Indian Muslims the Ottoman Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

The Battle for Bahrain Continues

INSS Insight No. 329, April 25, 2012 The Battle for Bahrain Continues Yoel Guzansky More than a year after the "Arab spring" came to Bahrain, the fire has still not died down. Although recent days were essentially no different from those that preceded it, the Formula One Grand Prix held in the kingdom brought the uprising back to the headlines, with the royal family seeking to use the race to demonstrate business as usual, and the Shiite opposition exploiting it to win people over to its cause. The popular uprising in Bahrain began soon after the start of the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, but in recent months, as a result of events in Syria, media attention has turned elsewhere. Meantime, however, the protest of the Shiite majority – estimated to constitute some 70 percent of the population – against the Sunni royal family has continued on a low flame. Demonstrations take place every week, generally in Shiite villages outside the capital, Manama, and not infrequently, they deteriorate into serious violence. Thus far, the regime has acknowledged the deaths of twenty people, while the opposition claims that eighty have been killed. Bahrain’s territory is 760 square kilometers. Its neighbor Qatar is located to the southeast, while Saudi Arabia, connected to Bahrain via the King Fahd Bridge built in the mid 1980s, is to the west. Bahrain’s population is slightly over 1 million, about half of whom are foreign workers. Bahrain was the first state in the Gulf to discover oil, but because of the depletion of its reserves over the years, its main revenues come from profits from a Saudi oil field and its role as a banking and commercial center. -

Himachal Karam Singh H

Scholarship Sanctioned during 2009-10 under the Scheme Merit-Cum-Means, Post Matric & Pre- Matric Scholarship to the candidates belonging to Minority Communities (1) List of 33 Students to whom Scholarship Sanctioned under Merit-Cum- Means Scholarship. Sl. Name of student Name & address ot Course Amount of scholarship (in Bank No. the institution in Rs.) Draft Date favour of draft to be No. made Maintenance Course Total Allowance Fee Abida Shah D/o 2784448 24-5-10 Registrar, Institutes Sh. Abdul Gani of Management 1 Shah H. No. 24/15 MBA 5000 20000 25000 Studies HP Lowere Bazar University Shimla-5 Shimla Heena Naz D/o 174326 24-5-10 Principal IITT Sh. Mohd. Shakeel College of 2 H. No. 252 Ward B.Tech. 5000 20000 25000 Engineering Kala No. 1Charzan Amb Sirmour Street Nahan Rukhsar D/o Sh. Principal Mata Bala 174327 24-5-10 Sabir Ali H. No. Sundri College of 3 LLB 5000 20000 25000 269/9 Katcha Legal Studeis Shimla Tank Nahan Road Nahan Aman S/o Sh. 174328 24-5-10 Principal IITT Abdul Latif H. No. College of 4 3177/12 Katcha B.Tech. 5000 20000 25000 Engineering Kala Tank Nahan Distt Amb Sirmour Sirmour Israna D/o Sh. Principal Himalyan 174329 24-5-10 Nazim Ali Vill Group of 5 Toka PO Professioinal Institute M.B.A. 5000 20000 25000 Jamniwala Distt. Kala Amb Distt Sirmour Sirmour Talib Hussain S/o 174330 24-5-10 Sh. Hashim Ali Principal Jawaharlal Mand Miani PO Nehru Government 6 B.Tech. 5000 20000 25000 Mand Manjwa Engineering College Indora Kangra - Sundernagar Mandi 176403 Israil S/o Sh. -

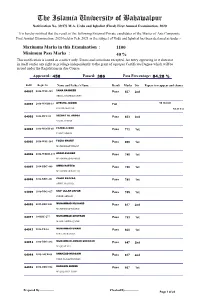

M.A Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final)

