Contents Sept 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF ( 444KB )

Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 73(1): 215–220. 2021 215 doi: 10.26492/gbs73(1).2021-11 Clarification of the taxonomic identity, typification and nomenclature of Impatiens benthamii (Balsaminaceae) R. Gogoi1*, B.B.T. Tham2, N. Sherpa1, J. Dihingia3 & S. Borah4 1Botanical Survey of India, Sikkim Himalayan Regional Centre, P.O. Rajbhawan, Gangtok–737103, Sikkim, India *[email protected] 2Botanical Survey of India, Eastern Regional Centre, Shillong – 793003, Meghalaya, India 3Dakshin Kamrup Bidyapith High School, Mirza – 781125, Assam, India 4Department of Botany, Gauhati University, Guwahati – 781014, Assam, India ABSTRACT. Impatiens benthamii Steenis (Balsaminaceae) is re-collected from the type locality, Khasi Hills, Meghalaya, India, almost 60 years since it was last collected. The history and nomenclatural complexity of this little-known endemic species is discussed. A clarification of the distributional range of the species is given due to previous erroneous reports. To facilitate its proper identification, a detailed description based on live materials and colour photographs is provided. The characters of Impatiens benthamii are compared to those of closely related species. A lectotype is designated. Keywords. Distribution, endemic, Khasi Hills, lectotype Introduction The Indian species Impatiens radicans Benth. ex Hook.f & Thomson first appeared in Wallich (1832) but this name was not validly published. It was later validly published in Hooker & Thomson (1859). In the same publication they also published Impatiens salicifolia Hook.f. & Thomson which was later synonymised with I. radicans (Hooker, 1905). However, the name Impatiens radicans Benth. ex Hook.f. & Thomson is a later homonym of I. radicans Zoll. & Moritzi (Moritzi, 1846). Impatiens radicans Zoll. & Moritzi is now treated as a synonym of I. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

A New Creation on Earth: Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mother Mirra Alfassa

A New Creation on Earth: Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mother Mirra Alfassa Stephen Lerner Julich1 Abstract: This paper acts as a précis of the author’s dissertation in East-West Psychology at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. The dissertation, entitled Death and Transformation in the Yoga of Mirra Alfassa (1878- 1973), Mother of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram: A Jungian Hermeneutic, is a cross-cultural exploration and analysis of symbols of death and transformation found in Mother’s conversations and writings, undertaken as a Jungian amplification. Focused mainly on her discussions of the psychic being and death, it is argued that the Mother remained rooted in her original Western Occult training, and can best be understood if this training, under the guidance of Western Kabbalist and Hermeticist Max Théon, is seen, not as of merely passing interest, but as integral to her development. Keywords: C.G. Jung, death, integral yoga, Mother Mirra Alfassa, psychic being, Sri Aurobindo, transformation. Mirra Alfassa was one of those rare individuals who was in life a living symbol, at once human, and identical to the indescribable higher reality. Her yoga was to tear down the barrier that separates heaven and earth by defeating the Lord of Death, through breaking the habituated belief that exists in every cell of the body that all life must end in death and dissolution. Ultimately, her goal was to transform and spiritualize matter. In my dissertation I applied a Jungian lens to amplify the Mother’s statements. Amplification, as it is usually understood in Jungian circles, is a method used to expand an analyst’s grasp of images and symbols that appear in the dreams of analysands. -

NO PLACE for CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO PLACE FOR CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Information and Communication Act ......................................................................................... 3 Punishing Government Critics ...................................................................................................4 Protecting Religious -

July 2017 Special Issue Introduction

July 2017 Special Issue Volume 13, No 1 Integral Education, Women’s Spirituality and Integral Feminist Pedagogies Table of Contents Special Issue Introduction ......................................................................... 1 Bahman Shirazi The Modern Knowledge Academy, Vedantic Education and Integral Education ................................................................................................... 5 Debashish Banerji A Complete Integral Education: Five Principal Aspects ........................ 20 Jeremie Zulaski The Value of an Integral Education: A Mixed-Method Study with Alumni of the East-West Psychology Program at the California Institute of Integral Studies ................................................................................... 30 Heidi Fraser Hageman Women’s Spirituality at CIIS: Uniting Integral and Feminist Pedagogies ................................................................................................................. 62 Alka Arora cont'd next page The Divine Feminist: A Diversity of Perspectives That Honor Our Mothers’ Gardens by Integrating Spirituality and Social Justice ........... 72 Arisika Razak The Borderlands Feminine: A Feminist, Decolonial Framework for Re- membering Motherlines in South Asia/Transnational Culture ............... 87 Monica Mody Chinmoyee and Mrinmoyee .................................................................... 99 Karabi Sen July 2017 Special Issue Introduction Issue Editor: Bahman A. K. Shirazi1 The focus of this special issue of Integral Review -

