Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with At-Risk Families

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Kinship Terminology

Fox (Mesquakie) Kinship Terminology IVES GODDARD Smithsonian Institution A. Basic Terms (Conventional List) The Fox kinship system has drawn a fair amount of attention in the ethno graphic literature (Tax 1937; Michelson 1932, 1938; Callender 1962, 1978; Lounsbury 1964). The terminology that has been discussed consists of the basic terms listed in §A, with a few minor inconsistencies and errors in some cases. Basically these are the terms given by Callender (1962:113-121), who credits the terminology given by Tax (1937:247-254) as phonemicized by CF. Hockett. Callender's terms include, however, silent corrections of Tax from Michelson (1938) or fieldwork, or both. (The abbreviations are those used in Table l.)1 Consanguines Grandparents' Generation (1) nemesoha 'my grandfather' (GrFa) (2) no hkomesa 'my grandmother' (GrMo) Parents' Generation (3) nosa 'my father' (Fa) (4) nekya 'my mother' (Mo [if Ego's female parent]) (5) nesekwisa 'my father's sister' (Pat-Aunt) (6) nes'iseha 'my mother's brother' (Mat-Unc) (7) nekiha 'my mother's sister' (Mo [if not Ego's female parent]) 'Other abbreviations used are: AI = animate intransitive; AI + O = tran- sitivized AI; Ch = child; ex. = example; incl. = inclusive; m = male; obv. = obviative; pi. = plural; prox. = proximate; sg. = singular; TA = transitive ani mate; TI-0 = objectless transitive inanimate; voc. = vocative; w = female; Wi = wife. Some citations from unpublished editions of texts by Alfred Kiyana use abbreviations: B = Buffalo; O = Owl (for these, see Goddard 1990a:340). 244 FOX -

Children and Stepfamilies: a Snapshot

Children and Stepfamilies: A Snapshot by Chandler Arnold November, 1998 A Substantial Percentage of Children live in Stepfamilies. · More than half the Americans alive today have been, are now, or eventually will be in one or more stepfamily situations during their lives. One third of all children alive today are expected to become stepchildren before they reach the age of 18. One out of every three Americans is currently a stepparent, stepchild, or stepsibling or some other member of a stepfamily. · Between 1980 and 1990 the number of stepfamilies increased 36%, to 5.3 million. · By the year 2000 more Americans will be living in stepfamilies than in nuclear families. · African-American children are most likely to live in stepfamilies. 32.3% of black children under 18 residing in married-couple families do so with a stepparent, compared with 16.1% of Hispanic origin children and 14.6% of white children. Stepfamily Situations in America Of the custodial parents who have chosen to remarry we know the following: · 86% of stepfamilies are composed of biological mother and stepfather. · The dramatic upsurge of people living in stepfamilies is largely do to America’s increasing divorce rate, which has grown by 70%. As two-thirds of the divorced and widowed choose to remarry the number of stepfamilies is growing proportionately. The other major factor influencing the number of people living in stepfamilies is the fact that a substantial number of children entering stepfamilies are born out of wedlock. A third of children entering stepfamilies do so after birth to an unmarried mother, a situation that is four times more common in black stepfamilies than white stepfamilies.1 Finally, the mode of entry into stepfamilies also varies drastically with the age of children: while a majority of preschoolers entering stepfamilies do so after nonmarital birth, the least frequent mode of entry for these young children (16%) fits the traditional conception of a stepfamily as formed 1 This calculation includes children born to cohabiting (but unmarried) parents. -