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Notification No. 39/CS M.A. Urdu and Iqbaliat (Final) First Annual Examination, 2020 It is hereby notified that the result of the following External/Private candidates of the Master of Arts Composite First Annual Examination, 2020 held in Feb, 2021 in the subject of Urdu and Iqbaliat has been declared as under:- Maximum Marks in this Examination : 1100 Minimum Pass Marks : 40 % This notification is issued as a notice only. Errors and omissions excepted. An entry appearing in it does not in itself confer any right or privilege independently to the grant of a proper Certificate/Degree which will be issued under the Regulations in due Course. -5E -4E Appeared: 458 Passed: 386 Pass Percentage: 84.28 % Roll# Regd. No Name and Father's Name Result Marks Div Papers to reappear and chance 64001 2016-WST-348 SANA RASHEED Pass 637 2nd ABDUL RASHEED KHAN VII IX X XI 64002 2016-WNDR-19 AYESHA JAVAID Fail JAVAID AKHTAR R/A till S-22 64003 2014-IWY-88 SEERAT UL AROOJ Pass 653 2nd NASIR AHMAD 64004 2016-MOCB-05 FAZEELA BIBI Pass 712 1st JAM GAMMON 64005 2016-WST-164 FOZIA SHARIF Pass 690 1st MUHAMMAD SHARIF 64006 2016-WBDR-173 ANAM ASGHAR Pass 740 1st MUHAMMAD ASGHAR 64007 2018-BDC-440 AMNA RAFEEQ Pass 730 1st MUHAMMAD RAFEEQ 64008 2016-BDC-481 ZAHID RAZZAQ Pass 741 1st ABDUL RAZZAQ 64009 2016-BDC-427 SAIF ULLAH ZAFAR Pass 745 1st ZAFAR AHMAD 64010 2015-BDC-623 MUHAMMAD MUJAHID Pass 617 2nd MUHAMMAD AKRAM 64011 10-BDC-277 MUHAMMAD GHUFRAN Pass 753 1st MALIK ABDUL QADIR 64012 2016-US-16 MUHAMMAD UMAIR Pass 660 1st GHULAM RASOOL 64013 2016-BDC-434 MUHAMMAD AHMAD SHEHZAD Pass 647 2nd LIAQUAT ALI 64014 2015-AICB-08 SHAHZAD HUSSAIN Pass 617 2nd SYED SAJJAD HUSSAIN 64015 2016-BDC-542 HASNAIN AHMED Pass 667 1st MULAZIM HUSSAIN Prepared By--------------- Checked By-------------- Page 1 of 24 Roll# Regd. -

Detail of Registered Travel Agents in Jalandhar District Sr.No

Detail of Registered Travel Agents in Jalandhar District Sr.No. Licence No. Name of Travel Agent Office Name & Address Home Address Licence Type Licence Issue Date Till Which date Photo Licence is Valid 1 2 3 4 5 1 1/MC1/MA Sahil Bhatia S/o Sh. M/s Om Visa, Shop R/o H.No. 57, Park Avenue, Travel Agency Consultancy Ticekting Agent 9/4/2015 9/3/2020 Manoj Bhatia No.10, 12, AGI Business Ladhewali Road, Jalandhar Centre, Near BMC Chowk, Garha Road, Jalandhar 2 2/MC1/MA Mr. Bhavnoor Singh Bedi M/s Pyramid E-Services R/o H.No.127, GTB Avenue, Jalandhar Travel Agent Coaching Consultancy Ticekting Agent 9/10/2015 9/9/2020 S/o Mr. Jatinder Singh Pvt. Ltd., 6A, Near Old Institution of Bedi Agriculture Office, Garha IELTS Road, Jalandhar 3 3/MC1/MA Mr.Kamalpreet Singh M/S CWC Immigration Sco 26, Ist to 2nd Floor Crystal Plaza, Travel Agency 12/21/2015 12/20/2020 Khaira S/o Mr. Kar Solution Choti Baradari Pase-1 Garha Road , Jalandhar 4 4/MC1/MA Sh. Rahul Banga S/o Late M/S Shony Travels, 2nd R/o 133, Tower Enclave, Phase-1, Travel Agent Ticketing Agent 12/21/2015 6/17/2023 Sh. Durga Dass Bhanga Floor, 190-L, Model Jalandhar Town Market, Jalandhar 5 5/MC1/MA Sh.Jaspla Singh S/o Sh. M/S Cann. World Sco-307, 2nd Floor, Prege Chamber , Travel Agency 2/3/2016 2/2/2021 Mohan Singh Consulbouds opp. Nanrinder Cinema Jalandhar 6 6/MC1/MA Sh. -

