A New Creation on Earth: Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mother Mirra Alfassa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mother India

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE Vol. LX No. 6 “Great is Truth and it shall prevail” CONTENTS Sri Aurobindo SELF (Poem) ... 421 THE SCIENCE OF CONSCIOUSNESS ... 422 The Mother ‘NO ERROR CAN PERSIST IN FRONT OF THEE’ ... 426 THE POWER OF WORDS ... 427 Amal Kiran (K. D. Sethna) “SAKUNTALA” AND “SAKUNTALA’S FAREWELL”—CORRESPONDENCE WITH SRI AUROBINDO ... 429 Priti Das Gupta MOMENTS, ETERNAL ... 435 Arun Vaidya AN ETERNAL DREAM ... 440 Prabhjot Kulkarni WHO AM I (Poem) ... 447 S. V. Bhatt PAINTING AS SADHANA: KRISHNALAL BHATT (1905-1990) ... 448 Narad (Richard Eggenberger) TEHMI-BEN—NARAD REMEMBERS ... 456 Sitangshu Chakrabortty LORD AND MOTHER NATURE (Poem) ... 464 Bibha Biswas THE BIRTH OF “BATIK WORK” ... 465 Prithwindra Mukherjee BANKIMCHANDRA CHATTERJEE ... 468 Chunilal Chowdhury A WORLD WITHOUT WAR ... 476 Prema Nandakumar DEVOTIONAL POETRY IN TAMIL ... 480 Pujalal NAVANIT STORIES ... 490 421 SELF He said, “I am egoless, spiritual, free,” Then swore because his dinner was not ready. I asked him why. He said, “It is not me, But the belly’s hungry god who gets unsteady.” I asked him why. He said, “It is his play. I am unmoved within, desireless, pure. I care not what may happen day by day.” I questioned him, “Are you so very sure?” He answered, “I can understand your doubt. But to be free is all. It does not matter How you may kick and howl and rage and shout, Making a row over your daily platter. “To be aware of self is liberty. Self I have got and, having self, am free.” SRI AUROBINDO (Collected Poems, SABCL, Vol. -

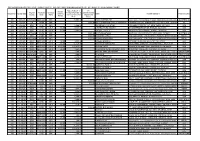

Foreign Contribution Report

SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM TRUST PONDICHERRY FOREIGN CONTRIBUTION DONORS LIST OCTOBER-20 TO DECEMBER-20(Q3) Rupee Value of ( FC Foreign Original Payment Currency Foreign Chqs/ DDs & Donation(Cash) Receipt No F Receipt Date Currency Name Present Address-1 Present Country Country mode Name Currency Notes )1st (Rupees) 1st Amount Recp. Recpt 300 1-10-20 AUSTRALIA NEFT HDFC INR 5,308.00 RAJIV RATTAN DR GRATITUDE, 159 BOUNDARY ROAD, WAHROONGA, NSW-2076 AUSTRALIA 301 2-10-20 UK CASH INR 1,000.00 SRI AUROBINDO CIRCLE(ASHRAM) 8 SHERWOOD AVE., STREATHAM VALE, SW16 5EW, LONDON UK 302 2-10-20 USA CHQ INR 6,000.00 AURINDAK K GHATAK 455 MAIN STREET # 16F, NEW YORK, NY-10044 USA 303 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 100.00 7,231.00 CHITRALEKHA GHOSH 22 INDEPENDENCE DR, EDISON, NJ-08820 USA 304 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 101.00 7,303.00 SATISH J PATEL 1413 BRYS DR, GROSSE POINTE, MI-48236 USA 305 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,001.00 R VISWANATHAN UNIT-330, 298 SUSSEX ST, NSW-2000, SYDNEY AUSTRALIA 306 2-10-20 USA CASH INR 1,000.00 RICHARD HARTZ C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 307 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,000.00 SUSAN CROTHERS C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 308 2-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 50.00 3,685.25 DINESH MANDAL 1013 ROYAL STOCK LN, CARY, NC-27513 USA 309 2-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 205.00 15,127.46 VIJAYA CHINNADURAI 1739 STIFEL LANE DR, CHESTERFIELD, MO-63017 USA 310 3-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 5,000.00 3,65,425.00 KUSUM PATEL 1694 HIDDEN OAK TRAIL,MANSFIELD, OH-44906 USA 311 3-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 20.00 1,461.70 RAMAKRISHNAN -

Essays in Philosophy and Yoga

13 Essays in Philosophy and Yoga VOLUME 13 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1998 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Essays in Philosophy and Yoga Shorter Works 1910 – 1950 Publisher's Note Essays in Philosophy and Yoga consists of short works in prose written by Sri Aurobindo between 1909 and 1950 and published during his lifetime. All but a few of them are concerned with aspects of spiritual philosophy, yoga, and related subjects. Short writings on the Veda, the Upanishads, Indian culture, politi- cal theory, education, and poetics have been placed in other volumes. The title of the volume has been provided by the editors. It is adapted from the title of a proposed collection, ªEssays in Yogaº, found in two of Sri Aurobindo's notebooks. Since 1971 most of the contents of the volume have appeared under the editorial title The Supramental Manifestation and Other Writings. The contents are arranged in ®ve chronological parts. Part One consists of essays published in the Karmayogin in 1909 and 1910, Part Two of a long essay written around 1912 and pub- lished in 1921, Part Three of essays and other pieces published in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1921, Part Four of an essay published in the Standard Bearer in 1920, and Part Five of a series of essays published in the Bulletin of Physical Education in 1949 and 1950. Many of the essays in Part Three were revised slightly by the author and published in small books between 1920 and 1941. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Topic for Dissertation MA Philosophy Semester

