In Four Works of Pedro Juan Gutiérrez

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Versos Satánicos

LOS VERSOS SATÁNICOS SALMAN RUSHDIE Salman Rushdie - Los versos satánicos http://elortiba.galeon.com ÍNDICE I EL ÁNGEL GIBREEL ............................................................................................................................................. 6 II MAHOUND............................................................................................................................................................54 III ELEOENE DEERREEESE ..................................................................................................................................... 75 IV AYESHA ............................................................................................................................................................... 117 V UNA CIUDAD VISIBLE PERO NO VISTA ................................................................................................................................................. 137 VI REGRESO A JAHILIA ........................................................................................................................................ 201 VII EL ÁNGEL AZRAEEL ........................................................................................................................................ 221 VIII LA RETIRADA DEL MAR DE ARABIA ...................................................................................................................................... 263 IX UNA LÁMPARA MARAVILLOSA .................................................................................................................. -

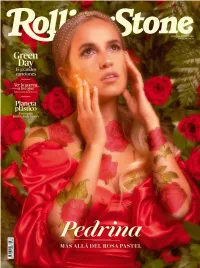

RS057 PEDRINA WEB.Pdf

ILUSTRACIÓN POR Ataul ROLLING STONE COLOMBIA Online EDITOR & PUBLISHER: Diego Ortiz EDITORA EJECUTIVA: Bibiana Quintana Pinilla HIP-HOP DIRECTOR DE CONTENIDOS: Ricardo Durán COORDINADOR DIGITAL: Santiago Andrade SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER: Sonia Barrera ASISTENTE PRACTICANTE El vuelo de SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER: Martín Toro COORDINADORA EDITORIAL: Francesca Quintero Bello Sr. Pablo y EDITOR SENIOR: Rodrigo Torrijos REDACTOR SENIOR: David Valdés VIDEO MEDIA PRODUCER: Rodrigo Torrijos Thomas Parr DIRECCIÓN DE ARTE Y FOTOGRAFÍA: Diego Ortiz Después de lanzar el EP Levitar, EDITORA GRÁFICA: Cindy Johanna Morales Cristancho ASISTENTE GRÁFICA: María Camila Morales Cristancho los MCs paisas preparan un álbum COLABORADORES: David Browne, Tim Dickinson, Jon de larga duración con ritmos más Dolan, Patrick Doyle, Angie Martoccio, Camilo Romero, traperos y experimentales. Amy X. Wang. TASTY MEDIA CHAIRMAN: Diego Ortiz VICEPRESIDENTE: Bibiana Quintana PRODUCCIÓN EJECUTIVA: Bibiana Quintana, Diego Ortiz, Juan Pablo Añez DIRECTOR COMERCIAL: Carlos Mario Quintana DIRECTOR FINANCIERO: Alejandro Ortiz EJECUTIVA COMERCIAL: María Camila Rozo ROLLING STONE USA PRESIDENT & CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER: Gus Wenner MANAGING EDITOR: Jason Fine DEPUTY MANAGING EDITOR: Sean Woods ASSISTANT EDITORS: Suzy Exposito SENIOR WRITERS: David Browne, David Fricke, Andy Greene, Kory Grow, Brian Hiatt, Stephen Rodrick, Jamil Smith, Matt Taibbi, Peter Travers SENIOR EDITORS: Patrick Doyle, Rob Fischer, Thomas Walsh CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Joe Hutchinson DIRECTOR OF CREATIVE CONTENT: Catriona Ni -

Generación 2018 Serafín Álvarez José Díaz Antonio Gagliano Marco Godoy Irene Grau Antoni Hervàs Lola Lasurt Elena Lavellé

