Central Welland River Watershed Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifying the Potential Sources of Contaminants to the Welland Canal, the Major Source of Drinking Water in the Niagara Region

Ryerson University Digital Commons @ Ryerson Theses and dissertations 1-1-2010 Identifying The otP ential Sources Of Contaminants To The elW land Canal, The aM jor Source Of Drinking Water In The iN agara Region Zahra Labbaf Ryerson University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ryerson.ca/dissertations Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Labbaf, Zahra, "Identifying The otP ential Sources Of Contaminants To The eW lland Canal, The aM jor Source Of Drinking Water In The iN agara Region" (2010). Theses and dissertations. Paper 1557. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Ryerson. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ryerson. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDENTIFYING THE POTENTIAL SOURCES OF CONTAMINANTS TO THE WELLAND CANAL, THE MAJOR SOURCE OF DRINKING WATER IN THE NIAGARA REGION by Zahra Labbaf Bachelor of Science, Shahid Chamran University, 2006 A thesis presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Applied Science in the Program of Environmental Applied Science and Management Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2010 © Zahra Labbaf, 2010 i I hereby declare that I am sole author of this thesis. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. Zahra Labbaf I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. -

Town of St. Joseph, Wisconsin Natural Areas Inventory/ Land Cover Mapping September 2016

Town of St. Joseph, Wisconsin Natural Areas Inventory/ Land Cover Mapping September 2016 Prepared for: Town of St. Joseph, Wisconsin Prepared by: Stantec Consulting Services Inc. TOWN OF ST. JOSEPH, WISCONSIN NATURAL AREAS INVENTORY/ LAND COVER MAPPING SEPTEMBER 2016 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. III 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................1.1 1.1 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES OF THE NRI .......................................................................... 1.1 2.0 A BRIEF LOOK AT THE NATURAL HISTORY OF THE STUDY AREA ..................................2.4 2.1 BEDROCK GEOLOGY AND GLACIAL LANDSCAPES .................................................. 2.4 2.2 AFTER THE GLACIERS ...................................................................................................... 2.4 2.3 INFLUENCE OF LANDFORM AND CLIMATE ON VEGETATION TYPES ......................... 2.9 2.4 PRE-HISTORIC INFLUENCE OF HUMANS ON THE LANDSCAPE ................................. 2.10 2.5 VEGETATION AT THE TIME OF LAND SURVEY ............................................................. 2.10 2.6 POST-SETTLEMENT INFLUENCES ON THE LANDSCAPE ............................................... 2.10 3.0 PROJECT METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................3.12 3.1 GATHER AND REVIEW BACKGROUND INFORMATION............................................ -

Vulnerability of the Biota in Riverine and Seasonally Flooded Habitats to Damming of Amazonian Rivers

Received: 11 December 2019 Revised: 8 April 2020 Accepted: 5 June 2020 DOI: 10.1002/aqc.3424 SPECIAL ISSUE ARTICLE Vulnerability of the biota in riverine and seasonally flooded habitats to damming of Amazonian rivers Edgardo M. Latrubesse1 | Fernando M. d'Horta2 | Camila C. Ribas2 | Florian Wittmann3 | Jansen Zuanon2 | Edward Park4 | Thomas Dunne5 | Eugenio Y. Arima6 | Paul A. Baker7 1Asian School of the Environment and Earth Observatory of Singapore (EOS), Nanyang Abstract Technological University (NTU), Singapore 1. The extent and intensity of impacts of multiple new dams in the Amazon basin on 2 National Institute of Amazonian Research specific biological groups are potentially large, but still uncertain and need to be (INPA), Manaus, Brazil 3Institute of Floodplain Ecology, Karlsruhe better understood. Institute of Technology, Rastatt, Germany 2. It is known that river disruption and regulation by dams may affect sediment sup- 4 National Institute of Education (NIE), plies, river channel migration, floodplain dynamics, and, as a major adverse conse- Nanyang Technological University, Singapore quence, are likely to decrease or even suppress ecological connectivity among 5Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California (UCSB), populations of aquatic organisms and organisms dependent upon seasonally Santa Barbara, California, USA flooded environments. 6Department of Geography and the Environment, University of Texas at Austin, 3. This article complements our previous results by assessing the relationships Austin, Texas, USA between dams, our Dam Environmental Vulnerability Index (DEVI), and the biotic 7 Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke environments threatened by the effects of dams. Because of the cartographic rep- University, Durham, North Carolina, USA resentation of DEVI, it is a useful tool to compare the potential hydrophysical Correspondence impacts of proposed dams in the Amazon basin with the spatial distribution of Edgardo Latrubesse, Asian School of the Environment and Earth Observatory of biological diversity. -

