A History of the Birds of Europe, Not Observed in the British Isles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tafila Region Wind Power Projects Cumulative Effects Assessment © International Finance Corporation 2017

Tafila Region Wind Power Projects Cumulative Effects Assessment © International Finance Corporation 2017. All rights reserved. 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433 Internet: www.ifc.org The material in this work is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. IFC encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly, and when the reproduction is for educational and non-commercial purposes, without a fee, subject to such attributions and notices as we may reasonably require. IFC does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the content included in this work, or for the conclusions or judgments described herein, and accepts no responsibility or liability for any omissions or errors (including, without limitation, typographical errors and technical errors) in the content whatsoever or for reliance thereon. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The contents of this work are intended for general informational purposes only and are not intended to constitute legal, securities, or investment advice, an opinion regarding the appropriateness of any investment, or a solicitation of any type. IFC or its affiliates may have an investment in, provide other advice or services to, or otherwise have a financial interest in, certain of the companies and parties (including named herein. -

(Agosto 2019) Cambio En El Nombre Científico

Cambio en el nombre científico (agosto 2019) Cambio en el nombre científico (agosto 2018) Cambio en el nombre científico (junio 2017) Cambio en el nombre científico (octubre 2016) Cambio en el nombre científico (septiembre 2012) Cambio en el nombre científico (marzo 2011) Fuente: Gill, F and D Donsker (Eds). 2019. IOC World Bird List (v 9.2). Doi 10.14344/IOC.ML.9.2. http://www.worldbirdnames. -

Rare Birds in Nepal

ISSN: 2705-4403 (Print) & 2705-4411 (Online) www.cdztu.edu.np/njz Vol. 4 | Issue 2| December 2020 Checklist https://doi.org/10.3126/njz.v4i2.33894 Rare birds in Nepal Carol Inskipp1* | Hem Sagar Baral2,3 | Sanjib Acharya4 | Hathan Chaudhary5 | Manshanta Ghimire6 | Dinesh Giri7 13 High Street, Stanhope, Bishop Auckland, Co. Durham DL132UP, UK 2Zoological Society of London Nepal Office, PO Box 5867, Kathmandu Nepal 3School of Environmental Sciences, Charles Sturt University, Albury-Wodonga, Australia 4Koshi Bird Society, Prakashpur, Barahachhetra Municipality, Sunsari, Nepal 5Nepalese Ornithological Union, PO Box 10918, Kathmandu, Nepal 6Pokhara Bird Society, PO Box 163, Pokhara, Nepal 7Bird Education Society, Chitwan, Nepal * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 06 December 2020 | Revised: 16 December 2020 | Accepted: 16 December 2020 Abstract This paper aimed to fulfil the knowledge gap on the status of vagrants and rare birds of Nepal. Records of all Nepal’s bird species that were previously considered vagrants by the National Red List of Nepal’s Birds (2016) were collated and detailed with localities, dates and observers. Species recorded since 2016, including vagrant species, were also covered. A total of 92 species was assessed to determine if they were vagrants, that is species that had a total of 10 or less records. It was concluded that six species are no longer vagrant and we recommend these for national red list assessment. Nepal currently has a total of 71 vagrant species. In addition, four vagrant species have still to be accepted by the Nepal Rare Birds Committee before they can be officially included on the Nepal bird list. -

Abu Dhabi, September 2011 Vol 35 (7)

Abu Dhabi, September 2011 Vol 35 (7) Emirates Natural History Group Patron: H.E. Sheikh Nahayan bin Mubarak Al Nahayan ENHG focus September 2011 Page 2 EDITORIAL In this issue Welcome to a flying start after the summer break & Eid Page 1: Front cover holiday, with two lectures, two day trips and a social event on offer in Sept. And welcome to the Sept issue of Page 2: Editorial focus! Our lead article on the 2010 NH Awards highlights Page 3: Scientific Research ‗Essential‘, Says the importance our Patron, H. E. Sheikh Nahyan, places Nahyan on the research and conservation work that our Group promotes. Following that, we report on three new Page 4: ENHG Lifetime Membership Awards, Lifetime Memberships in the ENHG, awarded in June Whale Shark Tagging Update 2011. Our sincerest thanks go out to these members for Page 5: Answers to Natural Quiz #1: What Are the their vital contributions to our Group. Also included are a Differences? set of answers to the first of a planned series of natural history quizzes, introduced in May 2011. We hope it fully Page 6: Errata, Upcoming Speaker, Local News answers your questions, but if not, let us know. Media, Marine Life Rescue Contact Info. In Committee news, Dr Drew Gardner has now stepped Page 7: Corporate Sponsors, ENHG Bookstall down from the ENHG (Abu Dhabi) Chairmanship. We Page 8: Committee Members, Lectures, Field warmly thank him for his confident stewardship of our Trips, Websites of General Interest, Group over the past six and a half years. And we look Equipment for Members‘ Use, Research & forward to his imminent completion of the book he is Conservation Fund, Newsletter Details writing on the reptiles and amphibians of SE Arabia. -