Duke University Dissertation Template

A Sea of Debt: Histories of Commerce and Obligation in the Indian Ocean, c. 1850-1940 by Fahad Ahmad Bishara Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Timur Kuran ___________________________ Bruce S. Hall ___________________________ Jonathan K. Ocko Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 i v ABSTRACT A Sea of Debt: Histories of Commerce and Obligation in the Indian Ocean, c. 1850-1940 by Fahad Ahmad Bishara Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Edward J. Balleisen, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Co-supervisor ___________________________ Janet J. Ewald ___________________________ Timur Kuran ___________________________ Bruce S. Hall ___________________________ Jonathan K. Ocko An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Fahad Ahmad Bishara 2012 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a legal history of debt and economic life in the Indian Ocean during the nineteenth and early-twentieth century. It draws on materials from Bahrain, Muscat, Bombay, Zanzibar and London to examine how members of an ocean-wide commercial society constructed relationships of economic mutualism with one another by mobilizing debt and credit. It further explores how they expressed their debt relationships through legal idioms, and how they mobilized commercial and legal instruments to adapt to the emergence of modern capitalism in the region. -

The Light Shed by Ruznames on an Ottoman Spectacle of 1740-1750

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (oude _articletitle_deel, vul hierna in): Contemplation or Amusement? _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 22 Artan Chapter 2 Contemplation or Amusement? The Light Shed by Ruznames on an Ottoman Spectacle of 1740-1750 Tülay Artan I have always felt uncomfortable, and if anything recently grown even more uncomfortable, with loose talk of “eighteenth-century Istanbul”. This is a rath- er big block of time in the history of the Ottoman capital that old and new generations of historians have addressed by trying to latch on to themes of administrative change, lifestyles, or the evolution of art and architecture. They have ended up by attributing to it a unified, uniform character which stands in contrast to, and therefore separates it from, the preceding or the following cen- turies. On the one hand there is the triumphant stability of the “classical” age, so-called, and on the other, the Tanzimat’s modernization reforms from the top down. In between, the Ottoman eighteenth century is taken as represent- ing “change”, which, moreover, is said to be especially evident and embodied in the imperial capital. Entertainment, whether in the form of courtly parades or wedding festivals, or the waterfront parties of the royal and sub-royal elite, or popular gatherings revolving around poets or storytellers in public places, plays a particularly strong role in this classification.1 From here the phrase “eighteenth-century Istanbul” takes off into a life of its own. It has, indeed, come to be vested with such authority that, as with any cliché, in many cases it is being used and overused as a substitute for real, em- pirical evidence. -

The Khilafat Movement in India 1919-1924

THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR T AAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 62 THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 A. C. NIEMEIJER THE HAGUE - MAR TINUS NIJHOFF 1972 I.S.B.N.90.247.1334.X PREFACE The first incentive to write this book originated from a post-graduate course in Asian history which the University of Amsterdam organized in 1966. I am happy to acknowledge that the university where I received my training in the period from 1933 to 1940 also provided the stimulus for its final completion. I am greatly indebted to the personal interest taken in my studies by professor Dr. W. F. Wertheim and Dr. J. M. Pluvier. Without their encouragement, their critical observations and their advice the result would certainly have been of less value than it may be now. The same applies to Mrs. Dr. S. C. L. Vreede-de Stuers, who was prevented only by ill-health from playing a more active role in the last phase of preparation of this thesis. I am also grateful to professor Dr. G. F. Pijper who was kind enough to read the second chapter of my book and gave me valuable advice. Beside this personal and scholarly help I am indebted for assistance of a more technical character to the staff of the India Office Library and the India Office Records, and also to the staff of the Public Record Office, who were invariably kind and helpful in guiding a foreigner through the intricacies of their libraries and archives. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