When Parents Disagree on How to Discipline

When Parents Disagree on How to Discipline by Karen Stephens Families can weather occasional parenting differences. But when discipline styles are vastly different, children suffer as does the parent partnership. Discipline disagreements that regularly spin out of control threaten children’s sense of trust, security, and stability. Children know when their behavior is the center of conflict, so they suffer guilt, too. When the outcome of a discipline decision will have small impact on family harmony and children’s well-being, parents often take turns bowing to each other’s preference. One parent often defers to the other’s wishes based on past experi- ences or perceived expertise. For instance, a parent who played an instrument as a child may be granted final say on how to discipline a child who avoids practicing. For overall family harmony, it’s wise to plan ahead on ways parents can cope with differing discipline beliefs. Dr. Connor Walters, certified Family Life Educator at Early in Illinois State University, recommends the following as first steps. Before You Face a Discipline Disagreement • Early in childrearing (if not before!), parents should talk about child discipline childrearing, beliefs and their goals for discipline. Following are questions to discuss: What values do you want to encourage in children? Do you want children to learn self-control and become self-directed? Is your goal for children to become sensitive to the feelings and needs of others? Do you hope children will learn parents to take responsibility and accept the consequences of their behavior? • Next, analyze how your child-rearing methods support or work against the goals you discussed. -

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean Prepared by: Dr. Godfrey St. Bernard The University of the West Indies St. Augustine Trinidad and Tobago Phone Contacts: 1-868-776-4768 (mobile) 1-868-640-5584 (home) 1-868-662-2002 ext. 2148 (office) E-mail Contacts: [email protected] [email protected] Prepared for: United Nations Division of Social Policy and Development Department of Economic and Social Affairs Program on the Family Date: May 23, 2003 Introduction Though an elusive concept, the family is a social institution that binds two or more individuals into a primary group to the extent that the members of the group are related to one another on the basis of blood relationships, affinity or some other symbolic network of association. It is an essential pillar upon which all societies are built and with such a character, has transcended time and space. Often times, it has been mooted that the most constant thing in life is change, a phenomenon that is characteristic of the family irrespective of space and time. The dynamic character of family structures, - including members’ status, their associated roles, functions and interpersonal relationships, - has an important impact on a host of other social institutional spheres, prospective economic fortunes, political decision-making and sustainable futures. Assuming that the ultimate goal of all societies is to enhance quality of life, the family constitutes a worthy unit of inquiry. Whether from a social or economic standpoint, the family is critical in stimulating the well being of a people. The family has been and will continue to be subjected to myriad social, economic, cultural, political and environmental forces that shape it. -

What Is a Child & Family Team Meeting?

What is a Child & Family Team When is a Child & Family Team Meeting Location and Time Meeting? Meeting Necessary? We believe that Child & Family Team Meetings should be conducted at a mutu- A Child & Family Team Meeting (CFT) is A child has been found to be at high risk. ally agreeable and accessible location/time a strength based meeting that brings to- A child is at risk of out of home place- that maximizes opportunities for family gether your family, natural supports, and ment. participation. Please let us know your pref- formal resources. The meeting is lead by a Prior to the removal of a child from his erences regarding the time and location of trained facilitator to ensure that all partici- home. your meeting. pants have an opportunity to be involved Prior to a placement change of a child and heard. The purpose of the meeting is already in care. You have the right to…. to address the needs of your family and to Have your rights explained to you in a Prior to a change in a child’s perma- manner which is clear build upon its strengths. The goal of the nency goal. process is to enable your child(ren) to re- When requested by a parent, social main safely at home whenever possible. Receive written information or interpre- worker, or youth. tation in your native language. When there are multiple agencies in- The purpose of the Child & volved. Read, review, and receive written infor- At other critical decision points. mation regarding your child’s record Family Team Meeting is upon request. -

Punishment on Trial √ Feel Guilty When You Punish Your Child for Some Misbehavior, but Have Ennio Been Told That Such Is Bad Parenting?

