Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A8r|Va, 02 Mapuou 2017 Api8|I. Npcoi. /1076 [email protected] Npoz

EAAHNIKH AHMOKPATIA A8r|va, 02 Mapuou 2017 YnOYPFElO YF1OAOMQN KAI METAOOPQN Api8|i. npcoi. YHHPEIIA HOAITIKHZ AEPOF1OPIAZ /1076 TEN1KH AIEYOYNZH AEPOMETAOOPOIM AIEY0YNZH AEPOFIOPIKHZ EKMETAAAEYZHZ TMHMA AIMEPnN AEP/KQN Tax- AiEuQuvGn: T.0. 70360 166.10 nPOZ: 'OTIWI; o nivcucaq nAnpocf>opi£(;: A. BAdxou Ano6EKTU)V (+30J-210-8916149 FAX: (+30J-210-8947132 E-mail: [email protected] 0EMA: npoaKAnan EK6nAwcn<; £V&iacj>epovTO(; 6iKaiu>naTa>v OE KOIVOTLKOUC; a£pO|j.£Ta4>op£Lc; yLa EKTEAEOH aEponopLKcov ypanntov npoq/ano x&pzc, EKTO<; EE. IXET.: (a) EK 847/2004 REpi «5Lanpaynai:euor\<; KCIL e<papnoyr)<; TOJV ou^(puvid)v nepl (6) Yn' api&.: Al/B/28178/2647/19-07-07 (0EKB/1383/03-08-07 KM 2007/C 278/03/21-11-07 EmormnE(f>n^£piSaE.E.) H YnnpEoLa rioALTLKnq A£poTiopLaq pdo£L TCOV SLaTa^ewv TWV avtotEpcx) ava(j)Epon£v(jL)v KavovioLicov TipoaKaAEL iouq KoivoTLKOuq a£po|i£TOt(|>op£L<;, OL OTIOLOL EivaL £yKaT£OTnn£VOL orqv EAAd6a/ va £K6nAcooouv £v6ia4)£pov yLa TO 6LOpLO[i6 Touq npoq EKTsAEaq TaiaLKtov a£poTiopu<tov npoq/ano x^p£c; EKioq E.E. orttoq, KaTd JiEpaiTCoar], A£TiTO[a£pcL)c; £p.c|)aivovTaL orov 0 EV Aoyco filvaKaq nou K£piAan3dv£LTiq Tipoq £K|a£TdAA£uon ypann£t; K<XL OL OXETLKOL KavovLO|iOL, KaLornvETuan^n LoroasALSaTnq YFIA: www.hcaa.gr OTL yLot TOV SLOPLOLIO TWV £v6ia4>£pon£Vtuv a£pop,£Tacf>op£ajv 0a £4>apnoo0ouv TO: KpLTnpiaiou Apepou 5 TOU wq dva) ava4>£po^£vou E0vtKou KavovLOLiou. n^£ponnvia unopoAnq aLTnudTWV, auvo6£uon£vcov ano nAnpn <J>di<£Ao LIE TQ SLKatoAoynTLKd pdo£L TOU Ap6pou 4 TOU ojq dvw E0viKou KavovtoLiOu, opL^ETai n 22a MapTiou 2017. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