Temporal Change and Hydrological Model Parameterization of Coyle Creek

Temporal Change and Hydrological 2009 Model Parameterization of Coyle Creek DECEMBER 14TH, 2009 Temporal Change and Hydrological Model Parameterization of Coyle Creek Proposal 2009 December 14th, 2009 December 14th, 2009 Temporal Change and Hydrological 2009 Model Parameterization of Coyle Creek File No: 200910-13 GISC9314-Deliverable 5 Mr. Ian Smith, M.Sc., OLS, OLIP President, Geomorphologist LydIan Environmental Consulting 21 Longspur Circle Fonthill, ON L0S 1E2 Dear Mr. Smith, Re: Temporal Change and Historical Hydrologic Model Parameterization – Coyle Creek Watershed Proposal iL Mondo strives for the highest quality of services to deliver to our clients. We will provide outstanding results, the best solution for your problem at Coyle Creek and professional interactions with our clients. Please accept this letter as our formal proposal for LydIan Environmental Consulting on the Temporal Change and Historical Hydrologic Model Parameterization – Coyle Creek Watershed project. This proposal includes all the requirements LydIan Environmental Consulting has provided to us. This Proposal also includes the time length this project will take to complete which is approximately 340 hours, being complete by June 2nd, 2010. The budget for this project is estimated at $41,235. Please find time and cost management details attached. We have proposed all requirements that LydIan Environmental Consulting has requested from our company on this project. If you have any questions regarding the enclosed documents, please contact any project member at your convenience Lisa at (905) 818 8489, [email protected] or Rudy Stawarek at (905) 730-7020, [email protected]. Thank you for your time and attention. We look forward to hearing from you. -

The Welland River Eutrophication Study in the Niagara River Area of Concern in Support of the Beneficial Use Impairment: Eutrophication and Undesirable Algae

The Welland River Eutrophication Study in the Niagara River Area of Concern in Support of the Beneficial Use Impairment: Eutrophication and Undesirable Algae March 2011 Niagara River RAP Welland River Eutrophication Study Technical Working Group The Welland River Eutrophication Study in the Niagara River Area of Concern in Support of the Beneficial Use Impairment: Eutrophication and Undesirable Algae March 2011 Written by: Joshua Diamond Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority On behalf of: Welland River Eutrophication Technical Working Group The Welland River Eutrophication Study in the Niagara River Area of Concern in Support of the Beneficial Use Impairment: Eutrophication and Undesirable Algae Written By: Joshua Diamond Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority On Behalf: Welland River Eutrophication Technical Working Group Niagara River Remedial Action Plan For more information contact: Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority Valerie Cromie, Coordinator Niagara River Remedial Action Plan Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority 905-788-3135 [email protected] The Welland River Eutrophication Study in the Niagara River Area of Concern Welland River Eutrophication Study Technical Working Group Ilze Andzans Region Municipality of Niagara Valerie Cromie Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority Sarah Day Ontario Ministry of the Environment Joshua Diamond Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority Martha Guy Environment Canada Veronique Hiriart-Baer Environment Canada Tanya Labencki Ontario Ministry of the Environment Dan McDonell Environment -

NIAGARA ROCKS, BUILDING STONE, HISTORY and WINE

NIAGARA ROCKS, BUILDING STONE, HISTORY and WINE Gerard V. Middleton, Nick Eyles, Nina Chapple, and Robert Watson American Geophysical Union and Geological Association of Canada Field Trip A3: Guidebook May 23, 2009 Cover: The Battle of Queenston Heights, 13 October, 1812 (Library and Archives Canada, C-000276). The cover engraving made in 1836, is based on a sketch by James Dennis (1796-1855) who was the senior British officer of the small force at Queenston when the Americans first landed. The war of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States offers several examples of the effects of geology and landscape on military strategy in Southern Ontario. In short, Canada’s survival hinged on keeping high ground in the face of invading American forces. The mouth of the Niagara Gorge was of strategic value during the war to both the British and Americans as it was the start of overland portages from the Niagara River southwards around Niagara Falls to Lake Erie. Whoever controlled this part of the Niagara River could dictate events along the entire Niagara Peninsula. With Britain distracted by the war against Napoleon in Europe, the Americans thought they could take Canada by a series of cross-border strikes aimed at Montreal, Kingston and the Niagara River. At Queenston Heights, the Niagara Escarpment is about 100 m high and looks north over the flat floor of glacial Lake Iroquois. To the east it commands a fine view over the Niagara Gorge and river. Queenston is a small community perched just below the crest of the escarpment on a small bench created by the outcrop of the Whirlpool Sandstone. -

