Formal Analysis of Kinship Terminologies and Its Relationship to What Constitutes Kinship (Complete Text)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Kinship Terminology

Fox (Mesquakie) Kinship Terminology IVES GODDARD Smithsonian Institution A. Basic Terms (Conventional List) The Fox kinship system has drawn a fair amount of attention in the ethno graphic literature (Tax 1937; Michelson 1932, 1938; Callender 1962, 1978; Lounsbury 1964). The terminology that has been discussed consists of the basic terms listed in §A, with a few minor inconsistencies and errors in some cases. Basically these are the terms given by Callender (1962:113-121), who credits the terminology given by Tax (1937:247-254) as phonemicized by CF. Hockett. Callender's terms include, however, silent corrections of Tax from Michelson (1938) or fieldwork, or both. (The abbreviations are those used in Table l.)1 Consanguines Grandparents' Generation (1) nemesoha 'my grandfather' (GrFa) (2) no hkomesa 'my grandmother' (GrMo) Parents' Generation (3) nosa 'my father' (Fa) (4) nekya 'my mother' (Mo [if Ego's female parent]) (5) nesekwisa 'my father's sister' (Pat-Aunt) (6) nes'iseha 'my mother's brother' (Mat-Unc) (7) nekiha 'my mother's sister' (Mo [if not Ego's female parent]) 'Other abbreviations used are: AI = animate intransitive; AI + O = tran- sitivized AI; Ch = child; ex. = example; incl. = inclusive; m = male; obv. = obviative; pi. = plural; prox. = proximate; sg. = singular; TA = transitive ani mate; TI-0 = objectless transitive inanimate; voc. = vocative; w = female; Wi = wife. Some citations from unpublished editions of texts by Alfred Kiyana use abbreviations: B = Buffalo; O = Owl (for these, see Goddard 1990a:340). 244 FOX -

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with At-Risk Families

ISSUE BRIEF January 2013 Parent-Child Interaction Therapy With At-Risk Families Parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT) is a family-centered What’s Inside: treatment approach proven effective for abused and at-risk children ages 2 to 8 and their caregivers—birth parents, • What makes PCIT unique? adoptive parents, or foster or kin caregivers. During PCIT, • Key components therapists coach parents while they interact with their • Effectiveness of PCIT children, teaching caregivers strategies that will promote • Implementation in a child positive behaviors in children who have disruptive or welfare setting externalizing behavior problems. Research has shown that, as a result of PCIT, parents learn more effective parenting • Resources for further information techniques, the behavior problems of children decrease, and the quality of the parent-child relationship improves. Child Welfare Information Gateway Children’s Bureau/ACYF 1250 Maryland Avenue, SW Eighth Floor Washington, DC 20024 800.394.3366 Email: [email protected] Use your smartphone to https:\\www.childwelfare.gov access this issue brief online. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy With At-Risk Families https://www.childwelfare.gov This issue brief is intended to build a better of the model, which have been experienced understanding of the characteristics and by families along the child welfare continuum, benefits of PCIT. It was written primarily to such as at-risk families and those with help child welfare caseworkers and other confirmed reports of maltreatment or neglect, professionals who work with at-risk families are described below. make more informed decisions about when to refer parents and caregivers, along with their children, to PCIT programs. -

