Download Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo Ghosh

UNIT 6 HINDUISM : SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND SRI AUROBINDO GHOSH Structure 6.2 Renaissance of Hi~~duis~iiand the Role of Sri Raniakrishna Mission 0.3 Swami ViveItananda's Philosopliy of Neo-Vedanta 6.4 Swami Vivckanalida on Nationalism 6.4.1 S\varni Vivcknnnnda on Dcrnocracy 6.4.2 Swami Vivckanar~daon Social Changc 6.5 Transition of Hinduism: Frolii Vivekananda to Sri Aurobindo 6.5. Sri Aurobindo on Renaissance of Hinduism 6.2 Sri Aurol>i~ldoon Evil EffLrcls of British Rulc 6.6 S1.i Aurobindo's Critique of Political Moderates in India 6.6.1 Sri Aurobilido on the Essencc of Politics 6.6.2 SI-iAurobindo oil Nationalism 0.6.3 Sri Aurobindo on Passivc Resistance 6.6.4 Thcory of Passive Resistance 6.6.5 Mcthods of Passive Rcsistancc 6.7 Sri Aurobindo 011 the Indian Theory of State 6.7.1 .J'olitical ldcas of Sri Aurobindo - A Critical Study 6.8 Summary 1 h 'i 6.9 Exercises j i 6.1 INTRODUCTION In 19"' celitury, India camc under the British rule. Due to the spread of moder~ieducation and growing public activities, there developed social awakening in India. The religion of Hindus wns very harshly criticized by the Christian n?issionaries and the British historians but at ~hcsanie timc, researches carried out by the Orientalist scholars revealcd to the world, lhc glorioi~s'tiaadition of the Hindu religion. The Hindus responded to this by initiating reforms in thcir religion and by esfablishing new pub'lie associations to spread their ideas of refor111 and social development anlong the people. -

Gandhi and Mani Bhavan

73 Gandhi and Mani Bhavan Sandhya Mehta Volume 1 : Issue 07, November 2020 1 : Issue 07, November Volume Independent Researcher, Social Media Coordinator of Mani Bhavan, Mumbai, [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 74 Abstract: This narrative attempts to give a brief description of Gandhiji’s association with Mani Bhavan from 1917 to 1934. Mani Bhavan was the nerve centre in the city of Bombay (now Mumbai) for Gandhiji’s activities and movements. It was from here that Gandhiji launched the first nationwide satyagraha of Rowlett Act, started Khilafat and Non-operation movements. Today it stands as a memorial to Gandhiji’s life and teachings. _______ The most distinguished address in a quiet locality of Gamdevi in Mumbai is the historic building, Mani Bhavan - the house where Gandhiji stayed whenever he was in Mumbai from 1917 to 1934. Mani Bhavan belonged to Gandhiji’s friend Revashankar Jhaveri who was a jeweller by profession and elder brother of Dr Pranjivandas Mehta - Gandhiji’s friend from his student days in England. Gandhiji and Revashankarbhai shared the ideology of non-violence, truth and satyagraha and this was the bond of their empathetic friendship. Gandhiji respected Revashankarbhai as his elder brother as a result the latter was ever too happy to Volume 1 : Issue 07, November 2020 1 : Issue 07, November Volume host him at his house. I will be mentioning Mumbai as Bombay in my text as the city was then known. Sambhāṣaṇ Sambhāṣaṇ Volume 1 : Issue 07, November 2020 75 Mani Bhavan was converted into a Gandhi museum in 1955. Dr Rajendra Prasad, then The President of India did the honours of inaugurating the museum. -

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire

Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled By Mukund Ainapure i Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire Volume III Word by word construing in Sanskrit and English of Selected ‘Hymns of the Atris’ from the Rig-veda Compiled by Mukund Ainapure • Original Sanskrit Verses from the Rig Veda cited in The Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo Volume 16, Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Part II – Mandala 5 • Padpātha Sanskrit Verses after resolving euphonic combinations (sandhi) and the compound words (samās) into separate words • Sri Aurobindo’s English Translation matched word-by-word with Padpātha, with Explanatory Notes and Synopsis ii Companion to Hymns to the Mystic Fire – Volume III By Mukund Ainapure © Author All original copyrights acknowledged April 2020 Price: Complimentary for personal use / study Not for commercial distribution iii ॥ी अरिव)दचरणारिव)दौ॥ At the Lotus Feet of Sri Aurobindo iv Prologue Sri Aurobindo Sri Aurobindo was born in Calcutta on 15 August 1872. At the age of seven he was taken to England for education. There he studied at St. Paul's School, London, and at King's College, Cambridge. Returning to India in 1893, he worked for the next thirteen years in the Princely State of Baroda in the service of the Maharaja and as a professor in Baroda College. In 1906, soon after the Partition of Bengal, Sri Aurobindo quit his post in Baroda and went to Calcutta, where he soon became one of the leaders of the Nationalist movement. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