Generación 2018 Serafín Álvarez José Díaz Antonio Gagliano Marco Godoy Irene Grau Antoni Hervàs Lola Lasurt Elena Lavellés Fran Meana Levi Orta Proyectos de arte de la Fundación Montemadrid 3 El certamen Generaciones es en nuestro país uno de los proyectos de referencia en el apoyo a la creación contemporánea, que viene siendo premiada y exhibida desde el año 2000 en el marco de esta iniciativa. La Fundación Montemadrid, en su labor de impulsar una vez más esta convocatoria, presenta en La Casa Encendida la exposición Generación 2018, formada por obras producidas para la ocasión por los diez jóvenes artistas que han sido seleccionados por un jurado de reconocido prestigio y cuyos proyectos han recibido cada uno idéntica dotación económica. Como en ediciones anteriores, las prácticas y conceptos con los que trabajan los artistas elegidos son tan heterogéneos como rica y variada es nuestra escena artística. Sin embargo, se pueden señalar afinidades, no solo en la manera de formalizar los proyectos a través de instalaciones con la incorporación de vídeos, fotografías, objetos o dibujos, sino también en ciertas inquietudes compartidas que están en esta ocasión relacionadas con visiones oscuras del presente o el futuro, y que se abordan ya sea rescatando del archivo del olvido aquello que no pudo ser, presentando como espacios de libertad zonas prohibidas, escondidas, o bien, en una crítica al estado de bienestar actual, señalando los códigos de la autoridad e investigando «lo negro» de los elementos que subyacen al capitalismo vigente. Quisiera -

Spanglish Code-Switching in Latin Pop Music: Functions of English and Audience Reception

Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 II Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 © Magdalena Jade Monteagudo 2020 Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception Magdalena Jade Monteagudo http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract The concept of code-switching (the use of two languages in the same unit of discourse) has been studied in the context of music for a variety of language pairings. The majority of these studies have focused on the interaction between a local language and a non-local language. In this project, I propose an analysis of the mixture of two world languages (Spanish and English), which can be categorised as both local and non-local. I do this through the analysis of the enormously successful reggaeton genre, which is characterised by its use of Spanglish. I used two data types to inform my research: a corpus of code-switching instances in top 20 reggaeton songs, and a questionnaire on attitudes towards Spanglish in general and in music. I collected 200 answers to the questionnaire – half from American English-speakers, and the other half from Spanish-speaking Hispanics of various nationalities. -

Gustavo Cerati, Goodbye to a Legend

Gustavo Cerati Dies: Soda Stereo Front Man Dead At 55 From Respiratory Arrest After 4 Years In Coma Entertainment Fashion+Beauty Entertainment VIDEO: Eiza Gonzalez Denise Bidot Launches En Is Kate Del Castillo Refuses To Talk About 'No Wrong Way' 5 Be Meeting 'El Chapo' In Giovani Dos Santos Movement With 'La P NY Jail? Romance Unretouched Photos Entertainment ADVERTISEMENT Gustavo Cerati Dies: Soda Stereo Front Man Dead At 55 From Respiratory Arrest After 4 Years In Coma Like Twitter Comment Email By Maria G. Valdez | Sep 04 2014, 01:10PM EDT Most Read 1. Lifestyle 5 Ways To Rum Right All Year Long 2. Entertainment VIDEO: Eiza Gonzalez Refuses To Talk About Giovani Dos Santos Romance 3. Lifestyle 11 Beauty Essentials To Celebrate Spring 4. Entertainment Is Natasha Dupeyrón A Lesbian? Televisa Actress Breaks Silence On Gay Rumors 5. Entertainment Netflix April 2017 Full List New Releases: Gustavo Cerati has died, according to his doctor. The Argentine musician and front man of Soda Stereo died from See What Movies, TV Series Are Coming respiratory arrest following 4 years in a coma. Reuters ADVERTISEMENT Today is a sad day for music. Gustavo Cerati has died. He was 55. In an official notice on his website and social media accounts, the following message was published: “We communicate that the patient Gustavo Cerati died in the early hours of the morning, as a consequence of a respiratory arrest.” His doctor, Gustavo Barbalace, the Medical Director from the ALCLA Clinic in Buenos Aires, Argentina, signed the message. Meanwhile, his family asked for respect and consideration during these difficult times. -

CORRIDO NORTEÑO Y METAL PUNK. ¿Patrimonio Musical Urbano? Su Permanencia En Tijuana Y Sus Transformaciones Durante La Guerra Contra Las Drogas: 2006-2016