Children and Stepfamilies: a Snapshot

Children and Stepfamilies: A Snapshot by Chandler Arnold November, 1998 A Substantial Percentage of Children live in Stepfamilies. · More than half the Americans alive today have been, are now, or eventually will be in one or more stepfamily situations during their lives. One third of all children alive today are expected to become stepchildren before they reach the age of 18. One out of every three Americans is currently a stepparent, stepchild, or stepsibling or some other member of a stepfamily. · Between 1980 and 1990 the number of stepfamilies increased 36%, to 5.3 million. · By the year 2000 more Americans will be living in stepfamilies than in nuclear families. · African-American children are most likely to live in stepfamilies. 32.3% of black children under 18 residing in married-couple families do so with a stepparent, compared with 16.1% of Hispanic origin children and 14.6% of white children. Stepfamily Situations in America Of the custodial parents who have chosen to remarry we know the following: · 86% of stepfamilies are composed of biological mother and stepfather. · The dramatic upsurge of people living in stepfamilies is largely do to America’s increasing divorce rate, which has grown by 70%. As two-thirds of the divorced and widowed choose to remarry the number of stepfamilies is growing proportionately. The other major factor influencing the number of people living in stepfamilies is the fact that a substantial number of children entering stepfamilies are born out of wedlock. A third of children entering stepfamilies do so after birth to an unmarried mother, a situation that is four times more common in black stepfamilies than white stepfamilies.1 Finally, the mode of entry into stepfamilies also varies drastically with the age of children: while a majority of preschoolers entering stepfamilies do so after nonmarital birth, the least frequent mode of entry for these young children (16%) fits the traditional conception of a stepfamily as formed 1 This calculation includes children born to cohabiting (but unmarried) parents. -

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean Prepared by: Dr. Godfrey St. Bernard The University of the West Indies St. Augustine Trinidad and Tobago Phone Contacts: 1-868-776-4768 (mobile) 1-868-640-5584 (home) 1-868-662-2002 ext. 2148 (office) E-mail Contacts: [email protected] [email protected] Prepared for: United Nations Division of Social Policy and Development Department of Economic and Social Affairs Program on the Family Date: May 23, 2003 Introduction Though an elusive concept, the family is a social institution that binds two or more individuals into a primary group to the extent that the members of the group are related to one another on the basis of blood relationships, affinity or some other symbolic network of association. It is an essential pillar upon which all societies are built and with such a character, has transcended time and space. Often times, it has been mooted that the most constant thing in life is change, a phenomenon that is characteristic of the family irrespective of space and time. The dynamic character of family structures, - including members’ status, their associated roles, functions and interpersonal relationships, - has an important impact on a host of other social institutional spheres, prospective economic fortunes, political decision-making and sustainable futures. Assuming that the ultimate goal of all societies is to enhance quality of life, the family constitutes a worthy unit of inquiry. Whether from a social or economic standpoint, the family is critical in stimulating the well being of a people. The family has been and will continue to be subjected to myriad social, economic, cultural, political and environmental forces that shape it. -

What Is a Child & Family Team Meeting?

What is a Child & Family Team When is a Child & Family Team Meeting Location and Time Meeting? Meeting Necessary? We believe that Child & Family Team Meetings should be conducted at a mutu- A Child & Family Team Meeting (CFT) is A child has been found to be at high risk. ally agreeable and accessible location/time a strength based meeting that brings to- A child is at risk of out of home place- that maximizes opportunities for family gether your family, natural supports, and ment. participation. Please let us know your pref- formal resources. The meeting is lead by a Prior to the removal of a child from his erences regarding the time and location of trained facilitator to ensure that all partici- home. your meeting. pants have an opportunity to be involved Prior to a placement change of a child and heard. The purpose of the meeting is already in care. You have the right to…. to address the needs of your family and to Have your rights explained to you in a Prior to a change in a child’s perma- manner which is clear build upon its strengths. The goal of the nency goal. process is to enable your child(ren) to re- When requested by a parent, social main safely at home whenever possible. Receive written information or interpre- worker, or youth. tation in your native language. When there are multiple agencies in- The purpose of the Child & volved. Read, review, and receive written infor- At other critical decision points. mation regarding your child’s record Family Team Meeting is upon request. -

