THE METALLURGY of SOME INDIAN SWORDS from the Arsenal of Hyderabad and Elsewhere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records of the Medieval Sword Free

FREE RECORDS OF THE MEDIEVAL SWORD PDF Ewart Oakeshott | 316 pages | 15 May 2015 | Boydell & Brewer Ltd | 9780851155661 | English | Woodbridge, United Kingdom Records of the Medieval Sword by Ewart Oakeshott, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® I would consider this the definitive work on the development of the form, design, and construction of the medieval sword. Oakeshott was the foremost authority on the subject, and this work formed the capstone of his career. Anyone with a serious interest in European swords should own this book. Records of the Medieval Sword. Ewart Oakeshott. Forty years of intensive research into the specialised subject of the straight two- edged knightly sword of the European middle ages are contained in this classic study. Spanning the period from the great migrations to the Renaissance, Ewart Oakeshott emphasises the original purpose of the sword as an intensely intimate accessory of great significance and mystique. There are over photographs and drawings, each fully annotated and described in detail, supported by a long introductory chapter with diagrams of the typological framework first presented in The Archaeology of Weapons and further elaborated in The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. There are appendices on inlaid blade inscriptions, scientific dating, the swordsmith's art, and a sword of Edward Records of the Medieval Sword. Reprinted as part Records of the Medieval Sword Boydell's History of the Sword series. Records of the Medieval Sword - Ewart Oakeshott - Google книги Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. -

Weapon Group Feats for Pathfinder: Class: Weapon Group Proficiencies

Weapon Group Feats for Pathfinder: Class: Weapon Group Proficiencies at 1st Level: Alchemist Basic weapons, Natural, Crossbows, any other 1 Barbarian Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Bard Basic weapons, Natural, any other 3 Cavalier Basic weapons, Natural, Spears, any other 3 Cleric Basic weapons, Natural, deity’s weapon group, any other 2(3 groups if not following a deity) Druid Basic weapons, Natural, druid weapons, any other 1 Fighter Basic weapons, Natural, any other 5 Gunslinger Basic weapons, Natural, firearms, any other 3 Monk Basic weapons, and all monk weapons Inquisitor Basic weapons, Natural, deity’s weapon group, Bows or Crossbows, any other 3 (4 groups if not following a deity) Magus Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Oracle Basic weapons, Natural, any other 1 (+3 if taking Skill at Arms) Paladin/AntiPaladin Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Ranger Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Rogue Basic weapons, Natural, any other 3 Sorcerer Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows , any other 1 Summoner Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows , any other 1 Witch Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows , any other 1 Wizard Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows This system doesn’t change Racial Weapon Familiarity. Weapon Group Name: Weapons In Group: Axes bardiche, battleaxe, dwarven waraxe, greataxe, handaxe, heavy pick, hooked axe, knuckle axe, light pick, mattock, orc double axe, pata, and throwing axe Basic club, dagger, quarterstaff, and sling Blades, Heavy bastard sword, chakram, double chicken saber, double -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Knights at the Museum Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation

Knights! At the Museum Knights at the Museum Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the faculty of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in fulfillment of the requirements for graduation. By: Jonathan Blythe, Thomas Cieslewski, Derek Johnson, Erich Weltsek Faculty Advisor: Jeffrey Forgeng JLS IQP 0073 March 6, 2015 1 Knights! At the Museum Contents Knights at the Museum .............................................................................................................................. 1 Authorship: .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract: ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction to Metallurgy ...................................................................................................................... 12 “Bloomeries” ......................................................................................................................................... 13 The Blast Furnace ................................................................................................................................. 14 Techniques: Pattern-welding, Piling, and Quenching ...................................................................... -

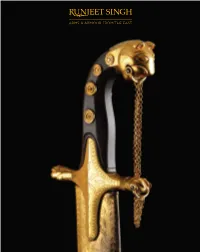

Viewings by Appointment Only 6

+44 (0)7866 424 803 [email protected] runjeetsingh.com CONTENTS Daggers 6 Swords 36 Polearms 62 Firearms 74 Archery 84 Objects 88 Shields 98 Helmets 104 Written by Runjeet Singh Winter 2015 All prices on request Viewings by appointment only 6 1 JAAM-DHAR An important 17th century Indian A third and fourth example are (DEMONS TOOTH) katar (punch dagger) from the published by Elgood 2004, p.162 KATAR Deccan plateau, possibly Golkonda (no.15.39) and Egerton (no.388), (‘shepherd’s hill’), a fort of Southern from Deccan and Lucknow India and capital of the medieval respectively. Both are late 17th DECCAN (SOUTH INDIA) sultanate of the Qutb Shahi dynasty or early 18th century and again 17TH CENTURY (c.1518–1687). follow the design of the katar in this exhibition. OVERALL 460 MM This rare form of Indian katar is the BLADE 280 MM earliest example known from a small The heavy iron hilt has intricate group, examples of which are found piercing and thick silver sheet is in a number of notable collections. applied overall. These piercing, These include no.133 in Islamic suggestive of flower patterns, softens Arms & Armour from Danish private the austerity of the design which Collections, dated to the early 18th can be related to architecture, for century. Probably Deccani in origin, example the flared side bars have the arabesques on the blade have tri-lobed ends. The architectural Shi’ite calligraphy. The features of this theme continues into the lower bar fine katar are closely related to the which connects to the blade; this has katar published here. -

