FAA Forecast Accuracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business & Commercial Aviation

BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION LEONARDO AW609 PERFORMANCE PLATEAUS OCEANIC APRIL 2020 $10.00 AviationWeek.com/BCA Business & Commercial Aviation AIRCRAFT UPDATE Leonardo AW609 Bringing tiltrotor technology to civil aviation FUEL PLANNING ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Part 91 Department Inspections Is It Airworthy? Oceanic Fuel Planning Who Says It’s Ready? APRIL 2020 VOL. 116 NO. 4 Performance Plateaus Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent. You may not modify, publish, license, transmit (including by way of email, facsimile or other electronic means), transfer, sell, reproduce (including by copying or posting on any network computer), create derivative works from, display, store, or in any way exploit, broadcast, disseminate or distribute, in any format or media of any kind, any of the Digital Material, in whole or in part, without the express prior written consent of Informa. -

Business Opportunities in Aircraft Cabin Conversion and Refurbishing

Business Opportunities in Aircraft Cabin Conversion and Refurbishing Mihaela F. Niţă1 and Dieter Scholz2 Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Berliner Tor 9, 20099 Hamburg, Germany This paper identifies several meaningful business opportunity cases in the area of aircraft cabin conversion and refurbishing and predicts the market volume and the world distribution for each of them: 1.) international cabins, 2.) domestic cabins, 3.) aircraft on operating lease, 4.) freighter conversions and 5.) VIP completions. This implies the determination of cabin modification/conversion scenarios, along with their duration and frequency. Factors driving the cabin conversion and refurbishing are identified. Several aircraft databases, containing the current world feet as well as the forecasted fleet for the next years, are analyzed. The results are obtained by creating a program able to read and analyze the gathered data. It is shown that about 38000 cabin redesigns will be undertaken within the next 20 years. About 2500 conversions from jetliners into freighters and 25000 cabin modifications at VIP standards will emerge on the market. The North American and European markets will keep providing good business opportunities in this area. The Asian market, however, is growing fast, and its very strong influence on demand puts it in the front rank for the next 20 years. Nomenclature agescenario_limit = aircraft age for which the refurbishing is no longer planned by the operator. dateaircraft_delivery = date of the aircraft first delivery datemodification -

Design of a Light Business Jet Family David C

Design of a Light Business Jet Family David C. Alman Andrew R. M. Hoeft Terry H. Ma AIAA : 498858 AIAA : 494351 AIAA : 820228 Cameron B. McMillan Jagadeesh Movva Christopher L. Rolince AIAA : 486025 AIAA : 738175 AIAA : 808866 I. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Mr. Carl Johnson, Dr. Neil Weston, and the numerous Georgia Tech faculty and students who have assisted in our personal and aerospace education, and this project specifically. In addition, the authors would like to individually thank the following: David C. Alman: My entire family, but in particular LCDR Allen E. Alman, USNR (BSAE Purdue ’49) and father James D. Alman (BSAE Boston University ’87) for instilling in me a love for aircraft, and Karrin B. Alman for being a wonderful mother and reading to me as a child. I’d also like to thank my friends, including brother Mark T. Alman, who have provided advice, laughs, and made life more fun. Also, I am forever indebted to Roe and Penny Stamps and the Stamps President’s Scholarship Program for allowing me to attend Georgia Tech and to the Georgia Tech Research Institute for providing me with incredible opportunities to learn and grow as an engineer. Lastly, I’d like to thank the countless mentors who have believed in me, helped me learn, and Page i provided the advice that has helped form who I am today. Andrew R. M. Hoeft: As with every undertaking in my life, my involvement on this project would not have been possible without the tireless support of my family and friends. -

A Conceptual Design of a Short Takeoff and Landing Regional Jet Airliner

A Conceptual Design of a Short Takeoff and Landing Regional Jet Airliner Andrew S. Hahn 1 NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, VA, 23681 Most jet airliner conceptual designs adhere to conventional takeoff and landing performance. Given this predominance, takeoff and landing performance has not been critical, since it has not been an active constraint in the design. Given that the demand for air travel is projected to increase dramatically, there is interest in operational concepts, such as Metroplex operations that seek to unload the major hub airports by using underutilized surrounding regional airports, as well as using underutilized runways at the major hub airports. Both of these operations require shorter takeoff and landing performance than is currently available for airliners of approximately 100-passenger capacity. This study examines the issues of modeling performance in this now critical flight regime as well as the impact of progressively reducing takeoff and landing field length requirements on the aircraft’s characteristics. Nomenclature CTOL = conventional takeoff and landing FAA = Federal Aviation Administration FAR = Federal Aviation Regulation RJ = regional jet STOL = short takeoff and landing UCD = three-dimensional Weissinger lifting line aerodynamics program I. Introduction EMAND for air travel over the next fifty to D seventy-five years has been projected to be as high as three times that of today. Given that the major airport hubs are already congested, and that the ability to increase capacity at these airports by building more full- size runways is limited, unconventional solutions are being considered to accommodate the projected increased demand. Two possible solutions being considered are: Metroplex operations, and using existing underutilized runways at the major hub airports. -