CORRIDO NORTEÑO Y METAL PUNK. ¿Patrimonio musical urbano? Su permanencia en Tijuana y sus transformaciones durante la guerra contra las drogas: 2006-2016. Tesis presentada por Pedro Gilberto Pacheco López. Para obtener el grado de MAESTRO EN ESTUDIOS CULTURALES Tijuana, B. C., México 2016 CONSTANCIA DE APROBACIÓN Director de Tesis: Dr. Miguel Olmos Aguilera. Aprobada por el Jurado Examinador: 1. 2. 3. Obviamente a Gilberto y a Roselia: Mi agradecimiento eterno y mayor cariño. A Tania: Porque tú sacrificio lo llevo en mi corazón. Agradecimientos: Al apoyo económico recibido por CONACYT y a El Colef por la preparación recibida. A Adán y Janet por su amistad y por al apoyo desde el inicio y hasta este último momento que cortaron la luz de mi casa. Los vamos a extrañar. A los músicos que me regalaron su tiempo, que me abrieron sus hogares, y confiaron sus recuerdos: Fernando, Rosy, Ángel, Ramón, Beto, Gerardo, Alejandro, Jorge, Alejandro, Taco y Eduardo. Eta tesis no existiría sin ustedes, los recordaré con gran afecto. Resumen. La presente tesis de investigación se inserta dentro de los debates contemporáneos sobre cultura urbana en la frontera norte de México y se resume en tres grandes premisas: la primera es que el corrido y el metal forman parte de dos estructuras musicales de larga duración y cambio lento cuya permanencia es una forma de patrimonio cultural. Para desarrollar esta premisa se elabora una reconstrucción historiográfica desde la irrupción de los géneros musicales en el siglo XIX, pasando a la apropiación por compositores tijuanenses a mediados del siglo XX, hasta llegar al testimonio de primera mano de los músicos contemporáneos. -

La Ciudad Rinde Homenaje a Gustavo Cerati

Publicado en Buenos Aires Ciudad - Gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires ( https://www.buenosaires.gob.ar) Buenos Aires > La Ciudad rinde homenaje a Gustavo Cerati La Ciudad rinde homenaje a Gustavo Cerati [1] Gustavo Cerati desarrolló gran parte de su carrera en Buenos Aires; junto a Soda Stereo o como solista fue impulsor en la Ciudad de acontecimientos musicales únicos que convocaron a cientos de miles de personas y a distintas generaciones de fans de la Argentina y del mundo. Nació el 11 de agosto de 1959, en Barracas; fue durante sus estudios en la Universidad de El Salvador, en 1979, que conoció a Héctor ?Zeta Bosio? con quien junto a Charly Alberti formaría a comienzos de los ochentas el legendario Soda Stereo. Foto: Facebook Gustavo Adrián Cerati Sus primeras presentaciones en 1983 fueron en la discoteca porteña Airport y en el Stud Free Pub, este último ubicado en Av. Del Libertador 5665. En 1988, para Doble Vida, el cuarto disco de estudio de Soda, Cerati compuso una de sus canciones más recordadas y que tienen a Buenos Aires como protagonista: La Ciudad de la furia. En una época en la que los videoclips eran clave para la difusión, el de la canción incluyó imágenes de las cúpulas de la Diagonal Norte, la calle Florida, entre otros paisajes porteños. Ya hacía tiempo que Soda Stereo y la poesía de Cerati se habían ganado el corazón de sus fans en la Argentina y Latinoamérica. Foto: Facebook Gustavo Adrián Cerati Hay algunos recitales de su trayectoria con el grupo o en calidad de solista realizados en la Ciudad que han quedado grabados en el imaginario colectivo. -

Todos Son Vagabundas

Aquí todos son Vagabundas Pedro Peña Autor: Pedro Peña Titulo: Aquí todos son vagabundas Deposito legal: If50320148002247 ISBN: 978-980-7668-93-4 Serie: Rodolfo Santana Impreso en Venezuela por: Fundación Negro sobre Blanco Grupo Editorial Derechos Reservados – Es propiedad del autor Prefacio Sean bienvenidos al Teatro. Por poco no logran entrar, pues iniciada la función se cierran las puertas de madera inmortal para así acaparar la mayor placidez, que necesitan, no sólo los actores, sino ustedes: el público; bendito público que será testigo de una bella función, donde con gran deseo seles querrá satisfacer. No hay mayor satisfacción que haber dejado en los espectadores una máxima emoción; emoción que puede abarcar un sinfín de trasfiguraciones. ¿Qué donde se encuentra dicho teatro? Pues aquí y en todas partes; la vida en si es un teatro y una función; por tanto: hay que saber actuar la vida, diría por allí algún gran sabio. Como ya he dicho, dicho teatro se encuentra en todas partes, pero que te baste con saber que en este momento el teatro lo tienes frente a ti. Dirección exacta: calle Presente, entre carrera Pasado y carrera Futuro; junto a la casa Filosofía. Pero no perdamos más tiempo que la función está por comenzar. Por favor, sigan adelante; sigan adelante y déjense cautivar. Eso sí: guardar silencio y prestar atención: es la imaginación la que nos hará vivir. Pedro Peña Esta obra está enmarcada dentro del Teatro del Trasfigurismo. Un teatro que mantiene en expectativa al público por lo que podrá ver o no; un teatro que va directo a la crítica, sin importar a qué apunte. -