Israel: Birds, History & Culture in the Holy Land November 3–15, 2021 ©2020

ISRAEL: BIRDS, HISTORY & CULTURE IN THE HOLY LAND NOVEMBER 3–15, 2021 ©2020 Eurasian Cranes, Hula Valley, Israel © Jonathan Meyrav Perched on the far edge of the Mediterranean Sea, Israel exists as a modern and safe travel destination brimming with history, culture, and nature. Positioned at the interface of three continents—Europe, Asia, and Africa—Israel sits at a geographic crossroads that has attracted both people and birds since time immemorial. From the age of the Old Testament to the present, the history of this ancient land, this Holy Land, is inscribed in the sands that blow across its fabled deserts. We are thrilled to present our multi-dimensional tour to Israel: a Birds, History & Culture trip that visits many of the country’s most important birding areas, geographical locations, and historical attractions. Our trip is timed for the end of fall migration and the onset of the winter season. Superb birding is virtually guaranteed, and we anticipate encounters with a wonderful variety of birds including year-round residents, passage migrants, and an array of African, Asian, and Mediterranean species at the edges of their range. Israel, Page 2 From the capital city of Tel Aviv, we’ll travel north along the coast to Ma’agan Michael and the Hula Valley to witness the spectacular seasonal gathering of 40,000 Common Cranes and hundreds of birds of prey including eagles, buzzards, harriers, falcons, and kites, in addition to a variety of other birds. We’ll then head to the Golan Heights, to Mount Hermon and the canyon at Gamla, home to Eurasian Griffon, Bonelli’s Eagle, Syrian Woodpecker, Blue Rock- Thrush, and Hawfinch. -

AERC TAC's TAXONOMIC RECOMMENDATIONS July 2010

AERC TAC’s TAXONOMIC RECOMMENDATIONS July 2010 Citation: Crochet P.-A., Raty L., De Smet G., Anderson B., Barthel P.H., Collinson J.M., Dubois P.J., Helbig A.J., Jiguet F., Jirle E., Knox A.G., Le Maréchal P., Parkin D.T., Pons, J.-M., Roselaar C.S., Svensson L., van Loon A.J., Yésou P. (2010) AERC TAC's Taxonomic Recommendations. July 2010. Available online at www.aerc.eu. Authorship: The three chairmen of the TAC over the past several years are listed first as they were largely responsible for the compilation of the report. Unless they did not accept it, members of the national taxonomic committees who were responsible for the decisions that fed into the report are then listed in alphabetic order, in recognition of their essential input to this document. This should not be interpreted as suggesting that they support every individual conclusion contained here. Introduction This document constitutes the official 2010 AERC TAC recommendations for species-level systematics of Western Palearctic birds. For full information on the TAC and its history, please refer to the documents on the AERC web page www.aerc.eu, including the minutes of the AERC meetings (http://www.aerc.eu/Minutes.htm) and the TAC pages (http://www.aerc.eu/aerc_tac.htm). The TAC has five members: Taxonomy Sub-committee of the British Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee (BOURC-TSC, UK), Commission de l’Avifaune Française (CAF, France), Swedish Taxonomic Committee (STC, Sweden), Commissie Systematiek Nederlandse Avifauna (CSNA, Netherlands) and German Taxonomic Committee (German TC, Germany). As decided long ago (see introduction to AERC TAC 2003), systematic changes are based on decisions published by, or directly passed to the TAC chairman, by these taxonomic committees (TCs). -

Spatio-Temporal Variation Patterns of Bird Community in the Oasis Ecosystem of the North of Algerian Sahara

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 2 Spatio-Temporal Variation Patterns of Bird Community in the Oasis Ecosystem of the North of Algerian Sahara Lasad Chiheb Department of Natural and Life Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, M’Sila University, M’Sila, Algeria., [email protected] Bensaci Ettayib Biology, Water and Environment Laboratory (LBEE), University Mai Guelma, Guelma, Algeria, [email protected] Nouidjem Yassine Department of Natural and Life Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, M’Sila University, M’Sila, Algeria, [email protected] Hadjab Ramzi Life and Nature Sciences Department, University of “Larbi Ben M'hidi”, OumEl Bouaghi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Ornithology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Chiheb, L., Ettayib, B., Yassine, N., & Ramzi, H. (2021). Spatio-Temporal Variation Patterns of Bird Community in the Oasis Ecosystem of the North of Algerian Sahara, Journal of Bioresource Management, 8 (1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.35691/JBM.1202.0161 ISSN: 2309-3854 online (Received: Nov 4, 2020; Accepted: Dec 16, 2020; Published: Jan 27, 2021) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spatio-Temporal Variation Patterns of Bird Community in the Oasis Ecosystem of the North of Algerian Sahara © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. -