Topic for Dissertation M.A. Philosophy Semester - IV(CBCS) 2017-18 1. The epistemological issues embedded in the skeptical challenge to knowledge as found in Indian tradition. Select Bibliography: Original Sources: Vigrahavyavartani of Nagarjuna Tattopaplvasinha of Jayarashi Bhatta Khandanakhandakhadya of Shriharsha Other sources: ―Lokayata/ Carvaka: A Philosophical Study‖ by Dr. Gokhale Pradip, OUP, 2015 ‗Philosophy, Culture and Religion: Essays by B.K. Matilal‘, Jonardon Ganeri (Ed.) Oxford University Press, Delhi, 2002. 2. The debate between the Realists and the Constructivists in the Context of Indian Epistemology Select Bibliography: Gillon Brebdan S. (Ed.), ‗Logic in Earliest Classical India‘, Motilal Banarasidas, New Delhi, 2010. Bhattacharya H.M. `Jaina Logic and Epistemology‘, K.P. Bagchi &Co., Calcutta, 1994. Popper Karl, `Conjectures and Refutations‘, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1963 Shastri D.N. ―Critique of Indian Realism‖, Bharatiya Vidya Prakashan, 1972. Ayer A.J. `Problem of Knowledge‘, MacMillan, London, 1965. 3. Anekantavada as a paradigm for solving the philosophical issues: A Critical Study Select Bibliography: ‗Aptamimamsa: A Critique of an Authority‘, Editor, Dr. Nagin Shah Pub. Sanskrit- Sanskriti Granthamala, Ahmadabad, 1999. ‗The Central Philosophy of Jainism (Anekantavada)‘, Matilal B.K pub. L.D. Institute of Indology, Ahmadabad, 1981. Tattvartha Sutra,Commen. By Pt. Sukhlalji, Tr.Dixit, K.K. Pub. L.D. Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad, 2000. Harmaless Souls, Johnson, W.J., Motilal Banarasidas Pub. Delhi, 1995. Jaina Path of Purification, Jaini Padmanabh, Motilal Banarasidas, Delhi, 1979 1 Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Glasenapp, Helmuth Von, Eng. Trans. Shridhar Shrotri, Motilal Banarasidas Pub. Delhi,1999 Lectures on Jainism, Dr. Tatia, Nathmal , Pub. By Department of Jainology, University of Madras, 1998 4. -

Institute of Human Study Hyderabad

A Journal of Integral and Future Studies Published by Institute of Human Study Hyderabad Volume IVi Issue II Volume IV Issue II NEW RACE is published by Chhalamayi Reddy on behalf of Institute of Human Study, 2-2-4/1, O.U.Road, Hyderabad 500 044. Founder Editor : (Late) Prof. V. Madhusudan Reddy Editor-in-Chief: V. Ananda Reddy Assistant Editor: Shruti Bidwaikar Designing: Vipul Kishore Email: [email protected]; Phone: 040 27098414 On the web: www.instituteofhumanstudy.org ISSN No.: 2454–1176 ii Volume IV Issue II NEW RACE A Journal of Integral & Future Studies August 2018 Volume IV Issue 2 CONTENTS From the Editor's Desk... Section II: Beauty and Delight 36 Shruti Bidwaikar iv Beauty in Women Sri Aurobindo 37 Section I: Truth 1 Laxmiben Patel’s Work Swami Vivekananda: with the Mother “A Soul of Puissance” Deepshikha Reddy 39 Sri Aurobindo 2 The First Flight... (a sketch) “I had some Strange Power” Deepshikha Reddy 42 Swami Vivekananda 4 Towards a Theory of Poetic Creation Sri Aurobindo: Vinod Balakrishnan 43 Bridge between the Section III: Life 47 Past and the Future The Finnish Education Model: M. P. Pandit 7 In the Light of the Mother’s Essays on Education Significance of Sridarshan Koundinya 48 Sri Aurobindo’s Relics Self-Determination and Ananda Reddy 15 the Path Ahead Evolution Next Kisholoy Gupta 53 Alok Pandey 26 Coming in the Clasp of Divine Grace Search for the Unity of Dolan 57 Matter and Energy Sketches of Life Narendra Joshi 31 Oeendrila Guha 59 iii Volume IV Issue II From the Editor's Desk.. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