Mother India

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE Vol. LX No. 6 “Great is Truth and it shall prevail” CONTENTS Sri Aurobindo SELF (Poem) ... 421 THE SCIENCE OF CONSCIOUSNESS ... 422 The Mother ‘NO ERROR CAN PERSIST IN FRONT OF THEE’ ... 426 THE POWER OF WORDS ... 427 Amal Kiran (K. D. Sethna) “SAKUNTALA” AND “SAKUNTALA’S FAREWELL”—CORRESPONDENCE WITH SRI AUROBINDO ... 429 Priti Das Gupta MOMENTS, ETERNAL ... 435 Arun Vaidya AN ETERNAL DREAM ... 440 Prabhjot Kulkarni WHO AM I (Poem) ... 447 S. V. Bhatt PAINTING AS SADHANA: KRISHNALAL BHATT (1905-1990) ... 448 Narad (Richard Eggenberger) TEHMI-BEN—NARAD REMEMBERS ... 456 Sitangshu Chakrabortty LORD AND MOTHER NATURE (Poem) ... 464 Bibha Biswas THE BIRTH OF “BATIK WORK” ... 465 Prithwindra Mukherjee BANKIMCHANDRA CHATTERJEE ... 468 Chunilal Chowdhury A WORLD WITHOUT WAR ... 476 Prema Nandakumar DEVOTIONAL POETRY IN TAMIL ... 480 Pujalal NAVANIT STORIES ... 490 421 SELF He said, “I am egoless, spiritual, free,” Then swore because his dinner was not ready. I asked him why. He said, “It is not me, But the belly’s hungry god who gets unsteady.” I asked him why. He said, “It is his play. I am unmoved within, desireless, pure. I care not what may happen day by day.” I questioned him, “Are you so very sure?” He answered, “I can understand your doubt. But to be free is all. It does not matter How you may kick and howl and rage and shout, Making a row over your daily platter. “To be aware of self is liberty. Self I have got and, having self, am free.” SRI AUROBINDO (Collected Poems, SABCL, Vol. -

Foreign Contribution Report

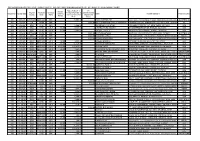

SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM TRUST PONDICHERRY FOREIGN CONTRIBUTION DONORS LIST OCTOBER-20 TO DECEMBER-20(Q3) Rupee Value of ( FC Foreign Original Payment Currency Foreign Chqs/ DDs & Donation(Cash) Receipt No F Receipt Date Currency Name Present Address-1 Present Country Country mode Name Currency Notes )1st (Rupees) 1st Amount Recp. Recpt 300 1-10-20 AUSTRALIA NEFT HDFC INR 5,308.00 RAJIV RATTAN DR GRATITUDE, 159 BOUNDARY ROAD, WAHROONGA, NSW-2076 AUSTRALIA 301 2-10-20 UK CASH INR 1,000.00 SRI AUROBINDO CIRCLE(ASHRAM) 8 SHERWOOD AVE., STREATHAM VALE, SW16 5EW, LONDON UK 302 2-10-20 USA CHQ INR 6,000.00 AURINDAK K GHATAK 455 MAIN STREET # 16F, NEW YORK, NY-10044 USA 303 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 100.00 7,231.00 CHITRALEKHA GHOSH 22 INDEPENDENCE DR, EDISON, NJ-08820 USA 304 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 101.00 7,303.00 SATISH J PATEL 1413 BRYS DR, GROSSE POINTE, MI-48236 USA 305 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,001.00 R VISWANATHAN UNIT-330, 298 SUSSEX ST, NSW-2000, SYDNEY AUSTRALIA 306 2-10-20 USA CASH INR 1,000.00 RICHARD HARTZ C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 307 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,000.00 SUSAN CROTHERS C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 308 2-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 50.00 3,685.25 DINESH MANDAL 1013 ROYAL STOCK LN, CARY, NC-27513 USA 309 2-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 205.00 15,127.46 VIJAYA CHINNADURAI 1739 STIFEL LANE DR, CHESTERFIELD, MO-63017 USA 310 3-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 5,000.00 3,65,425.00 KUSUM PATEL 1694 HIDDEN OAK TRAIL,MANSFIELD, OH-44906 USA 311 3-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 20.00 1,461.70 RAMAKRISHNAN -

