How the US Twenty-Third Special Troops Fooled the Nazis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luverne Ostby.Qxd

Luverne Ostby Luverne Ostby was born on 23 July 1922 and was raised in rural Minnesota. He left for military service in September 1941. After being sworn in at Fort Snelling, he was sent to Camp Claibourne Louisiana for his basic training. Early on in his training at Camp Claibourne he was called aside and confronted by an officer that asked him if he spoke Norwegian, upon which his reply was yes. The officer asked “Why don’t you answer in Norwegian?” and pointed to a large tent instructing him to go there. Inside was a tent full of Norwegian speaking soldiers including a neighbor, Bob Stay. The group was sent to Camp Ripley Minnesota to begin training. Ostby was chosen to become a part of the 99th Battalion separate, a unit specifically made up of soldiers able to speak Norwegian. The plan was for the unit to help with the Norwegian Occupation Code Named PLOUGH. Four objectives were expected for be obtained in this mission: first to elimi- nate Norway as an economic asset for Germany, second, force Germany to keep large numbers of troops on occupation duty in Norway and away from other active fronts, third, limit the ability of German troops in Norway to attack allied convoys transporting to the Russian port of Murmansk, and fourth, prepare for the future occupation of Norway, and create a link through Norway to Russia. In December 1942, the battalion including Luverne was transferred to Camp Hale Colorado. They were expected to receive extensive winter training and Ostby was issued skis for training. -

Identificación De Criminales De Guerra· Llegados a La Argentina Según Fuentes Locales

Ciclos, Año X, Vol. X, N° 19, 1er. semestre de 2000 Documentos Identificación de criminales de guerra· llegados a la Argentina según fuentes locales Carlota Jackisch* y Daniel Mastromauro** El presente trabajo documenta él ingreso al país de criminales de guerra y responsables de crímenes contra la humanidad, pertenecientes al nazis mo y a regímenes aliados al Tercer Reich, o bajo su ocupación. Se trata de una muestra de 65 casos de un total de 180 individuos detectados, alema nes y de otras nacionalidades, tanto sospechados como encausados, pro cesados o convictos de tales crímenes. Parte de un universo que segura mente excede los 180, la información ofrecidaproviene de la consulta, por vez primera, de fuentes documentales del Ministerio. del Interior (sección documentación personal de la Policía Federal y área certificaciones de la Dirección General de Migraciones.) El relevamiento de tales fuentes se hi zo sobre la base de sus identidades reales o del conocimiento a partir de fuentes extranjeras de las identidades ficticias con que ingresaron al país. Se ofrece a contunuación una sinopsis biográfica de los criminales de gue rra nazis y colaboracionistas que llegaron a la Argentina al finalizar el con flicto bélico. Nazis ALVEN8LEBEN, Ludolf Hermann Dirigente de las SS (Schutzstajjel-Escuadras de Protección Nazis) en Rusia. Su detención fue ordenada por un juzgado de Munich, República Federal de Alema nia, acusado de la matanza de polacos según datos de la Zentraller Stelleder Lan desjustízverwaltung (en adelante Ludwigsburgo), el organismo alemán que .con- * Fundación Konrad Adenauer. ** Universidad de Buenos Aires. 218 Carlota Jackisch y Daniel Mastromauro centra toda la Información que la justicia alemana posee sobre, acusados, de haber cometido delitos relacionados con el accionar delrégimen nacionalsocialista. -

Krinkelt–Rocherath in Belgium on December 17–18, 1944 During the German Ardennes Offensive