July 2017 Special Issue Introduction

July 2017 Special Issue Volume 13, No 1 Integral Education, Women’s Spirituality and Integral Feminist Pedagogies Table of Contents Special Issue Introduction ......................................................................... 1 Bahman Shirazi The Modern Knowledge Academy, Vedantic Education and Integral Education ................................................................................................... 5 Debashish Banerji A Complete Integral Education: Five Principal Aspects ........................ 20 Jeremie Zulaski The Value of an Integral Education: A Mixed-Method Study with Alumni of the East-West Psychology Program at the California Institute of Integral Studies ................................................................................... 30 Heidi Fraser Hageman Women’s Spirituality at CIIS: Uniting Integral and Feminist Pedagogies ................................................................................................................. 62 Alka Arora cont'd next page The Divine Feminist: A Diversity of Perspectives That Honor Our Mothers’ Gardens by Integrating Spirituality and Social Justice ........... 72 Arisika Razak The Borderlands Feminine: A Feminist, Decolonial Framework for Re- membering Motherlines in South Asia/Transnational Culture ............... 87 Monica Mody Chinmoyee and Mrinmoyee .................................................................... 99 Karabi Sen July 2017 Special Issue Introduction Issue Editor: Bahman A. K. Shirazi1 The focus of this special issue of Integral Review -

Sri Aurobindo's Formulations of the Integral Yoga Debashish Banerji California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, USA

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 37 | Issue 1 Article 6 9-1-2018 Sri Aurobindo's Formulations of the Integral Yoga Debashish Banerji California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, USA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Banerji, D. (2018). Sri Aurobindo's formulations of the integral yoga. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 37 (1). http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2018.37.1.38 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sri Aurobindo's Formulations of the Integral Yoga Debashish Banerji California Institute of Integral Studies San Francisco, CA, USA Sri Aurobindo Ghose (1872–1950) developed, practiced and taught a form of yoga, which he named integral yoga. If one peruses the texts he has written pertaining to his teaching, one finds a variety of models, goals, and practices which may be termed formulations or versions of the integral yoga. This article compares three such formulations, aiming to determine whether these are the same, but in different words, as meant for different audiences, or whether they represent different understandings of the yoga based on changing perceptions. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Download Book

TEXT FLY WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY J< OU_1 58876 >[g Publishers: SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM PONDICHERRY All rights reserved First Edition, November 1940 Second Edition, March 1947 Third Edition, January 1955 SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM PRESS PONDICHERRY PRINTED IN INDIA 1025/12/54/1500 CONTENTS Page L BANDE MATARAM .... i II. RISHI . BANKIM CHANDRA . 7 III. BAL GANGADHAR TILAK ... 14 IV. DAYANANDA (i) The Man and His Wosk . 39 xXii) Dayananda and the Veda . 48 V. THE MEN THAT PASS . , 6r PUBLISHER'S NOTE Our acknowledgements are due to Messrs. Gancsh & Go, and to the Editor of the Vcdic Magazine for permission to reprint the appreciation of Tilak, which was written as a foreword to the Speeches of Bal Gangadhar Tilak and the articles on Dayananda. BANKIM-TILAK-DAYANANDA BANDE MATARAM (Original Bengali in Devanagri Character) -^^ Ptd II BANKIM TILAK DAYANANDA gfir *TT frf ^TT'ff Hld<H II BANDE MATARAM (Translation} Mother, I bow to thee! Rich with thy hurrying streams. Bright with thy orchard gleams. Cool with thy winds of delight, Dark fields waving. Mother of might, Mother free. Glory of moonlight dreams, Over thy branches and lordly streams, Clad in thy blossoming trees, Mother, giver of ease, Laughing low and sweet! Mother, I kiss thy feet, Speaker sweet and low! Mother, to thee I bow. Who hath said thou art weak in thy lands, When the swords flash out in twice seventy million hands And seventy million voices roar Thy dreadful name from shore to shore? With many strengths who art mighty and stored, BANKIM TILAK DAYANANDA To thee I call. -

Yoga As a Part of Sanātana Dharma

Gejza M. Timčák Yoga as a Part of Sanātana Dharma The definition of religion is not easy as the views on this point Received December 12, 2018 are very different. The Indian Sanātana Dharma, the “Eternal Revised March 18, 2019 Accepted March 23, 2019 Order”, is how Indians call their system that has also a connotation that relates to what we call religion. What we understand as Yoga was defined by Patañjali, Svātmārāma, Gorakhnath, and other Yoga masters. Yoga is a part of Sanātana Dharma and is Key words Yoga, vedic religion, called Mukti Dharma, the “Dharma of Liberation”. Yoga as one Hinduism, Sanātana Dharma of the six orthodox philosophies is free from religious traits. The difference between the Indian and Western understanding of Sanātana Dharma is investigated from a practical point of view reflected in the literature and in a dialogue with Indian pandits. The reflection of the Western (namely Christian) understanding of Indian Sanātana Dharma and its effect on the way how Christians look at Yoga is also mentioned. 24 Spirituality Studies 5-1 Spring 2019 GEJzA M. TIMčáK 1 Introduction The topic of Yoga and its relation to religion are an issue that is a matter of discussion for some time. For some, religion and darshan, “philosophy”, are nearly synonyms, for some they are not. The concept of “Hindu religion” [1] – as will be shown later – is also a relatively vague concept, but this is how in the West and now also in the East, the Brahmanic tradition [2], plus the six philosophical darshans are often called.