R. Brumbaugh Kinship Analysis: Methods, Results and the Sirionó Demonstration Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Evolution in Cultural Anthropology

UC Berkeley Anthropology Faculty Publications Title Evolution in Cultural Anthropology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pk146vg Journal American Anthropologist, 48(2) Author Lowie, Robert H. Publication Date 1946-06-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California EVOLUTION IN CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY: A REPLY TO LESLIE WHITE By ROBERT H. LOWIE LESLIE White's last three articles in the A merican A nthropologist1 require a reply since in my opinion they obscure vital issues. Grave matters, he clamors, are at stake. Obscurantists are plotting to defame Lewis H. Morgan and to undermine the theory of evolution. Professor White should relax. There are no underground machinations. Evolution as a scientific doctrine-not as a farrago of immature metaphysical notions-is secure. Morgan's place in the history of anthropology will turn out to be what he deserves, for, as Dr. Johnson said, no man is ever written down except by himself. These articles by White raise important questions. As a victim of his polemical shafts I should like to clarify the issues involved. I premise that I am peculiarly fitted to enter sympathetically into my critic's frame of mind, for at one time I was as devoted to Ernst Haeckel as White is to Morgan. Haeckel had solved the riddles of the universe for me. ESTIMATES OF MORGAN Considering the fate of many scientific men at the hands of their critics, it does not appear that Morgan has fared so badly. Americans bestowed on him the highest honors during his lifetime, eminent European scholars held him in esteem. -

Kin Relationships

In H. T. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships (pp. 951-954). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Kin Relationships Kin relationships are traditionally defined as ties based on blood and marriage. They include lineal generational bonds (children, parents, grandparents, and great- grandparents), collateral bonds (siblings, cousins, nieces and nephews, and aunts and uncles), and ties with in-laws. An often-made distinction is that between primary kin (members of the families of origin and procreation) and secondary kin (other family members). The former are what people generally refer to as “immediate family,” and the latter are generally labeled “extended family.” Marriage, as a principle of kinship, differs from blood in that it can be terminated. Given the potential for marital break-up, blood is recognized as the more important principle of kinship. This entry questions the appropriateness of traditional definitions of kinship for “new” family forms, describes distinctive features of kin relationships, and explores varying perspectives on the functions of kin relationships. Questions About Definition Changes over the last thirty years in patterns of family formation and dissolution have given rise to questions about the definition of kin relationships. Guises of kinship have emerged to which the criteria of blood and marriage do not apply. Assisted reproduction is a first example. Births resulting from infertility treatments such as gestational surrogacy and in vitro fertilization with ovum donation challenge the biogenetic basis for kinship. A similar question arises for adoption, which has a history 2 going back to antiquity. Partnerships formed outside of marriage are a second example. Strictly speaking, the family ties of nonmarried cohabitees do not fall into the category of kin, notwithstanding the greater acceptance over time of consensual unions both formally and informally. -

CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: the Man and His Works

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 1977 CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works Susan M. Voss University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Voss, Susan M., "CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works" (1977). Nebraska Anthropologist. 145. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/145 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in THE NEBRASKA ANTHROPOLOGIST, Volume 3 (1977). Published by the Anthropology Student Group, Department of Anthropology, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588 21 / CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works by Susan M. Voss 'INTRODUCTION "Claude Levi-Strauss,I Professor of Social Anth- ropology at the College de France, is, by com mon consent, the most distinguished exponent ~f this particular academic trade to be found . ap.ywhere outside the English speaking world ... " (Leach 1970: 7) With this in mind, I am still wondering how I came to be embroiled in an attempt not only to understand the mul t:ifaceted theorizing of Levi-Strauss myself, but to interpret even a portion of this wide inventory to my colleagues. ' There is much (the maj ori ty, perhaps) of Claude Levi-Strauss which eludes me yet. To quote Edmund Leach again, rtThe outstanding characteristic of his writing, whether in French or in English, is that it is difficul tto unders tand; his sociological theories combine bafflingcoinplexity with overwhelm ing erudi tion"., (Leach 1970: 8) . -

Flexibility in Hare Social Organization

FLEXlBILITY IN HARE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION ¹ GUY LANOUE Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 100 St. George St., Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 1A1 ABSTRACT/RESUME The Hare Indians of the NWT are characterized in terres of domestic groupe by two conflicting bases: those of the sibling groups which must co-operate, and those of conjugal units. The importance of both types of allegiances naturally creates a degree of tension and imposes care upon the negotiation of allegiances. La société des Indiens Hare des Territoires du Nord-Ouest est caractérisée par la présence de deux structures familiales en conflit: celle des enfants d'une morne famille, obligées à coopérer entre eux, et celle imposée par les liens conjugaux. La présence de ces deux orientations de ridE.litS crée naturel.lement chez les membres de cette société une certaine tendon et exige qu'ils portent à cet aspect de leurs relations une attention constante. 260 GUY LANOUE INTRODUCTION One striking feature of the anthropological descriptions of Athabascan Indian bands with bilateral, bifurcate-merging kinship terminology is the apparent lack of definite structurally-produced ru.les which might serve to provide an orientation for an individual's social action (cf. Helm 1956:131; Savashinsky 1974:xv, 194). The flexibility and negotiability of social relationships that usually appear to be associated with such systems are hot seen as positive features resulting from tendencies produced by structural regularities but rather are characterized as being the product of an absence of well defined sociologial reference points for the individual actor. This "definition by absence" does not appear to provide any useful insights into Athabascan social structure, as anthropological observers readily adroit that this negotiable feature of social relation- ships varies with the type of kin involved in the bilaterally-defined universe (cf. -