Sri Aurobindo's Formulations of the Integral Yoga Debashish Banerji California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, USA

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 37 | Issue 1 Article 6 9-1-2018 Sri Aurobindo's Formulations of the Integral Yoga Debashish Banerji California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA, USA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Banerji, D. (2018). Sri Aurobindo's formulations of the integral yoga. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 37 (1). http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2018.37.1.38 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sri Aurobindo's Formulations of the Integral Yoga Debashish Banerji California Institute of Integral Studies San Francisco, CA, USA Sri Aurobindo Ghose (1872–1950) developed, practiced and taught a form of yoga, which he named integral yoga. If one peruses the texts he has written pertaining to his teaching, one finds a variety of models, goals, and practices which may be termed formulations or versions of the integral yoga. This article compares three such formulations, aiming to determine whether these are the same, but in different words, as meant for different audiences, or whether they represent different understandings of the yoga based on changing perceptions. -

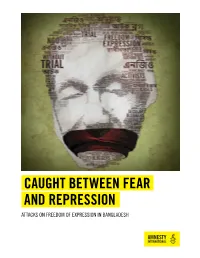

Caught Between Fear and Repression

CAUGHT BETWEEN FEAR AND REPRESSION ATTACKS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN BANGLADESH Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover design and illustration: © Colin Foo Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 13/6114/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION TIMELINE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & METHODOLOGY 6 1. ACTIVISTS LIVING IN FEAR WITHOUT PROTECTION 13 2. A MEDIA UNDER SIEGE 27 3. BANGLADESH’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW 42 4. BANGLADESH’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK 44 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 57 Glossary AQIS - al-Qa’ida in the Indian Subcontinent -

Grandi Personalità Spirituali D'oriente E D'occidente

Luigi Maria Sanguineti Grandi personalità spirituali d’Oriente e d’Occidente. Sri Aurobindo , Gandhi , Gurdijeff , Ignazio di Loyola , Prabhupada, Sri Ramakrishna, Sri Ramana Maharishi, Steiner, Calvino, Lutero, Pascal. Con gli auspici de “La Enciclopedia del pratico e del praticante” ( www.praticadiritto.it ) e di “Professionisti creativi” Sommario AVVERTENZE………………………………………………………………… SRI AUROBINDO ............................................................................................................................ 5 GANDHI ........................................................................................................................................... 10 GANDHI: BIOGRAFIA ........................................................................................ 10 GANDHI: OROSCOPO ........................................................................................ 19 GANDHI : ANALISI GRAFOLOGICA DEL MORETTI. ............................... 21 GURDJIEFF ..................................................................................................................................... 22 BIOGRAFIA ........................................................................................................... 22 GURDJIEFF : OROSCOPO ................................................................................ 32 IGNAZIO DI LOYOLA .................................................................................................................. 33 PRABHUPADA ............................................................................................................................... -

A Spiritual Journey to the East Experimentation in Alternative Living Among Western Travelers in a Spiritual Community in India

A Spiritual Journey to the East Experimentation in Alternative Living Among Western Travelers in a Spiritual Community in India Camilla Gjerde Department of Social Anthropology NTNU Spring, 2013 1 A Spiritual Journey to the East Experimentation in Alternative Living Among Western Travelers in a Spiritual Community in India Camilla Gjerde Department of Social Anthropology NTNU Spring, 2013 2 Abstract What makes people from the West pursue happiness and inner self-fulfillment in a spiritual community in India? What triggers people to embark on a spiritual quest, and more importantly, what do they find? This thesis is based on my field trip carried out in a spiritual, intentional and international community called Auroville that is based in Tamil Nadu, south in India. Auroville’s philosophy is founded on the Indian philosopher Sri Aurobindo (1872- 1959) who assert that man should work towards realizing one’s inner real potentials. Auroville became the place this practice should be realized, and were constructed by Mira Alfassa (1878-1973), Sri Aurobindo’s closest collaborator. Auroville became an experimental city and is dominated by this spiritual discourse that requires its citizens to seek and realize one’s inner self, which is associated with one’s origin and authenticity. I assert that the thought about authentic living and an authentic self found a great resonance amongst my informants, and created a change in their notions about the world. This I argue to be a result of the individual’s ability and will to change – which correspond with the self’s reflexive project in modern contemporary society. There is a need to become who one truly is (Bauman 2000; Giddens 1991; Helaas 2005). -