To Interpret the Meaning of the Five Ks for Sikhs Around the World Activity

Lesson Three LI: To interpret the meaning of the five Ks for Sikhs around the world Activity Read through the following slides and look the weblinks. Draw and describe the importance of each of the five Ks for Sikhs. • https://www.bbc.com/teach/class-clips- video/the-five-ks-in-sikhism/znbhf4j • https://www.bbc.com/bitesize/clips/zbfgkqt • https://www.bbc.com/bitesize/clips/zcn34wx • https://www.bbc.com/bitesize/clips/z3sb9j6 A Sense of Belonging Sikhism and the five Ks Guru Gobind Singh The Story of Guru Gobind Singh and the Five Ks There are ten human Gurus and Guru Gobind Singh is the last one. A long time ago terrible things were happening to Sikhs in India and so Guru Gobind Singh decided to do something about it. One day in a place called Anandpur the Guru gathered the Sikhs to celebrate their harvest festival. At the festival he called for a man who was willing to die for his faith. Soon one man stepped forward and went into a tent with the Guru. Then the Guru reappeared with blood on his sword. He then asked for another volunteer and another man went into the tent with the Guru. Once again the Guru came out of the tent with his sword covered in blood. So two men went in and did not come out again. The Guru then asked for a third volunteer and the same thing happened. He asked for a fourth volunteer and again reappeared with blood on his sword. He then asked for a fifth volunteer and again the Guru reappeared with blood on his sword. -

Drawing Across Boundaries Designing a Devanagari Typeface in the UK Drawing Designing a Across Devanagari Typeface Boundaries in the UK

Drawing Across Boundaries Designing a Devanagari Typeface in the UK drawing designing a across Devanagari typeface boundaries in the UK Erin McLaughlin MATD, University of Reading, UK Hoefler & Frere-Jones, NYC » + ¿ æ ‰…;€ «¬!?» ~ katari ˆ`ˇ Erin McLaughlin ©2010 [email protected] ‡ ˘{>,+[´:’/ } English A Kattari, Katara or Katar (Devanāgarī: कटार, ka��āri, ka�āra), also known as a suwaiya or Bundi dagger, is a type of short punching sword that originated in South India as “Kattari” and spread throughout India. It is used to make swift and quick attacks. It is notable for its horizontal hand grip, which results in the blade of the sword sitting above the user’s knuckles. Three other examples of bladed weapons native and unique to India are the Khanda, Urumi and Pata. The Kattari is one of the oldest and most characteristic of the Indian knife weapons. Its peculiarity lies in the handle which is made up of two paral- lel bars connected by two, or more, cross piec- es, one of which is at the end of the side bars Spanish El Katar es un arma blanca, usada en Persia y en el norte de la India. Consiste en una Katari Regular daga de hoja ancha con una empuñadura lateral, que hace que la hoja continúe la línea aá[ăfiâä^æǽ²àā|ąãå�bc]ćč−çĉċd ď₉đ�£eéĕ æ aá[ăff âä^æâä^ del antebrazo en lugar de quedar perpen- aá[ăff dicular a él. Ésta se sujeta por medio de un ěflêëė7èēẽ�ęfgğ⁹⁄₁₀ĝģġ~ğĝ�\hħĥ�i�íĭîï⁽⁰⁾ìĩī guante al que va sujeta y que se acopla a la įij$jĵkķ�ĸl;ĺ.ľ�ļ⁶�ŀłmṁ‹nʼnfj ń›ň¬ņñ��ņ mano y se sujeta por medio de cuerdas o diversas ataduras al antebrazo, para así darle ṅo€ó×ŏ6ôö'œòő>ōø"ǿõpqr&ŕřŗ���s=śš şŝṡ un mayor agarre. -

Sample File Gladius: Double-Edged Sword of Roman Design Between 65 and 70 Cm Long

he sword has been an iconic weapon in role-playing games from the earliest days. Who Thasn’t played a game where at least one player played a character wielding a mighty sword — be it a simple longsword, heavy bastard sword, versatile short sword, massive two-handed sword, or dextrous rapier? Swords, in their many flavors and varieties have filled the pages of role-playing games, fantasy books, and other writings for generations. But when you play your games, whether set in far off fantasy lands or in Norman England, do your swords all look alike? What sets one longsword apart from another? Sure, they all do the same amount of damage, but what makes them special? Swords have been around in human history since the Bronze Age, or maybe even earlier. They reached their height of variety and versatility in the European Middle Ages and have found a place among the armies of the world, stretching across Europe, Africa, and Asia. In basic terms, a sword is a bladed (edged) weapon used for cutting and thrusting. The exact definition, style, and name depends on which age of history you are examining and the culture that created the weapon. From saifs, daos, khopesh, katanas, spatha, talwar, and Viking swords to Norman Longswords, Zweihanders, scimitars, rapiers, epee, and cavalry sabers, swords have found a place in our history. These weapons were all designed to meet a specific need for the wielder - whether functional or emotional or both. From purely utilitarian functionality to great works of art, swords run the gamut of form and function, which is probably why they are so important in role-playing games. -