Anthropology of Race 1

Anthropology of Race 1 Knowing Race John Hartigan What do we know about race today? Is it surprising that, after a hun- dred years of debate and inquiry by anthropologists, not only does the answer remain uncertain but also the very question is so fraught? In part, this reflects the deep investments modern societies have made in the notion of race. We can hardly know it objectively when it constitutes a pervasive aspect of our identities and social landscapes, determining advantage and disadvantage in a thoroughgoing manner. Yet, know it we do. Perhaps mis- takenly, haphazardly, or too informally, but knowledge claims about race permeate everyday life in the United States. As well, what we understand or assume about race changes as our practices of knowledge production also change. Until recently, a consensus was held among social scientists—predi- cated, in part, upon findings by geneticists in the 1970s about the struc- ture of human genetic variability—that “race is socially constructed.” In the early 2000s, following the successful sequencing of the human genome, counter-claims challenging the social construction consensus were formu- lated by geneticists who sought to support the role of genes in explaining race.1 This volume arises out of the fracturing of that consensus and the attendant recognition that asserting a constructionist stance is no longer a tenable or sufficient response to the surge of knowledge claims about race. Anthropology of Race confronts the problem of knowing race and the challenge of formulating an effective rejoinder both to new arguments and sarpress.sarweb.org COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 3 John Hartigan data about race and to the intense desire to know something substantive about why and how it matters. -

The Hmong Culture: Kinship, Marriage & Family Systems

THE HMONG CULTURE: KINSHIP, MARRIAGE & FAMILY SYSTEMS By Teng Moua A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree With a Major in Marriage and Family Therapy Approved: 2 Semester Credits _________________________ Thesis Advisor The Graduate College University of Wisconsin-Stout May 2003 i The Graduate College University of Wisconsin-Stout Menomonie, Wisconsin 54751 ABSTRACT Moua__________________________Teng_____________________(NONE)________ (Writer) (Last Name) (First) (Initial) The Hmong Culture: Kinship, Marriage & Family Systems_____________________ (Title) Marriage & Family Therapy Dr. Charles Barnard May, 2003___51____ (Graduate Major) (Research Advisor) (Month/Year) (No. of Pages) American Psychological Association (APA) Publication Manual_________________ (Name of Style Manual Used In This Study) The purpose of this study is to describe the traditional Hmong kinship, marriage and family systems in the format of narrative from the writer’s experiences, a thorough review of the existing literature written about the Hmong culture in these three (3) categories, and two structural interviews of two Hmong families in the United States. This study only gives a general overview of the traditional Hmong kinship, marriage and family systems as they exist for the Hmong people in the United States currently. Therefore, it will not cover all the details and variations regarding the traditional Hmong kinship, marriage and family which still guide Hmong people around the world. Also, it will not cover the ii whole life course transitions such as childhood, adolescence, adulthood, late adulthood or the aging process or life core issues. This study is divided into two major parts: a review of literature and two interviews of the two selected Hmong families (one traditional & one contemporary) in the Minneapolis-St. -

Convention on the Rights of the Child

Convention on the Rights of the Child Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989 entry into force 2 September 1990, in accordance with article 49 Preamble The States Parties to the present Convention, Considering that, in accordance with the principles proclaimed in the Charter of the United Nations, recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Bearing in mind that the peoples of the United Nations have, in the Charter, reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights and in the dignity and worth of the human person, and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Recognizing that the United Nations has, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the International Covenants on Human Rights, proclaimed and agreed that everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth therein, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, Recalling that, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations has proclaimed that childhood is entitled to special care and assistance, Convinced that the family, as the fundamental group of society and the natural environment for the growth and well-being of all its members and particularly children, should be afforded -

Kin Relationships

In H. T. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships (pp. 951-954). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Kin Relationships Kin relationships are traditionally defined as ties based on blood and marriage. They include lineal generational bonds (children, parents, grandparents, and great- grandparents), collateral bonds (siblings, cousins, nieces and nephews, and aunts and uncles), and ties with in-laws. An often-made distinction is that between primary kin (members of the families of origin and procreation) and secondary kin (other family members). The former are what people generally refer to as “immediate family,” and the latter are generally labeled “extended family.” Marriage, as a principle of kinship, differs from blood in that it can be terminated. Given the potential for marital break-up, blood is recognized as the more important principle of kinship. This entry questions the appropriateness of traditional definitions of kinship for “new” family forms, describes distinctive features of kin relationships, and explores varying perspectives on the functions of kin relationships. Questions About Definition Changes over the last thirty years in patterns of family formation and dissolution have given rise to questions about the definition of kin relationships. Guises of kinship have emerged to which the criteria of blood and marriage do not apply. Assisted reproduction is a first example. Births resulting from infertility treatments such as gestational surrogacy and in vitro fertilization with ovum donation challenge the biogenetic basis for kinship. A similar question arises for adoption, which has a history 2 going back to antiquity. Partnerships formed outside of marriage are a second example. Strictly speaking, the family ties of nonmarried cohabitees do not fall into the category of kin, notwithstanding the greater acceptance over time of consensual unions both formally and informally. -