Wadi Wurayah National Park, Scientific Research Report

Wadi Wurayah National Park Scientific Research Report 2013 – 2015 PROJECT PARTNERS Emirates Wildlife Society-WWF Emirates Wildlife Society-WWF is a UAE environmental nongovernmental organisation established under the patronage of H. H. Sheikh Hamdan bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the ruler’s representative in the Western Region and the chairman of Environmental Agency Abu Dhabi. Since its establishment, Emirates Wildlife Society has been working in association with WWF, one of the largest and most respected independent global conservation organisations, to initiate and implement environmental conservation and education projects in the region. EWS-WWF has been active in the UAE since 2001, and its mission is to work with people and institutions within the UAE and the region to conserve biodiversity and tackle climate change through education, awareness, policy, and science-based conservation initiatives. Fujairah Municipality Fujairah Municipality is EWS-WWFs strategic partner and the driver of the development of Wadi Wurayah National Park. The mission of Fujairah Municipality is to provide the people of Fujairah with advanced infrastructure, a sustainable environment, and excellence in services. Lead Author: HSBC Bank Middle East Ltd Jacky Judas, PhD, Research Manager, WWNP - EWS-WWF HSBC Bank Middle East is one of the largest international banks in the Middle Reviewer: East, and, since 2006, it has been the main stakeholder and financial partner of Olivier Combreau, PhD, consultant EWS-WWF on the Wadi Wurayah National Park project. HSBC Bank Middle East has funded most of the research programmes conducted to date in Wadi Wurayah National Park. EWS-WWF Head Office P.O. Box 45553 Abu Dhabi United Arab Emirates T: +971 2 634 7117 F: +971 2 634 1220 Earthwatch Institute EWS-WWF Dubai Office Earthwatch Institute is a leading global nongovernmental organisation that P.O. -

Iran Tour Report

Pleske’s Ground Jay, a most unusual corvid, is endemic to the interior deserts of Iran (Mark Beaman) IRAN 30 APRIL – 13 MAY 2017 TOUR REPORT LEADERS: MARK BEAMAN and ALI ALIESLAM It was great to get back to Iran again. What a brilliant country this is for birding, and so varied and scenic as well, never mind the hospitality of the Iranians, a much misunderstood people (so many of us conflate Iranians with their government of course). This was definitely our most successful Iran tour ever in terms of the number of specialities recorded, among a grand total of 251 bird species (as per current IOC taxonomy) and 13 species of mammal. Among the greatest highlights were the endemic Pleske’s Ground Jay, the near-endemic Caspian Tit and the restricted-range Sind Woodpecker, Mesopotamian Crow, Grey Hypocolius, Black-headed Penduline Tit, Basra Reed Warbler, Hume’s Whitethroat, Hume’s Wheatear, Red-tailed Wheatear, Iraq Babbler and Afghan Babbler, as well as Caspian Snowcock, See-see Partridge, Macqueen’s Bustard, White-cheeked Tern, Pallid Scops Owl, Egyptian Nightjar, Steppe Grey Shrike, Plain Leaf Warbler, Radde’s Accentor, Dead Sea Sparrow, Pale Rockfinch, Asian Crimson-winged Finch and Grey-necked Bunting, not to mention Indo- 1 Birdquest Tour Report: Iran 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com Sind Woodpecker is only found in Persian Baluchistan and Pakistan (Mark Beaman) Pacific Hump-backed Dolphin, Persian Ibex, Goitred Gazelle and Onager (Asiatic WildAss). The tour started with a flight from Tehran southeastwards to the city of Bandar Abbas, situated on the shores of the Strait of Hormuz in Persian Baluchistan. -