Lake Ontario

196 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 5 Chapter 6, Pilot Coast U.S. 76°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 6—Chapter 5 78°W 77°W NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 44°30'N 79°W Kingston ONTARIO 14802 Cape Vincent 44°N Sackets Harbor 14810 14811 Toronto L AKE ONTARIO CANADA UNITED STATES 14806 14813 43°30'N Oswego Point Breeze Harbor 14815 14814 LITTLE SODUS BAY 14803 SODUS BAY Hamilton 14816 14805 IRONDEQUOIT BAY Niagra Falls Rochester 14804 WELLAND CANAL 14832 43°N Bu alo 2042 NEW Y ORK 14833 19 SEP2021 L AKE ERIE 14822 19 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 5 ¢ 197 Lake Ontario (1) under the navigational control of the Saint Lawrence Chart Datum, Lake Ontario Seaway Development Corporation, a corporate agency of the United States, and the Saint Lawrence Seaway (2) Depths and vertical clearances under overhead cables Management Corporation of Canada. These agencies and bridges given in this chapter are referred to Low Water issue joint regulations covering vessels and persons using Datum, which for Lake Ontario is an elevation 243.3 feet the Seaway. The regulations are codified in33 CFR 401 (74.2 meters) above mean water level at Rimouski, QC, and are also contained in the Seaway Handbook, published on International Great Lakes Datum 1985 (IGLD 1985). jointly by the agencies. A copy of the regulations is (See Chart Datum, Great Lakes System, indexed as required to be kept on board every vessel transiting the such, chapter 3.) Seaway. -

A Guide to Celebrate Niagara Peninsula's Native Plants

A GUIDE TO CELEBRATE NIAGARA PENINSULA’S NATIVE PLANTS 250 Thorold Road West, 3rd Floor Welland, ON L3C 3W2 Phone: 905.788.3135 Fax: 905.788.1121 www.npca.ca Like us on Facebook www.facebook.com/NiagaraPeninsulaConservationAuthority Follow us on Twitter @NPCA_Ontario © 2014 Sixth Edition – Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority The Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority has made every attempt to ensure the accuracy of the information contained within this publication and is not responsible for any errors or omissions. The Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority warns consumers that it is not advisable to eat any of the fruits or plants described in this publication. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................2 to 5 Flowering Times and Bloom Colour ............................................................................6 to 7 Native Plant List .................................................................................................... 8 to 15 Dry Conditions - Sunny - Wildflowers ..................................................................... 16 to 22 Dry Conditions - Sunny - Grasses ....................................................................................23 Dry Conditions - Sunny - Trees ........................................................................................24 Moist to Wet Conditions - Sunny - Wildflowers ........................................................ 25 to 28 Moist to Wet Conditions -

Methodology and Application of a Statistical Approach to the Universal Soil Loss Equation (Usle): Welland River Case Study

Middle States Geographer, 1996, 29:105-113 METHODOLOGY AND APPLICATION OF A STATISTICAL APPROACH TO THE UNIVERSAL SOIL LOSS EQUATION (USLE): WELLAND RIVER CASE STUDY Shannon L. Vickers1 , Kim N. Irvine2, and Ian G. Droppo3 1. Department of Geography, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, L8S 4K1. 2. Department of Geography and Planning, State University College, Buffalo, NY 14222. 3. National Water Research Institute, Burlington, Ontario, Canada, L7R 4A6. ABSTRACI': The WeI/and River watershed drains an area of 880 km2 and is part of the Niagara River Area of Concem. As one step towards remediation, the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE) was used to estimate soil erosion inputs to the river from each of the 34 sub-basins in the watershed. An innovative approach using risk and uncertainty analysis was incorporated into the conventional USLE estimates in order to address concems about uncertainty due to the variability of the USLE parameters across the WeI/and River watershed. This paper describes the methodology for the statistical approach to the USLE and those sub-basins with high potential soil loss were identified. INTRODUCflON (USLE) was used to estimate soil erosion rates for each of the 34 sub-basins in the watershed. A risk and uncertainty analysis (including probability The Welland River watershed is part of the distribution fitting and simulations using Latin Niagara River Area of Concern. Areas of Concern Hypercube sampling) was incorporated into the around the Great Lakes have been designated by conventional USLE estimates and was performed the International Joint Commission (DC) as using BESTFIT and @RISK, which are EXCEL exhibiting various environmental impairments. -

