1 Hansen & Quinn – Notes on Accentuation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Third Declension, That Is, Consonant-Stem Nouns; Patterns I

Chapter 7: Third-Declension Nouns Chapter 7 covers the following: third declension, that is, consonant-stem nouns; patterns in the formation of the nominative singular of third declension; and the agreement between third- declension nouns and first/second-declension adjectives. At the end of the lesson, we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There is only one important rule to remember here: the genitive singular ending in third declension is -is . We’ve already encountered first- and second-declension nouns. Now we’ll address the third. A fair question to ask, and one which some of you may be asking, is why is there a third declension at all? Third declension is Latin’s “catch-all” category for nouns. Into it have been put all nouns whose bases end with consonants ─ any consonant! That makes third declension very different from first and second declension. First declension, as you’ll remember, is dominated by a-stem nouns like femina and cura . Second declension is dominated by o- or u-stem nouns like amicus or oculus . Those vowels give those declensions a certain consistency, but the same is not true of third declension where one form, the nominative singular, is affected by the fact that its ending -s runs into the wide variety of consonants found at the ends of the bases of third-declension nouns, and the collision of those consonants causes irregular forms to appear in the nominative singular. That’s the bad news. The good news is that only one case and number is affected by this, the nominative singular. -

“The Role of Specific Grammar for Interpretation in Sanskrit”

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 2 (2021)pp: 107-187 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper “The Role of Specific Grammar for Interpretation in Sanskrit” Dr. Shibashis Chakraborty Sact-I Depatment of Sanskrit, Panskura Banamali College Wb, India. Abstract: Sanskrit enjoys a place of pride among Indian languages in terms of technology solutions that are available for it within India and abroad. The Indian government through its various agencies has been heavily funding other Indian languages for technology development but the funding for Sanskrit has been slow for a variety of reasons. Despite that, the work in the field has not suffered. The following sections do a survey of the language technology R&D in Sanskrit and other Indian languages. The word `Sanskrit’ means “prepared, pure, refined or prefect”. It was not for nothing that it was called the `devavani’ (language of the Gods). It has an outstanding place in our culture and indeed was recognized as a language of rare sublimity by the whole world. Sanskrit was the language of our philosophers, our scientists, our mathematicians, our poets and playwrights, our grammarians, our jurists, etc. In grammar, Panini and Patanjali (authors of Ashtadhyayi and the Mahabhashya) have no equals in the world; in astronomy and mathematics the works of Aryabhatta, Brahmagupta and Bhaskar opened up new frontiers for mankind, as did the works of Charak and Sushrut in medicine. In philosophy Gautam (founder of the Nyaya system), Ashvaghosha (author of Buddha Charita), Kapila (founder of the Sankhya system), Shankaracharya, Brihaspati, etc., present the widest range of philosophical systems the world has ever seen, from deeply religious to strongly atheistic. -

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

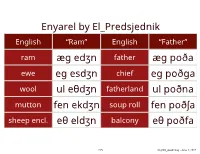

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

Nouns the Third Declension Is Generally Considered to Be A

CHAPTER 7 Third Declension : Nouns The third declension is generally considered to be a "pons asinorum" of Latin grammar. But I disagree. The third declension, aside for presenting you a new list of case endings to memorize, really involves no new grammatical principles you've haven't already been working with. I'll take you through it slowly, but most of this guide is actually going to be review. CASE ENDINGS The third declension has nouns of all three genders in it. Unlike the first and second declensions, where the majority of nouns are either feminine or masculine, the genders of the third declension are equally divided. So you really must pay attention to the gender markings in the dictionary entries for third declension nouns. The case endings for masculine and feminine nouns are identical. The case endings for neuter nouns are also of the same type as the feminine and masculine nouns, except for where neuter nouns follow their peculiar rules: (1) the nominative and the accusative forms are always the same, and (2) the nominative and accusative plural case endings are short "-a-". You may remember that the second declension neuter nouns have forms that are almost the same as the masculine nouns - except for these two rules. In other words, there is really only one pattern of endings for third declension nouns, whether the nouns are masculine, feminine, or neuter. It's just that neuter nouns have a peculiarity about them. So here are the third declension case endings. Notice that the separate column for neuter nouns is not really necessary, if you remember the rules of neuter nouns. -

Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds

Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato Ancient Greek Verb-Initial Compounds Their Diachronic Development Within the Greek Compound System Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS ISBN 978-3-11-041576-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041582-7 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041586-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Umschlagabbildung: Paul Klee: Einst dem Grau der Nacht enttaucht …, 1918, 17. Aquarell, Feder und Bleistit auf Papier auf Karton. 22,6 x 15,8 cm. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern. Typesetting: Dr. Rainer Ostermann, München Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS This book is for Arturo, who has waited so long. Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Olga Tribulato - 9783110415827 Downloaded from PubFactory at 08/03/2016 10:10:53AM via De Gruyter / TCS Preface and Acknowledgements Preface and Acknowledgements I have always been ὀψιανθής, a ‘late-bloomer’, and this book is a testament to it. -

Adjective in Old English

Adjective in Old English Adjective in Old English had five grammatical categories: three dependent grammatical categories, i.e forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified – number, gender and case; definiteness – indefiniteness and degrees of comparison. Adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instrumental. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong Declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between the declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, o-, u- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a-stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of o-stems – in the Fem. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: -um for Dat. sg, -ne for Acc. Sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. Therefore the strong declension of adjectives is sometimes called the ‘pronominal’ declension. As for the weak declension, it uses the same markers as n-stems of nouns except that in the Gen. -

Interrogative Words: an Exercise in Lexical Typology

Interrogative words: an exercise in lexical typology Michael Cysouw [email protected] Bantu grammer: description and theory 3; Session on question formation in Bantu ZAS Berlin – Friday 13 Februari 2004 1 Introduction Wer, wie, was? Der, die, das! Wieso, weshalb, warum? Wer nicht fragt, bleibt dumm! (German Sesame Street) This is first report on a study of the cross-linguistic diversity of interrogative words.1 The data are only preliminary and far from complete – for most of the languages included I am not sure whether I have really found all interrogative words (the experience with German shows that it is not do easy to collect them all). Further, the sample of languages investigated (see appendix) is not representative of the world’s languages, though it presents a fair collection of genetically and areally diverse languages. I will not say too much about relative frequencies, but mainly collect cases of particular phenomena to establish guidelines for further research. (1) Research questions a. What can be asked by an interrogative word? Which kind of interrogative categories are distinguished in the world’s languages? Do we need more categories than the seven lexicalised categories in English – who, what, which, where, when, why and how? b. Can all attested question words be expressed in all languages? For example, the German interrogative word wievielte is hardly translatable into English ‘how manieth’. c. How do the the interrogative words look like? – Have all interrogative categories own lexicalised/phrasal forms, or are they homonomous with other interrogative categories? For example, English ‘how did you do it?’ and ‘how long is it?’ use the same interrogative word, but this is not universally so. -

Subject-Verb Word-Order in Spanish Interrogatives: a Quantitative Analysis of Puerto Rican Spanish1

Near-final version (February 2011): under copyright and that the publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use or reprint the material in any form Brown, Esther L. & Javier Rivas. 2011. Subject ~ Verb word-order in Spanish interrogatives: a quantitative analysis of Puerto Rican Spanish. Spanish in Context 8.1, 23–49. Subject-verb word-order in Spanish interrogatives: A quantitative analysis of Puerto Rican Spanish1 Esther L. Brown and Javier Rivas We conduct a quantitative analysis of conversational speech from native speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish to test whether optional non-inversion of subjects in wh-questions (¿qué tú piensas?) is indicative of a movement in Spanish from flexible to rigid word order (Morales 1989; Toribio 2000). We find high rates of subject expression (51%) and a strong preference for SV word order (47%) over VS (4%) in all sentence types, inline with assertions of fixed SVO word order. The usage-based examination of 882 wh-questions shows non-inversion occurs in 14% of the cases (25% of wh- questions containing an overt subject). Variable rule analysis reveals subject, verb and question type significantly constrain interrogative word order, but we find no evidence that word order is predicted by perseveration. SV word order is highest in rhetorical and quotative questions, revealing a pathway of change through which word order is becoming fixed in this variety. Keywords: word order, language change, Caribbean Spanish, interrogative constructions 1. Introduction In typological terms, Spanish is characterized as a flexible SVO language. As has been shown by López Meirama (1997: 72), SVO is the basic word order in Spanish, with the subject preceding the verb in pragmatically unmarked independent declarative clauses with two full NPs (Mallinson & Blake 1981: 125; Siewierska 1988: 8; Comrie 1989).