Los Disfraces De La Disidencia En La Música Cubana Alternativa

Université de Montréal Los disfraces de la disidencia en la música cubana alternativa trova, rap, punk par Nicola Giovagnoli Département de littératures et de langues modernes Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.A. en études hispaniques Hiver 2015 © Nicola Giovagnoli, avril 2015 Université de Montréal Faculté des études supérieures et postdoctorales Ce mémoire intitulé: Los disfraces de la disidencia en la música cubana alternativa trova, rap, punk présenté par Nicola Giovagnoli a été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Javier Rubiera, président-rapporteur Ana Belén Martín Sevillano, directeur de recherche James Cisneros, membre du jury RÉSUMÉ ET MOTS-CLÉS Ma recherche vise à comprendre de quelle façon les principales questions économiques (carences alimentaires et énergétiques), sociales (émigration massive, inégalités, racisme), politiques (manque de liberté, autoritarisme) et culturelles (immobilisme, censure) qui se produisent à Cuba depuis 1990 jusqu’à nos jours, se reflètent sur l’œuvre artistique d'un certain nombre de groupes musicaux. L’objectif de cette étude est de définir si ces expressions artistiques peuvent être considérées comme un miroir de la société de cette période, puisque elles contemplent des aspects d’intérêt public que le discours officiel tait. L’analyse veut examiner les stratégies discursives des paroles d’une certaine production musicale représentative d’un champ musical riche et complexe. D’autre part, l’étude vise à comprendre si la musique peut être considérée comme un espace de société civile dans un contexte qui empêche la libre formation d’agents sociaux. -

Publicación: Castro, Ernesto (2019). El Trap. Filosofía Millennial Para La Crisis En España

Publicación: Castro, Ernesto (2019). El trap. Filosofía millennial para la crisis en España. Madrid: Errata Naturae Fragmento: Ser o no ser feminista / El retorno de lo real (pp. 165-218) y (pp. 358-380) ISBN: 978-84-17800-11-6 6. SER O NO SER FEMINISTA Me suda la polla lo que tú me digas. 1 No me hables, me das SIDA. 1 Vece a la mierda y que Dios te bendiga. 1 Esto es trap shit, pero no soy trapera, 1 lo juro por tos mis muertos, que Dios no los quiera. 1 Estoy pensando en billetes, en llenar la nevera. 1 [... ) Estoy ha blando con Dios, pero nadie se entera. 1 Mi futuro está envuelto en el papel de mi cartera. ALBA NY t,. J. Sad and emo girls lln diciembre de 2017, Pimp Flaco hizo unas desafortunadas declaraciones en Los 40 Principales sobre las mujeres de la es n:na urbana española. Cuando el presentador de esa emisora de radio le preguntó su opinión acerca de Bad Gyal, el trapero de lbdalona respondió lo siguiente: «Bueno, a ver, es como cuando t• n tu clase hay dos niñas que están buenas, pues ... pues son esas dos. Aquí, en España, está una y la otra. Pues, si no petan esas dos, no peta nadie, hermano. Pues, cuando salgan quince ni iias más dentro de tres o cuatro años, adiós. Así es la vida, 165 1 ht•r·mono>>• Lo más desafortunado de esas declaracion~:s de ser problemática, ya que, por mucho que las mujeres digan acreedoras del mayor de los facepalms- no fue la comparn que ellas no se hipersexualizan para los hombres, sino para sí ción con las niñas que están buenas en el colegio, como sugi rnismas, al patriarcado le dan igual tus intenciones: el caso es riendo micromachistamente que las traperas españolas son que la mayoría de las artistas urbanas ofrece en sus vídeos justo unas ingenuas e infantiles colegialas que han tenido éxito den lo que los babosos y los pajilleros compulsivos demandan de tro de la industria del espectáculo gracias a su físico antes que a l• llas (mujeres ligeras de ropa moviendo las tetas y el culo). -