CONTENTS Introduction Chronology Design and Development Technical Specifications The Combatants The Strategic Situation Combat Statistics and Analysis Aftermath Further Reading INTRODUCTION The rocket-propelled grenade launcher (RPG) has become a ubiquitous weapon on the modern battlefield; and all of these weapons trace their lineage back to the American 2.36in rocket launcher, better known as the bazooka. The bazooka was the serendipitous conjunction of two new technologies: the shaped-charge antitank warhead and the shoulder-fired rocket launcher. This book looks at the development of this iconic weapon, and traces its combat use on the World War II battlefield. One of the widespread myths to have emerged about German tank design during World War II was the notion that German sideskirt armor was developed in response to the bazooka, and its British equivalent, the PIAT (Projector Infantry Antitank). American and British troops began encountering the new versions of German armored vehicles with extra armor shields in 1944, and so presumed that this new feature was in response to the Allied shaped-charge weapons. The shields received a variety of names including “bazooka shields,” “bazooka pants,” and “PIAT shields.” In reality, their development was not a response to Allied shaped-charge weapons, for most German innovations in tank technology during the war years were prompted by developments on the Eastern Front. This book examines the real story behind the bazooka shields. It also traces the many specialized devices developed by the Wehrmacht in World War II to deal with the threat of infantry close-attack weapons. A remarkable variety of curious devices was developed including a wood paste to defend against antitank charges, and a machine gun with a special curved barrel to allow armored vehicle crews to defend themselves from within the protective armor of their vehicle. -

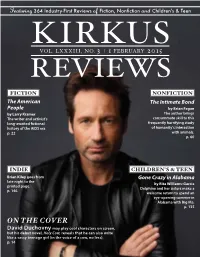

Kirkus Online 020115

Featuring 364 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfictionand Children's & Teen KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 3 | 1 FEBruARY 2015 REVIEWS FICTION NONFICTION The American The Intimate Bond People by Brian Fagan by Larry Kramer The author brings The writer and activist's consummate skill to this long-awaited fictional frequently horrifying study history of the AIDS era of humanity's interaction p. 22 with animals. p. 60 INDIE CHILDREN'S & TEEN Brian Kiley goes from Gone Crazy in Alabama late night to the by Rita Williams-Garcia printed page. Delphine and her sisters make a p. 146 welcome return to spend an eye-opening summer in Alabama with Big Ma. p. 135 on the cover David Duchovny may play cool characters on screen, but his debut novel, Holy Cow, reveals that he can also write like a sassy teenage girl (in the voice of a cow, no less). p. 14 from the editor’s desk: Chairman What to Watch for in February HERBERT SIMON BY ClaiBorne Smith # President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN Chief Operating Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN Photo courtesy Michael Thad Carter courtesy Photo Editors love to make neat lists of 10s: the 10 best books of the year, the 10 great- [email protected] est movies of all time. There are more than 10 notable books being published Editor in Chief CLAIBORNE SMITH this month (and more than the 16 I mention below), but these are the titles that [email protected] stand out to me. Included are the final lines of our reviews of these books. Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU Asali Solomon (Disgruntled, fiction, Feb. -

D-DAY in NORMANDY Speaker: Walter A. Viali, PMP Company

D-DAY IN NORMANDY Speaker: Walter A. Viali, PMP Company: PMO To Go LLC Website: www.pmotogo.com Welcome to the PMI Houston Conference & Expo and Annual Job Fair 2015 • Please put your phone on silent mode • Q&A will be taken at the close of this presentation • There will be time at the end of this presentation for you to take a few moments to complete the session survey. We value your feedback which allows us to improve this annual event. 1 D-DAY IN NORMANDY The Project Management Challenges of the “Longest Day” Walter A. Viali, PMP PMO To Go LLC WALTER A. VIALI, PMP • Worked with Texaco in Rome, Italy and in Houston, Texas for 25 years and “retired” in 1999. • Multiple PMO implementations throughout the world since 1983. • On the speaker circuit since 1987. • PMI member since 1998, became a PMP in 1999. • Co-founder of PMO To Go LLC (2002). • PMI Houston Chapter Board Member from 2002 to 2008 and its President in 2007. • PMI Clear Lake - Galveston Board Member in 2009-2010. • PMI Region 6 Mentor (2011-2014). • Co-author of “Accelerating Change with OPM” (2013). • Project Management Instructor for UH College of Technology. 3 Project Management and Leadership in History 4 More than 9,000 of our boys rest in this foreign land they helped liberate! ‹#› 5 WHAT WAS D-DAY? • In the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, American, British, and Canadian troops launched an attack by sea, landing on the beaches of Normandy on the northern coast of Nazi-occupied France. -