Arabic Kinship Terms Revisited: the Rural and Urban Context of North-Western Morocco

Sociolinguistic ISSN: 1750-8649 (print) Studies ISSN: 1750-8657 (online) Article Arabic kinship terms revisited: The rural and urban context of North-Western Morocco Amina Naciri-Azzouz Abstract This article reports on a study that focuses on the different kinship terms collected in several places in north-western Morocco, using elicitation and interviews conducted between March 2014 and June 2015 with several dozens of informants aged between 8 and 80. The analysed data include terms from the urban contexts of the city of Tetouan, but most of them were gathered in rural locations: the small village of Bni Ḥlu (Fahs-Anjra province) and different places throughout the coastal and inland regions of Ghomara (Chefchaouen province). The corpus consists of terms of address, terms of reference and some hypocoristic and affective terms. KEYWORDS: KINSHIP TERMS, TERMS OF ADDRESS, VARIATION, DIALECTOLOGY, MOROCCAN ARABIC (DARIJA) Affiliation University of Zaragoza, Spain email: [email protected] SOLS VOL 12.2 2018 185–208 https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.35639 © 2019, EQUINOX PUBLISHING 186 SOCIOLINGUISTIC STUDIES 1 Introduction The impact of migration ‒ attributable to multiple and diverse factors depending on the period ‒ is clearly noticeable in northern Morocco. Migratory movements from the east to the west, from rural areas to urban centres, as well as to Europe, has resulted in a shifting rural and urban population in this region. Furthermore, issues such as the increasing rate of urbanization and the drop in mortality have altered the social and spatial structure of cities such as Tetouan and Tangiers, where up to the present time some districts are known by the name of the origin of the population who settled down there: e.g. -

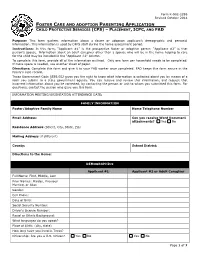

Foster Care and Adoption Parenting Application PDF Document

Form K-902-2286 Revised October 2014 FOSTER CARE AND ADOPTION PARENTING APPLICATION CHILD PROTECTIVE SERVICES (CPS) – PLACEMENT, ICPC, AND FAD Purpose: This form gathers information about a foster or adoption applicant’s demographic and personal information. This information is used by DFPS staff during the home assessment period. Instructions: In this form, “Applicant #1” is the prospective foster or adoptive parent. “Applicant #2” is that person’s spouse. Information about an adult caregiver other than a spouse who will be in the home helping to care for the child may be included in the “Applicant #2” column. To complete this form, provide all of the information outlined. Only one form per household needs to be completed. If more space is needed, use another sheet of paper. Directions: Complete this form and give it to your FAD worker once completed. FAD keeps this form secure in the family’s case record. Texas Government Code §559.002 gives you the right to know what information is collected about you by means of a form you submit to a state government agency. You can receive and review this information, and request that incorrect information about you be corrected, by contacting the person or unit to whom you submitted this form. For questions, contact the person who gave you this form. INFORMATION MEETING/ORIENTATION ATTENDANCE DATE: FAMILY INFORMATION Foster/Adoptive Family Name Home Telephone Number Email Address: Can you receive Word Document attachments? Yes No Residence Address (Street, City, State, Zip) Mailing Address (if different) County: School District: Directions to the Home: DEMOGRAPHICS Applicant #1 Applicant #2 or Adult Caregiver Full Name: First, Middle, Last Prior Names: Maiden, Previous Married, or Alias Gender: Cell Phone: Date of Birth: Social Security Number: Driver's License Number: Racial or Ethnic Background: What languages do you speak? Place of Birth: (city, state) How long have you lived in Texas? Citizenship: Are you a U.S.