Dna by the Entirety

DNA BY THE ENTIRETY Natalie Ram The law fails to accommodate the inconvenient fact that an individual’s identifiable genetic information is involuntarily and immutably shared with her close genetic relatives. Legal institutions have established that individuals have a cognizable interest in control- ling genetic information that is identifying to them. The Supreme Court recognized in Maryland v. King that the Fourth Amendment is impli- cated when arrestees’ DNA is analyzed, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act protects individuals from genetic discrimination in the employment and health-insurance markets. But genetic infor- mation is not like other forms of private or personal information because it is shared—immutably and involuntarily—in ways that are identifying of both the source and that person’s close genetic relatives. Standard approaches to addressing interests in genetic information have largely failed to recognize this characteristic, treating such infor- mation as individualistic. While many legal frames may be brought to bear on this problem, this Article focuses on the law of property. Specifically, looking to the law of tenancy by the entirety, this Article proposes one possible frame- work for grappling with the overlapping interests implicated in genetic identification and analysis. Tenancy by the entirety, like interests in shared identifiable genetic information, calls for the difficult task of conceptualizing two persons as one. The law of tenancy by the entirety thus provides a useful analytical framework for considering how legal institutions might take interests in shared identifiable genetic infor- mation into account. This Article examines how this framework may shape policy approaches in three domains: forensic identification, genetic research, and personal genetic testing. -

Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 104 | Issue 3 Article 4 2016 Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law Shelly Kreiczer-Levy College of Law and Business in Ramat Gan Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Family Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Laufer-Ukeles, Pamela and Kreiczer-Levy, Shelly (2016) "Family Formation and the Home," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 104 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol104/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles' & Shelly Kreiczer-Levj INTRODUCTION' In this article, we consider the relevance of home sharing in family formation. When couples or groups of persons are recognized as families, they are afforded significant benefits and given certain obligations by the law.4 Families have their own category of laws, rights, and obligations.' Currently, the law of family formation and recognition is in a state of flux. Although in some respects the defining legal lines of the family have been well settled for centuries around blood and the formal legal ties of marriage and parenthood, in significant ways, the family form has been fundamentally altered over the past few decades. -

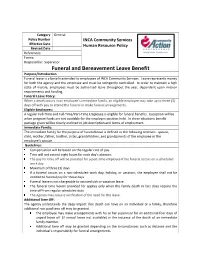

Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral Leave Is a Benefit Extended to Employees of INCA Community Services

Category General Policy Number INCA Community Services Effective Date Human Resource Policy Revised Date References: Forms: Responsible: Supervisor Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral leave is a benefit extended to employees of INCA Community Services. Leave represents money for both the agency and the employee and must be stringently controlled. In order to maintain a high state of morale, employees must be authorized leave throughout the year, dependent upon mission requirements and funding. Funeral Leave Policy: When a death occurs in an employee’s immediate family, an eligible employee may take up to three (3) days off with pay to attend the funeral or make funeral arrangements. Eligible Employees: A regular Full-Time and Full-Time/Part-Time Employee is eligible for funeral benefits. Exception will be when program funds are not available for the employee position held. In these situations benefit package given will be clearly outlined in job description and terms of employment. Immediate Family: The immediate family for the purpose of funeral leave is defined as the following relatives: spouse, child, mother, father, brother, sister, grandchildren, and grandparents of the employee or the employee’s spouse. Guidelines: Compensation will be based on the regular rate of pay. Time will not exceed eight hours for each day’s absence. The pay for time off will be prorated for a part-time employee if the funeral occurs on a scheduled work day. Maximum of three (3) days. If a funeral occurs on a non-scheduled work day, holiday, or vacation, the employee shall not be entitled to funeral pay for those days. -

Reconsidering Clan in Tibet

Are We Legend? Reconsidering Clan in Tibet Jonathan Samuels (University of Heidelberg) 1. Introduction ibetan Studies is relatively familiar with the theme of clan. The so-called “Tibetan ancestral clans” regularly feature in T works of Tibetan historiography, and have been the subject of several studies.1 Dynastic records and genealogies, often labelled “clan histories,” have been examined, and attempts have been made to identify ancient Tibetan clan territories.2 Various ethnographic and anthropological studies have also dealt both with the concept of clan membership amongst contemporary populations and a supposed Tibetan principle of descent, according to which the “bone”- substance (rus pa), the metonym for clan, is transmitted from father to progeny.3 Can it be said, however, that we have a coherent picture of clan in Tibet, particularly from a historical perspective? The present article has two aims. Firstly, by probing the current state of our understanding, it draws attention to key unanswered questions pertaining to clans and descent, and attempts to sharpen the discussion surrounding them. Secondly, exploring new avenues of research, it considers the extent to which we may distinguish between idealised representation and social reality within relevant sections of traditional hagiographical literature. 2. Current Understanding: Anthropological Studies and their Relevance Current understanding of Tibetan clans and descent rules has been 4 informed by several anthropological studies, including those of 1 Stein 1961; Karmay [1986] 1998; Vitali 2003. 2 Dotson 2012. 3 Oppitz 1973; Aziz 1974; Levine 1984. 4 The “current understanding” referred to here is that prevalent amongst members of the Tibetan Studies community; I address the way that evidence from Jonathan Samuels, “Are We Legend? Reconsidering Clan in Tibet,” Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, no. -

The Reproductive Decision-Making of Women with Mitochondrial Disease

Julia Tonge Uncertain Existence: The reproductive decision-making of women with Mitochondrial Disease. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Neuroscience, Newcastle University October 2017 Abstract The aim of this thesis was to understand the process of reproductive decision- making in women with maternally inherited mitochondrial disease. It demonstrates the uncertainty fundamental to the experiences of women with mitochondrial DNA mutations (a subsection of women with mitochondrial disease). This uncertainty manifests in the personal accounts of their condition, as well as in relation to their reproductive decision-making. Twenty semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with eighteen women with mitochondrial DNA mutations, sampled via their connection to a mitochondrial disease specialist service in North East England. Retrospective, prospective and hypothetical questions were utilised in data collection. The data generated from the study, which was informed by constructivist grounded theory, can be organised into two central areas, both of which can be related back to uncertainty. The first area relates to how women harbour the desire for a healthy biologically related child. The second area features decision-making, which within the context of maternally inherited mitochondrial disease, is essentially the process by which women consolidate their desires for healthy children, and how they negotiate risk. The women’s accounts highlight social aspects of uncertainty that features in their reproductive decision-making, in contrast to the current literature that focuses on more clinical aspects of uncertainty. In addition, they also demonstrate how educational and employment institutions struggle to manage the uncertainty inherent in mitochondrial disease. -

Nature and Society: Anthropological Perspectives

Nature and Society Nature and Society looks critically at the nature/society dichotomy—one of the central dogmas of western scholarship— and its place in human ecology and social theory. Rethinking the dualism means rethinking ecological anthropology and its notion of the relation between person and environment. The deeply entrenched biological and anthropological traditions which insist upon separating the two are challenged on both empirical and theoretical grounds. By focusing on a variety of perspectives, the contributors draw upon developments in social theory, biology, ethnobiology and sociology of science. They present an array of ethnographic case studies—from Amazonia, the Solomon Islands, Malaysia, the Moluccan Islands, rural communities in Japan and north-west Europe, urban Greece and laboratories of molecular biology and high-energy physics. The key focus of Nature and Society is the issue of the environment and its relations to humans. By inviting concern for sustainability, ethics, indigenous knowledge and the social context of science, this book will appeal to students of anthropology, human ecology and sociology. Philippe Descola is Directeur d’Etudes, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, Paris, and member of the Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale at the Collège de France. Gísli Pálsson is Professor of Anthropology at the University of Iceland, Reykjavik, and (formerly) Research Fellow at the Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study in the Social Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden. European Association of Social Anthropologists The European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA) was inaugurated in January 1989, in response to a widely felt need for a professional association which would represent social anthropologists in Europe and foster co-operation and interchange in teaching and research. -

Solving Alliance Cohesion

SOLVING ALLIANCE COHESION: NATO COHESION AFTER THE COLD WAR A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Mark M. Mecum June 2007 This thesis titled SOLVING ALLIANCE COHESION: NATO COHESION AFTER THE COLD WAR by MARK M. MECUM has been approved for the Department of Political Science and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patricia A. Weitsman Professor of Political Science Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Abstract MECUM, MARK M., M.A., June 2007, Political Science SOLVING ALLIANCE COHESION: NATO COHESION AFTER THE COLD WAR (198 pp.) Director of Thesis: Patricia A. Weitsman Why does NATO remain a cohesive alliance in the post-Cold War era? This question, which has bewildered international relations scholars for years, can tell us a lot about institutional dynamics of alliances. Since traditional alliance theory indicates alliances form to counter threat or power, it is challenging to understand how and why NATO continues to exist after its founding threat and power – communism and the USSR – no longer exist. The fluctuation of cohesion in NATO since the end of the Cold War will be examined to determine how cohesion is forged and maintained. To achieve this, alliance theories will be fused into a clear and understandable model to measure cohesion. Approved: Patricia A. Weitsman Professor of Political Science Acknowledgments The political science and history faculty at Ohio University showed me the entrance to the study of world politics. I appreciate the instruction and international internship opportunity that the political science department gave me as a young undergraduate student.