Aurobindo's Idea on Spiritual Education

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 11, November 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Aurobindo’s ideA on spirituAl educAtion Arnab Kumar Roy* Abstract The future of mankind depends on the education.It is also said that the development of a nation is influenced by education.Education is of various types-physical,mental,psychic,spiritual etc.The general aim of all types of education is to make the man worthy of living. The specific aim of spiritual education is to help a person to realise the divine consciousness and become a perfect instrument of its manifestation. Now- a-days spiritual education has become the most neglected aspect of life.But it is so much necessary at present for mental improvement of human beings that the valuable thoughts of the visionaries and educationalists regarding this type of education need to be followed at any cost to protect the human civilization from going astray. Aurobindo Ghosh,the great philosopher and educationalist laid emphasis on spiritual education as the most important mean of education observing the drawback in the education system not only of India but also of the other countries of the world. In the present paper an effort has been given to examine critically Aurobindo’s spiritual education,its aim and relevance in today’s context. -

On September 23 2010, HM King Abdullah II of Jordan Introduced A

Resolution UNGA A/65/PV.34 On September 23rd 2010, HM King Abdullah II of Jordan introduced a World Interfaith Harmony Week at the Plenary Session of the 65th UN General Assembly in New York. For this unprecedented global harmony initiative HM King Abdullah II of Jordan was recognized in the Global Harmony Association (GHA) as WORLD HARMONY CREATOR www.peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=513 Spiritual Culture for Harmonious Civilization Citizens of Earth! Unite in harmony for love, peace, justice, fraternity and happiness! Global Harmony Association (GHA) Since 2005, GHA is an international NGO uniting more than 500 members in 56 countries and more than one million participants from the GHA collective members in 80 countries. Web: www.peacefromharmony.org Board: 37 GHA members from 14 countries www.peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=249 GHA Founder and President: Dr. Leo Semashko Address: 7/4-42 Ho-Shi-Min Street, St. Petersburg, 194356 Russia E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.peacefromharmony.org/?cat=en_c&key=253 GHA Mission is: To bring peace from harmony and to pave a conscious way for harmonious civilization on scientifically based ‘ABC of Harmony’ through harmonious education 1 World Interfaith Harmony: Internal Harmonious Potential of Religions and General Scientific Platform of the ABC of Harmony Interfaith Harmony Educational Project of the GHA Project Meaning The UN World Interfaith Harmony Week is the second great intuitive step of humanity to global harmony and harmonious civilization after the Congress of World Religions in 1893, Chicago. The highest purpose and subject of the GHA Project of World Interfaith Harmony is to make this step from the intuitive into scientific-conscious o-ne and commit it o-n the fundamentally new way of global harmonious education at the ABC of Harmony base. -

Encyclopedia of Hinduism J: AF

Encyclopedia of Hinduism J: AF i-xL-hindu-fm.indd i 12/14/06 1:02:34 AM Encyclopedia of Buddhism Encyclopedia of Catholicism Encyclopedia of Hinduism Encyclopedia of Islam Encyclopedia of Judaism Encyclopedia of Protestantism i-xL-hindu-fm.indd ii 12/14/06 1:02:34 AM Encyclopedia of World Religions nnnnnnnnnnn Encyclopedia of Hinduism J: AF Constance A. Jones and James D. Ryan J. Gordon Melton, Series Editor i-xL-hindu-fm.indd iii 12/14/06 1:02:35 AM Encyclopedia of Hinduism Copyright © 2007 by Constance A. Jones and James D. Ryan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the pub- lisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 ISBN-10: 0-8160-5458-4 ISBN-13: 978-0-8160-5458-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Constance A., 1961– Encyclopedia of Hinduism / Constance A. Jones and James D. Ryan. p. cm. — (Encyclopedia of world religions) Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9 1. Hinduism—Encyclopedias. I. Ryan, James D. II. Title. III. Series. BL1105.J56 2006 294.503—dc22 2006044419 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755.