Perspectiva De Envejecimiento Y Vejez En Personas Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales, Transgénero E Intersexuales

Perspectiva de Envejecimiento y Vejez en Personas Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales, Transgénero e Intersexuales ALCALDÍA MAYOR DE BOGOTÁ D.C. Secretaría PLANEACIÓN Tanto silencio puede significar que a nadie le importa -Perspectiva de Envejecimiento y Vejez en Personas Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales, Transgénero e Intersexuales- 1 Marlon Ricardo Acuña Rivera Bogotá, 2019 1 Este documento fue elaborado en el marco del contrato de prestación de servicios No. 203 de 2019 que tenía por objeto “Prestar servicios profesionales a la Dirección de Diversidad Sexual para apoyar la recolección y compilación de historias de vida de adultos mayores de los sectores sociales LGBTI” 2 Perspectiva de Envejecimiento y Vejez en Personas Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales, Transgénero e Intersexuales ALCALDÍA MAYOR DE BOGOTÁ SECRETARÍA DISTRITAL DE PLANEACIÓN Secretario Distrital de Planeación Andrés Ortiz Gómez Subsecretaria de Planeación Socioeconómica Paola Gómez Campos Director de Diversidad Sexual Juan Carlos Prieto García 3 Perspectiva de Envejecimiento y Vejez en Personas Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales, Transgénero e Intersexuales A todas las personas mayores LGBTI y organizaciones sociales que trabajan a favor de los derechos de las personas mayores: gracias por su participación, su tiempo, sus enseñanzas y su empeño para dejar de ser invisibles. 4 Perspectiva de Envejecimiento y Vejez en Personas Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales, Transgénero e Intersexuales INTRODUCCIÓN El presente documento es el resultado de un proceso de concertación desarrollado desde la Dirección de Diversidad Sexual, de la Secretaria Distrital de Planeación, con personas mayores y organizaciones sociales LGBTI, con las cuales se identificó la necesidad de indagar, visibilizar y formular acciones conjuntas que permitan implementar una perspectiva integral de envejecimiento y vejez en los programas institucionales, así como en la agenda social de los organizaciones y liderazgos LGBTI. -

Yandel Update Album Download Zipp Yandel Update Album Download Zipp

yandel update album download zipp Yandel update album download zipp. Artist: Yandel Album: The One Released: 2019 Style: Reggae. Format: MP3 320Kbps. Tracklist: 01 – Calent¢n 02 – Sumba Yandel 03 – Perreito Lite 04 – Dime 05 – Que No Acabe 06 – Coraje 07 – Sola Solita 08 – Calcuradora 09 – Tequila 10 – Una Se¤al 11 – Pom Pom 12 – M¡a M¡a 13 – Una Vez M s 14 – Te Amar‚ 15 – No S‚ 16 – No Se Olvida 17 – Pa Que Goce. DOWNLOAD LINKS: RAPIDGATOR: DOWNLOAD TURBOBIT: DOWNLOAD. #Update. The wily urban master Yandel announced his membership in the new generation Latin trap movement with the video and single "Explícale" featuring Bad Bunny. That track appears at the close of this 14-cut master class in tough, reggae- saturated Latin grooves. More than this, #Update is a testament to collaboration -- only five of its tracks are solo. The rest include an all-star guest list that features old and new friends including Wisin, Zion & Lennox, Maluma, J. Balvin, Ozuna, Becky G., and Luis Fonzi. Among the highlights, are his smash "Mi Religion," the dubby solo track "No Pare," and the futuristic "Si Se Da" with Plan B. 360Media Music. Latest Music Update, Download Mp3 Audio songs, Music Videos, Mp4 Download, Gospel Jams, Entertainment and Celebrity News. ALBUM: Joyner Lucas – Evolution. Posted on October 23, 2020 by 360media in Albums, Music // 0 Comments. DOWNLOAD MP3 HERE. Download Joyner Lucas – Evolution Album Zip Format. Joyner Lucas returns with a new album “Evolution” and we got it for you, download fast and feel the vibes. DOWNLOAD MP3! Do you Love songs like this one? Then bookmark our page, we will update you with more highly ranked latest music Lyrics audio mp3 and Video mp4 for quick free download.