Yoga As a Part of Sanātana Dharma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B . Food . Fre E

Website :www.bfoodfree.org Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/NithyanandaNiraharis . OD FR Facebook group : https://www.facebook.com/groups/315287795244130/ O E F . E B BFOODFREE /THE SAMYAMA GUIDE SHEET GETTING OFF TO A GREAT START IN NIRAHARA Nirahara Samyama means to explore and discover your body’s possibilities without having any external input like food or water .Your body is the miniature of the Cosmos, with all possible intelligence in it. If a fish can swim, you can swim, if a bird can fly, you can fly. Food is emotional. When you try to liberate from food and the patterns created by food, first thing will happen to you is – those unnecessary sentiments, emotions associated with food will break. So the reasonless excitement, a kind of subtle joy, will be constantly happening in your system. It is not just an extraordinary power, it is getting into a new Consciousness. When you are free from the patterns of food, such new Consciousness will be awakened. Welcome to the BFoodFree world of NITHYANANDA’S NIRAHARIS J. The following will guide you with THE Samyama: Prerequisites for The Samyama: • The Participant for The samyama (NS level4) must have completed Nirahara Samyama levels 1,2 and 3 officially with integrity and authenticity at least once • Mandatory pre and commitment for post samyama medical reports must be submitted to programs at IA location along with registration( you will not be allowed to do The samyama without medical report) 1. First instruction in THE Samyama is ,you do not control your hunger or thirst by your will power. -

Turiyatita Samyama – Mucus Free Diet -Anger Free Life -30 Days Samyama

TURIYATITA SAMYAMA – MUCUS FREE DIET -ANGER FREE LIFE -30 DAYS SAMYAMA Turiyatita Samyama - From the Words of SPH JGM HDH Bhagawan Sri Nithyananda Paramashivoham *ARUNAGIRI YOGISHWARA HAS GIVEN ME A SACRED SECRET ABOUT THE BIOCHEMISTRY OF TURIYATITA. *RASAVADHA - ALCHEMISTRY SCIENCE MAPPED TO YOUR BODY IS BIOCHEMISTRY SCIENCE; BIOCHEMISTRY OF PARAMASHIVATVA *HE SAID, KABAM UYIR KABADAPPA. KOLAI ARUKKA UYIR KOZHALI AAKKUM. *IT MEANS: THE KAPHA COMPONENT OF THE VATHA, PITTA, KAPHA (3 COMPONENTS IN AYURVEDA) WHICH IS AN ENERGY IF YOU KNOW HOW USE IT, WILL DESTROY THE LIFE ENERGY. *THE WORD KOZHAI MEANS “MUCUS” AND “COWARDNESS” (TWO MEANINGS). THE MUCUS IN YOU WILL MAKE THE CONSCIOUSNESS IN YOU A COWARD. THEN, YOU START THINKING THERE ARE MULTIPLE PEOPLE PLAYING IN YOUR LIFE AND YOU START BLAMING OTHERS WHICH IS A QUALITY OF THE COWARD. *EVEN IF IT IS A FACT AND THEY ARE ATTACKING YOU, TAKING RESPONSIBILITY AND SOLVING THE PROBLEM, IS THE QUALITY OF THE COURAGEOUS BEING. *HE SAID, KOZHAI UYIR KOZHAI AAKKUM… *I WILL TELL YOU WHAT HE SAID AS THE BIOCHEMISTRY OF THE SCIENCE OF WAKING UP TO TURIYATITA. *DO THIS ALCHEMY FOR TWO PAKSHA...EITHER POURNAMI TO AMAVASYA OR AMAVASYA TO POURNAMI IS ONE PAKSHA; SO DO DURING ONE KRISHNA PAKSHA (WANING MOON) AND ONE SHUKLA PAKSHA (GROWING MOON). SO IT WILL BE AROUND 32 DAYS - EITHER POURNAMI TO POURNAMI OR AMAVASYA TO AMAVASYA: AVOID ALL FOOD RELATED TO KAPHA AND MUCUS IN YOUR BODY. HAVE MUCUS-FREE FOOD. *YOUR WILLPOWER EXPERIENCES COWARDNESS IN THREE LEVELS: 1) NOT FEELING POWERFUL TO MANIFEST WHAT YOU WANT 2) NOT THINKING THROUGH OR PLANNING OR ACTING 3) STRONGLY FEELING YOUR OPPOSITE POWERS (PERSONS / SITUATIONS) OTHER THAN YOU ARE EXTREMELY POWERFUL AND HAVING INTENSE FEAR ABOUT IT. -

