Arab Scholars and Ottoman Sunnitization in the Sixteenth Century 31 Helen Pfeifer

Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 Islamic History and Civilization Studies and Texts Editorial Board Hinrich Biesterfeldt Sebastian Günther Honorary Editor Wadad Kadi volume 177 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ihc Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 Edited by Tijana Krstić Derin Terzioğlu LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “The Great Abu Sa’ud [Şeyhü’l-islām Ebū’s-suʿūd Efendi] Teaching Law,” Folio from a dīvān of Maḥmūd ‘Abd-al Bāqī (1526/7–1600), The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The image is available in Open Access at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/447807 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Krstić, Tijana, editor. | Terzioğlu, Derin, 1969- editor. Title: Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 / edited by Tijana Krstić, Derin Terzioğlu. Description: Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Islamic history and civilization. studies and texts, 0929-2403 ; 177 | Includes bibliographical references and index.