PunishmentPunishment onon TrialTrial Cipani PunishmentPunishment onon TrialTrial Do you: √ believe that extreme child misbehaviors necessitate physical punishment? √ equate spanking with punishment? √ believe punishment does not work for your child? √ hear from professionals that punishing children for misbehavior is abusive and doesn’t even work? Punishment on Trial Punishment on √ feel guilty when you punish your child for some misbehavior, but have Ennio been told that such is bad parenting? If you answered “yes” to one or more of the above questions, this book may Cipani be just the definitive resource you need. Punishment is a controversial topic that parents face daily: To use or not to use? Professionals, parents, and teachers need answers that are based on factual information. This book, Punishment on Trial, provides that source. Effective punishment can take many forms, most of which do not involve physical punishment. This book brings a blend of science, clinical experience, and logic to a discussion of the efficacy of punishment for child behavior problems. Dr. Cipani is a licensed psychologist with over 25 years of experience working with children and adults. He is the author of numerous books on child behavior, and is a full professor in clinical psychology at Alliant International University in Fresno, California. 52495 Context Press $24.95 9 781878 978516 1-878978-51-9 A Resource Guide to Child Discipline i Punishment on Trial ii iii Punishment on Trial Ennio Cipani Alliant International University CONTEXT PRESS Reno, Nevada iv ________________________________________________________________________ Punishment on Trial Paperback pp. 137 Distributed by New Harbinger Publications, Inc. ________________________________________________________________________ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cipani, Ennio. -

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Convention on the Rights of the Child Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with article 49 Preamble The States Parties to the present Convention, Considering that, in accordance with the principles proclaimed in the Charter of the United Nations, recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Bearing in mind that the peoples of the United Nations have, in the Charter, reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights and in the dignity and worth of the human person, and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Recognizing that the United Nations has, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the International Covenants on Human Rights, proclaimed and agreed that everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth therein, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, Recalling that, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations has proclaimed that childhood is entitled to special care and assistance, Convinced that the family, as the fundamental group of society and the natural environment for the growth and well-being of all its members and particularly children, should be afforded -

Investigations of Homeschooling Families: by Dewitt T

Child Protective Services Investigations of Homeschooling Families: by Dewitt T. Black, III Are You Next? Senior Counsel Whereas HSLDA records indicate a 25% increase in the According to data collected by the U.S. investigation of our member families during the two-year Department of Health and Human Services period between 2009 and 2011, reports to CPS for the gen- (HHS), a total of 2.8 million referrals concern- eral population increased by only 17% during the ten-year ing approximately 5 million children were period between 2000 and 2010. What is obvious is that CPS made to child protective services (CPS) agen- investigations of homeschooling families are increasing at a rate much higher than for the general population. cies in 2000. Of the investigations conducted, only 28% were substantiated as child abuse The fact that the vast majority of hotline reports to CPS are or neglect. The remaining 72% were placed later deemed unwarranted is little comfort to the nearly 2 in categories not warranting any legal action million families who each year experience the trauma of being against the alleged perpetrators. investigated by social workers for allegedly abusing or neglect- ing their children. A parent’s worst fear is that her children Ten years later in 2010, the most recent year with available will be taken away by a social worker and placed in a stranger’s data, CPS received an estimated 3.3 million referrals involv- home, and social workers readily use this threat to coerce ing the alleged maltreatment of approximately 5.9 million families into cooperating with an investigation. -

Is Corporal Punishment Child Abuse?

St. Catherine University SOPHIA Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers School of Social Work 5-2017 Crossing the Line: Is Corporal Punishment Child Abuse? Jade R. Wallat St. Catherine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Wallat, Jade R.. (2017). Crossing the Line: Is Corporal Punishment Child Abuse?. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/806 This Clinical research paper is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Social Work at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CROSSING THE LINE: IS CORPORAL PUNISHMENT CHILD ABUSE? Crossing the Line: Is Corporal Punishment Child Abuse? Submitted by Jade R. Wallat May 2017 MSW Clinical Research Paper School of Social Work St. Catherine University & University of St. Thomas St. Paul, Minnesota Committee Members: Dr. Lance Peterson (Chair) Jaime Robertson MSW, LSW The Clinical Research Project is a graduation requirement for MSW students at St. Catherine University/University of St. Thomas School of Social Work in St. Paul, Minnesota and is conducted within a nine-month time frame to demonstrate facility with basic social research methods. Students must independently conceptualize a research problem, formulate a research design that is approved by a research committee and the university Institutional Review Board, implement the project, and publicly present the findings of the study. This project is neither a Master’s thesis nor a dissertation. -