Vibhuti Pada Patanjali Yoga Sutra

Patanjali Yoga Sutra - Vibhuti Pada Patanjali Yoga Sutra - Vibhuti Pada What is concentration? 3.1 Desabandhaschittasya dharana | Desa-place Bandha-binding Chittasya-of the mind Dharana-concentration Cocentration is binding the mind to one place. Patanjali Yoga Sutra - Vibhuti Pada What is meditation? 3.2. Tatra pratyayaikatanata dhyanam| Tatra-there(in the desha) Pratyaya-basis or content of consciousness Ekatanata-continuity Dhyanam-meditation Uninterrupted stream of the content of consciouness is dhayana. Patanjali Yoga Sutra - Vibhuti Pada What is superconsciousness? 3.3.Tadevarthamatranirbhasaà svarupasunyamiva samadhih| Tadeva-the same Artha-the object of dhayana Matra-only Nirbhasam-appearing Svarüpa-one own form Sunyam-empty Iva-as if Samadhih-trance The state becomes samadhi when there is only the object appearng without the consciousness of ones own self. Patanjali Yoga Sutra - Vibhuti Pada By samyama knowledge of past & future 3.16. Parinamatrayasamymadatitanagatajnanam| Parinama-transformation Traya-three Samymat-by samyama Atita-past Anagatah-future Jnanam-knowledge By performing samyama on the three transformations, knowledge of past and future(arises). Patanjali Yoga Sutra - Vibhuti Pada By samyama knowledge of all speech 3.17. Sabdarthapratyayanamitaretaradhyasat saìkarastat pravibhagasamyamat sarvabhutarutajnanam| Sabda-word Artha-object Pratyayanam-mental content Itaretaradhyasat-because of mental superimposition Sankara-confusion Tat-that Pravibhaga-separate Samyamat-by samyama Sarvabhuta-all living beings Ruta-speech Jnanam-knowledge The word, object and mental content are in a confused state because of mutual superimposition. By performing smyama on them separately, knowledge of the speech of all beings (arises). Patanjali Yoga Sutra - Vibhuti Pada By samyama knowledge of previous birth 3.18. Samskarasaksatkaranat purvajatijnanam| Samskara-impression Saksatkaranat-by direct impression Purva-previous Jati-birth Jnanam-knowledge By direct perception of the impressions, knowledge of previous births(arises). -

Chakra Healing: a Beginner's Guide to Self-Healing Techniques That

I dedicate this book to my grandmother, Lola Anunciacion Pineda Perlas, who always believed in me. Copyright © 2017 by Althea Press, Berkeley, California No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, Althea Press, 918 Parker St., Suite A-12, Berkeley, CA 94710. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: The Publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifically disclaim all warranties, including without limitation warranties of fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales or promotional materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for every situation. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering medical, legal or other professional advice or services. If professional assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Neither the Publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. The fact that an individual, organization or website is referred to in this work as a citation and/or potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the Publisher endorses the information the individual, organization or website may provide or recommendations they/it may make. -