Bl Oo M Sb U

B L O O M S B U P U B L I S H I N G R Y L O N D O N ADULT RIGHTS GUIDE 2 0 1 4 J305 CONTENTS FICTION . 3 NON-FICTION . 17 SCIENCE AND NatURE. 29 BIOGRAPHY AND MEMOIR ���������������������������������������������������������� 35 BUSINESS . 40 ILLUSTRATED AND NOVELTY NON-FICTION . 41 COOKERY . 44 SPORT . 54 SUBAGENTS. 60 Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. 50 Bedford Square Phoebe Griffin-Beale London WC1B 3DP Rights Manager Tel : +44 (0) 207 631 5600 Asia, US [email protected] Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5876 www.bloomsbury.com [email protected] Joanna Everard Alice Grigg Rights Director Rights Manager Scandinavia France, Germany, Eastern Europe, Russia Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5872 Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5866 [email protected] [email protected] Katie Smith Thérèse Coen Senior Rights Manager Rights Executive South and Central America, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, Greece, Israel, Arabic speaking Belgium, Netherlands, Italy countries Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5873 Tel: +44 (0) 207 631 5867 [email protected] [email protected] FICTION The Bricks That Built the Houses BLOOMSBURY UK PUBLICATION DATE: Kate Tempest 01/02/2016 Award-winning poet Kate Tempest’s astonishing debut novel elevates the ordinary to the EXTENT: 256 extraordinary in this multi-generational tale set in south London RIGHTS SOLD: Young Londoners Becky, Harry and Leon are escaping the city with a suitcase Brazil: Casa de Palavra; full of stolen money. Taking us back in time, and into the heart of the capital, The Bricks That Built the Houses explores a cross-section of contemporary urban life France: Rivages; with a powerful moral and literary microscope, exposing the everyday stories that lie The Netherlands: Het behind the tired faces on the morning commute, and what happens when your best Spectrum uniboek intentions don’t always lead to the right decisions. -

National Ghost Army Annotated Bibliography 15 May 2021

Ghost Army: Deceptive Communication and the Power of Illusion Caleb Sinnwell Junior Division Individual Website Website Words: 1200 Media Time: 3:00 Process Paper Words: 500 In July, I began my National History Day project by looking for a topic concerning my greatest interest area, the military. While there were many appealing possibilities, I wanted a lesser known topic with a strong theme connection. After an extensive search, I knew I had found the perfect topic after watching an incredible film clip showing soldiers lifting and moving a realistic looking inflatable tank during World War II. They were part of the Ghost Army, a top secret U.S. Army unit that impersonated Allied troops and performed deceptions to mislead the enemy. I was immediately hooked and couldn’t wait to learn more. I began research by obtaining books and journal articles to gain a strong understanding of my topic. One specific book, The Ghost Army of World War II: How One Top-secret Unit Deceived the Enemy with Inflatable Tanks, Sound Effects, and Other Audacious Fakery, by Rick Beyer and Elizabeth Sayles, provided a comprehensive account of my topic and sparked an ongoing email exchange and personal interview with Mr. Beyer, who directed me to primary sources at the National Archives, and connected me with a 97-year-old Ghost Army veteran to interview. Also, the University of Northern Iowa librarian helped me find the few available newspaper articles from the time period on this top secret topic, and “The Official History of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops,” by Lt. -