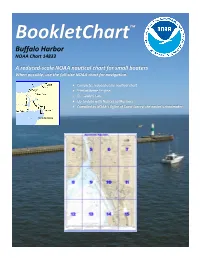

Bookletchart™ Buffalo Harbor NOAA Chart 14833

BookletChart™ Buffalo Harbor NOAA Chart 14833 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the The International boundary between the United States and Canada follows a general middle of the river course in the upper Niagara River National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration from the head of the river downstream to the head of Grand Island National Ocean Service where the river forks around the island. The boundary then follows Office of Coast Survey Chippawa Channel and is generally less than 1,000 feet off the west shore of Grand Island until Chippawa Channel and Niagara River Channel www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov join at the northwest end of Grand Island. The boundary again follows a 888-990-NOAA general middle of the river course around the south side of Goat Island and over Niagara Falls. What are Nautical Charts? Chart Datum, Upper Niagara River.–Depths and vertical clearances under overhead cables and bridges in the Niagara River from its Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show confluence with Lake Erie to the head of navigation, the turning basin at water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Niagara Falls, NY, is as follows: from Lake Erie to the Black Rock Canal more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and Lock is the Low Water Datum of Lake Erie, 569.2 feet (173.5 meters); efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial from just below the Black Rock Canal Lock to the south end of Grand ships that carry America’s commerce. -

Ann Forsyth DESIGNING SMALL PARKS

Ann Forsyth DESIGNING SMALL PARKS DESIGNING SMALL PARKS r -. A Manual Addressing Social and Ecological Concerns B~ An-f1? Musacchi. With Frank I John Wiley & Sons, Inc. This book is printed on acid-free paper. @ Copyright O 2005 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada This project was supported by the USDA Forest Service Urban and Community Forestry Program on the recommendation of the National Urban and Community Forestry Advisory Council. Except where noted, all drawings are from the Metropolitan Design Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and used by permission. All photographs without additional credits are available in the Metropolitan Design Center's Image Bank at www.designcenter.umn.edu. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com1golpermission. Limit of LiabilitylDisclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

The Corporation of the City of Welland Official Plan

THE CORPORATIONOF THE CITY OF WELLAND Q,FFICIAL PLAN Revised: November 4, 2019 [this page is intentionally blank] AMENDMENT BY‐LAW BY‐LAW DATE APPROVAL PURPOSE NUMBER NUMBER DATE 1 2012‐64 February 25, 2013 OMB ORDER High Density Issue Date Residential Section February 25, 4.2.3.20.A (529 South 2013 Pelham Road 2 2013‐95 July 16, 2013 August 13, 2013 Low Density Residential Section 4.2.3.20.C 3 2013‐104 August 12, 2013 September 10, Medium Density 2013 Residential Section 4.2.3.20.D (Coyle Creek Estates Phase 6 Subdivision 4 2013‐110 August 27, 2013 September 26, Area 3: Canadian Tire 2016 Financial Site Section 6.7.3.1 to 6.7.3.4 (475, 55 and 635 Princes Charles Drive) Low Density Residential Section 4.2.2.2.B Parks, Open Space and Recreational Section 6.2.2.1.B Site Plan Control Section 7.8.1 (Various City‐owned Facilities) 5 2013‐118 September 10, October 10, 2013 High Density 2013 Residential Section 4.2.3.20.E (1 Griffith Street) 6 2014‐89 July 15, 2014 August 7, 2014 Community Commercial Corridor Section 4.4.3.13.B (152 Hellems Avenue and 131 Young Street) 7 2014‐138 October 7, 2014 November 11, Core Natural Heritage 2014 System, Open Space & Recreation, Low Density Residential, Medium Density Residential, Area Specific Low Density Residential and Area Specific Medium Density Residential Section 4.4.3.13.D (Sparrow Meadows Estates Subdivision) 8 2015‐58 May 19, 2015 File closed by Community OMB September Commercial Corridor 21, 2015 June Section 4.4.3.13.E (142 23, 2015 and 144A Thorold Road) 9 2015‐58 May 19, 2015 File closed by