(Rjelal) Magic Consciousness and Life Negation of Sri

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Vol.3.3.2015 (July-Sep) Journalhttp://www.rjelal.com RESEARCH ARTICLE MAGIC CONSCIOUSNESS AND LIFE NEGATION OF SRI AUROBINDO’S SELECT POEMS S.KARTHICK1, Dr. O.T. POONGODI2 1(Ph.D) Research Scholar, R & D Cell, Bharathiar Universty, Coimbatore. 2Assistant Professor of English, Thiruvalluvar Govt. Arts College Rasipuram. ABSTRACT Magic consciousness and Life Negation are the divine inclination principle of human being. Spiritual practice made to uplift their eternal journey. It had nothing to do with materialistic worshippers. The dawn of the higher or undivided magic consciousness is only for the super-men who had the right to enter into communion soul with the supra- sensuous. The aim of this paper is to through the light on sacred essence of Sri Aurobindo’s select poems. Under this influences one of the popular imaginations of Atman for the immaterial part of the individual. S.KARTHICK Aurobindo’s poetry asserts that the illuminating hidden meaning of the Vedas. It brings untrammeled inner reflection of the Upanishads. The world of life negation comes from supra- sensuous. It is a truism that often a long writing of the Vedas has come to practice. The Vedas, Upanishads were only handed down orally. In this context seer poets like Sri Aurobindo has intertwined the secret instruction about the hidden meaning of Magic consciousness and Life negation through his poetry. Key words: Supra- Sensuous, Mythopoeic Visionary and Atman. ©KY PUBLICATIONS INTRODUCTION inner truth of Magic consciousness and Life negation “The force varies always according to the cannot always be separated from the three co- power of consciousness which it related aspects of Mystical, Philosophy and Ecstatic. -

Essays in Philosophy and Yoga

13 Essays in Philosophy and Yoga VOLUME 13 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1998 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Essays in Philosophy and Yoga Shorter Works 1910 – 1950 Publisher's Note Essays in Philosophy and Yoga consists of short works in prose written by Sri Aurobindo between 1909 and 1950 and published during his lifetime. All but a few of them are concerned with aspects of spiritual philosophy, yoga, and related subjects. Short writings on the Veda, the Upanishads, Indian culture, politi- cal theory, education, and poetics have been placed in other volumes. The title of the volume has been provided by the editors. It is adapted from the title of a proposed collection, ªEssays in Yogaº, found in two of Sri Aurobindo's notebooks. Since 1971 most of the contents of the volume have appeared under the editorial title The Supramental Manifestation and Other Writings. The contents are arranged in ®ve chronological parts. Part One consists of essays published in the Karmayogin in 1909 and 1910, Part Two of a long essay written around 1912 and pub- lished in 1921, Part Three of essays and other pieces published in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1921, Part Four of an essay published in the Standard Bearer in 1920, and Part Five of a series of essays published in the Bulletin of Physical Education in 1949 and 1950. Many of the essays in Part Three were revised slightly by the author and published in small books between 1920 and 1941. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

A New Creation on Earth: Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mother Mirra Alfassa

A New Creation on Earth: Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mother Mirra Alfassa Stephen Lerner Julich1 Abstract: This paper acts as a précis of the author’s dissertation in East-West Psychology at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. The dissertation, entitled Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mirra Alfassa (1878- 1973), Mother of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram: A Jungian Hermeneutic, is a cross-cultural exploration and analysis of symbols of death and transformation found in Mother’s conversations and writings, undertaken as a Jungian amplification. Focused mainly on her discussions of the psychic being and death, it is argued that the Mother remained rooted in her original Western Occult training, and can best be understood if this training, under the guidance of Western Kabbalist and Hermeticist Max Théon, is seen, not as of merely passing interest, but as integral to her development. Keywords: C.G. Jung, death, integral yoga, Mother Mirra Alfassa, psychic being, Sri Aurobindo, transformation. Mirra Alfassa was one of those rare individuals who was in life a living symbol, at once human, and identical to the indescribable higher reality. Her yoga was to tear down the barrier that separates heaven and earth by defeating the Lord of Death, through breaking the habituated belief that exists in every cell of the body that all life must end in death and dissolution. Ultimately, her goal was to transform and spiritualize matter. In my dissertation I applied a Jungian lens to amplify the Mother’s statements. Amplification, as it is usually understood in Jungian circles, is a method used to expand an analyst’s grasp of images and symbols that appear in the dreams of analysands. -

Topic for Dissertation MA Philosophy Semester

Topic for Dissertation M.A. Philosophy Semester - IV(CBCS) 2017-18 1. The epistemological issues embedded in the skeptical challenge to knowledge as found in Indian tradition. Select Bibliography: Original Sources: Vigrahavyavartani of Nagarjuna Tattopaplvasinha of Jayarashi Bhatta Khandanakhandakhadya of Shriharsha Other sources: ―Lokayata/ Carvaka: A Philosophical Study‖ by Dr. Gokhale Pradip, OUP, 2015 ‗Philosophy, Culture and Religion: Essays by B.K. Matilal‘, Jonardon Ganeri (Ed.) Oxford University Press, Delhi, 2002. 2. The debate between the Realists and the Constructivists in the Context of Indian Epistemology Select Bibliography: Gillon Brebdan S. (Ed.), ‗Logic in Earliest Classical India‘, Motilal Banarasidas, New Delhi, 2010. Bhattacharya H.M. `Jaina Logic and Epistemology‘, K.P. Bagchi &Co., Calcutta, 1994. Popper Karl, `Conjectures and Refutations‘, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1963 Shastri D.N. ―Critique of Indian Realism‖, Bharatiya Vidya Prakashan, 1972. Ayer A.J. `Problem of Knowledge‘, MacMillan, London, 1965. 3. Anekantavada as a paradigm for solving the philosophical issues: A Critical Study Select Bibliography: ‗Aptamimamsa: A Critique of an Authority‘, Editor, Dr. Nagin Shah Pub. Sanskrit- Sanskriti Granthamala, Ahmadabad, 1999. ‗The Central Philosophy of Jainism (Anekantavada)‘, Matilal B.K pub. L.D. Institute of Indology, Ahmadabad, 1981. Tattvartha Sutra,Commen. By Pt. Sukhlalji, Tr.Dixit, K.K. Pub. L.D. Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad, 2000. Harmaless Souls, Johnson, W.J., Motilal Banarasidas Pub. Delhi, 1995. Jaina Path of Purification, Jaini Padmanabh, Motilal Banarasidas, Delhi, 1979 1 Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation, Glasenapp, Helmuth Von, Eng. Trans. Shridhar Shrotri, Motilal Banarasidas Pub. Delhi,1999 Lectures on Jainism, Dr. Tatia, Nathmal , Pub. By Department of Jainology, University of Madras, 1998 4. -

Institute of Human Study Hyderabad

A Journal of Integral and Future Studies Published by Institute of Human Study Hyderabad Volume IVi Issue II Volume IV Issue II NEW RACE is published by Chhalamayi Reddy on behalf of Institute of Human Study, 2-2-4/1, O.U.Road, Hyderabad 500 044. Founder Editor : (Late) Prof. V. Madhusudan Reddy Editor-in-Chief: V. Ananda Reddy Assistant Editor: Shruti Bidwaikar Designing: Vipul Kishore Email: [email protected]; Phone: 040 27098414 On the web: www.instituteofhumanstudy.org ISSN No.: 2454–1176 ii Volume IV Issue II NEW RACE A Journal of Integral & Future Studies August 2018 Volume IV Issue 2 CONTENTS From the Editor's Desk... Section II: Beauty and Delight 36 Shruti Bidwaikar iv Beauty in Women Sri Aurobindo 37 Section I: Truth 1 Laxmiben Patel’s Work Swami Vivekananda: with the Mother “A Soul of Puissance” Deepshikha Reddy 39 Sri Aurobindo 2 The First Flight... (a sketch) “I had some Strange Power” Deepshikha Reddy 42 Swami Vivekananda 4 Towards a Theory of Poetic Creation Sri Aurobindo: Vinod Balakrishnan 43 Bridge between the Section III: Life 47 Past and the Future The Finnish Education Model: M. P. Pandit 7 In the Light of the Mother’s Essays on Education Significance of Sridarshan Koundinya 48 Sri Aurobindo’s Relics Self-Determination and Ananda Reddy 15 the Path Ahead Evolution Next Kisholoy Gupta 53 Alok Pandey 26 Coming in the Clasp of Divine Grace Search for the Unity of Dolan 57 Matter and Energy Sketches of Life Narendra Joshi 31 Oeendrila Guha 59 iii Volume IV Issue II From the Editor's Desk..