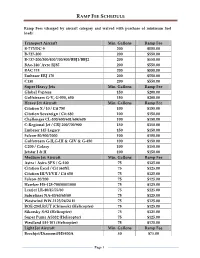

Ramp Fee Schedule

RAMP FEE SCHEDULE Ramp Fees (charged by aircraft category and waived with purchase of minimum fuel load): Transport Aircraft Min. Gallons Ramp Fee B-717/DC-9 200 $550.00 B-727-200 200 $550.00 B-737-200/300/400/700/800/BBJ1/BBJ2 200 $550.00 BAe-146/ Avro RJ85 200 $550.00 BAC 111 200 $550.00 Embraer ERJ 170 200 $550.00 C130 200 $550.00 Super Heavy Jets Min. Gallons Ramp Fee Global Express 150 $200.00 Gulfstream G-V, G-550, 650 150 $200.00 Heavy Jet Aircraft Min. Gallons Ramp Fee Citation X / 10 / Cit 750 100 $150.00 Citation Sovereign / Cit 680 100 $150.00 Challenger CL-300/600/601/604/605 100 $150.00 C-Regional Jet / CRJ 200/700/900 150 $150.00 Embraer 145 Legacy 150 $150.00 Falcon-50/900/2000 100 $150.00 Gulfstream G-II,G-III & GIV & G-450 100 $150.00 G200 / Galaxy 100 $150.00 Jetstar I & II 100 $150.00 Medium Jet Aircraft Min. Gallons Ramp Fee Astra / Astra SPX / G-100 75 $125.00 Citation Excel / Cit 560XL 75 $125.00 Citation III/VI/VII / Cit 650 75 $125.00 Falcon-20/200 75 $125.00 Hawker HS-125-700/800/1000 75 $125.00 Learjet LR-40/45/55/60 75 $125.00 Sabreliner NA-40/60/65/80 75 $125.00 Westwind WW-1123/24/24 II 75 $125.00 BOE-234LR/UT (Chinook) (Helicopter) 75 $125.00 Sikorsky S-92 (Helicopter) 75 $125.00 Super Puma AS332 (Helicopter) 75 $125.00 Westland EH-101 (Helicopter) 75 $125.00 Light Jet Aircraft Min. -

Global Fleet & Mro Market Forecast Summary

GLOBAL FLEET & MRO MARKET FORECAST SUMMARY 2017-2027 AUTHORS Tom Cooper, Vice President John Smiley, Senior Manager Chad Porter, Technical Specialist Chris Precourt, Technical Analyst For over a decade, Oliver Wyman has surveyed aviation and aerospace senior executives and industry influencers about key trends and challenges across the Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul market. If you are responsible for maintenance and engineering activities at a carrier, aftermarket activities at an OEM, business operations at an MRO, or a lessor, you may want to participate in our survey. For more information, please contact our survey team at: [email protected]. To read last year’s survey, please see: http://www.oliverwyman.com/our-expertise/insights/2016/apr/mro-survey-2016.html . CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2. STATE OF THE INDUSTRY 5 Global Economic Outlook 7 Economic Drivers 11 3. FLEET FORECAST 17 In-Service Fleet Forecast 18 4. MRO MARKET FORECAST 31 Copyright © Oliver Wyman 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Oliver Wyman’s 2017 assessment and 10-year outlook for the commercial airline transport fleet and the associated maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) market marks the 17th year of supporting the industry with informed, validated industry data. This has become the most credible go-to forecast for many executives in the airline and MRO industry as well as for those with financial interests in the sector, such as private equity firms, investment banks and investment analysts. The global airline industry has made radical changes in the last few years and is producing strong financial results. While the degree of success varies among the world regions, favorable fuel prices and widespread capacity discipline are regarded as key elements in the 2016 record high in global profitability ($35.6 billion). -