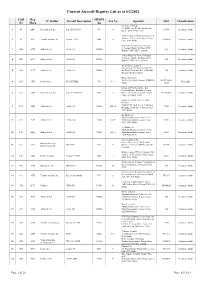

To Access the List of Registered Aircraft As on 2Nd August

Current Aircraft Registry List as at 8/2/2021 CofR Reg MTOM TC Holder Aircraft Description Pax No Operator MSN Classification No Mark /kg Cherokee 160 Ltd. 24, Id-Dwejra, De La Cruz Avenue, 1 41 ABW Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-28-160 998 4 28-586 Aeroplane (land) Qormi QRM 2456, Malta Malta School of Flying Company Ltd. Aurora, 18, Triq Santa Marija, Luqa, 2 62 ACL Textron Aviation Inc. Cessna 172M 1043 4 17260955 Aeroplane (land) LQA 1643, Malta Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 3 1584 ACX Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 544 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 4 1583 ACY Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 582 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Air X Charter Limited SmartCity Malta, Building SCM 01, 5 1589 ACZ Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 4th Floor, Units 401 403, SCM 1001, 590 Aeroplane (land) Ricasoli, Kalkara, Malta Nazzareno Psaila 40, Triq Is-Sejjieh, Naxxar, NXR1930, 001-PFA262- 6 105 ADX Reno Psaila RP-KESTREL 703 1+1 Microlight Malta 12665 European Pilot Academy Ltd. Falcon Alliance Building, Security 7 107 AEB Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-34-200T 1999 6 Gate 1, Malta International Airport, 34-7870066 Aeroplane (land) Luqa LQA 4000, Malta Malta Air Travel Ltd. dba 'Malta MedAir' Camilleri Preziosi, Level 3, Valletta 8 134 AEO Airbus S.A.S. A320-214 75500 168+10 2768 Aeroplane (land) Building, South Street, Valletta VLT 1103, Malta Air Malta p.l.c. -

Official Journal C 137 of the European Union

Official Journal C 137 of the European Union Volume 57 English edition Information and Notices 7 May 2014 Contents II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2014/C 137/01 Non-opposition to a notified concentration (Case M.7200 — Lenovo/IBM x86 Server Business) (1) .... 1 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2014/C 137/02 Euro exchange rates ..................................................................................... 2 2014/C 137/03 Opinion of the Advisory Committee on mergers given at its meeting of 18 January 2013 regarding a draft decision relating to Case COMP/M. 6570 — UPS/TNT Express — Rapporteur: Austria ........... 3 2014/C 137/04 Final Report of the Hearing Officer — UPS/TNT Express (COMP/M.6570) ............................. 4 2014/C 137/05 Summary of Commission Decision of 30 January 2013 declaring a concentration incompatible with the internal market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement (Case COMP/M.6570 — UPS/TNT Express) (notified under document C(2013) 431 final) (1) .................................................. 8 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance 2014/C 137/06 Communication from the Commission concerning the quantity not applied for to be added to the quantity fixed for the subperiod 1 July to 30 September 2014 under certain quotas opened by the Union for products in the poultrymeat, egg and egg albumin sectors .................................. 18 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2014/C 137/07 Publication of decisions by Member States to grant, suspend or revoke operating licenses pursuant to Article 10(3) of Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008 on common rules for the operation of air services in the Community (recast) (1) ............................................................................. -

Travel Information Örnsköldsvik Airport

w v TRAVEL INFORMATION TO AND FROM OER ÖRNSKÖLDSVIK AIRPORT // OVERVIEW Two airlines fly to Örnsköldsvik AirLeap fly from Stockholm Arlanda and BRA-Braathens fly from 1 Stockholm Bromma. 32 flights a week on average Many connections possible via 2 Stockholm’s airports. Örnsköldsvik is located 25 km from the airport, only 20 minutes 3 with Airport taxi or rental car. Book your travel via Air Leap (LPA) www.airleap.se BRA-Braathens Regional 4 Airlines (TF) www.flygbra.se CONNECTIONS WITH 2 AIRLINES GOOD CONNECTIONS good flight connections is essential for good business relationships and Örnsköldsvik Airport fulfills that requirement. As of 2 February, two airlines operate the airport, Air Leap and BRA – Braathens Regional Airlines. Air Leap (IATA code LPA) operates between Örnsköldsvik and Stockholm Arlanda Airport (ARN) and BRA (IATA code TF) between Örnsköldsvik och Stockholm Bromma Airport (BMA). Together the airlines offer on average 32 flights per week, in each direction. air leap operate Saab2000 with 50 Finnair is also a member of ”One minutes flight time to Örnsköldsvik. World Alliance” which gives bene- At Arlanda you find Air Leap at Termi- fits for its members and One World nal 3, with walking distance to Termi- members when travelling on flights nal 2 (SkyTeam, One World airlines) connected to the Finnair Network. and to Terminal 5 (Star Alliance air- Enclosed is a list of some of the lines). Tickets for connecting flights more common connections that are need to be purchased separately and currently possible with one ticket checked luggage brought through and checked in baggade to your customs at Arlanda and checked-in final destination. -

Recommended Best Practices for Commercial Operators

OPERATIONS IN AIRSPACE CLASS E IN GERMANY BELOW FL100 RECOMMENDED BEST PRACTICES FOR COMMERCIAL OPERATORS The following best practices have been developed by flight safety officers and experts to enhance the safety of operations in airspace Class E below FL100 to prevent collisions between controlled and uncontrolled aircraft in a mixed traffic environment. Recommendations for training departments and pilots • IMPROVE AIRSPACE AWARENESS Train pilots to be aware of shortfalls in the existing airspace structure – annual training and NOT only by bulletin using two components: o Generic briefing on airspace Class E in Germany o Dedicated airport briefing documents o Include risk and threats in unprotected airspace in individual departure and arrival briefing • OPERATING RECOMMENDATIONS o FLY DEFENSIVELY! o Maintain Minimum Clean Airspeed or as slow as reasonable o Request to use protected airspace – minimise time in airspace Class E and refuse shortcuts if necessary. Most standard departures and approaches/transitions will facilitate this. o Descend according to airspace structure on arrival. Steep/expedited climb through airspace Class E on departure. o Consider airspace structure for engine out procedures o Consider delaying take-off if conflict with other aircraft is anticipated • USE OF AUTOMATION IN AIRSPACE CLASS ECHO o Minimise visual approaches – they require additional attention and increase flight time in unprotected airspace o Maximise lookout capacity through use of automation (FMS/task sharing) • SEE AND AVOID o Maximise lookout -

Annual Review 2014-2015

The Voice for Business Aviation in Europe Annual Review 2014-2015 Business Aviation in Europe: State of the Industry 2015 Done in collaboration with www.wingx-advance.com www.amstatcorp.com www.eurocontrol.int CONTENTS 03 Introduction 04 Overview • What is Business Aviation? • Sub-divisions of the Definition 05 The European Business Aviation Association • EBAA Representativeness of the Business Aviation Industry • EBAA Membership 1996-2014 07 State of the Industry • Economic Outlook 08 • Traffic Analysis • The European Fleet 09 • Activity Trends by Aircraft Types 10 • Business Aviation Airports 11 • Business Aviation and Safety 12 A Challenging Industry • Challenges from the Inside 1. Means of Booking a Business Aviation Flight 2. Positioning Flights 13 3. Fleet Growth Vs Traffic • Challenges from the Outside 1. Fuel Prices 14 2. Route Charges 15 3. Taxes Revenue per Flight Indicator 16 Looking Ahead: Projects for 2015 • Description of Projects 18 EBAA Members (as of 1 April 2015) 2 INTRODUCTION In our last annual review, looking back at 2013, other sub-sectors were worse off than in 2013 we concluded that 2014 would be a defining (cargo was -0.5%, and charters plummeted moment for Business Aviation. In the first half at -9%). While times remain challenging for all of the year, we saw four consecutive months of forms of transport, we shouldn’t forget that in growth – a breath of fresh air following the years many ways, Business Aviation has fared, and characterised by recession. We were hoping continues to fare, better than most of its air to see that the economic storm was over so transport peers. -

Office of International Aviation (X-40) Foreign and U.S

OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL AVIATION (X-40) FOREIGN AND U.S. CARRIER LICENSING DIVISIONS Page 1 of 4 FOREIGN AIR CARRIER FIFTH FREEDOM CHARTER APPLICATIONS ON HAND DURING WEEK ENDING JUNE 18, 2021 (Prior Approval Required By DOT Regulations (Part 212) and Orders) Points to be Served and Charterer and Applicant Number of Flights Period Requested Action Taken Volga-Dnepr Bangkok-Tampa Loyal Hailiang Copper Withdrawn Airlines 1 o w CARGO 6/10-12-21 6/16/21 Mountain View-Cayenne Space Systems Loral Approved 1 r t CARGO 6/19-25/21 6/17/2021 San Bernardino-Nice Packair Airfreight Inc. Pending 1 o w CARGO 6/27/21-7/1/21 Prestwick-Portsmouth/Everett Boeing Pending 1 o w CARGO 6/25-29/21 Qatar Executive Moscow-Los Angeles LL Jets Approved 1 o w PAX 6/19/21 6/15/21 San Jose-Milan Luna Jets S.A. Approved 1 o w PAX 6/19-20/21 6/15/21 Westchester-Stockholm Sentient Jet Charter Approved 1 o w PAX 6/17-18/21 6/15/21 Teterboro-Moscow LL Jets Approved 1 o w PAX 6/15-17/21 6/15/21 Execaire New Castle-Athens Kuhn Aviation Approved 1 r t PAX 6/19/21-7/1/21 6/17/21 Dallas-Los Cabos Magellan Jets Pending 1 r t PAX 6/23-28/21 FAI rent-a-jet Newark-Al Ain Dept of Health – Abu Dhabi Approved 1 o w PAX 6/14-15/21 6/14/21 Page 2 of 4 FOREIGN AIR CARRIER FIFTH FREEDOM CHARTER APPLICATIONS ON HAND DURING WEEK ENDING JUNE 18, 2021 (Prior Approval Required By DOT Regulations (Part 212) and Orders) Points to be Served and Charterer and Applicant Number of Flights Period Requested Action Taken VistaJet Limited San Francisco-Tel Aviv XO Global Approved 1 o w PAX 6/15/21 6/14/21 -

Norwegian Air Shuttle ASA (A Public Limited Liability Company Incorporated Under the Laws of Norway)

REGISTRATION DOCUMENT Norwegian Air Shuttle ASA (a public limited liability company incorporated under the laws of Norway) For the definitions of capitalised terms used throughout this Registration Document, see Section 13 “Definitions and Glossary”. Investing in the Shares involves risks; see Section 1 “Risk Factors” beginning on page 5. Investing in the Shares, including the Offer Shares, and other securities issued by the Issuer involves a particularly high degree of risk. Prospective investors should read the entire Prospectus, comprising of this Registration Document, the Securities Note dated 6 May 2021 and the Summary dated 6 May 2021, and, in particular, consider the risk factors set out in this Registration Document and the Securities Note when considering an investment in the Company. The Company has been severely impacted by the current outbreak of COVID-19. In a very short time period, the Company has lost most of its revenues and is in adverse financial distress. This has adversely and materially affected the Group’s contracts, rights and obligations, including financing arrangements, and the Group is not capable of complying with its ongoing obligations and is currently subject to event of default. On 18 November 2020, the Company and certain of its subsidiaries applied for Examinership in Ireland (and were accepted into Examinership on 7 December 2020), and on 8 December 2020 the Company applied for and was accepted into Reconstruction in Norway. These processes were sanctioned by the Irish and Norwegian courts on 26 March 2021 and 12 April 2021 respectively, however remain subject to potential appeals in Norway (until 12 May 2021) and certain other conditions precedent, including but not limited to the successful completion of a capital raise in the amount of at least NOK 4,500 million (including the Rights Issue, the Private Placement and issuance of certain convertible hybrid instruments as described further herein). -

Vea Un Ejemplo

3 To search aircraft in the registration index, go to page 178 Operator Page Operator Page Operator Page Operator Page 10 Tanker Air Carrier 8 Air Georgian 20 Amapola Flyg 32 Belavia 45 21 Air 8 Air Ghana 20 Amaszonas 32 Bering Air 45 2Excel Aviation 8 Air Greenland 20 Amaszonas Uruguay 32 Berjaya Air 45 748 Air Services 8 Air Guilin 20 AMC 32 Berkut Air 45 9 Air 8 Air Hamburg 21 Amelia 33 Berry Aviation 45 Abu Dhabi Aviation 8 Air Hong Kong 21 American Airlines 33 Bestfly 45 ABX Air 8 Air Horizont 21 American Jet 35 BH Air - Balkan Holidays 46 ACE Belgium Freighters 8 Air Iceland Connect 21 Ameriflight 35 Bhutan Airlines 46 Acropolis Aviation 8 Air India 21 Amerijet International 35 Bid Air Cargo 46 ACT Airlines 8 Air India Express 21 AMS Airlines 35 Biman Bangladesh 46 ADI Aerodynamics 9 Air India Regional 22 ANA Wings 35 Binter Canarias 46 Aegean Airlines 9 Air Inuit 22 AnadoluJet 36 Blue Air 46 Aer Lingus 9 Air KBZ 22 Anda Air 36 Blue Bird Airways 46 AerCaribe 9 Air Kenya 22 Andes Lineas Aereas 36 Blue Bird Aviation 46 Aereo Calafia 9 Air Kiribati 22 Angkasa Pura Logistics 36 Blue Dart Aviation 46 Aero Caribbean 9 Air Leap 22 Animawings 36 Blue Islands 47 Aero Flite 9 Air Libya 22 Apex Air 36 Blue Panorama Airlines 47 Aero K 9 Air Macau 22 Arab Wings 36 Blue Ridge Aero Services 47 Aero Mongolia 10 Air Madagascar 22 ARAMCO 36 Bluebird Nordic 47 Aero Transporte 10 Air Malta 23 Ariana Afghan Airlines 36 Boliviana de Aviacion 47 AeroContractors 10 Air Mandalay 23 Arik Air 36 BRA Braathens Regional 47 Aeroflot 10 Air Marshall Islands 23 -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Års- Och Hållbarhetsredovisning 2020

Års- och hållbarhetsredovisning 2020 Verksamhet Finansiell information Året i korthet 4 Förvaltnings berättelse 82 Det här är Swedavia 5 Utdelning och vinstdisposition 87 Styrelseordförande har ordet 6 Bolagsstyrningsrapport 88 Vd har ordet 8 Styrelse 94 Pandemins påverkan 10 Koncernledning 96 Marknad och trender 14 Koncernens räkenskaper 98 Så skapar Swedavia värde 18 Koncernens resultaträkning 98 Swedavias strategier 20 Koncernens balansräkning 99 Samarbeten 22 Koncernens förändringar i eget kapital 101 Verksamhet 23 Koncernens kassaflödesanalys 102 Flygplatsverksamhet 24 Moderbolagets räkenskaper 103 Stockholm Arlanda Airport 24 Moderbolagets resultaträkning 103 Göteborg Landvetter Airport 26 Moderbolagets balansräkning 104 Bromma Stockholm Airport 28 Moderbolagets förändringar i eget kapital 105 Sju regionala flygplatser 29 Moderbolagets kassaflödesanalys 106 Linjer och destinationer 30 Noter 107 Aviation Business 32 Årsredovisningens undertecknande 141 Commercial Services 34 Revisions berättelse 142 Fastighetsverksamhet 36 Real Estate 36 Framtidens hållbara flygplatser och flygtransporter 38 Framtidens hållbara flygplatser 40 Swedavias övergripande mål 40 Sociala förhållanden och personal 42 Antikorruption och mänskliga rättigheter 46 Hälsa och säkerhet 48 Ekonomisk utveckling och investeringar 50 Masterplan 52 Leverantörer 53 Klimat och miljö 54 Detta är Swedavias års- och hållbarhetsredovisning för räkenskapsåret 2020. Rapporten vänder sig framför allt till ägare, kunder, kredit analytiker Framtidens hållbara flygtransporter 58