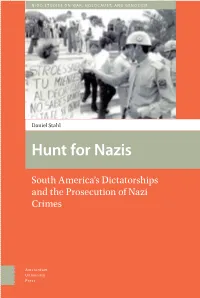

Hunt for Nazis

NIOD STUDIES ON WAR, HOLOCAUST, AND GENOCIDE Stahl Hunt for Nazis Hunt Daniel Stahl Hunt for Nazis South America’s Dictatorships and the Prosecution of Nazi Crimes Hunt for Nazis NIOD Studies on War, Holocaust, and Genocide NIOD Studies on War, Holocaust, and Genocide is an English-language series with peer-reviewed scholarly work on the impact of war, the Holocaust, and genocide on twentieth-century and contemporary societies, covering a broad range of historical approaches in a global context, and from diverse disciplinary perspectives. Series Editors Karel Berkhoff, NIOD Thijs Bouwknegt, NIOD Peter Keppy, NIOD Ingrid de Zwarte, NIOD and University of Amsterdam Advisory Board Frank Bajohr, Center for Holocaust Studies, Munich Joan Beaumont, Australian National University Bruno De Wever, Ghent University William H. Frederick, Ohio University Susan R. Grayzel, The University of Mississippi Wendy Lower, Claremont McKenna College Hunt for Nazis South America’s Dictatorships and the Prosecution of Nazi Crimes Daniel Stahl Amsterdam University Press Hunt for Nazis. South America’s Dictatorships and the Prosecution of Nazi Crimes is a translation of Daniel Stahl: Nazi-Jagd. Südamerikas Diktaturen und die Ahndung von NS-Verbrechen Original publication: © Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2013 Translation: Jefferson Chase Cover illustration: Beate Klarsfeld protesting in 1984/85 in front of the Paraguayan Court. The banner reads “Stroessner you are lying if you say that you don’t know were SS Mengele is.” Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 521 6 e-isbn 978 90 4853 624 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462985216 nur 689 © English edition: Daniel Stahl / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2018 All rights reserved. -

Hannah Arendt Und Die Frankfurter Schule

Einsicht 03 Bulletin des Fritz Bauer Instituts Hannah Arendt Fritz Bauer Institut und die Frankfurter Schule Geschichte und MMitit BeiträgenBeiträgen vonvon LLilianeiliane WWeissberg,eissberg, Wirkung des Holocaust MMonikaonika BBolloll uundnd Ann-KathrinAnn-Kathrin PollmannPollmann Editorial haben wir uns in einer Ringvorlesung den zentralen Exponenten die- ser Auseinandersetzung zugewandt: Peter Szondi, Karl Löwith, Jacob Taubes, Ernst Bloch und anderen. Unsere Gastprofessorin, Prof. Dr. Liliane Weissberg, hat in einem Seminar Hannah Arendts umstrittene These von der »Banalität des Bösen« neu beleuchtet, während das Jüdische Museum sich mit den Rückkehrern der »Frankfurter Schu- le« (Horkheimer, Adorno, Pollock u.a.) beschäftigte. Im Rahmen ei- ner internationalen Tagung führte Liliane Weissberg die beiden The- men »Hannah Arendt« und »Frankfurter Schule« zusammen. Zwei der dort gehaltenen Vorträge drucken wir in diesem Heft ab. Sie werden ergänzt durch einen Artikel zu Günther Anders, dessen Überlegungen zu »Auschwitz« und »Hiroshima« einen deutlich anderen Denkansatz in dieser deutsch-jüdischen Nachkriegsgeschichte darstellen. Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, Die vom Fritz Bauer Institut gemeinsam mit dem Jüdischen Mu- seum Frankfurt, dem Deutschen Filminstitut – DIF und CineGraph die Herbstausgabe unseres Bulletins, – Hamburgisches Centrum für Filmforschung e.V. organisierte Jah- Einsicht 02, war dem Prozess gegen John restagung der Arbeitsgruppe »Cinematographie des Holocaust« fand Demjanjuk gewidmet. Die Gerichts- dieses Jahr im Jüdischen Museum statt und hatte Benjamin Murmel- verhandlung in München hat erst nach stein (1905–1989) zum Thema. Der Rabbiner, Althistoriker, Gelehr- dem Erscheinen unseres Heftes begon- te und umstrittene letzte »Judenälteste« von Theresienstadt gewährte nen, sodass wir uns darin vor allem auf Claude Lanzmann 1975 in Rom – zur Vorbereitung seines Shoah- die Vorgänge, die zum Schwurgerichts- Films – ein 11-stündiges Interview. -