A Six Week Parenting Program for Child Compliance

JEIBI Volume 2, Issue No. 1, Winter, 2005 A Six Week Parenting Program For Child Compliance Ennio Cipani, Ph.D. Cipani & Associates Child compliance is an important skill for young children to develop. It is often the focus of intervention efforts. This paper presents a six week program for professionals to use in parent training. At each week, new parenting skills are taught and utilized in real life child compliance situations. Data collection is built into the six-week program. For assistance to professionals and parents, the article presents the manual in its entirety for use. Keywords: Parent training, manual, child compliance, six week program, behavioral procedures. Compliance problems in young children are often at the heart of many parent-child difficulties. It is an area where effective treatments are available (Van Hasselt, Sisson, & Aach, 1987). Parent training procedures based on a behavioral approach incorporating antecedent and consequent components provide an empirical evidence-base for users (Cipani, 2004; Issac, 1982; O’Dell, 1974). This parent-training manual lays out a step-by-step plan for developing key skills in parents for compliance situations. Professionals can use the manual in individual parent training efforts as well as group training formats that span a six-week (or longer period). If used individually, it can be tailored to fit the individual client needs and may require more or less time than six weeks. It is recommended that the skills taught should be kept in their current sequence. A child’s compliance to simple parental commands is an important skill to develop. Isn’t life more harmonious when children put their back packs up without constant reminding? What about living with children who fail to respond to your requests, time and time again? Is a child’s failure to comply a satisfying state of affairs? Which family would you like to be “parent for a week”: Ozzie & Harriet Nelson or the Simpson’s? While you may laugh more at Bart, you certainly hope he is your neighbor’s child, and not yours. -

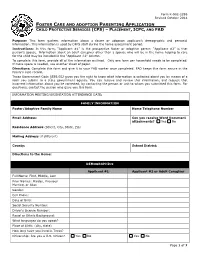

Foster Care and Adoption Parenting Application PDF Document

Form K-902-2286 Revised October 2014 FOSTER CARE AND ADOPTION PARENTING APPLICATION CHILD PROTECTIVE SERVICES (CPS) – PLACEMENT, ICPC, AND FAD Purpose: This form gathers information about a foster or adoption applicant’s demographic and personal information. This information is used by DFPS staff during the home assessment period. Instructions: In this form, “Applicant #1” is the prospective foster or adoptive parent. “Applicant #2” is that person’s spouse. Information about an adult caregiver other than a spouse who will be in the home helping to care for the child may be included in the “Applicant #2” column. To complete this form, provide all of the information outlined. Only one form per household needs to be completed. If more space is needed, use another sheet of paper. Directions: Complete this form and give it to your FAD worker once completed. FAD keeps this form secure in the family’s case record. Texas Government Code §559.002 gives you the right to know what information is collected about you by means of a form you submit to a state government agency. You can receive and review this information, and request that incorrect information about you be corrected, by contacting the person or unit to whom you submitted this form. For questions, contact the person who gave you this form. INFORMATION MEETING/ORIENTATION ATTENDANCE DATE: FAMILY INFORMATION Foster/Adoptive Family Name Home Telephone Number Email Address: Can you receive Word Document attachments? Yes No Residence Address (Street, City, State, Zip) Mailing Address (if different) County: School District: Directions to the Home: DEMOGRAPHICS Applicant #1 Applicant #2 or Adult Caregiver Full Name: First, Middle, Last Prior Names: Maiden, Previous Married, or Alias Gender: Cell Phone: Date of Birth: Social Security Number: Driver's License Number: Racial or Ethnic Background: What languages do you speak? Place of Birth: (city, state) How long have you lived in Texas? Citizenship: Are you a U.S.