Disrupting the Business Jet: but How? by Ryan S

Disrupting the Business Jet: But How? By Ryan S. Wood Founder and CEO Frontline Aerospace, Inc Blu from Movie: RIO Just Keep It Simple Overall Aircraft Efficiency 휂 Thermal X 휂 Propulsive Disrupting Engine Performance • Problem is cooling! • Solution go full compressor flow cooling Overall Efficiency = Propulsive x Thermal Ducted Business Fan Jets Drag: Boundary Layer Ingestion (BLI) • drag reduction of 8.6% Source: AIAA Paper: Boundary Layer Ingestion Benefit of the D8 Transport Aircraft. August 24, 2017 SkyFan: Here Is One Way to Disrupt Joined Wing: Weight-Drag Reduction • 5X less bending moment at root • Less drag • Lighter wing Landing Zone Flexibility—Paved Runways •Save Time Business Jets •Get Closer to SkyFan business • Others SkyFan Reaches 2X the airports •Why? Fan thrust to weight ratio Source: CIA Factbook 2010, Top 30 Countries, Paved Runways, 11,441 Fuel Cost per Seat Mile SkyFan is as fuel efficient as Boeing 737-MAX, some 5X competitors SkyFan Circle Range Map (4 pax 5200 nmi) Challenger 350 Gulfstream G280 SkyFan SkyFan Noise Reduction •Engines inside fuselage •Intake/exhaust cowlings •Noise absorbing ducts Electronic Aircraft Window - PanDow Cameras driving internal 8K monitors GE CT7/T700 Engine • 22,000 built • 100 million flight hours • Global MRO • Upgrades Pending Intellectual Property (IP) •SkyFan Utility Patent •Engine drive ducted fan propulsion •Engine Isothermal compression (2) SkyFan Performance Metric Comparison SkyFan • Pick any set of metrics • Thrill index= (thrust/weight) • Aircraft Total Value= Bus Jets S*R*P*Airports/DOC* TOGW*Purchase Price Determining Market Demand—Mee Inc How to Price SkyFan? SkyFan Market Demand Curve – Mee Inc. -

Conceptual Design of a Business Jet Aircraft

International Conference on Mechanical, Industrial and Energy Engineering 2014 25-26 December, 2014, Khulna, BANGLADESH ICMIEE-PI-14035310 CONCEPTUAL DESIGN OF A BUSINESS JET AIRCRAFT Jannatun Nawar 1,*, Nafisa Nawal Probha 2 Adnan Shariar 3, Abdul Wahid4, Saifur Rahman Bakaul5 1,2,3,4 Student, Department of Aeronautical Engineering, Military Institute of Science & Technology, Dhaka-1216, 5 Associate Professor , Department of Aeronautical Engineering, Military Institute of Science & Technology, Dhaka-1216, ABSTRACT The modern jet transport is considered as one of the finest integration of technologies. Its economic success depends on performance, low maintenance costs and high passenger appeal and design plays a vital role in summing up all these factors. Conceptual design is the first step to design of an aircraft. In this paper a business jet aircraft is designed to carry 8 passengers and to cover a range of 2000 NM with maximum Mach No of 0.7 and with maximum ceiling of 29,000 ft. The conceptual design consisted of initial sizing, aerodynamics and performance analysis. Through trade studies and comparison with other business jet aircrafts a final model of the aircraft was built to achieve the requirements. Key Words: Business jet, Conceptual design, Initial Sizing, Aerodynamics, Aircraft performance, Trade study. 1. Introduction Airplane design is an art with scientifically approach. It requires both the intellectual engineering and ngiseD ygolDchceT cDogne sensible assumptions. Aircraft design is actually sgnesegigDei ytbshbashseT hcgeol done to meet certain specifications and requirements established by potential users or pioneer innovative, new ideas and technology. Now-a-days business jet aircraft is one of the most popular forms of transport aircraft. -

Chapter Iv Regionals/Commuters

CHAPTER IV REGIONALS/COMMUTERS For purposes of the Federal Aviation REVIEW OF 20032 Administration (FAA) forecasts, air carriers that are included as part of the regional/commuter airline industry meet three criteria. First, a The results for the regional/commuter industry for regional/commuter carrier flies a majority of their 2003 reflect the continuation of a trend that started available seat miles (ASMs) using aircraft having with the events of September 11th and have been 70 seats or less. Secondly, the service provided by drawn out by the Iraq War and Severe Acute these carriers is primarily regularly scheduled Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). These “shocks” to passenger service. Thirdly, the primary mission of the system have led to the large air carriers posting the carrier is to provide connecting service for its losses in passengers for 3 years running. The code-share partners. losses often reflect diversions in traffic to the regional/commuter carriers. These carriers During 2003, 75 reporting regional/commuter recorded double-digit growth in both capacity and airlines met this definition. Monthly traffic data for traffic for the second time in as many years. History 10 of these carriers was compiled from the has demonstrated that the regional/commuter Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Form 41 industry endures periods of uncertainty better than and T-100 filings. Traffic for the remaining the larger air carriers. During the oil embargo of 65 carriers was compiled solely from T-100 filings. 1 1973, the recession in 1990, and the Gulf War in Prior to fiscal year 2003, 10 regionals/commuters 1991, the regional/commuter industry consistently reported on DOT Form 41 while 65 smaller outperformed the larger air carriers. -