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605 A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew de la Garza Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor; Stephen Dale; Jennifer Siegel Copyright by Andrew de la Garza 2010 Abstract This doctoral dissertation, Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, examines the transformation of warfare in South Asia during the foundation and consolidation of the Mughal Empire. It emphasizes the practical specifics of how the Imperial army waged war and prepared for war—technology, tactics, operations, training and logistics. These are topics poorly covered in the existing Mughal historiography, which primarily addresses military affairs through their background and context— cultural, political and economic. I argue that events in India during this period in many ways paralleled the early stages of the ongoing “Military Revolution” in early modern Europe. The Mughals effectively combined the martial implements and practices of Europe, Central Asia and India into a model that was well suited for the unique demands and challenges of their setting. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to John Nira. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John F. Guilmartin and the other members of my committee, Professors Stephen Dale and Jennifer Siegel, for their invaluable advice and assistance. I am also grateful to the many other colleagues, both faculty and graduate students, who helped me in so many ways during this long, challenging process. -

Arts Des Guerriers Dorient.Pdf

ARTS OF THE ORIENTAL WARRIOR SEPTEMBER 2018 PARIS +44 (0)7866 424 803 [email protected] runjeetsingh.com INTRODUCTION This catalogue accompanies As the title of my show I hope readers of the My heartfelt thanks go to my first solo exhibition in suggests, I want to catalogue, and those who the many people who have Paris and is entitled Arts des demonstrate not only the visit the exhibition, will worked with me behind the Guerriers d’Orient—Arts of artistic qualities of these find the information I have scenes and who make such the Oriental Warrior. I will implements of war but also provided to be useful and events and publications so be exhibiting alongside some that arms and armour were enjoy the aesthetics of these successful. of the world’s best tribal in some cases presentation visually striking objects (often dealers at the well-known fair items or status symbols for an important reason for their Runjeet Singh Parcours des Mondes which owners who were often inclusion). is accumulating a strong powerful and important. following in the Asian art market. Ce catalogue accompagne Comme le titre de mon J'espère que les lecteurs de Mes sincères remerciements ma première exposition exposition le suggère, je veux ce catalogue, ainsi que ceux aux nombreuses personnes solo à Paris et s'intitule Arts non seulement mettre en qui visiteront l'exposition, en qui ont travaillé avec moi des Guerriers d'Orient – avant les qualités artistiques trouveront les informations en coulisses et qui font le Art of the Oriental Warrior. de ces équipements militaires, utiles et apprécieront succès de tels évènements et Je m'apprête à exposer mais aussi le fait que les l'esthétique de ces objets au publications. -

EEWRS Green Y2K T Shirt

1 Bastard Sword (Hand and a Half Sword) German, late 20 Kattara Omani, 19th century. 14th century, bearing a dedicatory inscription from the 21 Sword Flemish, mid to late 15th century (type XVIII). Alexandria Arsenal (type XIIa). 22 Kaskara (Sudanic Africa), late 19th century. 2 Sword (Western Europe), 11th century, with simple disk pommel (type Xa). 23 Sword (Western Europe), 9th to 10th century (type H). 3 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), 20th century. 24 Sword (Western Europe), 9th to 10th century 4 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), 20th century. (type H). 5 Sword with talwar style hilt and a khanda style 25 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), 20th blade (India), 19th century. century. 6 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), 19th 26 Riding Sword French, 13th century. century, likely with an earlier blade. 27 Sword (Western Europe), 10th century 7 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), 20th (type M). century. 28 Kattara Omani, 19th century. 8 Sword (Northwestern Europe), 10 to 11th century, with “tea-cosy” pommel and 29 Phirangi (Firangi) Hindu (Southern pattern-welded blade (type X). India), 17th century. 9 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), late 30 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), 20th century with an earlier blade. 20th century. 10 Kaskara (Sudanic Africa), 20th 31 Basket Hilted Broadsword British, century. 17th century with an earlier, possibly 14th century, blade. 11 Khanda Hindu (Southern India), 19th century. 32 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), 20th century. 12 Kaskara (Sudanic Africa), late 19th century. 33 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), 20th century. 13 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), 20th century. 34 Sword (Western Europe), 10th century (type K). 14 Takouba Tuareg (Saharan Africa), late 20th century with an earlier blade. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS