Kin Relationships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

The Major Influences of the Boundless-Extended Family System on The

Fayetteville State University DigitalCommons@Fayetteville State University Faculty Working Papers from the School of School of Education Education Summer 2008 The aM jor Influences of the Boundless-Extended Family System on the Professional Experiences of Black Zimbabwean Women Leaders in Higher Education Miriam Chitiga Fayetteville State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uncfsu.edu/soe_faculty_wp Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Chitiga, Miriam, "The aM jor Influences of the Boundless-Extended Family System on the Professional Experiences of Black Zimbabwean Women Leaders in Higher Education" (2008). Faculty Working Papers from the School of Education. Paper 25. http://digitalcommons.uncfsu.edu/soe_faculty_wp/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at DigitalCommons@Fayetteville State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Working Papers from the School of Education by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fayetteville State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forum on Public Policy The Major Influences of the Boundless-Extended Family System on the Professional Experiences of Black Zimbabwean Women Leaders in Higher Education Miriam Miranda Chitiga, Claflin University, Orangeburg, South Carolina Abstract The article examines the major influences of the black Zimbabwean boundless- extended family system on the professional trajectories of women leaders working within the higher education system of Zimbabwe. The study is based on in-depth interviews conducted with thirty female leaders who shared information about their major family responsibilities. Using an analytical framework that facilitates a critical analysis of the evidence, the paper discusses the persisting significance of the interdependent systems of social stratification, namely race, nationality, gender, sexual orientation, and class in the private and public spheres of the female leaders. -

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean

Major Trends Affecting Families in Central America and the Caribbean Prepared by: Dr. Godfrey St. Bernard The University of the West Indies St. Augustine Trinidad and Tobago Phone Contacts: 1-868-776-4768 (mobile) 1-868-640-5584 (home) 1-868-662-2002 ext. 2148 (office) E-mail Contacts: [email protected] [email protected] Prepared for: United Nations Division of Social Policy and Development Department of Economic and Social Affairs Program on the Family Date: May 23, 2003 Introduction Though an elusive concept, the family is a social institution that binds two or more individuals into a primary group to the extent that the members of the group are related to one another on the basis of blood relationships, affinity or some other symbolic network of association. It is an essential pillar upon which all societies are built and with such a character, has transcended time and space. Often times, it has been mooted that the most constant thing in life is change, a phenomenon that is characteristic of the family irrespective of space and time. The dynamic character of family structures, - including members’ status, their associated roles, functions and interpersonal relationships, - has an important impact on a host of other social institutional spheres, prospective economic fortunes, political decision-making and sustainable futures. Assuming that the ultimate goal of all societies is to enhance quality of life, the family constitutes a worthy unit of inquiry. Whether from a social or economic standpoint, the family is critical in stimulating the well being of a people. The family has been and will continue to be subjected to myriad social, economic, cultural, political and environmental forces that shape it. -

Arabic Kinship Terms Revisited: the Rural and Urban Context of North-Western Morocco

Sociolinguistic ISSN: 1750-8649 (print) Studies ISSN: 1750-8657 (online) Article Arabic kinship terms revisited: The rural and urban context of North-Western Morocco Amina Naciri-Azzouz Abstract This article reports on a study that focuses on the different kinship terms collected in several places in north-western Morocco, using elicitation and interviews conducted between March 2014 and June 2015 with several dozens of informants aged between 8 and 80. The analysed data include terms from the urban contexts of the city of Tetouan, but most of them were gathered in rural locations: the small village of Bni Ḥlu (Fahs-Anjra province) and different places throughout the coastal and inland regions of Ghomara (Chefchaouen province). The corpus consists of terms of address, terms of reference and some hypocoristic and affective terms. KEYWORDS: KINSHIP TERMS, TERMS OF ADDRESS, VARIATION, DIALECTOLOGY, MOROCCAN ARABIC (DARIJA) Affiliation University of Zaragoza, Spain email: [email protected] SOLS VOL 12.2 2018 185–208 https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.35639 © 2019, EQUINOX PUBLISHING 186 SOCIOLINGUISTIC STUDIES 1 Introduction The impact of migration ‒ attributable to multiple and diverse factors depending on the period ‒ is clearly noticeable in northern Morocco. Migratory movements from the east to the west, from rural areas to urban centres, as well as to Europe, has resulted in a shifting rural and urban population in this region. Furthermore, issues such as the increasing rate of urbanization and the drop in mortality have altered the social and spatial structure of cities such as Tetouan and Tangiers, where up to the present time some districts are known by the name of the origin of the population who settled down there: e.g. -

Formal Analysis of Kinship Terminologies and Its Relationship to What Constitutes Kinship (Complete Text)

MATHEMATICAL ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURAL THEORY: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL VOLUME 1 NO. 1 PAGE 1 OF 46 NOVEMBER 2000 FORMAL ANALYSIS OF KINSHIP TERMINOLOGIES AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO WHAT CONSTITUTES KINSHIP (COMPLETE TEXT) 1 DWIGHT W. READ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90035 [email protected] Abstract The goal of this paper is to relate formal analysis of kinship terminologies to a better understanding of who, culturally, are defined as our kin. Part I of the paper begins with a brief discussion as to why neither of the two claims: (1) kinship terminologies primarily have to do with social categories and (2) kinship terminologies are based on classification of genealogically specified relationships traced through genitor and genetrix, is adequate as a basis for a formal analysis of a kinship terminology. The social category argument is insufficient as it does not account for the logic uncovered through the formalism of rewrite rule analysis regarding the distribution of kin types over kin terms when kin terms are mapped onto a genealogical grid. Any formal account must be able to account at least for the results obtained through rewrite rule analysis. Though rewrite rule analysis has made the logic of kinship terminologies more evident, the second claim must also be rejected for both theoretical and empirical reasons. Empirically, ethnographic evidence does not provide a consistent view of how genitors and genetrixes should be defined and even the existence of culturally recognized genitors is debatable for some groups. In addition, kinship relations for many groups are reckoned through a kind of kin term calculus independent of genealogical connections. -

Kinship Care: a New Kind of Family by Karen J

Health and Human Sciences HHS-788-W Kinship Care: A New Kind of Family By Karen J. Foli, PhD, RN, Associate Professor, Purdue University School of Nursing Have you noticed more middle-aged and older adults parenting young children? Perhaps you’ve seen these families in the grocery store, at school functions, or eating in restaurants. In the United States, a growing number of adult relatives and non-relatives are parenting children. They are providing what is known as kinship care. According to the Child Welfare League of What’s in a Name? America, kinship care is: Kinship parents and families have created new names for their types of families. Many of these the full time care, nurturing and protection families have several generations in them. Some of children by relatives, members of their of the more common names are: tribes or clans, godparents, stepparents, or any adult who has a kinship bond with a child. • kinship parents This definition is designed to be inclusive • grandfamilies and respectful of cultural values and ties • foster kinship care of affection. It allows a child to grow to • caring grandparents adulthood in a family environment. • fictive kinship Who Are Kinship Parents? Informal Care In Indiana, four percent of all children (59,000) live in public (foster) or private kinship care. Many kinship parents care for children without a Most often, it is a grandmother who is caring for formal arrangement. Unlike traditional families, a grandchild, but other adults may step in to help kinship families may have generations of family provide care when parents no longer can. -

Dna by the Entirety

DNA BY THE ENTIRETY Natalie Ram The law fails to accommodate the inconvenient fact that an individual’s identifiable genetic information is involuntarily and immutably shared with her close genetic relatives. Legal institutions have established that individuals have a cognizable interest in control- ling genetic information that is identifying to them. The Supreme Court recognized in Maryland v. King that the Fourth Amendment is impli- cated when arrestees’ DNA is analyzed, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act protects individuals from genetic discrimination in the employment and health-insurance markets. But genetic infor- mation is not like other forms of private or personal information because it is shared—immutably and involuntarily—in ways that are identifying of both the source and that person’s close genetic relatives. Standard approaches to addressing interests in genetic information have largely failed to recognize this characteristic, treating such infor- mation as individualistic. While many legal frames may be brought to bear on this problem, this Article focuses on the law of property. Specifically, looking to the law of tenancy by the entirety, this Article proposes one possible frame- work for grappling with the overlapping interests implicated in genetic identification and analysis. Tenancy by the entirety, like interests in shared identifiable genetic information, calls for the difficult task of conceptualizing two persons as one. The law of tenancy by the entirety thus provides a useful analytical framework for considering how legal institutions might take interests in shared identifiable genetic infor- mation into account. This Article examines how this framework may shape policy approaches in three domains: forensic identification, genetic research, and personal genetic testing. -

Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 104 | Issue 3 Article 4 2016 Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law Shelly Kreiczer-Levy College of Law and Business in Ramat Gan Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Family Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Laufer-Ukeles, Pamela and Kreiczer-Levy, Shelly (2016) "Family Formation and the Home," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 104 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol104/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles' & Shelly Kreiczer-Levj INTRODUCTION' In this article, we consider the relevance of home sharing in family formation. When couples or groups of persons are recognized as families, they are afforded significant benefits and given certain obligations by the law.4 Families have their own category of laws, rights, and obligations.' Currently, the law of family formation and recognition is in a state of flux. Although in some respects the defining legal lines of the family have been well settled for centuries around blood and the formal legal ties of marriage and parenthood, in significant ways, the family form has been fundamentally altered over the past few decades. -

Racial and Ethnic Differences in Extended Family, Friendship, Fictive Kin, and Congregational Informal Support Networks

ROBERT JOSEPH TAYLOR University of Michigan ∗ LINDA M. CHATTERS University of Michigan ∗∗ AMANDA TOLER WOODWARD Michigan State University ∗∗∗ EDNA BROWN University of Connecticut Racial and Ethnic Differences in Extended Family, Friendship, Fictive Kin, and Congregational Informal Support Networks This study examined differences in kin and Black Caribbeans had larger fictive kin networks nonkin networks among African Americans, than non-Hispanic Whites, but non-Hispanic Caribbean Blacks (Black Caribbeans), and non- Whites with fictive kin received support from Hispanic Whites. Data are taken from the them more frequently than African Americans National Survey of American Life, a nation- and Black Caribbeans. The discussion notes ally representative study of African Americans, the importance of examining kin and nonkin net- Black Caribbeans, and non-Hispanic Whites. works, as well as investigating ethnic differences Selected measures of informal support from within the Black American population. family, friendship, fictive kin, and congregation/ church networks were utilized. African Ameri- Involvement with kin and nonkin is an cans were more involved in congregation net- essential component of daily life for the vast works, whereas non-Hispanic Whites were more majority of Americans. Family and friendship involved in friendship networks. African Ameri- support networks are important for coping cans were more likely to give support to extended with the ongoing stresses of daily life (e.g., family members and to have daily interaction Benin & Keith, 1995), providing a place to with family members. African Americans and live when confronting homelessness (Taylor, Chatters, & Celious, 2003), and in coping with physical and mental health problems School of Social Work, 1080 South University Avenue, Ann (Cohen, Underwood, & Gottlieb, 2000; Lincoln, Arbor, MI 48109-1106 ([email protected]). -

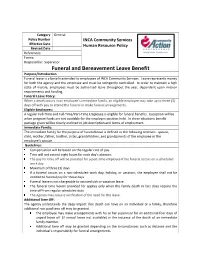

Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral Leave Is a Benefit Extended to Employees of INCA Community Services