Designing a Very Light Jet

GadShannan DESIGN Akademin för Innovation, Design och Teknik Designing a Very Light Jet Master thesis work 30 credits, D-level Product and process development, concurrent engineering Master Thesis Programme Innovation and Product Design Per Nyblom Report code: IDPPOPEXD:08:11 Commissioned by: GadShaanan DESIGN Tutor (company): Mladen Barbaric Tutor (university): Ragnar Tengstrand Examiner: Rolf Lövgren Abstract Introduction Very light jet is a hot subject growing stronger and stronger. The new type of air craft is an air plane that weighs less than 10000 pounds and uses a jet engine. Problem The student was proposed to designing a conceptual very light jet that could be used for inspiration and accepted the challenge. Method In this thesis the reader can follow the project progress in detail, the proposed methods and the results. The student divided the project into four activities analysis, creation, development and documentation. Result The project ended with a concept very light jet with simple specifications. Illustrations for inspirational usage and a simulation testing for verification of the proposed concept specifications. Keywords: Nm 1 nautical miles = 1.852 kilometres lb 1 pound = 0.45359237 kilograms ft 1 foot = 0.3048 metres in 1 inch = 0.025 metres MTOW Maximum take-off weight Pax Available Seats in an airplane both crew and traveller VLJ (micro jet) Very Light Jet, coined expression. FAA Federal Aviation Administration, www.faa.gov EASA European Aviation Safety Agency, www.easa.eu.int CAA Civil Aviation Authority PDF File format standard Intelligence Information that is presented easy to act on. Thrust Power given by a jet engine measured in pounds. -

Technological Innovation in the Airline Industry: the Impact of Regional Jets

Technological Innovation in the Airline Industry: The Impact of Regional Jets by Jan K. Brueckner Department of Economics University of California, Irvine 3151 Social Science Plaza Irvine, CA 92697 e-mail: [email protected] and Vivek Pai Department of Economics University of California, Irvine 3151 Social Science Plaza Irvine, CA 92697 e-mail: [email protected] February 2007 Abstract This paper explores the impact of the regional jet (RJ), an important new technological inno- vation in the airline industry, on service patterns and service quality. The evidence shows that RJs were used to provide service on a large number of new hub-and-spoke (HS) and point-to- point (PP) routes. In addition, they replaced discontinued jet and turboprop service on many HS routes, as well as supplementing continuing jet service on such routes. When replace- ment or supplementation by RJs occurred, passengers benefited from better service quality via higher flight frequencies. The paper’s theoretical analysis predicts that the frequency ad- vantage of RJs over jets, a consequence of their small size, should have led to the emergence of PP service in thin markets where such service was previously uneconomical. However, the evidence contradicts this prediction, showing that markets attracting new PP service by RJs had demographic characteristics similar to those of markets that already had jet PP service or attracted it after 1996. Technological Innovation in the Airline Industry: The Impact of Regional Jets by Jan K. Brueckner and Vivek Pai 1. Introduction While the airline industry has experienced a number of significant institutional innovations over the years, including the adoption of hub-and-spoke networks and frequent flier programs and the use of yield management techniques, true technological innovations have been less fre- quent. -

Aviation Activity Forecasts

2 Aviation Activity Forecasts INTRODUCTION The Charles M. Schulz–Sonoma County Airport (STS) is one of six public use airports in Sonoma County. It is the only commercial service airport1 between the San Francisco Bay Area to the south, Sacramento to the east and Arcata-Eureka to the north. The Airport’s primary service area has a population of over 1 million people2 and includes Sonoma, Lake, and Mendocino counties, and parts of Marin and Napa counties. Airport Role The Sonoma County Airport, as the region’s principal Airport, serves many roles, including providing facilities for scheduled commuter and air carrier airline services. The California Aviation System Plan (CASP) designates the Airport as a Primary Commercial Service Non-Hub Airport. There are no Primary Commercial Service Hub airports in the region. The closest Primary Commercial Service Hub airports are the San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose International Airports. The Sacramento International Airport is slightly more distant, but at times it can be more convenient for highway travel. The Sonoma County Airport also serves a growing population of general aviation (GA) activities including corporate and business flying. For this reason, the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS) currently classifies the Airport as a General Aviation facility, but in the future the Airport is expected to be reclassified as a Commercial Service Non-Primary Airport. A strong potential exists for additional scheduled airline and commuter air carrier service, particularly in the form of new, quiet technology jet aircraft with up to 135 passenger seats.3 The Airport also serves as a base of operations for local pilots, a place to conduct business, and a point of emergency access for the region.