How History Matters for Student Performance. Lessons from the Partitions of Poland Ú Job Market Paper Latest Version: HERE

How History Matters for Student Performance. Lessons from the Partitions of Poland ú Job Market Paper Latest Version: HERE. Pawe≥Bukowski † This paper examines the effect on current student performance of the 19th century Partitions of Poland among Austria, Prussia and Russia. Despite the modern similarities of the three regions, using a regression discontinuity design I show that student test scores are 0.6 standard deviation higher on the Austrian side of the former Austrian-Russian border. This magnitude is comparable to the black vs. white test score gap in the US. On the other hand, I do not find evidence for differences on the Prussian-Russian border. Using a theoretical model and indirect evidence I argue that the Partitions have persisted through their impact on social norms toward local schools. Nevertheless, the persistent effect of Austria is puzzling given the histori- cal similarities of the Austrian and Prussian educational systems. I argue that the differential legacy of Austria and Prussia originates from the Aus- trian Empire’s policy to promote Polish identity in schools and the Prussian Empire’s efforts to Germanize the Poles through education. JEL Classification: N30, I20, O15, J24 úI thank Sascha O. Becker, Volha Charnysh, Gregory Clark, Tomas Cvrcek, John S. Earle, Irena Grosfeld, Hedvig Horvát, Gábor Kézdi, Jacek Kochanowicz, Attila Lindner, Christina Romer, Ruth M. Schüler, Tamás Vonyó, Jacob Weisdorf, Agnieszka WysokiÒska, Noam Yuchtman, the partici- pants of seminars at Central European University, University of California at Berkeley, University of California at Davis, Warsaw School of Economics, Ifo Center for the Economics of Education and FRESH workshops in Warsaw and Canterbury, WEast workshop in Belgrade, European Historical Economics Society Summer School in Berlin for their comments and suggestions. -

St. Teresa's School

ST. TERESA’S SCHOOL st 1 Raj. Girls Battalion NCC NAME: AVANI SHEKHAWAT FATHER’s NAME: MR. BHAWANI SINGH SHEKHAWAT RANK: CADET CLASS: IX PROFESSTION: STUDENT TOPIC: WARTIME GALLENTRY AWARD ‘PARAM VEER CHAKRA’ WINNERS PARAM VEER CHAKRA India's highest military adornment, after Bharat Ratna which is awarded to those courageous and daring or the braves ,who self-sacrifice their life for their motherland, while fighting with enemy, whether on land, at sea or in the air. Param Veer Chakra cannot be asked, it need to be earnrd. This award comes to those ,if death strikes before them, they prove their blood, they swear, they can kill death. It was introduced on 26 January, 1950 on the first Republic Day. This award may be given posthumously. The medal of the PVC was designed by Savitri Khanolkar. The list of 21 Brave Military Men who have received this award to date are: 1. Maj. Somnath Sharma 4 Kumaon|Badgam, Kashmir|November 3, 1947 Major Sharma, with a broken arm, staved off enemy attacking on Badgam aerodrome and Srinagar. He was personally filling magazines and issuing them to the light machine gunners. His death inspired the fellow soldiers to fight the enemy 7:1 for six hours. 2. Naik Jadunath Singh 1 Rajput|Taindhara, Naushera, Kashmir| February 6, 1948 Naik Singh was commanding a forward post when the enemy attacked. We suffered heavy losses. Eventually Singh somehow saved his troops, but fell to bullets. 3. 2nd Lt Rama Raghoba Rane Bombay Engineers|Naushera-Rajouri Road|April 8-11, 1948 Rane braved machine gun fire, cleared mines and roadblocks as he laid a path for tanks.