Mother India

MOTHER INDIA MONTHLY REVIEW OF CULTURE Vol. LX No. 6 “Great is Truth and it shall prevail” CONTENTS Sri Aurobindo SELF (Poem) ... 421 THE SCIENCE OF CONSCIOUSNESS ... 422 The Mother ‘NO ERROR CAN PERSIST IN FRONT OF THEE’ ... 426 THE POWER OF WORDS ... 427 Amal Kiran (K. D. Sethna) “SAKUNTALA” AND “SAKUNTALA’S FAREWELL”—CORRESPONDENCE WITH SRI AUROBINDO ... 429 Priti Das Gupta MOMENTS, ETERNAL ... 435 Arun Vaidya AN ETERNAL DREAM ... 440 Prabhjot Kulkarni WHO AM I (Poem) ... 447 S. V. Bhatt PAINTING AS SADHANA: KRISHNALAL BHATT (1905-1990) ... 448 Narad (Richard Eggenberger) TEHMI-BEN—NARAD REMEMBERS ... 456 Sitangshu Chakrabortty LORD AND MOTHER NATURE (Poem) ... 464 Bibha Biswas THE BIRTH OF “BATIK WORK” ... 465 Prithwindra Mukherjee BANKIMCHANDRA CHATTERJEE ... 468 Chunilal Chowdhury A WORLD WITHOUT WAR ... 476 Prema Nandakumar DEVOTIONAL POETRY IN TAMIL ... 480 Pujalal NAVANIT STORIES ... 490 421 SELF He said, “I am egoless, spiritual, free,” Then swore because his dinner was not ready. I asked him why. He said, “It is not me, But the belly’s hungry god who gets unsteady.” I asked him why. He said, “It is his play. I am unmoved within, desireless, pure. I care not what may happen day by day.” I questioned him, “Are you so very sure?” He answered, “I can understand your doubt. But to be free is all. It does not matter How you may kick and howl and rage and shout, Making a row over your daily platter. “To be aware of self is liberty. Self I have got and, having self, am free.” SRI AUROBINDO (Collected Poems, SABCL, Vol. -

Arsha Vidya Newsletter Rs

Arsha Vidya Newsletter Rs. 15/- Vol. 21 January 2020 Issue 1 Valedictory function of 108 days Vedanta course at AVG Anaikati See Report page...26 2 Arsha Vidya Newsletter - January 2020 1 Arsha Vidya Pitham Avinash Narayanprasad Pande Rakesh Sharma,V.B.Somasundaram Swami Dayananda Ashram Madhav Chintaman Kinkhede and Bhagubhai Tailor. Sri Gangadhareswar Trust Ramesh alias Nana Pandurang Swami Dayananda Nagar Gawande Arsha Vidya Gurukulam Rishikesh Pin 249 137, Uttarakhanda Rajendra Wamanrao Korde Ph.0135-2438769 Swamini Brahmaprakasananda Institute of Vedanta and Sanskrit 0135 2430769 Sruti Seva Trust Website: www.dayananda.org Arsha Vidya Gurukulam Anaikatti P.O., Coimbatore 641108 Institute of Vedanta and Sanskrit Email: [email protected] Tel. 0422-2657001 P.O. Box No.1059 Fax 91-0422-2657002 Saylorsburg, PA, 18353, USA Web Site http://www.arshavidya.in Board of Trustees: Tel: 570-992-2339 Email: [email protected] Fax: 570-992-7150 Founder : 570-992-9617 Board of Trustees: Brahmaleena Pujya Sri Web Site : http://www.arshavidhya.org Swami Dayananda BooksDept:http://books.arshavidya.org Founder: Saraswati Brahmaleena Pujya Sri Board of Trustees: Swami Dayananda Saraswati Chairman & Managing Trustee: Founder : Paramount Trustee: Swami Suddhananda Brahmaleena Pujya Sri Saraswati Swami Dayananda Swami Sadatmananda Saraswati Saraswati Swami Shankarananda Saraswati Vice Chairman & Acharya: Swami Sakshatkrutananda Sarasva0 President: Chairman: Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati R. Santharam Trustees: Vice Presidents: Trustees: Swami Tattvavidananda Saras- Sri M.G. Srinivasan wati S. Pathy Sri Rajinikanth Swami Pratyagbodhanada Ravi Sam Sri M. Rajalingam Saraswati R. Kannan Swami Parabrahmananda Ravi Gupta Saraswati Secretary: Sri Madhav Ramachandra Kini, Sri P.R.Venkatrama Raja Swami Jnanananda Saraswati Sri P.R. -

An Introduction to Kundalini Yoga Meditation Techniques That Are Specific for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders

THE JOURNAL OF ALTERNATIVE AND COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE Volume 10, Number 1, 2004, pp. 91–101 ©Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. PRACTICE An Introduction to Kundalini Yoga Meditation Techniques That Are Specific for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders DAVID S. SHANNAHOFF-KHALSA ABSTRACT The ancient system of Kundalini yoga includes a vast array of meditation techniques and many were dis- covered to be specific for treating the psychiatric disorders as we know them today. One such technique was found to be specific for treating obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), the fourth most common psychiatric disorder, and the tenth most disabling disorder worldwide. Two published clinical trials are described here for treating OCD using a specific Kundalini yoga protocol. This OCD protocol also includes techniques that are useful for a wide range of anxiety disorders, as well as a technique specific for learning to manage fear, one for tranquilizing an angry mind, one for meeting mental challenges, and one for turning negative thoughts into positive thoughts. Part of that protocol is included here and published in detail elsewhere. In addition, a num- ber of other disorder-specific meditation techniques are included here to help bring these tools to the attention of the medical and scientific community. These techniques are specific for phobias, addictive and substance abuse disorders, major depressive disorders, dyslexia, grief, insomnia and other sleep disorders. INTRODUCTION been taught that were known by yogis to be specific for dis- tinct psychiatric disorders. These disorders as we know them his paper refers to the system of Kundalini yoga as today have no doubt been common to humanity since the Ttaught by Yogi Bhajan, a living master of Kundalini origin of the species. -

Kundalini Yoga

KUNDALINI YOGA By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION Tenth Edition: 1994 (Copies 10,000) World Wide Web (WWW) Edition: 1999 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7052-052-5 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. OM IN MEMORY OF PATANJALI MAHARSHI, YOGI BHUSUNDA, SADASIVA BRAHMAN, MATSYENDRANATH, GORAKHNATH, JESUS CHRIST, LORD KRISHNA AND ALL OTHER YOGINS WHO HAVE EXPOUNDED THE SCIENCE OF YOGA PUBLISHERS’ NOTE It would seem altogether superfluous to try to introduce Sri Swami Sivananda Saraswati to a reading public, thirsting for spiritual regeneration. From his lovely Ashram at Rishikesh he radiated spiritual knowledge and a peace born of spiritual perfection. His personality has made itself manifest nowhere else as completely as in his edifying and elevating books. And this little volume on Kundalini Yoga is perhaps the most vital of all his books, for obvious reasons. Kundalini is the coiled up, dormant, cosmic power that underlies all organic and inorganic matter within us and any thesis that deals with it can avoid becoming too abstract, only with great difficulty. But within the following pages, the theory that underlies this cosmic power has been analysed to its thinnest filaments, and practical methods have been suggested to awaken this great pristine force in individuals. It explains the theory and illustrates the practice of Kundalini Yoga. -

Foreign Contribution Report

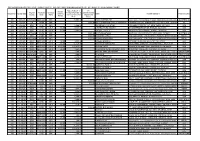

SRI AUROBINDO ASHRAM TRUST PONDICHERRY FOREIGN CONTRIBUTION DONORS LIST OCTOBER-20 TO DECEMBER-20(Q3) Rupee Value of ( FC Foreign Original Payment Currency Foreign Chqs/ DDs & Donation(Cash) Receipt No F Receipt Date Currency Name Present Address-1 Present Country Country mode Name Currency Notes )1st (Rupees) 1st Amount Recp. Recpt 300 1-10-20 AUSTRALIA NEFT HDFC INR 5,308.00 RAJIV RATTAN DR GRATITUDE, 159 BOUNDARY ROAD, WAHROONGA, NSW-2076 AUSTRALIA 301 2-10-20 UK CASH INR 1,000.00 SRI AUROBINDO CIRCLE(ASHRAM) 8 SHERWOOD AVE., STREATHAM VALE, SW16 5EW, LONDON UK 302 2-10-20 USA CHQ INR 6,000.00 AURINDAK K GHATAK 455 MAIN STREET # 16F, NEW YORK, NY-10044 USA 303 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 100.00 7,231.00 CHITRALEKHA GHOSH 22 INDEPENDENCE DR, EDISON, NJ-08820 USA 304 2-10-20 USA CHQ US-$ 101.00 7,303.00 SATISH J PATEL 1413 BRYS DR, GROSSE POINTE, MI-48236 USA 305 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,001.00 R VISWANATHAN UNIT-330, 298 SUSSEX ST, NSW-2000, SYDNEY AUSTRALIA 306 2-10-20 USA CASH INR 1,000.00 RICHARD HARTZ C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 307 2-10-20 AUSTRALIA CASH INR 1,000.00 SUSAN CROTHERS C/O GOLCONDE, 7 RUE DUPUY, PONDICHERRY-605001 INDIA 308 2-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 50.00 3,685.25 DINESH MANDAL 1013 ROYAL STOCK LN, CARY, NC-27513 USA 309 2-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 205.00 15,127.46 VIJAYA CHINNADURAI 1739 STIFEL LANE DR, CHESTERFIELD, MO-63017 USA 310 3-10-20 USA NEFT HDFC US-$ 5,000.00 3,65,425.00 KUSUM PATEL 1694 HIDDEN OAK TRAIL,MANSFIELD, OH-44906 USA 311 3-10-20 INDIA NEFT HDFC US-$ 20.00 1,461.70 RAMAKRISHNAN -

Ishavasya Upanishad

DzÉÉuÉÉxrÉÉåmÉÌlÉwÉiÉç ISHAVASYA UPANISHAD The All-Pervading Reality “THE SANDEEPANY EXPERIENCE” Reflections by TEXT SWAMI GURUBHAKTANANDA 19 Sandeepany’s Vedanta Course List of All the Course Texts in Chronological Sequence: Text TITLE OF TEXT Text TITLE OF TEXT No. No. 1 Sadhana Panchakam 24 Hanuman Chalisa 2 Tattwa Bodha 25 Vakya Vritti 3 Atma Bodha 26 Advaita Makaranda 4 Bhaja Govindam 27 Kaivalya Upanishad 5 Manisha Panchakam 28 Bhagavad Geeta (Discourse -- ) 6 Forgive Me 29 Mundaka Upanishad 7 Upadesha Sara 30 Amritabindu Upanishad 8 Prashna Upanishad 31 Mukunda Mala (Bhakti Text) 9 Dhanyashtakam 32 Tapovan Shatkam 10 Bodha Sara 33 The Mahavakyas, Panchadasi 5 11 Viveka Choodamani 34 Aitareya Upanishad 12 Jnana Sara 35 Narada Bhakti Sutras 13 Drig-Drishya Viveka 36 Taittiriya Upanishad 14 “Tat Twam Asi” – Chand Up 6 37 Jivan Sutrani (Tips for Happy Living) 15 Dhyana Swaroopam 38 Kena Upanishad 16 “Bhoomaiva Sukham” Chand Up 7 39 Aparoksha Anubhuti (Meditation) 17 Manah Shodhanam 40 108 Names of Pujya Gurudev 18 “Nataka Deepa” – Panchadasi 10 41 Mandukya Upanishad 19 Ishavasya Upanishad 42 Dakshinamurty Ashtakam 20 Katha Upanishad 43 Shad Darshanaah 21 “Sara Sangrah” – Yoga Vasishtha 44 Brahma Sootras 22 Vedanta Sara 45 Jivanmuktananda Lahari 23 Mahabharata + Geeta Dhyanam 46 Chinmaya Pledge A NOTE ABOUT SANDEEPANY Sandeepany Sadhanalaya is an institution run by the Chinmaya Mission in Powai, Mumbai, teaching a 2-year Vedanta Course. It has a very balanced daily programme of basic Samskrit, Vedic chanting, Vedanta study, Bhagavatam, Ramacharitmanas, Bhajans, meditation, sports and fitness exercises, team-building outings, games and drama, celebration of all Hindu festivals, weekly Gayatri Havan and Guru Paduka Pooja, and Karma Yoga activities. -

Yoga Terms Decisions; Sometimes Translated As "Intellect." Another Translation Is the Higher Mind, Or Wisdom

buddhi: The determinative faculty of the mind that makes Yoga Terms decisions; sometimes translated as "intellect." Another translation is the higher mind, or wisdom. Source: Omega Institute, http://eomega.com/omega/knowledge/yogaterms/ chakras: nerve centers, or "wheels" of energy, located along the Following are common terms use in the yogic tradition. If a word or spine and considered a part of the subtle body. phrase in a description appears in bold, it can be found under its own heading. cit or chit: lit. "consciousness" or "awareness." Philosophically, pure awareness; transcendent consciousness, as in Sat-chit- abhaya or abhayam: lit. "fearlessness." ananda. In mundane usage, chit means perception; consciousness. agni: lit. "fire." Also the internal fires of the body, often referred to as tapas, meaning sacred heat. When capitalized, the god of fire. darshana: lit. "vision" or sight." Insight or visionary states regarded as a result of meditation. ahamkaara or ahamkara: ego, self-love; selfish individuality. The mental faculty of individuation; sense of duality and separateness daya: compassion to all beings. from others. Ahamkara is characterized by the sense of I-ness (abhimana), sense of mine-ness, identifying with the body dharma: right action, truth in action, righteousness, morality, (madiyam), planning for one's own happiness (mamasukha), virtue, duty, the dictates of God, code of conduct. The inner brooding over sorrow (mamaduhkha), and possessiveness (mama constitution of a thing that governs its growth. idam). drishti: lit. "pure seeing." ahimsa: lit. "noninjury." Nonviolence or nonhurtfulness. Refraining from causing harm to others, physically, mentally or emotionally. eight limbs of yoga or the eightfold path: in Sanskrit, this is Ahimsa is the first and most important of the yamas (restraints). -

Essays in Philosophy and Yoga

13 Essays in Philosophy and Yoga VOLUME 13 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1998 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Essays in Philosophy and Yoga Shorter Works 1910 – 1950 Publisher's Note Essays in Philosophy and Yoga consists of short works in prose written by Sri Aurobindo between 1909 and 1950 and published during his lifetime. All but a few of them are concerned with aspects of spiritual philosophy, yoga, and related subjects. Short writings on the Veda, the Upanishads, Indian culture, politi- cal theory, education, and poetics have been placed in other volumes. The title of the volume has been provided by the editors. It is adapted from the title of a proposed collection, ªEssays in Yogaº, found in two of Sri Aurobindo's notebooks. Since 1971 most of the contents of the volume have appeared under the editorial title The Supramental Manifestation and Other Writings. The contents are arranged in ®ve chronological parts. Part One consists of essays published in the Karmayogin in 1909 and 1910, Part Two of a long essay written around 1912 and pub- lished in 1921, Part Three of essays and other pieces published in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1921, Part Four of an essay published in the Standard Bearer in 1920, and Part Five of a series of essays published in the Bulletin of Physical Education in 1949 and 1950. Many of the essays in Part Three were revised slightly by the author and published in small books between 1920 and 1941.