Dos Décadas Han Trascurrido Desde El Inicio De Un Acceso

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CONICET Digital Nazis Y charlatanes en Argentina. ACERCA DE Mitos E historia TERGIVersada IGNACIO KLICH (Universidad de Buenos Aires) CRISTIAN BUCHRUCKER (CONICET, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo) Dos décadas han trascurrido desde el currido ocasional y selectivamente a una inicio de un acceso más fluido a la docu- cantidad insignificante de documentos, mentación sobre los nazis acumulada en priorizando hallazgos personales de difícil distintos repositorios argentinos. Si bien consulta por terceros, salvo para quienes tardía, esta medida propicia, primero efec- se den por satisfechos con las copias facsi- tivizada no más que apenas, luego con milares ocasionalmente reproducidas por mayor amplitud, comenzó a verse imple- tales periodistas, y citando a los demás de mentada a partir de 1992. Desde entonces, manera indirecta y descontextualizada. el grueso de la producción sobre esta vasta Un caso más extremo de la misma falta es temática –básicamente la del periodismo el de quienes escriben con casi la más ab- investigativo local– ha dado pocas señales soluta prescindencia de la documentación de haberse servido del consecuente acreci- e historiografía, como si se pudiese lograr miento de la materia prima disponible. un texto de historia seria a puro artificio, La calidad de gran parte de esa produc- con asertos cuya validez está más allá del ción periodística revela, en todo caso, que aporte de evidencia firme en su apoyo. ella no ha abrevado demasiado en tan rica, Como posible justificación de tan limita- aún si incompleta, fuente. En rigor, tales do aprovechamiento de los registros dispo- escritos se produjeron mayormente con nibles, no escasean las alusiones a «miles y prescindencia de casi todo el material de miles de documentos» más, «guardados en archivos argentinos y extranjeros, como si inasibles archivos que nadie tiene interés estos papeles no existiesen o el acceso a en mostrar y que son difíciles de hallar»1. -

Deutsche Kommandounternehmen Während Der Ardennenoffensive

Deutsche Kommandounternehmen während der Ardennenoffensive Autor(en): Sievert, Kaj-Gunnar Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: ASMZ : Sicherheit Schweiz : Allgemeine schweizerische Militärzeitschrift Band (Jahr): 180 (2014) Heft 6 PDF erstellt am: 25.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-391460 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Geschichte Deutsche Kommandounternehmen während der Ardennenoffensive Ende 1944 stehen die Westalliierten an der Grenze zu Deutschland. Mit dem Unternehmen «Wacht am Rhein» – auch « Ardennenoffensive » genannt – will die deutsche Wehrmacht dem Gegner eine Niederlage zufügen und gleichzeitig den Hafen von Antwerpen zurückerobern. Spezialkommandos und Fallschirmjäger sollen die Offensive unterstützen. Eine Analyse des Einsatzes. -

Canadian Military Journal, Issue 14, No 1

Vol. 14, No. 1, Winter 2013 CONTENTS 3 EDITOR’S CORNER 6 LETTER TO THE EDITOR FUTURE OPERATIONS 7 WHAT IS AN ARMED NON-STATE Actor (ANSA)? by James W. Moore Cover AFGHANISTAN RETROSPECTIVE The First of the Ten Thousand John Rutherford and the Bomber 19 “WAS IT worth IT?” CANADIAN INTERVENTION IN AFGHANISTAN Command Museum of Canada AND Perceptions OF SUccess AND FAILURE by Sean Maloney CANADA-UNITED STATES RELATIONS 32 SECURITY THREAts AT THE CANADa-UNITED STATES BORDER: A QUEST FOR IMPOSSIBLE PERFECTION by François Gaudreault LESSONS FROM THE PAST 41 PRESIDENT DWIGHT D. Eisenhower’S FArewell ADDRESS to THE NATION, 17 JANUARY 1961 ~ AN ANALYSIS OF COMpetinG TRUTH CLAIMS AND its RELEVANCE TODAY by Garrett Lawless and A.G. Dizboni 47 BREAKING THE STALEMATE: AMphibioUS WARFARE DURING THE FUTURE OPERATIONS WAR OF 1812 by Jean-Francois Lebeau VIEWS AND OPINIONS 55 NothinG New UNDER THE SUN TZU: TIMELESS PRINCIPLES OF THE OperATIONAL Art OF WAR by Jacques P. Olivier 60 A CANADIAN REMEMBRANCE TRAIL FOR THE CENTENNIAL OF THE GREAT WAR? by Pascal Marcotte COMMENTARY 64 DEFENCE ProcUREMENT by Martin Shadwick 68 BOOK REVIEWS AFGHANISTAN RETROSPECTIVE Canadian Military Journal / Revue militaire canadienne is the official professional journal of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence. It is published quarterly under authority of the Minister of National Defence. Opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of National Defence, the Canadian Forces, Canadian Military Journal, or any agency of the Government of Canada.