WB3-Updateposted

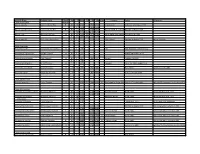

Scientific Name Common Name Book Sex N Mean S.D. Min Max Season Location Source Comments Family Apterygidae Status Apteryx australis Southern Brown Kiwi E M 15 2120 1720 2730 New Zealand Colbourne & Kleinpaste 1983 F 31 2540 2060 3850 Apteryx australis lawryi Southern Brown Kiwi B M 9 2720 2300 3060 Stewart Island, New ZealandMarchant & Higgins 1990 F 10 3115 267 2700 3500 Apteryx rowi Okarito Brown Kiwi N M 49 1924 157 1575 2250 South Island, New Zealand Tennyson et al. 2003 F 51 2650 316 1950 3570 Apteryx mantelli North Island Brown Kiwi N F 4 2725 2060 3433 New Zealand Marchant & Higgins 1990 split in Clements Family Tinamidae Nothocercus julius Tawny-breasted Tinamou N F 1 693 Peru Specimens Mus. SWern Biology Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou N M 1 540 Gomes and Kirwan 2014a Crypturellus brevirostris Rusty Tinamou N M 2 221 209 233 Guyana Robbins et al. 2007 F 1 295 Crypturellus casiquiare Barred Tinamou N F 1 250 Columbia Echeverry-Galvis, unpublished Rhynchotus maculicollis Huayco Tinamou N U 10 868 860 900 Fiora 1933a split by Clements 2008 Tinamotis ingoufi Patagonian Tinamou N U 900 1000 Gomes & Kirwan 2014b Family Spheniscidae Eudyptes moseleyi Tristan Penguin N B 11 2340 517 1400 2950 B Amsterdam Is., Indian OceanDrabek & Tremblay 2000 split from E. chrysocome by Clements 2012 Family Diomedeidae Diomedea antipodensis gibsoni Wandering Albatross N M 35 6800 5500 8600 Auckland Islands Tickell 2000 split by del Hoyo et al. 2013 F 36 5800 4600 7300 Diomedea antipodensis Wandering Albatross N M 10 7460 Antipodes Islands Tickell 2000 split by del Hoyo et al. -

ETHIOPIA: Birding the Roof of Africa

ETHIOPIA: Birding the Roof of Africa A Tropical Birding Set Departure February 12—March 1, 2014 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos taken during this trip by Ken Behrens unless noted otherwise TOUR SUMMARY This was the new version of our set-departure trip, designed to take in virtually all of Ethiopia’s endemics in just 17 days of birding, plus arrival and departure days. Instead of offering the south only as an extension, we have included it in the main tour. This is both because the itinerary makes sense run in this way, and because few people want to miss the birds of the south such as the Prince Ruspoli’s Turaco. This shortened itinerary proved to be very well designed, though definitely fast-paced. We racked up 515 species of birds and 43 mammals in just 17 days of birding. As usual, this haul included virtually all of the Ethiopian and Abyssinian (shared with Eritrea) endemics. Among these, highlights included hefty Blue-winged Goose, elusive Harwood’s Francolin, dapper Spot-breasted Lapwing, stunning White-cheeked and Prince Ruspoli’s Turacos, diminutive Abyssinian Woodpecker, Black-winged Lovebird, Yellow-fronted Parrot, extremely rare Sidamo Lark, nutcracker-like Stresemann’s Bush-Crow, White-tailed Swallow, and melodious songster Abyssinian Catbird. Ethiopia: Birding the ‘Roof’ of Africa Feb. 12-Mar. 1, 2014 But endemics are only part of the picture in Ethiopia. It also offers excellent general African birding, from abundant Palearctic migrants, to Afromontane forest species, to teeming Rift Valley wetlands, to Somali-Masai biome -

Trip Report: Birding and Mammal Watching in Jordan, December 2018

Trip report: Birding and Mammal Watching in Jordan, December 2018 With notes how to see more species in spring, during migration and suggestions for a combination with a visit to Israel Daan Drukker ([email protected]), Ruben Vermeer and Jurriën van Deijk Contents: - Abstract - Introduction - How to use this report - Target species - Itinerary and preparation - Chronological report - How to see more: birds - How to see more: mammals - Literature - Appendix 1: total species list of birds - Appendix 2: total list of all other species that we identified Abstract Trip report about birding and mammal watching in December 2018 in Jordan. We visited the country for 10 days and covered all major hotspots. Due to winter season we missed a lot of species that can potentially be found in Jordan. To make this report as relevant as possible, tables, lists and texts are provided with information about these species in spring or during migration time. Comparisons with the – amongst birders – more popular destination of Israel are also given. Jordan is a wonderful country to observe birds and mammals and we can recommend it to any fanatic birder or mammal watcher, either as a winter break or as a hotspot for migration watching! Best species amongst others: Blanford’s Fox, Striped Hyena, Basalt Wheatear, Crested Honey-Buzzard, Nubian Nightjar, Sinai Rosefinch, Syrian Serin, Dead-Sea Sparrow. Photos by Daan Drukker (DD) and Jurriën van Deijk (JvD), front page: - Basalt Wheatear (DD), between Azraq and Safawi - Blanford’s Fox (JvD), Mujib reserve 2 Introduction Jurriën van Deijk, Ruben Vermeer and I decided to escape the Dutch winter from 5 to 16 December 2018.