Category General Policy Number INCA Community Services Effective Date Human Resource Policy Revised Date References: Forms: Responsible: Supervisor Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral leave is a benefit extended to employees of INCA Community Services. Leave represents money for both the agency and the employee and must be stringently controlled. In order to maintain a high state of morale, employees must be authorized leave throughout the year, dependent upon mission requirements and funding. Funeral Leave Policy: When a death occurs in an employee’s immediate family, an eligible employee may take up to three (3) days off with pay to attend the funeral or make funeral arrangements. Eligible Employees: A regular Full-Time and Full-Time/Part-Time Employee is eligible for funeral benefits. Exception will be when program funds are not available for the employee position held. In these situations benefit package given will be clearly outlined in job description and terms of employment. Immediate Family: The immediate family for the purpose of funeral leave is defined as the following relatives: spouse, child, mother, father, brother, sister, grandchildren, and grandparents of the employee or the employee’s spouse. Guidelines: Compensation will be based on the regular rate of pay. Time will not exceed eight hours for each day’s absence. The pay for time off will be prorated for a part-time employee if the funeral occurs on a scheduled work day. Maximum of three (3) days. If a funeral occurs on a non-scheduled work day, holiday, or vacation, the employee shall not be entitled to funeral pay for those days. -

The Reproductive Decision-Making of Women with Mitochondrial Disease

Julia Tonge Uncertain Existence: The reproductive decision-making of women with Mitochondrial Disease. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University October 2017 Abstract The aim of this thesis was to understand the process of reproductive decision- making in women with maternally inherited mitochondrial disease. It demonstrates the uncertainty fundamental to the experiences of women with mitochondrial DNA mutations (a subsection of women with mitochondrial disease). This uncertainty manifests in the personal accounts of their condition, as well as in relation to their reproductive decision-making. Twenty semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with eighteen women with mitochondrial DNA mutations, sampled via their connection to a mitochondrial disease specialist service in North East England. Retrospective, prospective and hypothetical questions were utilised in data collection. The data generated from the study, which was informed by constructivist grounded theory, can be organised into two central areas, both of which can be related back to uncertainty. The first area relates to how women harbour the desire for a healthy biologically related child. The second area features decision-making, which within the context of maternally inherited mitochondrial disease, is essentially the process by which women consolidate their desires for healthy children, and how they negotiate risk. The women’s accounts highlight social aspects of uncertainty that features in their reproductive decision-making, in contrast to the current literature that focuses on more clinical aspects of uncertainty. In addition, they also demonstrate how educational and employment institutions struggle to manage the uncertainty inherent in mitochondrial disease. -

Bereavement Leave

STATE OF CALIFORNIA - DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SERVICE PERSONNEL OPERATIONS MANUAL SUBJECT: BEREAVEMENT LEAVE REPRESENTED EMPLOYEES Bereavement leave allows for up to three (3) eight-hour days (24 hours) per occurrence or three (3) eight-hour days (24 hours) in a fiscal year based on the family member. The following chart describes the family member and bereavement leave allowed per bargaining unit. Bargaining Unit Eligible family member - three (3) eight-hour days Eligible family member - three (3) (24 hours) per occurrence eight-hour days (24 hours) in a fiscal year 1, 4, 11, 14, 15 • Parent • Aunt • Stepparent • Uncle • Spouse • Niece • Domestic Partner • Nephew • Child • immediate family members of • Grandchild Domestic Partners • Grandparent • Brother • Sister • Stepchild • Mother-in-Law • Father-in-Law • Daughter-in-Law • Son-in-Law • Sister-in-Law • Brother-in-Law • any person residing in the immediate household 2 • Parent • Grandchild • Stepparent • Grandparent • Spouse • Aunt • Domestic Partner • Uncle • Child • Niece • Sister • Nephew • Brother • Mother-in-Law • Stepchild • Father-in-Law • any person residing in the immediate household • Daughter-in-Law • Son-in-Law • Sister-in-Law • Brother-in-Law • immediate family member 7 • Parent • Grandchild • Stepparent • Grandparent • Spouse • Aunt • Domestic Partner • Uncle STATE OF CALIFORNIA - DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL SERVICE PERSONNEL OPERATIONS MANUAL Bargaining Unit Eligible family member - three (3) eight-hour days Eligible family member - three (3) (24 hours) per occurrence eight-hour